Overview of Surgical Resection of Space Sarcomas

Amir Sternheim

Tamir Pritsch

BACKGROUND

The three main extracompartmental spaces of the lower extremities are the femoral triangle, the sartorial canal, and the popliteal space. Each of these spaces is confined by the bordering compartments of the lower extremity.

All extracompartmental spaces have walls comprising the muscles and their fascia of the neighboring compartment, lumen, that is filled with fat, fibrous tissue, and vessels that traverse the space, namely, arteries, veins, and nerves.

The distinction between intracompartmental and extracompartmental spaces was introduced by Enneking in his classification of soft tissue tumors as part of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) surgical staging system more than two decades ago. Enneking borrowed the term extracompartmental from his classification of bone tumors. In that context, it refers to tumors that originate in the bone and then breach the cortex and have a soft tissue component.

Extracompartmental tumors were considered to be more aggressive than their intracompartmental counterparts and therefore harder to treat and with a worse prognosis, although this has changed in recent years.

The original soft tissue sarcoma (MSTS) staging system had three prognostic criteria: metastasis, grade, and compartmentalization.

The term compartmentalization divides soft tissue sarcomas into intracompartmental and extracompartmental tumors. Intracompartmental lesions are bound in all directions by natural barriers such as bone and muscle. These tumors arise within a structure—thigh: anterior, adductor, posterior; leg: anterior, peroneal, posterior superficial, posterior deep.

In contrast, extracompartmental tumors either arise in spaces that are not bound by tight muscle fascia as compartments are (ie, popliteal space, sartorial canal, femoral triangle, axilla, antecubital fossa, paraspinal, intrapelvis, midhand, midfoot, and hindfoot) or develop secondary to the extension of an intracompartmental tumor beyond the confines of a compartment.

Extracompartmental tumors have unique characteristics. They can extend a considerable distance with less anatomic restraint. They frequently arise in close proximity to the neurovascular bundle. For these reasons, space tumors were initially considered to have a poorer prognosis than those confined to a compartment at diagnosis. Newer prognostic studies of soft tissue sarcomas do not support the assumption that space tumors have a worse prognosis due to their location but rather due to their size.

Space tumors have been poorly addressed in Enneking’s classification and in the later American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification. The classification of an intracompartmental lesion was based on tumor biology. Extracompartmental tumors were originally tumors that grew from within a compartment outward and into an adjacent compartment. Only later was the definition broadened to include space tumors. Since then, these space tumors have been poorly discussed in terms of their anatomy, biology, and surgical approach.

The newer version of the AJCC classification for the staging of soft tissue sarcomas does not use compartmentalization as a staging criteria but rather tumor grade, size, and depth.

Resection goals for soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities are wide resection of the lesion with negative resection margins and satisfactory extremity function.

With intracompartmental tumors, these goals are achieved by resecting the tumor with the muscle that surrounds it. Space tumors lie in proximity to vessels and nerves, so achieving wide resection of the tumor without resecting the vessels is a delicate task.

Some tumors, although in intimate proximity to the vessels, may still be resected with negative margins, whereas other tumors behave differently and invade the vessels. Vessel invasion dictates vascular resection. This biologic difference in tumor behavior is dictated by tumor grade, size, and biology.

Different tumors, due to their different biology, dictate different surgical resection techniques. Unlike intracompartmental tumors, space tumors differ vastly from one tumor to the next in the amount and technique of resection needed. Guidelines for resecting the different types of space tumors are lacking.

ANATOMY

Femoral Triangle Space

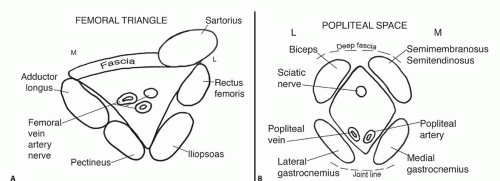

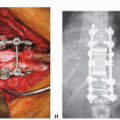

The femoral triangle can be depicted as a three-dimensional pyramid. The base is the inguinal ligament, bound laterally by the sartorius and medially by the medial edge of adductor longus or the anterior border of gracilis (FIG 1).

The floor of the femoral triangle is the iliopsoas laterally and the pectineus and adductor longus medially. Its apex is where the sartorius crosses over to the adductors.

The main vessels traversing the canal are, from medial to lateral, the femoral vein, artery, and nerve. They enter the femoral triangle from the abdomen under the inguinal ligament and exit it distally from the tip of the pyramid into the sartorial canal.

Sartorial Canal

The sartorial canal lies between the anterior (quadriceps) compartment and the medial adductor compartment, connecting the tip of the femoral triangle in the proximal thigh

to the popliteal fossa in the distal posterior aspect of the thigh. The cross-section of the sartorial canal is shaped like an inverted triangle (FIG 2).

The roof of the canal is made up of the sartorius muscle, which lies anterior and medial to the canal. The adductor longus makes up the floor of the canal. The lateral border is the thick fascia of the vastus medialis. Posteriorly, the border of the canal is the adductor compartment, namely, the adductor magnus.

Both the posterior and lateral borders are also covered with thick fascia. The superficial femoral artery and the femoral vein enter the canal proximally through the tip of the femoral triangle. These structures lie deep in the canal and are surrounded throughout their length by a very thick fascial sheath.

The vessels exit the canal at the distal-medial end through the adductor hiatus, a foramen in the distal part of the adductor magnus.

Popliteal Space

The popliteal space is shaped like a three-dimensional diamond. On its proximal-lateral side is the biceps femoris muscle. On the proximal-medial side are the semitendinosus and semimembranosus muscles. On the distal side of the space are the lateral and medial heads of the gastrocnemius muscles (see FIG 1B).

Anterior to the space is the posterior capsule of the knee joint. Posterior to the space is a thick popliteal fascia.

Vessels of the popliteal space are the popliteal artery and vein, which enter proximally through the adductor hiatus and exit distally between the two heads of the gastrocnemius.

The sciatic nerve enters the space through the proximal tip and divides into the peroneal and tibial nerve branches.

INDICATIONS

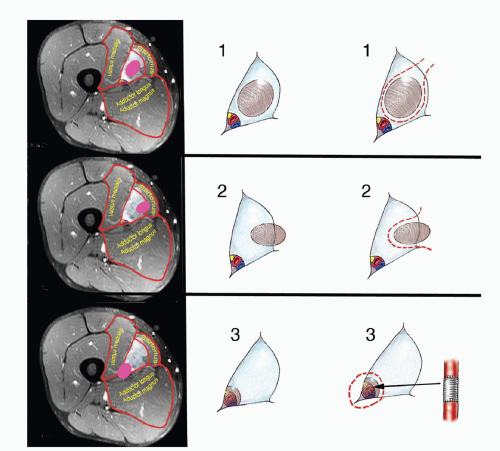

A set of surgical guidelines is a helpful clinical conceptual tool in resecting lower extremity soft tissue sarcomas from the three anatomic spaces. Using preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and initial intraoperative impressions, tumors may be divided into three groups.

Tumors are divided according to their location of origin.

Type 1 tumors arise from within the space. Typically, they originate from fat or fibrous tissue within the space. These tumors are termed luminal because they may approximate but do not adhere to the walls of the space or any of the arteries, veins, and nerves in the space. They lie within the lumen.

Type 2 tumors arise from one of the walls that border the space. These tumors arise from within a muscle or the muscle fascia that borders the space.

Type 3 tumors invade the arteries, veins, or nerves and are termed vessel lesions. These lesions either originate from or invade the vessels walls.

The surgical planes of resection differ for each of the three types:

Type 1 (luminal) lesions are resected with a thin cuff of healthy tissue that surrounds the tumor. At times, these tumors almost deliver themselves once the space is opened. Tumor margins, although negative, are often close.

Type 2 (wall) lesions are essentially resected with the muscle from which they originate. Wide surgical resection is achieved by resecting the tumor with its muscle of origin and the fascia covering that muscle.

Tumors that approximate the vessels and are adherent to the vessel sheath are resected with the vessel sheath as an oncologic barrier and should be approached in the following manner. On approaching the tumor area, if the sheath appears free and separates easily from the wall of the artery, the surgeon continues the dissection, leaving the

sheath attached to the surface of the specimen by making an incision in the sheath on the side away from the tumor and extricating the artery (and vein if possible) from its sheath.

The fibrous sheath surrounding the vessels is inspected carefully on frozen section after it has been removed en bloc with the tumor. Even when the tumor does not adhere to the vessel sheath, it should be removed separately from the tumor so that it can be examined to rule out tumor invasion through the sheath, thus ensuring safe resection margins.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree