An understanding of the basic biology and pathology of bone and soft tissue tumors is essential for appropriate planning of their treatment.

This chapter reviews the unique biologic behavior of soft tissue and bone sarcomas, which provides the basis for their staging and resection and the use of appropriate adjuvant treatment modalities.

A detailed description of the clinical, radiographic, and pathologic characteristics for the most common sarcomas is presented.

Soft tissue and bone sarcomas are a rare and heterogeneous group of tumors. These neoplasms represent less than 0.2% of all adult and 15% of pediatric malignancies.

As of 2013, the annual incidence in the United States, which remains relatively constant, is approximately 11,400 soft tissue sarcomas (STS) and 3010 new bone sarcomas.1 About 4390 deaths from STS and 1440 deaths from bone cancers are expected in 2013.

In adults, over 40% of primary bone cancers are chondrosarcomas.

This is followed by osteosarcomas (OSs) (28%), chordomas (10%), Ewing tumors (8%), and malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH)/fibrosarcomas (4%). The remainder of cases are several rare types of bone cancers.

In children and teenagers (those younger than 20 years), OS (56%) and Ewing tumors (34%) are much more common than chondrosarcoma (6%).

In the United States, the 5-year survival rates for all bone sarcomas is about 70%. OS and Ewing sarcoma were comparable among 15 to 29 years old, about 60% for the most recent era. The U.S. bone cancer mortality was highest for males and females 15 to 19 years of age.

The 5-year survival rates for localized STS is 83% in 2013. This drops to 16% for systemic disease.2

Risk factors for soft tissue and bone sarcomas include previous radiation therapy, exposure to chemicals (eg, vinyl chloride, arsenic); immunodeficiency; prior injury (scars, burns); chronic tissue irritation (foreign body implants, lymphedema, chronic infection); neurofibromatosis; Paget disease; bone infarcts; and genetic cancer syndromes (eg, hereditary retinoblastoma, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Gardner syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, Werner syndrome, Bloom syndrome), Maffucci syndrome, Ollier disease, multiple osteochondromatosis, and hereditary multiple exostoses. In most patients, however, no specific etiology can be identified.

Sarcomas originate primarily from elements of the mesodermal embryonic layer.

STS are classified according to the adult tissue that they resemble.

Bone sarcomas usually are classified according to the type of matrix production: Osteoid-producing sarcomas are classified as OSs, and chondroid-producing sarcomas are classified as chondrosarcomas.

Tumors arising in bone and soft tissues have characteristic patterns of biologic behavior because of their common mesenchymal origin and anatomic environment. Those unique patterns form the basis of the staging system and current treatment strategies.

Histologically, sarcomas are graded as low, intermediate, or high grade. The grade is based on tumor morphology, extent of pleomorphism, atypia, mitosis, matrix production, and necrosis, with the two main factors being mitotic count and spontaneous tumor necrosis.

Tumor grade represents the tumor’s biologic aggressiveness and correlates with the likelihood of metastases. Low-grade lesions rarely metastasize. High-grade lesions metastasize in over 20% of patients.

Sarcomas form a solid mass that grows centrifugally, with the periphery of the lesion being the least mature.

In contradistinction to the true capsule that surrounds benign lesions, which is composed of compressed normal cells, sarcomas usually are enclosed by a reactive zone or pseudocapsule. This pseudocapsule consists of compressed tumor cells and a fibrovascular zone of reactive tissue with a variable inflammatory component that interacts with the surrounding normal tissues.

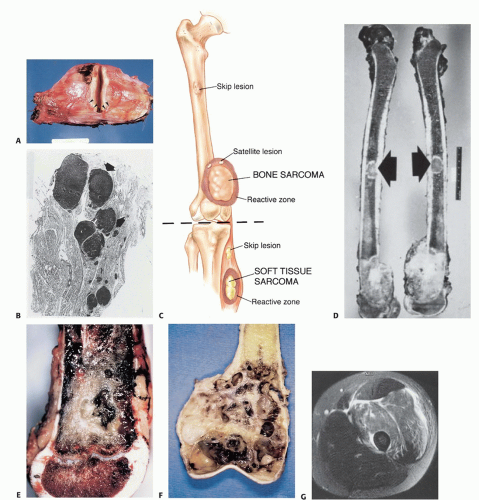

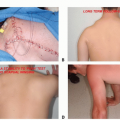

The thickness of the reactive zone varies according to the histogenic type and grade of malignancy. High-grade sarcomas have a poorly defined reactive zone that may be locally invaded by the tumor (FIG 1A).

Tumor foci within the reactive zone are called satellite lesions.

High grade, and occasionally low grade, may break through the pseudocapsule to form metastases, termed skip metastases, within the same anatomic compartment in which the lesion is located. By definition, these are locoregional micrometastases that have not passed through the circulation (FIG 1B).

This phenomenon may be responsible for local recurrences that develop in spite of apparently negative margins after a resection.

Although low-grade sarcomas regularly interdigitate into the reactive zone, they rarely form tumor skip nodules beyond that area (FIG 1C,D).

Sarcomas respect anatomic borders. Local anatomy influences tumor growth by setting natural barriers to extension. In general, sarcomas take the path of least resistance and initially grow within the anatomic compartment in which they arose. It is only at a later stage that the walls of the compartment are violated (either the cortex of a bone or aponeurosis of a muscle), at which time, the tumor breaks into a surrounding compartment.

Typical anatomic barriers are articular cartilage, cortical bone, and fascial borders. The growth plate is not considered an anatomic barrier because it has numerous vascular channels that run through it to the epiphysis (FIG 1E-G).

Sarcomas are defined as intracompartmental if they are encased within an anatomic compartment.

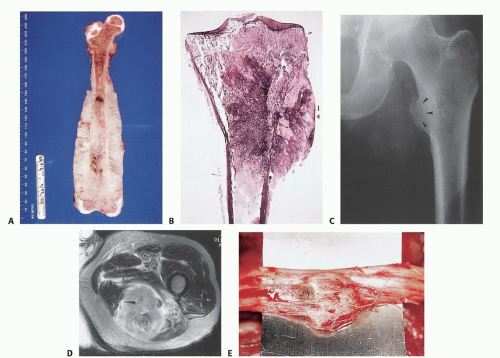

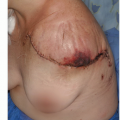

Extracompartmental tumors are those that grow out through the compartment barrier or tumors that have arisen in extracompartmental spaces (space tumors), that is, popliteal fossa, groin, sartorial canal, axilla, and antecubital fossa (FIG 2A,B).

Most bone sarcomas are bicompartmental at the time of presentation; they destroy the overlying cortex and extend directly into the adjacent soft tissues through the Haversian system and Volkmann canals of the cortical bone.

Carcinomas, which typically present in the extremities as metastatic disease, directly invade the surrounding tissues, irrespective of compartmental borders (FIG 2C-E).

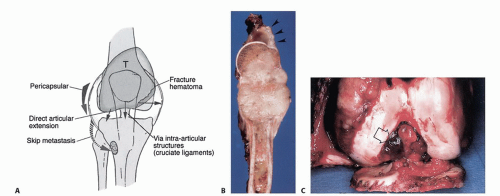

Joint involvement in sarcoma is uncommon because direct tumor extension through the articular cartilage is rare. Mechanisms of joint involvement in sarcoma are as follows:

Pathologic fracture with seeding of the joint cavity

Pericapsular extension

Structures that pass through the joint (eg, the cruciate ligaments) may act as a conduit for tumor growth (FIG 3).

Transcapsular skip nodules: demonstrated in 1% of all OSs

Direct articular extension

Unlike carcinomas, bone and STS disseminate almost exclusively through the blood. Hematogenous spread of extremity sarcomas is commonly manifested by pulmonary involvement and less commonly by bony involvement. Abdominal and pelvic STS, on the other hand, typically metastasize to the liver and lungs.

Low-grade STS have a low (under 15%) rate of subsequent metastasis, whereas high-grade lesions have a significantly higher (over 20%) rate of metastasis.

Metastases from sarcomas to regional lymph nodes are uncommon; the condition is observed in only 13% of patients with STS and 7% of those with bone sarcomas at initial presentation. The prognosis is somewhat better than to that of distant metastasis (FIG 4).

Most patients with high-grade primary bone sarcomas, unlike STS, have distant micrometastases at presentation; an estimated 80% of patients with OS have micrometastatic lung disease at the time of diagnosis. For this reason, in most cases, cure of a high-grade primary bone sarcoma can be achieved only with systemic chemotherapy and surgery.

As mentioned, high-grade STS have a lower metastatic potential. Because of that difference in metastatic capability, the role of chemotherapy in the treatment of STS and its impact on survival are still matters of some controversy.

Prognostic factors for bone sarcomas include grade, size, extension of tumor beyond the bone cortex, regional and metastatic disease, and response of the tumor to chemotherapy (necrosis rate).

Prognostic factors for STS include grade, tumor size, depth, age, margin status, location (proximal vs. distal), histologic subtypes, and metastatic disease.

Staging is the process of classifying a tumor, especially a malignant tumor, with respect to its degree of differentiation, as well its local and distant extent, to plan the treatment and estimate the prognosis. Staging of a musculoskeletal tumor is based on the findings of the physical examination and the results of imaging studies. Biopsy and histopathologic evaluation are essential components of staging but should always be the final step. An important variable in any staging system for musculoskeletal tumors, unlike a staging system for carcinomas, is the grade of the tumor.

The system most commonly used for the staging of STS is the one developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (Table 1).3 It is based primarily on the Memorial Sloan Kettering staging system and does not apply to rhabdomyosarcoma. Critics of this system point out that it is based largely on single-institution studies that were not subjected to multi-institutional tests of validity. The Musculoskeletal Tumor Society adopted staging systems that originally were described by Enneking et al4,5,6 for malignant soft tissue and bone tumors (Table 2), and the American Joint Committee

on Cancer developed, with a few changes, a staging system for malignant bone tumors (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 1 System of the American Joint Committee on Cancer for the Staging of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Primary Tumor (T)

TX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

T1

Tumor ≤5 cm in greatest dimension

(Size should be regarded as a continuous variable, and the measurement should be provided)

T1a

Superficial tumora

T1b

Deep tumora

T2

Tumor >5 cm in greatest dimensiona

T2a

Superficial tumora

T2b

Deep tumor

Regional Lymph Nodes (N)

NX

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0

No regional lymph node metastasis

N1b

Regional lymph node metastasis

Distant Metastasis (M)

M0

No distant metastasis

M1

Distant metastasis

Anatomic Stage/Prognostic Groups

Stage IA

T1a

N0

M0

G1, GX

T1b

N0

M0

G1, GX

Stage IB

T2a

N0

M0

G1, GX

T2b

N0

M0

G1, GX

Stage IIA

T1a

N0

M0

G2, G3

T1b

N0

M0

G2, G3

Stage IIB

T2a

N0

M0

G2

T2b

N0

M0

G2

Stage III

T2a, T2b

N0

M0

G3

Any T

N1

M0

Any G

Stage IV

Any T

Any N

M1

Any G

a Superficial tumor is located exclusively above the superficial fascia without invasion of the fascia; deep tumor is located either exclusively beneath the superficial fascia, superficial to the fascia with invasion of or through the fascia, or both superficial yet beneath the fascia.

b Presence of positive nodes (N1) in M0 tumors is considered stage III.

Reprinted with permission from American Joint Committee on Cancer. Soft tissue sarcoma. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, ed 7. New York: Springer, 2010:291-298.

Table 2 System of Enneking et al for Staging of Bone Sarcomas

Stage

Grade

Sitea

Metastasis

IA

Low grade

T1—intracompartmental

M0 (none)

IB

Low grade

T2—extracompartmental

M0 (none)

IIA

High grade

T1—intracompartmental

M0 (none)

IIB

High grade

T2—extracompartmental

M0 (none)

III

Metastatic

T1—intracompartmental

M1 (regional or distant)

III

Metastatic

T2—extracompartmental

M1 (regional or distant)

a Intracompartmental, bone tumors are confined within the cortex of the bone; extracompartmental, bone tumors extend beyond the bone cortex.

From Enneking WF. A system of staging musculoskeletal neoplasms. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;(204):9-24.

Table 3 System of the American Joint Committee on Cancer for the Staging of Bone Sarcomas

Stage

Tumor Grade

Tumor Size

IA

Low

<8 cm

IB

Low

>8 cm

IIA

High

<8 cm

IIB

High

>8 cm

III

Any tumor grade, skip metastasesa

IV

Any tumor grade, any tumor size, distant metastases

a Skip metastases: discontinuous tumors in the primary bone site.

Reprinted with permission from American Joint Committee on Cancer. Bone. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, ed 7. New York: Springer, 2010:281-290.

Enneking’s classical staging system is based on three factors: histologic grade (G), site (T), and the presence or absence of metastases (M). The anatomic site (T) may be either intracompartmental (A) or extracompartmental (B). This information is obtained preoperatively on the basis of the data gained from the various imaging modalities. A tumor is classified as intracompartmental if it is bounded by natural barriers to extension, such as bone, fascia, synovial tissue, periosteum, or cartilage. An extracompartmental tumor may be either a tumor that has violated the borders of the compartment from which it originated, or a tumor that has originated and remained in the extracompartmental space. A tumor is assigned to stage III (M1) if a metastasis is present at a distant site or in a regional lymph node.

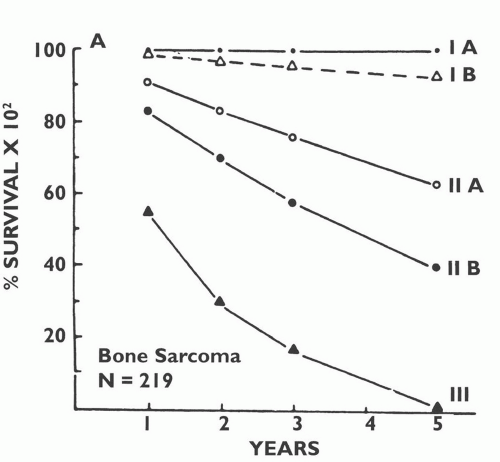

Enneking’s classification system is based on clinical data from an era in which chemotherapy was not given preoperatively and compartmental resections were much more common. Therefore, there was a clear correlation between the extent of the tumor at presentation, its relation to the boundaries of the compartment in which it is located, and the extent of surgery. A close correlation also was found between surgical stage of bone sarcoma and patient survival (FIG 5). Since that time, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to decrease tumor size and facilitate limb-sparing surgery as well as reduce the local recurrence rate. As a result, compartmental resections have become rare. Nonetheless, Enneking’s classification is based on the biologic behavior of soft tissue and bone sarcomas, and its underlying concept is as relevant today as it was in the early 1980s (see Tables 1,2,3 and 4).

Table 4 Enneking’s System for the Staging of Benign Bone Tumors

Typical Example

Stage

Definition

Biologic Behavior

Soft Tissue Tumor

Bone Tumor

1

Latent

Remains static or heals spontaneously

Lipoma

Nonossifying fibroma

2

Active

Progressive growth, limited by natural barriers

Angiolipoma

Aneurysmal bone cyst

3

Aggressive

Progressive growth, invasive, not limited by natural barriers

Aggressive fibromatosis

Giant cell tumor

From Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA. A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1980;153:106-120.

FIG 5 • Survival by Enneking’s surgical stage of 219 patients with primary bone sarcoma. (Courtesy of Martin M. Malawer.)

Approximate survival rates by stage for extremity STS are 90% for stage I, 70% for stage II, and 50% for stage III.

Enneking also described a staging system for benign bone tumors, which remains the one that is most commonly used (see Table 4). That system is based on the biologic behavior of these tumors as suggested by their clinical manifestation and radiologic findings. Benign bone tumors grow in a centrifugal fashion, as do their malignant counterparts, and a rim of reactive bone typically is formed as a response of the host bone to the tumor. The extent of that reactive rim reflects the rate at which the tumor is growing: It usually is thick and well-defined around slowly growing tumors and barely detectable around fast-growing, aggressive tumors.

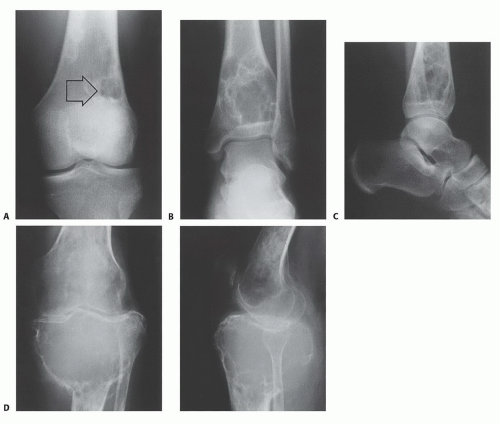

Latent benign bone tumors are classified as stage 1. Such tumors usually are asymptomatic and commonly are discovered as an incidental radiographic finding. Their natural history is

of slow growth, and in most cases, they heal spontaneously. These lesions never become malignant and usually heal following simple curettage. Examples include fibrous cortical defects and nonossifying fibromas (NOF) (FIG 6A).

Active benign bone tumors are classified as stage 2 lesions. These tumors grow progressively but do not violate natural barriers. Associated symptoms may occur. Curettage and burr drilling are curative in most cases (FIG 6B-E).

Aggressive benign bone tumors (stage 3) may cause destruction of surrounding bone and usually break through the cortex into the surrounding soft tissues. Local control can be achieved only by curettage and meticulous burr drilling with a local adjuvant such as liquid nitrogen, argon beam laser, or phenol. Wide resection of the lesion with a margin of normal tissue (FIG 6D,E) is another option.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree