Figure 40-1. Therapy continuum for cancer pain management. The first three steps are based on the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder and include a wide range of system analgesics (nonopioid, adjuvant, and opioid analgesics). The final step (“Beyond the WHO Ladder”) includes additional therapies for pain refractory to systemic analgesics.

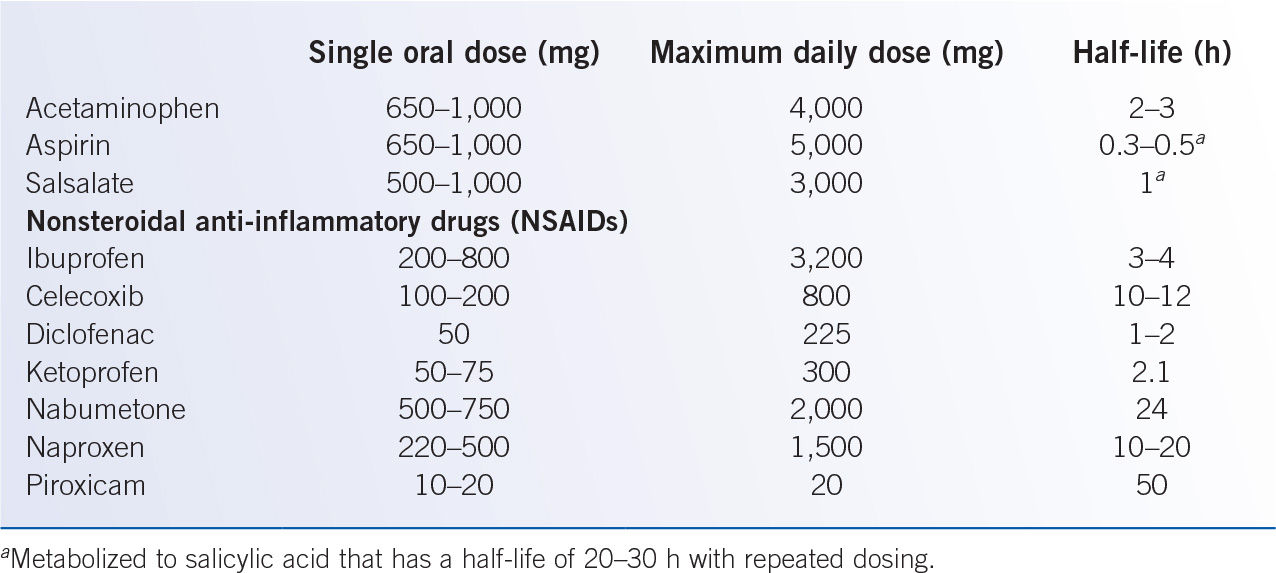

B. Nonopioid analgesics (Table 40-2) are the principal analgesics for mild pain. In more severe pain, nonopioids are used to supplement opioid to improve pain control and reduce opioid dose (to reduce opioid-related adverse effects and the risk of opioid tolerance).

1. Aspirin and the nonacetylated salicylates are modestly potent analgesics and antipyretics. Aspirin is a uniquely potent inhibitor of platelet function, but the nonacetylated salicylates have no impact on platelet function. The risk of gastrointestinal ulceration, somewhat greater with aspirin than other salicylates, significantly limits the analgesic utility of these agents, especially in medically ill or elderly patients. Salicylate is metabolized in the liver with renal excretion of salicylate and inactive metabolites.

2. Acetaminophen is a modestly potent but effective analgesic and antipyretic. Typical doses (650 to 1,000 mg QID, maximum 4,000 mg/day) are well tolerated, but excessive doses may cause severe hepatotoxicity; for added safety margin, consider limiting chronic acetaminophen dosing to 3,000 mg per day. Acetaminophen is available for intravenous, oral, and rectal administration, but intravenous formulation is expensive, and rectal absorption is poor.

C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are useful in pain from inflammatory processes and/or boney metastases. NSAIDs limit facilitation of pain signal transmission by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis in peripheral tissues and central nervous system (CNS). Renal toxicity, gastrointestinal ulceration, and platelet dysfunction limit NSAID utility, especially in medically ill patients. Selective cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors (celecoxib 200 mg daily or BID) have lower risk of gastrointestinal ulceration and no platelet dysfunction, but increased risk of thromboembolic events limits use. Although NSAIDs are administered orally, intravenous formulations (ketorolac (15 to 30 mg i.v./i.m., QID, maximum 5 days due to gastric ulceration risk) and ibuprofen (400 to 800 mg i.v. q 6 hours) are options when enteral administration is not feasible.

D. Opioid analgesics

1. General principles for the use of opioid analgesics

a. Use a comprehensive pain assessment to gather information to guide pain therapy. Repeat/review assessment at each patient contact and whenever pain is not controlled.

b. Teach patients and their families to assess pain by using a numeric score to facilitate communication. Documentation of pain intensity rating, the fifth vital sign, is standard for outpatient and inpatient care.

c. Administer analgesics orally or through the least invasive route that provides effective pain control.

d. Document all narcotic prescriptions in the medical record to aid in the monitoring and adjustment of pain therapy (and to comply with federal and state regulations).

e. Individualize opioid dose. The correct dose is that which adequately controls pain while minimizing adverse effects. Depending on pain severity, degree of opioid tolerance, and comorbid factors, the required daily dose of opioid can range over two to three orders of magnitude.

f. Avoid use of combination analgesic preparations, which contain opioid together with an NSAID or acetaminophen, unless that specific combination of medications is indicated for the specific patient; single agent formulations facilitate analgesic dose titration.

g. Anticipate opioid-related adverse effects and treat promptly (Table 40-3). Almost everyone taking opioid daily will need daily laxatives to prevent constipation.

h. Use regularly scheduled, long-acting analgesic preparations (extended-release preparations of morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone; fentanyl transdermal patch; and methadone) to improve compliance and provide more consistent pain relief than repeated as-needed dosing of short-acting opioid. Extended-release oral tablets should be swallowed whole and not cut or crushed.

i. Prescribe supplemental doses of opioid for “breakthrough pain” not controlled by the regularly scheduled doses. Use short-acting, immediate-release oral preparations of opioid (morphine, oxycodone, and hydromorphone) at doses of 10% to 15% of total daily opioid dose, as often as every 1 hour as needed.

j. Be flexible but aggressive in treating severe, uncontrolled pain. Hospital admission for parenteral opioids and frequent reassessment of analgesic efficacy may be required. In a pain emergency, opioid should be given intravenously (e.g., morphine 1 to 4 mg i.v., every 10 minutes) and titrated to effect. Once pain is improved, a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) device may facilitate access to, and documentation of, needed opioid for subsequent conversion to oral formulations.

Managing Common Opioid Side Effects |

Side effects | Comments and management |

|

Constipation | Most common side effect | Stool softeners (docusate) |

| No tolerance | Stimulants (senna and bisacodyl) |

| Use agents regularly and prophylactically | Bulk laxatives (psyllium) |

| Educate patients Combine agents | Osmotic agents (lactulose and polyethylene glycol) |

|

| Enemas |

|

| Opioid antagonist (oral naloxone and subcutaneous methylnaltrexone) |

Sedation | Avoid confounding medications | Dextroamphetamine |

| Lower opioid dose by 25% | Methylphenidate |

| Use stimulants | Modafinil |

| Opioid substitution | Donepezil |

| Add adjuvant to reduce opioid dose |

|

| Use neuraxial route of delivery |

|

Nausea and vomiting | Manage constipation | Promethazine |

| Treat with antiemetics | Prochlorperazine |

| Correct metabolic factors | Olanzapine |

| Switch to another opioid | Ondansetron and dolasetron |

| Tolerance develops slowly | Scopolamine |

|

| Hydroxyzine |

|

| Dexamethasone |

Myoclonus | Usually with high dosages | Lorazepam |

| Switch to another opioid | Clonazepam |

| Lower dose of opioid | Diazepam |

| Avoid meperidine |

|

Pruritus | Treat with antihistamines | Diphenhydramine |

| Consider a different opioid | Hydroxyzine |

|

| Ondansetron |

|

| Nalbuphine |

Withdrawal symptoms | Taper dose by half every other day when discontinuing | Clonidine |

Opioid Toxicity Syndrome (OTS) | Risk factors: rapidly increasing, high-dose opioid; dehydration; and renal failure Severe myoclonus may mimic seizures | Opioid rotation, adequate hydration, and opioid dose reduction |

Seizures rarely have been reported with high-dose opioid infusion, typically associated with preservative agents. If using high-dose infusion, use preservative-free opioid preparations.

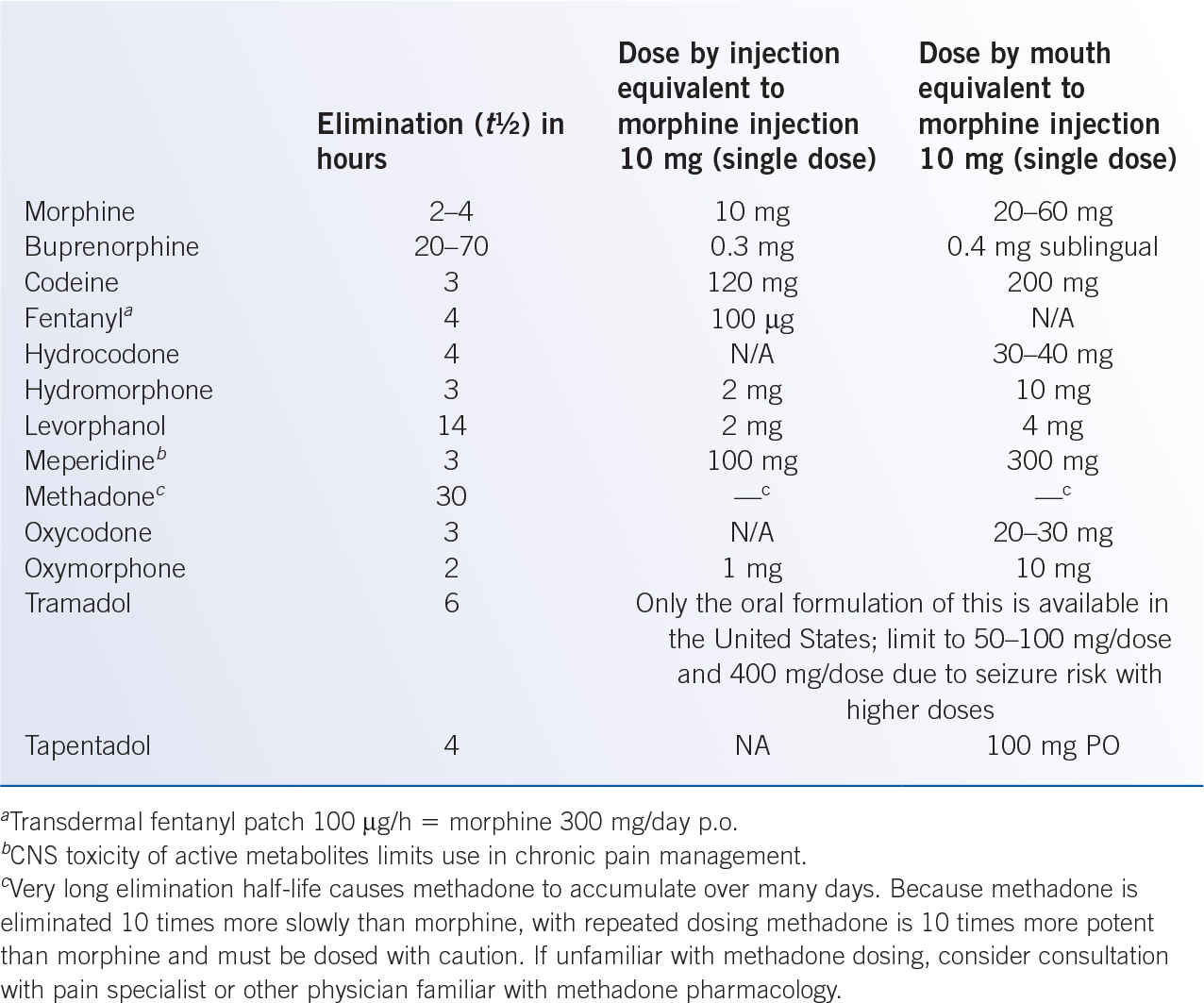

k. Be aware of equipotent doses of various opioid analgesics to facilitate changes between agents or routes of administration (Table 40-4).

l. Use naloxone to treat severe respiratory depression related to opioid overdose. About 0.1 to 0.2 mg i.v./i.m. every 1 to 5 minutes as needed; however, opioid antagonism with naloxone may cause extreme pain and other opioid withdrawal symptoms.

2. Limitations of opioid use in cancer pain management. Opioids are the principal analgesics for the management of moderate-to-severe cancer pain; however, several factors limit opioid utility, including adverse effects (Table 40-3), limited efficacy, and access-to-care issues (Table 40-1).

a. Common opioid adverse effects, especially constipation and nausea, should be anticipated so that management strategies can be implemented promptly (Table 40-3).

i. Respiratory depression—increased susceptibility with preexisting lung disease, sleep apnea, and cardiac disease; somewhat decreased susceptibility with chronic opioid exposure (tolerance). If significant respiratory depression or opioid-induced sedation develops, consider naloxone administration (0.1 to 0.2 mg i.v./i.m. every 1 to 5 minutes as needed); abrupt naloxone reversal of opioid effect may lead to acute opioid withdrawal syndrome (severe pain exacerbation, hypertension, tachycardia, dyspnea, pulmonary edema, and delirium).

ii. Sedation—typically managed with opioid dose titration, but severe or progressive sedation may signal pending respiratory depression/arrest and necessitate at least temporary opioid discontinuation or even reversal with naloxone. New onset sedation, with stable chronic opioid regimen, may suggest other contributing abnormality: decreased opioid clearance (hepatic and renal insufficiency), CNS pathology, and sepsis.

iii. Hypogonadism—common in chronic opioid therapy, especially higher dose morphine >100 mg daily, due to opioid suppression of hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. Symptoms, in men and women, may include impaired sexual function, decreased libido, infertility, depression, fatigue, and loss of muscle mass and strength. Opioid endocrine impact may be confounded by consequences of underlying malignancy and/or other medical conditions; management may include opioid titration/discontinuation and/or hormonal replacement therapy, if needed.

iv. Immunosuppression—opioid-induced immunosuppression is readily demonstrated in experimental animals, yet the clinical significance is confounded by comorbid disease pathophysiology and lack of randomized clinical trials.

v. Tolerance/hyperalgesia—essentially all patients receiving chronic opioid therapy develop opioid tolerance, sometimes managed with an increase in opioid dose. Increasingly, opioid tolerance is thought to reflect an induced hyperalgesic state in which chronic opioid still inhibits pain signal transmission, but increasingly facilitates pain signal transmission, resulting in more pain that is more resistant to management. Lack of randomized clinical trials limits clear separation of tolerance from other causes of hyperalgesia; however, people taking opioid chronically generally have significant hyperalgesia. Concern for opioid-induced hyperalgesia has resulted in a marked reduction of opioid use for chronic noncancer pain management and raises concern for chronic opioid use in long-term cancer survivors.

b. Opioid analgesic efficacy is best for moderately severe pain that is continuously present. Efficacy may be limited by the following:

i. Neuropathic pain, especially associated with severe sensitivity to light mechanical stimulation, may be relatively resistant to opioid analgesics, but may benefit from adjuvant analgesics (anticonvulsants and antidepressants).

ii. Episodically severe pain may represent a timing challenge for analgesic dosing. Pain episodes may be inadequately controlled while waiting for analgesic effect onset. Conversely, analgesics dosed to control very severe pain episodes may result in relative overdose when the pain episode subsides.

iii. Sharp somatic pain (e.g., wound debridement, pathologic bony fracture) is generally not adequately controlled with opioid except at doses associated with marked sedation. Sharp somatic pain may require “anesthetic” rather than “analgesic” management.

iv. Intractable pain, especially in advanced cancer, may not be adequately controlled despite optimal adjustment of systemic analgesics, and may require interventional pain therapies or other techniques.

3. Specific opioid analgesics (Table 40-4)

a. Morphine is hepatically metabolized to active metabolites that contribute to analgesic effect and toxicity. Morphine and metabolites undergo combined fecal and renal excretion; morphine should be used with caution in renal insufficiency as metabolites may accumulate and cause toxicity. Although oral administration is preferred for most patients, morphine can be administered through intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, sublingual, rectal, topical (for painful skin ulceration), epidural, and intrathecal routes.

b. Hydromorphone, and its active hepatic metabolites, are renally cleared by the kidneys and can accumulate in renal failure, precipitating opioid toxicity. In some individuals, common opioid adverse effects may be less with hydromorphone than with morphine. Hydromorphone can be administered through intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, sublingual, rectal, epidural, and intrathecal routes, although oral absorption is less reliable than with oxycodone or morphine.

c. Fentanyl

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree