Overview of Pelvic Resections: Surgical Considerations and Classifications

Ernest U. Conrad III

Vincent Ng

Jason Weisstein

Jennifer Lisle

Amir Sternheim

Martin M. Malawer

BACKGROUND

The pelvis is a relatively common anatomic location for metastatic and primary musculoskeletal tumors.

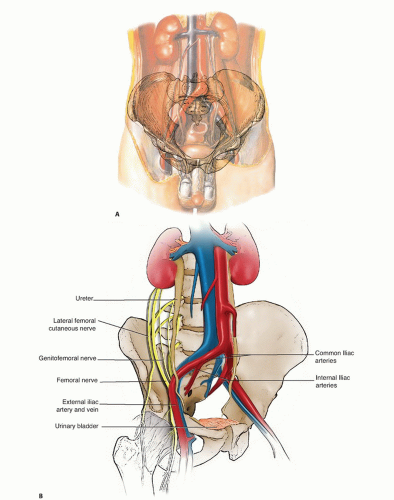

Surgical resection is more challenging in the pelvis than in other locations because of the complex anatomy and the proximity to vital abdominal viscera and major blood vessels and nerves. Making decisions about surgical resectability of a tumor involves the assessment of possible osseous or neurovascular involvement, in addition to the possible involvement of adjacent viscera (ie, bowel, ureter, and bladder). Therefore, preoperative evaluation and extensive imaging are critical. Osseous resection and reconstruction usually are carried out adjacent to major nerves, beneath the iliac vessels, or adjacent to the bladder or bowel.

Tumor surgery around the pelvis has the highest rate of complications, infections, and mechanical failure of all anatomic sites.

ANATOMY

Pelvic Nerves

Sciatic Nerve

The sciatic nerve arises from L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3. The nerve emerges from the pelvis through the greater sciatic notch inferior to the piriformis muscle and enters the thigh lateral to the ischial tuberosity. In 10% of patients, the sciatic nerve penetrates the substance of the piriformis muscle. The sciatic nerve is accompanied by the inferior gluteal artery.

It is essential to protect the sciatic nerve early in most procedures. Inside the pelvis, the nerve should be identified distally at the greater sciatic notch. Proximally, it should be picked up below the psoas muscle. The sciatic nerve is formed at the junction of the lumbar sacral plexus where these two trunks come together.

Great care must be taken, as the nerve exits the pelvis at the level of the greater sciatic notch, not to injure the accompanying inferior and superior gluteal nerves and arteries because these supply the abductors as well as the gluteus maximus muscle. The gluteus maximus muscle is essential for closure of most pelvic resections.

Femoral Nerve

The femoral nerve arises from posterior divisions of the ventral rami of L2 and L3 and passes inferolaterally between the psoas and iliacus muscles. It passes over the superficial iliacus muscle to enter the proximal thigh underneath the inguinal ligament, just lateral to the superficial femoral artery.

This nerve is almost always preserved during pelvic resections. It should be identified early during most procedures. The femoral nerve is identified in the space between the iliacus and psoas muscles as they exit the pelvis. The femoral nerve lies just below the fascia, bridging the interval between the two muscles, lateral to the femoral artery and vein.

Obturator Nerve

The obturator nerve, formed from the anterior branches of L2, L3, and L4, is the largest nerve formed from anterior divisions of the lumbar plexus. The nerve descends thru the iliopsoas muscle and courses distally over the sacral ala into the lesser pelvis, lying lateral to the ureter and under the internal iliac vessels. It then traverses the obturator foramen into the medial thigh, under the superior pubic ramus, dividing into anterior and posterior branches.

This nerve is routinely transected during pelvic floor resections (type III) due to its intimate proximity to the tumor.

Lumbar Plexus Sensory Nerves

The iliohypogastric (L1), ilioinguinal (L1), genitofemoral (L1, L2) and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves, which arises from L2 and L3, travel downward laterally along the iliopsoas muscle, pass underneath the lateral aspect of the inguinal ligament, and pass just distal and medial to the anterior superior iliac crest to innervate the anterolateral thigh.

This nerve is sacrificed during most pelvic surgical procedures.

Pelvic Vessels

Aortic Bifurcation

Descending the abdomen to the left of the vena cava, the aorta bifurcates at the level of L4 into common iliac vessels at the level of L4-L5. The common iliac bifurcates into internal and external iliacus vessels at the level of S1, the ala sacralis. The level of these bifurcations may vary, especially if the vessels are pushed by a large adjacent tumor mass (FIG 1A).

It is essential to identify two levels of bifurcations before any ligation: the aortic bifurcation and the common iliac bifurcation. Even the best surgeons have ligated the wrong vessels due to distorted anatomy. Such a misstep is especially possible with tumors that cross the midline. Preoperative evaluation with angiography is required for a comprehensive evaluation.

Common Iliac Artery

The common iliac artery must be identified early to correctly identify the aorta as well as the internal iliac (hypogastric)

artery (FIG 1B). To the surgeon, the major anatomic features of the common iliac artery are as follows:

No arterial branches arise from the artery (although the common iliac vein does have a major branch joining in, the iliolumbar vein).

The bifurcation of the common iliac artery into the external and internal iliac arteries is at the exact level at which the ureter crosses on the adjacent peritoneal surface. The ureter is routinely identified at this location early in the retroperitoneal dissection.

Failure to achieve vascular control of the common external or internal iliac artery or vein can result in uncontrolled blood loss as a consequence.

External Iliac Artery

The external iliac artery contributes to the inferior epigastric artery and extends distally, as the superficial femoral artery, into the femoral triangle, where it is a useful landmark in identifying neighboring structures.

Internal Iliac Artery

The internal iliac (hypogastric) artery descends from the lumbosacral articulation to the greater sciatic notch and branches into several arteries. The internal iliac artery and vein often are difficult to identify or ligate. The internal iliac artery lies on top of its vein, which often is large and is easily injured. The hypogastric vessels are routinely ligated in performing modified hemipelvectomies as well as many pelvic resections.

Anterior branches

The obturator artery exits the pelvis via the obturator canal (beneath the superior pubic ramus).

The inferior gluteal artery curves posteriorly between the first and second or second and third sacral nerves, then runs between the piriformis and coccygeus muscles or through the greater sciatic foramen into the gluteal region below the piriformis muscle.

Posterior branches

The iliolumbar artery ascends posterior to the obturator nerve and external iliac vessels to the medial border of the psoas. It then divides into the lumbar branch, to the psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles and to the spinal cord, and an iliac branch, to the iliac, gluteal, and abdominal musculature. The iliac branch often is ligated during surgery.

The superior gluteal artery runs posteriorly between the lumbosacral trunk and first sacral nerve and leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen superior and posterior to the piriformis muscle. Great care must be taken to preserve the gluteal vessels and nerves when performing types I and II pelvic resections.

Ureter

The ureter originates from the renal pelvis at the level of L1 and courses in the retroperitoneum to the medial surface of the psoas major muscle, crossed by spermatic or ovarian vessels.

The ureter crosses from lateral to medial on the surface of the peritoneum at the level of the common iliac bifurcation.

This is a good landmark to identify the ureter during the initial retroperitoneal dissection.

The ureter then courses medially at the level of the sciatic notch to insert into the trigone of the bladder.

Corona Mortis

The corona mortis is an anastomosis of the external iliac, inferior epigastric, and obturator vessels located in the retropubic region approximately 3 cm from the symphysis pubis. Laceration during an ilioinguinal approach can lead to extensive bleeding.

The retroperitoneal space between pubis and bladder is called the space of Retzius.

Inguinal Canal

The anatomic confines of the inguinal canal are described as 4 cm from the deep inguinal ring to the subcutaneous ring. This “deep ring” is the “direct” inguinal space originating lateral to the epigastric vessels. Hesselbach triangle is the “indirect” hernia space originating medial to the epigastric vessels.

The inguinal contents vary by gender:

In males, the spermatic cord contains the ductus deferens, testicular artery, pampiniform plexus, lymphatics, autonomic nerves, the ilioinguinal and genital branches of the genitofemoral nerve, the cremasteric artery and muscle, and the internal spermatic fascia.

In females, the inguinal contents include the round ligament and the ilioinguinal nerve.

The anterior inguinal wall is formed by the aponeurosis of the external oblique and internal oblique (lateral) muscles.

The posterior inguinal wall runs medial to lateral and is formed by the reflected inguinal ligament, the inguinal falx, and the transversalis fascia.

The superior or cephalic inguinal wall is formed by arched fibers of the internal oblique muscle and the transverse muscle of the abdomen.

The inferior or caudal inguinal wall is formed by the inguinal and lacunar ligaments.

Boundaries

The sciatic notch should be identified early in surgery, both internally and externally, to protect the sciatic nerve and gluteal pedicles.

The superior cephalad margin of the pelvis is defined by the ilium and the rim of the great sciatic notch.

The posterior margin of the pelvis is bounded by the piriformis muscle and the superior gluteal vessels and nerve. Posterior to the piriformis muscle, the internal pudendal vessels and nerve course medially off the sciatic nerve and the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve, anterior to the piriformis.

Inferior margin: The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments are released during types I and II pelvic resections.

INDICATIONS

Recurrent Benign Tumors

Major pelvic resections rarely are performed for benign bony tumors. Occasionally, following multiple recurrences or when tumors are limited to either the superior or inferior pubic rami, pelvic resection is indicated.

Such benign tumors include large solitary osteochondromas or any osteochondroma associated with multiple hereditary exostosis due to the high risk of secondary chondrosarcoma.

Osteoblastoma occurring in the ilium or periacetabulum

Giant cell tumors or aneurysmal bone cysts have a predilection for the superior pubic ramus and supra-acetabulum.

Primary Malignant Osseous Tumors

Osteosarcoma

Five percent of all osteosarcomas occur in the pelvis. Partial pelvic resection or hemipelvectomy (amputation) is required, usually following induction chemotherapy.

Ewing sarcoma

About 25% of all Ewing sarcomas occur in the pelvis. Surgical resection is required.

Adjuvant radiation therapy is recommended in treating pelvic Ewing sarcoma with surgical resection.

Resection should be performed only following induction chemotherapy.

Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcomas are the most common primary malignant bony tumors of the pelvis.

They often are much larger than plain radiographs indicate. Further imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates the cartilaginous component of the tumor.

Metastatic Adenocarcinoma: Breast, Prostate, Renal, Lung, Colon

Metastatic adenocarcinoma most commonly involves iliac or periacetabular sites. Most metastatic tumors to the pelvis are treated adequately with radiation therapy.

Occasionally, there may be significant acetabular destruction with an impending pathologic fracture that requires surgical reconstruction.

Renal cell carcinoma (hypernephroma) metastases are an exception. These metastases often require surgical removal, either by resection or by curettage and cryosurgery. Preoperative embolization always is required for these vascular tumors to avoid severe bleeding during surgery.

Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas are more common than intraperitoneal sarcomas and must be evaluated carefully; preoperatively for gastrointestinal, genitourinary, vascular, or peripheral nerve involvement.

IMAGING AND OTHER STAGING STUDIES

Plain Radiography

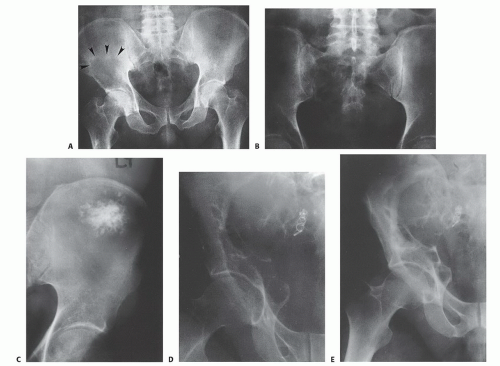

Plain radiography (FIG 2) is of limited value in the assessment of pelvic girdle lesions. Images often are obscure and confusing.

The pelvis, particularly the sacrum, is a difficult structure in which to recognize early bone lesions, and major bone lesions initially may be overlooked. For these reasons, there should be a low threshold for performing further imaging, especially for initial screening and the postoperative evaluation of reconstructions.

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

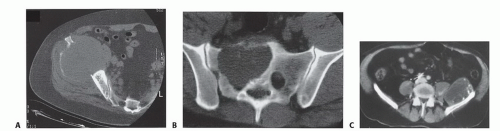

As a general rule, both computed tomography (CT) and MRI are well indicated for the initial evaluation of most pelvic tumors.

CT with intravenous contrast and three-dimensional reconstruction is the optimal technique for assessing the extent of bone involvement and destruction, the osseous anatomy, and the relation between the tumor and the major blood vessels of the pelvis (FIG 3). It is valuable for depicting any distortion of the pelvic anatomy and aiding in the evaluation of the tumor to decide whether it is resectable. Chest CT is essential for staging purposes in evaluation for pulmonary metastases.

MRI with contrast is critical for imaging soft tissue (ie, vessels, nerve, muscle) and osseous involvement. MRI is the optimal modality for imaging soft tissue and marrow involvement. It is attractive for assessment of osseous disease and sacral involvement and may be helpful with the serial assessment of neoadjuvant (induction) therapy.

Bone Scanning

Three-phase bone scan is used to rule out systemic metastasis and to assess the focal osseous involvement and tumor vascularity in the initial flow phase. A decrease in vascularity after induction chemotherapy may indicate response to treatment.

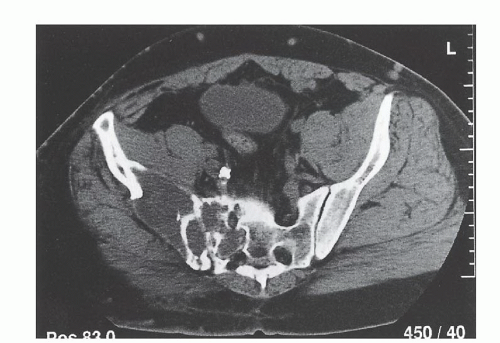

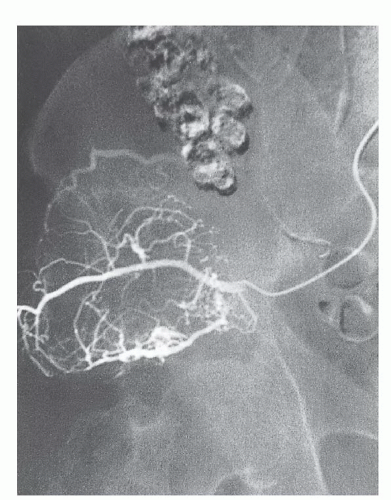

Angiography

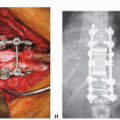

Angiography is mandatory for determining the distal vascular anatomy that often is distorted by large pelvic tumors (FIG 4). It is essential to determine the level of the various bifurcations preoperatively and to rule out vascular involvement by the tumor. Embolization of the tumor blood supply before surgery is helpful in minimizing blood loss, especially with vascular tumors and tumors with sacral involvement.

Venography

The pelvic veins always are much larger than their arterial counterparts. Preoperative venography is used to rule out tumor (mural) thrombi, a common finding in chondrosarcomas and osteosarcomas. Their presence may change the planned surgical approach. Postoperative venous Doppler is recommended routinely in all postoperative pelvic resection patients.

Fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose-Positron Emission Tomography

Fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) may be useful in assessing the “grade” of malignancy, evaluating response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and monitoring for local recurrence. Positron emission tomography (PET) combined with CT or MRI is useful for evaluating tumor response. PET-CT scans are useful in early detection of small recurrences. It plays only a minimal role in preoperative planning in determining the extent of surgical resection.

Biopsy

The purpose of biopsy is to yield a valid tumor diagnosis (benign vs. malignant), tumor grade (high vs. low grade), and tumor subtype (eg, leiomyosarcoma vs. malignant fibrous histiocytoma).

Biopsies may be performed by either open or needle technique.

Because open biopsy for pelvic tumors is an extensive procedure, needle biopsy—especially CT-guided needle biopsy—is recommended initially for both metastatic and primary pelvic tumors.

FIG 4 • Preoperative angiography and embolization of the metastatic lesion shown in FIG 3A. (Courtesy of Martin M. Malawer.)

Biopsy technique should follow established guidelines for incision placement within the line of eventual resection, minimize contamination of normal tissues (eg, achieve adequate hemostasis at biopsy closure), and retrieve an adequate specimen for frozen section diagnosis. The biopsy should avoid the gluteal and groin areas because they are potential sources for flaps for skin closure after anterior and posterior hemipelvectomy, if necessary.

The biopsy incision can also be placed transversely, in the line of the iliac or inguinal incision.

Anatomic Considerations

Evaluation of the full anatomic extent of a pelvic tumor cannot be based on a single imaging modality. Combined data, gained from two or more imaging modalities, allow a realistic appreciation of the exact anatomic extent. Even when that information is available, however, the full extent of a pelvic tumor often is underestimated preoperatively.

Review of any imaging study of the pelvis, because of the numerous anatomic details, must be performed very methodically. The authors review the structures from the back (midsacral region) and follow the pelvic girdle to the front (symphysis pubis), as described in the following paragraphs.

Sacrum, Sacral Alae, and Sacroiliac Joint

Most patients who undergo extended hemipelvectomy, which necessitates transection of the sacrum through the ipsilateral neural foramina, regain function of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. Adding a contralateral compromise of the sacral nerve root will create a severe dysfunction. Tumors that penetrate the sacrum and cross the midline are considered unresectable because of the involvement of bilateral sacral nerve roots (FIG 5). The tumor can be resected but the morbidity of bilateral sacral nerve root loss usually outweighs the questionable oncologic benefit from surgery.

The common iliac vessels are just anterior to the sacral ala, and any cortical breakthrough by a tumor in that site may be expected to extend directly to the blood vessels. The sacroiliac (SI) joint is a key anatomic landmark. The major nerves and blood vessels are medial to it; therefore, any tumor or pelvic resection lateral to the SI joint may be expected not to violate the major neurovascular bundle. Tumor transgression through the SI joint should be documented prior to surgery by using the combination of CT, MRI, and bone scan.

Major Pelvic Blood Vessels and Structures

The common iliac artery bifurcates along the sacral ala, and the ureter crosses the bifurcation on its ventral side. Large tumors around the sacral ala commonly displace and occasionally invade these structures. The mere presence of major blood vessel or pelvic viscus involvement by tumor is not an indicator of unresectability and demands preoperative planning. If necessary and curative resection is planned, both structures can be excised en bloc with the tumor and then can be repaired with a graft. However, when a complex resection (bony pelvis and viscus resection) is anticipated, the patient must be informed, and surgical assistance and necessary equipment must be prepared in advance.

Sacral Plexus

Current MRI imaging techniques cannot accurately identify nerve involvement by tumor.

Clinical evidence of femoral, sacral, or sciatic nerve dysfunction usually suggests direct tumor involvement. In most cases, the presence and extent of nerve involvement is established only at the time of surgery.

Sacral plexus invasion by tumor has the same significance in terms of resectability as tumor invasion of the sacrum; bilateral involvement is an indicator of probable unresectability.

Sciatic Notch and Nerve

The sciatic notch is the site of pelvic osteotomy in resections of the ilium or periacetabular region and in modified hemipelvectomy. CT establishes tumor extension to the sciatic notch, a tight space through which the sciatic nerve and superior gluteal vessels and nerve pass (FIG 6).

The piriformis muscle, which divides the sciatic notch, is a key structure because the sciatic nerve exits the pelvis underneath it and the superior gluteal artery exits the pelvis above it. The patency of the superior and inferior gluteal arteries, which supply the gluteal vasculature, is established by angiography.

Adequate blood supply of the gluteal region is a major preoperative consideration in flap design, and the artery must be

preserved in any pelvic resection, if oncologically feasible. The artery is located only a few millimeters from the periosteum of the sciatic notch roof, and it should be dissected carefully.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree