Pure stromal tumors

Fibroma

Cellular fibroma

Thecoma

Luteinized thecoma associated with sclerosing peritonitis

Fibrosarcoma

Sclerosing stromal tumor

Signet-ring stromal tumor

Microcystic stromal tumor

Leydig cell tumor

Steroid cell tumor

Steroid cell tumor, malignant

Pure sex cord tumors

Adult granulosa cell tumor

Juvenile granulosa cell tumor

Sertoli cell tumor

Sex cord tumor with annular tubules

Mixed sex cord–stromal tumors

Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors

Well differentiated

Moderately differentiated with heterologous elements

Poorly differentiated with heterologous elements

Retiform with heterologous elements

Sex cord-stromal tumors, not otherwise specified

Granulosa cell tumors (GCTs) account for approximately 70 % of malignant SCSTs; adult granulosa cell tumors (AGCTs) are the most frequent (95 % of GCTs), and they occur more often in postmenopausal than premenopausal women, with a peak incidence between 50 and 55 years.

Juvenile granulosa cell tumors (JGCTs) were described the first time by Young in 1984, and they account for approximately 5 % of all GCTs. They have a natural history and histologic characteristics very different from the typical GCTs; approximately 90 % of JGCTs occur in prepubertal girls. In Young et al. series of 125 cases, 44 % of the tumors occurred before age of 10 years and only 3 % after the third decade of life [3, 4].

Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors or androblastomas (SLCTs) occur most frequently in the second and third decades, with 75 % of the lesions seen in women younger than 40 years. These neoplasms are extremely rare, accounting for less than 0.2 % of ovarian cancers [5].

Etiopathogenesis

Granulosa and Sertoli cells arise from the sex cords of the developing gonads, which originate from celomic epithelium. Granulosa cells derive from the cortical sex cord, while the Sertoli cells originate from medullary cords of mesonephric origin.

Very little is known about the etiology of SCSTs; one theory is that the degeneration of follicular granulosa cells after oocyte loss and the consequent compensatory rise in pituitary gonadotropins may induce an irregular proliferation. This hypothesis could be applied with the oocyte depletion and high levels of gonadotropins observed in menopausal patients; however, this explanation is not applicable to those tumors developing in young women.

A more recent hypothesis points toward the involvement of granulosa stem cells supported by the evidence of their ability to express telomerase [6].

However the most relevant discovery related to the etiopathogenesis of AGCTs is the finding of a somatic 402C > G missense point mutation in the gene encoding the FOXL2 (forkhead box L2). This finding is frequent, and more than 95 % of ovarian AGCTs harbor this type of mutation. FOXL2 somatic mutations may be involved in the tumorigenesis of these tumors due to a partial loss of function in its ability to induce apoptosis [7]. Moreover, Cheng et al. showed that the mutated form of FOXL2 may lead to the development of AGCT by reducing the expression of GnRH receptors, conferring resistance to GnRH-induced apoptotic effect [8].

These insights could have a clinical impact in developing targeted therapeutic strategies for AGCT patients.

FOXL2 shows a molecular interaction with others genes involved in the etiopathogenesis of AGCT such as SMAD3, CCND2, and GATA4 [9]. The clinical implications of these knowledges include the use of FOXL2 in the differential diagnosis of AGCT with an excellent specificity, considering that up to now there are no reports of any other tumor types being positive for this mutation [10].

FOXL2 has also clinical implication in the prognosis of AGCTs: patients with higher FOXL2 protein expression had worse overall survival and disease-free survival than those with negative or weak expression [11].

Chang et al. demonstrated that another molecule involved in the tumorigenesis of AGCT is activin A [12].

The other major recent finding regarding SCSTs is the mutation of DICER1; Schultz et al. reported that children with both pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) and SLCTs had germ line DICER1 mutations. They found these germinal mutations among family members of these patients [13]. Somatic DICER1 mutations are also described in SLCTs [14].

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, hamartomatous polyposis, and predisposition to benign and malignant tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, breast, ovary, uterine cervix, and testis. Germ line-inactivating mutations in 1 allele of the STK11/LKB1 gene at chromosome 19p13.3 have been found in most PJS patients. Although ovarian sex cord tumors with annular tubules (SCTATs) are very rare in the general population, they occur with increased frequency in women with PJS. Germ line mutations in the STK11 gene, accompanied by loss of heterozygosity were found in PJS-associated SCTATs [15].

Histopathology

SCSTs develop from the dividing cell population surrounding the oocytes, including the cells that produce ovarian hormones (the non-germ cell and non-epithelial components of the gonads), and therefore they vary in their capacity to produce clinically significant amounts of steroid hormones.

They are usually expressed at least one of the following markers (inhibin, calretinin, and FOXL2), but in 15 % of them, FOXL2 is the unique marker of sex cord differentiation.

AGCTs

Gross Findings

AGCTs vary from tiny lesions to huge masses with a mean diameter of about 13 cm. AGCTs are bilateral in only 2 % of cases. The external surface may be smooth or bosselated. The cut surface is often solid and sometimes partly solid and partly cystic. Hemorrhage and necrosis are common [16].

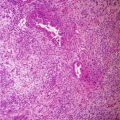

Microscopic Findings

The tumor cells grow in a variety of patterns, including microfollicular, macrofollicular, trabecular, insular, tubular, diffuse, moiré silk, and gyriform. The microfollicular variant, the most easily recognized, is characterized by multiple small rounded spaces formed by cystic degeneration in small aggregates of granulosa cells, containing eosinophilic PAS-positive material and often fragments of nuclear debris or pyknotic nuclei. These spaces, known as Call–Exner bodies, are found in only 30–50 % of tumors [17].

JGCTs

Gross Findings

JGCTs’ appearance is similar to the adult variant.

Microscopic Findings

JGCT is typically a solid cellular neoplasm, with focal follicle formation. The follicles are of variable sizes and shapes but generally don’t reach the large size of the follicles in the macrofollicular variant of adult granulosa cell tumor. Their lumens contain basophilic or eosinophilic fluid. Variable layers of granulosa cells line the follicles and occasionally surrounded by mantle of theca cells. The neoplastic granulosa cells have abundant eosinophilic and/or vacuolated cytoplasm and rounded hyperchromatic nuclei. Nuclear grooves are rare. Nuclear atypia in JGCTs varies from minimal to marked. The mitotic rate is also variable but is generally higher than adult granulosa cell tumor.

SLCT

Gross Findings

SLCTs are variable in dimension but frequently are smaller than 10 cm. They mostly are solid, firm, encapsulated, and lobulated masses, typically yellow or tan in color. They are typically unilateral.

Microscopic Findings

SLCTs are derived from mesenchyme and sex cords, which regroup histologically all the embryonic phases of testicular development, from an undifferentiated cord to well-differentiated Sertoli tubes. These tumors contain variable proportions of sertolian and leydigian elements. Tumors with only a sertolian component (Sertoli tumors) belong to the benign group. Tumors containing both types are classified into three groups: (1) benign differentiated forms (androgenic, secretory in 60 % of the cases), (2) intermediate differentiation (immature Sertoli cells), and (3) poorly differentiated forms (sarcomatoid or retiform).

In the forms with poor or intermediate differentiation (primarily epithelial or mesenchymatous), it is possible to see heterogeneous elements. In the largest series of SLCTs with greater than 200 tumors, 18 % contains glands and cysts lined by well-differentiated intestinal-type or gastric-type epithelium, 16 % has microscopic foci of carcinoid tumor, and 5 % has stromal heterologous elements, including islands of cartilage and/or areas of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma [18]. Other heterologous elements that have been associated with SLCTs include hepatocyte-like cells, retinal tissue, neuroblastoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma [19, 20]. Interestingly, tumors that contain heterologous or the retiform type are more frequently cystic.

SCTAT

Gross Findings

SCTAT is a tumor composed of sex cord (Sertoli) cells arranged in simple and complex annular tubules. SCTATs which occur in conjunction with the PJS are usually multifocal, bilateral, and almost always very small tumorlets found incidentally in ovaries. In patients without the PJS, SCTAT is usually unilateral and presents as a solitary, large solid mass up to 33 cm in diameter.

SCTAT typically exhibits well-circumscribed, rounded or oval, epithelial islands made up of ring-shaped, lumenless tubules encircling glassy, acidophilic, PAS-positive, basement membrane-like material.

Others

Gynandroblastomas are probably derived from undifferentiated mesenchyme. This origin would explain their “bisexual” potential; in fact, they could contain a variable amount of granulosa cells and Sertoli–Leydig cells.

In the majority of cases, these tumors are benign; however, certain malignant tumors have been described in the literature, and they are usually large tumors (7–10 cm in diameter).

Also pure Leydig cell tumors are usually benign. In some cases, no evidence of ovarian or testicular differentiation is seen. These tumors belong either to the undifferentiated SCST or to the steroid cell tumors according to cell morphology. Rarely they are malignant but evolution remains unpredictable today [21].

Neoplasms of pure ovarian stroma are mostly benign more than 50 % of them being fibromas. In morphologically ambiguous cases, the reticulin stain, together with mutational analysis of FOXL2, is useful to distinguish adult granulosa cell tumor from fibrothecoma.

Clinical Presentation

The most common symptoms related to SCSTs are pelvic pain, feeling of pelvic pressure due to pelvic mass and menstrual disorders.

GCTs typically occur as an abdominal mass with symptoms suggestive of functioning ovarian tumor. In approximately 5–15 % of patients, hemoperitoneum developed secondary to tumor rupture, and acute pelvic pain due to ovarian torsion could be the first sign [3]. Ascites occurs in about 10 % of cases, and they are asymptomatic in another 10 %.

AGCTs are clinically the most common estrogenic ovarian tumors. Functional symptoms are related to the age and reproductive state of the patient. In prepubertal girls, granulosa cell tumor often induces isosexual pseudoprecocious puberty. In women of reproductive age, the tumor may be associated with menstrual irregularities. In postmenopausal women, irregular uterine bleeding is the most common manifestation due to endometrial alteration such as endometrial hyperplasia that exhibits some degree of atypia (24–80 %) and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (5 %). In addition, GCTs are associated with an increased incidence of breast cancer [5].

About 80 % of JGCT occurs in children, who typically present with isosexual pseudoprecocity. When JGCT occurs after puberty, patients usually present with abdominal pain or swelling, menstrual irregularities, or amenorrhea.

SLCTs are in 95 % of cases confined to the ovaries, tumor rupture is present in 10 % of cases, and 4 % of patients develop ascites. They are usually associated with hyperandrogenic symptoms (30 %), like hirsutism, acne and seborrhea, oligo- or amenorrhea, and in the most severe cases with clitoris hypertrophy, lower tone of voice, and may have laryngeal protuberance and reduction in breast volume. In some cases they have estrogenic functions and in 50 % of the cases are asymptomatic [22–24].

In gynandroblastomas signs of virilescence generally are more frequent than the estrogenic ones.

Tumor Markers and Diagnostics

Diagnostic work-up should include pelvic ultrasound, abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT scan), and chest X-ray. In young patients, serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), α-fetoprotein (AFP) titers, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) can be assessed in order to differentiate germ cell ovarian tumors.

Estradiol is secreted by GCTs, but it is not a reliable marker of disease proliferation. Absence of estradiol secretion is observed in approximately 30 % of patients, and it may be due to a relative lack of theca cells in the tumor stroma. In the rare case of an androgen-secreting GCT, testosterone or its precursors could be used as tumor markers [5].

Inhibin is secreted by granulosa cell tumors and could be a useful marker [25]. Inhibins are mainly formed in granulosa cells and are made of two subunits (subunit bA or bB).

The first report of elevated serum inhibin levels associated with these tumors was published in 1989 by Lappohn et al. Several other studies seem to suggest that inhibin could be a useful marker of GCTs in both pre- and postmenopausal patients [26]. They demonstrated the efficacy of inhibin as a marker for both primary and recurrent disease and showed that a rise in inhibin levels preceded clinical recurrence as early as 20 months. However, elevated inhibin levels are not specific for GCT, as may be observed in epithelial ovarian cancer, especially of the mucinous variety (82 %) [5].

Newer studies using subunit-specific ELISA showed inhibin B to be the major form secreted in GCT and that inhibin B was more accurate than inhibin A to predict primary or recurrent disease. Inhibins act as autocrine and paracrine granulosa cell growth factors, and levels of inhibin reflect the amount of tumor burden.

Another hormone that recently has been evaluated is the anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH); this hormone, in fact, is secreted by granulosa cells only in postnatal females and both prenatally and postnatally by Sertoli cells in the male testis.

AMH is a marker of ovarian reserve, and it disappears in menopausal age or after a bilateral oophorectomy. This marker is highly specific for GCT in postmenopausal women and is related to the extent of disease [27].

AMH and inhibin B level parallel changes predict clinical recurrence as early as 11 months. Several studies show AMH to be a reliable tumor marker with sensitivity between 76 and 100 %. Further studies are required before deciding which tumor marker could be most reliable in detection and management of GCT. One retrospective study suggests AMH to be more sensitive and reliable than inhibin [28].

Regarding instrumental diagnostic work-up, new specific pattern recognition was validated with ultrasound. Van Holsbeke et al. described two typical patterns. The first was a solid mass with heterogeneous echogenicity of the solid tissue as, for example, in necrotic tissue. The second pattern was a multilocular-solid mass containing a considerable amount of solid tissue around relatively small locules, but with no papillary projections. It typically had a ‘Swiss cheese’ appearance owing to the large number of small locules with a variable thickness of solid tissue around the cystic areas [29].

On the contrary 18F-FDG PET/CT is not useful in the staging and follow-up of the great majority of GCTs which are known to cause false-negative results due to very low FDG avidity [30]. There are two possible explanations of this low sensitivity: one is related to the low metabolic and proliferative activity of GCTs as evidenced by weaker MIB-1 (a monoclonal antibody developed against the Ki-67 antigen proliferation index marker); the other explanation could be related to their tendency to recur as cystic lesions [31].

Treatment

Surgery

Early Stage Disease

Surgery represents the most important therapeutic tool for patients with suspected SCSTs at early stage [32].

The staging system for SCSTs is generally adopted from that for epithelial ovarian cancer as originally defined by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system (FIGO staging). However, the prognostic significance of certain features within the FIGO classification (such as positive cytology or ovarian surface involvement) has not been well defined for patients with SCSTs [33].

Surgical approach can be carried out through an open route that allows adequate visualization of the upper abdomen or, in selected cases, by laparoscopy or robotics. Minimally invasive surgery could be considered feasible and safe either for primary surgery or restaging procedures in selected patients [34].

The staging procedure includes infracolic omentectomy, biopsy of the diaphragmatic peritoneum, paracolic gutters, pelvic peritoneum, and peritoneal washings [33].

Many reports indicate that more than 90 % of these neoplasms are unilateral and confined to the ovary. Thus, a fertility-sparing surgery with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging seems to be reasonable in patients wishing to preserve their fertility, in the absence of extra-ovarian spread. For young women who can be offered conservative therapy, uterine curettage should be performed before surgery, because of the frequent association of GCT with endometrial hyperplasia (55 %) or endometrial adenocarcinoma (4–20 %).

Removal of the other ovary and total abdominal hysterectomy are recommended in postmenopausal women, and it is advisable at the conclusion of childbearing, though this issue is still controversial. Some authors reported a worse survival for patients undergoing fertility-sparing surgery, but this was related mostly to a higher stage of disease in the group analyzed [35].

Zanagnolo and Zhang published the two largest series about conservative treatment.

In the series of 63 cases published by Zanagnolo et al., a conservative surgical treatment was performed in 23 % of early stage tumors; none of them recurred, and five of 11 patients became pregnant after treatment [36].

Zhang et al., in a series of 110 patients, showed no statistical difference on survival between the conservative vs demolitive treatment (94.8 % and 94.9 %, p = 0.38) [37].

SLCTs are frequently low-grade malignancies, although occasionally a poorly differentiated variety may behave more aggressively. Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with preservation of the contralateral ovary and the uterus is now considered the adequate surgical treatment for patients in childbearing age.

There is no consensus about the role of systematic lymphadenectomy in SCSTs because of the very low incidence of retroperitoneal metastases in early stages [38, 39].

Thrall et al. confirmed previous reports and strengthened the principle that routine lymphadenectomy is unnecessary in the primary surgical management of SCSTs; they reviewed 47/87 patients, who had some nodal tissue examined as part of the initial or restaging procedure, and all examined nodes were negative [39–41].

In a more recent study of Shim et al., 578 patients were analyzed, and lymph node metastases were not detected in the 86 patients who underwent lymph node removal. This study confirms that the incidence of lymph node metastases in patients with clinical stage I and II SCSTs is low [34].

Node dissection should be carried out only in those cases with evidence of nodal abnormality.

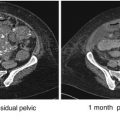

Advanced Stage and Recurrent Disease

In advanced stage SCSTs, surgery is necessary to establish a definitive pathological diagnosis, to perform staging, and to achieve optimal debulking. In patients with advanced stage disease or with bilateral ovarian involvement, abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed with a careful surgical staging/cytoreduction. This includes a thorough exploration of abdominal cavity, washing for cytological analysis, multiple peritoneal biopsies, omentectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic lymph node sampling/dissection. Although no scientific evidence exists on the role of cytoreduction in these tumors, an effort should be made to remove all metastatic disease.

Adjuvant Treatment

Early Stage Disease

The majority of SCSTs are diagnosed at early stage (60–95 %). Given the indolent nature and the overall good prognosis, there are no data to support any kind of postoperative adjuvant treatment for patients with stage I who underwent an adequate staging procedure. Some authors suggest adjuvant therapy for stage IC with high mitotic index with preoperative tumor rupture [5, 35]. For SLCTs, postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered for those patients with stage I poorly differentiated tumors or with heterologous elements. Platinum-based chemotherapy is the treatment of choice. The most commonly used regimen is the BEP combination (bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin) for three courses [42–44].

Alternative chemotherapy options include etoposide plus cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and cisplatin, paclitaxel and carboplatin, or platinum agent alone.

Advanced Stage and Recurrent Disease

In metastatic and recurrent GCTs, debulking surgery continues to be the most effective treatment.

The rarity of GCTs has made it impossible to conduct a well-designed randomized study assessing the value of postoperative therapy after debulking surgery.

Chemotherapy

The rarity of this disease, the different regimens utilized, and the tendency for late relapses make it difficult to draw definitive guidelines. Platinum-based chemotherapy has been the treatment of choice for the past decade with an overall response rate of 63–80 % for advanced and relapsed disease [50].

In the early 1980s, the first promising regimens reported in the literature were the combination of cisplatin with doxorubicin (AP) and the three drugs regimen cisplatin, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (CAP). The response rate was 100 % and 63 %, respectively [47, 51].

Later, PVB (cisplatin-vinblastine-bleomycin) was reported as an effective regimen in two Italian studies and in one EORTC (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer) series, with response rates ranging from 57 to 82 % [46, 48, 52]. Despite these promising results, severe hematologic and non-hematologic toxicities were reported, making this regimen unfeasible in most patients.

The combination of platinum with bleomycin and etoposide (BEP) was subsequently tested.

Gershenson et al. observed an overall response rate of 83 % in a series of nine patients with poor-prognosis SCSTs treated with BEP. Median progression-free survival was 14 months, and median overall survival was 28 months [49].

In 1999, Homesley reported the results of a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study on the use of BEP in a series of 56 patients. In this trial, with a median follow-up of 3 years, 11 (69 %) of 16 patients in the primary advanced disease category and 21 (51 %) of 41 of recurrent patients were progression-free. However, this active regimen was associated with a severe toxicity, in particular, Grade 4 myelotoxicity occurred in 61 % of patients [43].

In 1995 Tresukosol reported the first case report on paclitaxel response of recurrent GCTs [53].

In a more recent retrospective study from Brown et al., the efficacy and side effects of taxanes, with or without platinum, were historically compared to BEP in the recurrent and advanced setting (222 patients). For newly diagnosed patients treated with BEP versus taxane, no significant differences in response rate (82 % for both regimens), median overall survival (97.2 months for BEP and more than 52 months for taxane), and median progression-free survival (46.1 months for BEP and more than 52 months for taxane) were observed. Median OS and PFS for taxane were not reached.

Among patients treated for recurrent measurable disease, the response rate was higher, but not statistically significant, with BEP (71 %) compared to taxane (37 %); the median progression-free survival was 11.2 and 7.2 months, respectively. The presence of platinum in the taxane-based combination correlated with response in patients with recurrent disease: 60 % with taxane–platinum comparing with 18 % with taxane alone. Many of the latter patients, however, had received platinum before. Toxicity profile was better with taxane regimens [54].

Currently, BEP regimen for three to six cycles (last three without bleomycin) or carboplatin/paclitaxel is recommended for advanced and recurrent SCSTs. A Gynecologic Oncology Group phase II trial is currently ongoing, to compare BEP versus the combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin for patients with newly diagnosed and chemo-naïve recurrent metastatic SCSTs of the ovary (GOG0264) [55].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree