Ovarian

Simple cyst

Corpus luteum

Follicular cyst

Benign serous

Benign mucinous

Complex

Endometrioma

Dermoid

Malignant ovarian tumor

Malignant metastatic tumor

Malignant tumors

Epithelial

Germ cell

Sex cord

Extraovarian

Ectopic pregnancy

Tubo-ovarian abscess

Hydrosalpinx

Pedunculated fibroid

Adnexal masses encountered incidentally at time of abdominal surgery can present as a challenge to the surgeons. Proper management of these masses often depends on patient’s age and findings from preoperative workup. Ideally preoperative workup should include a transvaginal ultrasound and evaluation of tumor markers. Simple-appearing cystic masses with normal tumor markers are less suspicious for malignancy, whereas complex cystic masses with solid components and elevated tumor markers may raise concern for an adnexal malignancy. However, an understanding of possible types of adnexal masses, both benign and malignant, may assist the general surgeon in appropriately managing adnexal masses incidentally found at time of surgery.

Generally when a suspicious mass is encountered, if a gynecologic oncologist is available, it is always advisable to call for an intraoperative consultation in the case of gynecologic malignancy. When either a gynecologist or gynecologic oncologist is not available or frozen section is unable to yield definitive histologic diagnosis, conservative approach of removing the abnormal adnexal mass while preserving the contralateral adnexa should always be considered.

Additional surgical procedures including hysterectomy, contralateral salpingo-oophorectomy can be performed if needed in a subsequent setting. The conservative approach will allow the pathologist to properly analyze the entire specimen and the gynecologic oncologist to have the opportunity to counsel the patient and her family regarding any further additional surgical procedures and adjuvant therapies that may be required prior to definitive surgery.

In the following section, different types of ovarian neoplasm will be discussed. Salient features will be presented to assist the surgeons and gynecologists in understanding the ovarian tumor that is encountered during the surgery. Specific surgical approaches as they pertain to adnexal masses in women of different age groups will then be discussed in order to aid in intraoperative decision-making.

Histologic Types of Ovarian Neoplasms

The ovaries are made up of three types of cells: epithelial cells, germ cells, and stromal cells. Generally, adnexal neoplasms are grouped into five larger categories based on histologic type according to the World Health Organization classification system. The most commonly encountered are: epithelial, germ cell, sex cord-stromal tumors, metastatic tumors, and a miscellaneous group. There exist both benign and malignant entities in the three larger subtypes. Epithelial ovarian tumors are the most commonly encountered, which account for approximately 75 % of all ovarian tumors and 90–95 % of ovarian malignancies. Germ cell tumors are the second most common, accounting for about 15–20 % of ovarian neoplasms. Approximately 5–10 % of all ovarian neoplasms are categorized as sex cord-stromal tumors [2–4] (Table 29.2). Lastly, it must always be considered that an ovarian tumor may represent metastatic disease from another primary, most commonly from the breast, colon, stomach, and other gynecologic organs such as the endometrium or the cervix.

Table 29.2

Ovarian tumors and incidence

Histologic types | Incidence of ovarian tumors |

|---|---|

Epithelial ovarian tumors | 75 % |

Germ cell tumors | 15–20 % |

Sex cord-stromal tumors | 5–10 % |

Epithelial Tumors

Epithelial-type tumors are the most commonly encountered of the ovarian tumors, and the majority of these tumors are benign [2, 4]. Epithelial-type tumors are classified as either benign, malignant, or tumors of low malignant potential. Epithelial-type tumors can be further divided according to the type of cells into which they differentiate: serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, and Brenner tumors. Malignant tumors of epithelial origin are then further subdivided according to their degree of differentiation (well, moderately, and poorly differentiated neoplasm), which is reflected in their clinical behavior. Tumors of low malignant potential, also referred to as borderline tumors, represent a group of tumors that demonstrate a pattern of proliferation greater than those found in benign tumors, but lacking destructive invasion of the stromal components of the ovary. Borderline tumors have a substantially more favorable prognosis compared to their malignant counterpart, with an overall 10-year survival of 83–93 % [4, 5].

The pattern of spread among the epithelial tumors is unique in that it involves exfoliation of surface ovarian tumor into the peritoneal cavity, resulting in peritoneal surface spread. Important risk factors have been identified for malignant epithelial tumors. Among these the strongest correlation has been found with BRCA mutations. Approximately 5–10 % of ovarian cancers are associated with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes. The average lifetime risk for ovarian cancer in patients with BRCA1 mutations is approximately 30–40 % and a smaller risk for patients with BRCA2 mutations (10–18 %) [6]. Management of patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 are further discussed in Chap. 6, BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Breast Cancer and Ovarian Cancer. Other important risk factors include age, nulliparity, obesity, and family history. Oral contraceptive use has been found to be protective [2, 4, 7, 8].

Serous epithelial tumors are the most common of all ovarian tumors (Figs. 29.1, 29.2, and 29.3). These tumors are subcategorized into benign, malignant, and tumors of low malignant potential. The mean age at presentation of malignant serous tumors is in the sixth decade of life, and this tumor type is uncommon in women less than 35 years of age. Serous carcinomas are further divided into low-grade and high-grade types. Low-grade histologic types tend to be slower growing with better survival outcomes, whereas high-grade serous carcinomas are associated with rapid growth, advanced presentation of disease, and poor survival [2, 9].

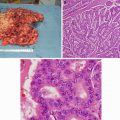

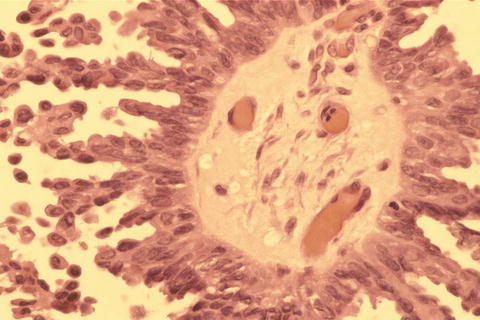

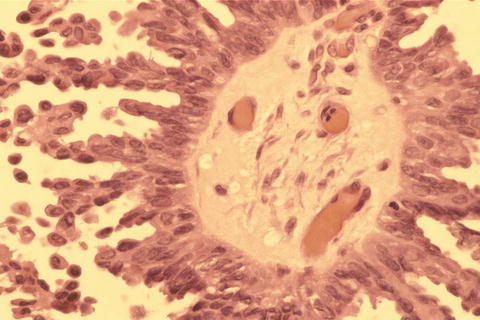

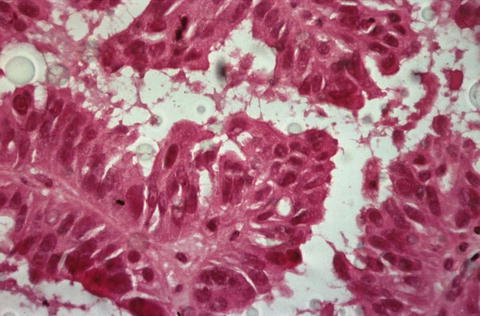

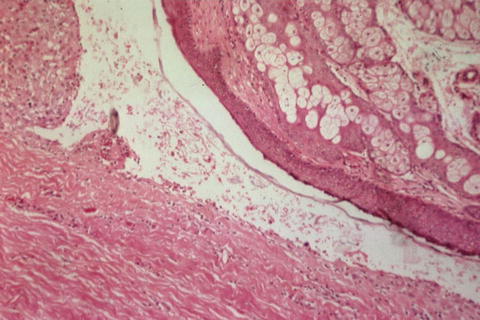

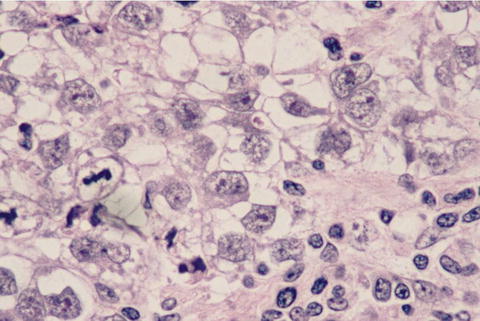

Fig. 29.1

Microscopic view of serous cystadenoma of low malignant potential (micropapillary type)

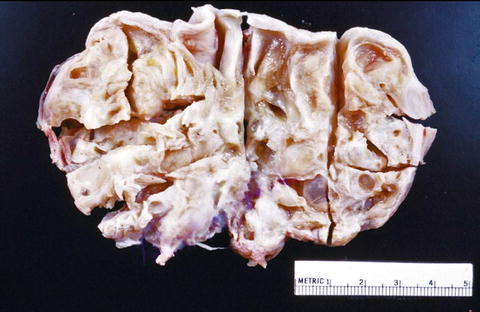

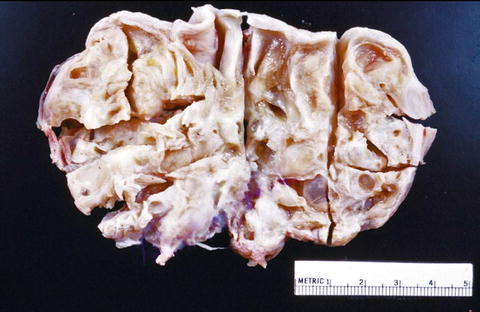

Fig. 29.2

Gross specimen of serous cystadenocarcinoma

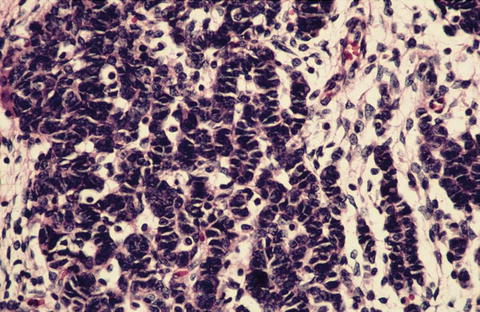

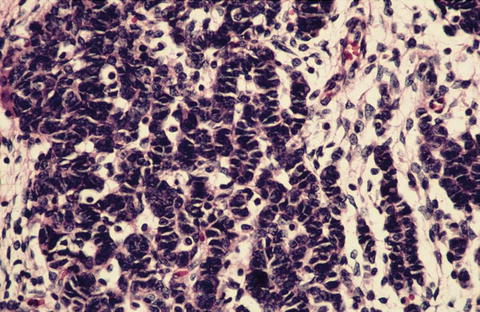

Fig. 29.3

Microscopic picture of serous cystadenocarcinoma

Benign and low malignant potential serous tumors tend to present slightly earlier in life, more commonly in and before the fifth decade of life [2]. Well-staged borderline tumors that are confined to the ovary have an excellent prognosis. These tumors are bilateral in approximately one-third of cases; therefore, in cases of fertility-sparing surgery, the contralateral ovary must be carefully inspected and preserved if it appears normal.

Mucinous tumors like serous tumors are divided into benign, malignant, and low malignant potential types, with benign being the most common. All three types classically present as very large ovarian tumors with a mean size of 18 cm. These tumors are less common than their serous counterpart representing only 10 % of epithelial-type ovarian tumors. The age distribution of these tumors is similar to that of the serous types with malignancy occurring more commonly beyond the fifth decade of life. It must be kept in mind when encountering this tumor type that these masses may represent metastasis, most commonly from the gastrointestinal tract. These tumors are usually bilateral in nature. This can make diagnosis challenging, as the ovarian tumor may be the first visible sign of disease. Careful inspection of the gastrointestinal tract should be carried out when mucinous tumor is encountered incidentally and routine appendectomy is recommended for patient with malignant ovarian mucinous tumor.

Endometrioid tumors make up a smaller portion of epithelial-type ovarian tumors. Like other epithelial tumors, they are also classified as benign, malignant, and borderline. The age distribution is similar to other epithelial-type tumors. The malignant tumors can present synchronously with endometrioid-type endometrial cancers of the uterus in up to 30 % of cases.

Clear cell tumors are uncommon and are classically thought to be more aggressive than the other epithelial tumors; however, data regarding this is inconsistent. Clear cell tumors can present as tumors of low malignant potential; however, it is very difficult to differentiate these from the malignant subtype. Clear cell tumors are most often associated with endometriosis.

Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

These tumors account for 15–20 % of all ovarian tumors but represent less than 5 % of all ovarian malignancies. The benign mature cystic teratoma, also referred to as a dermoid cyst, makes up the largest component of tumors in this category and is the most common ovarian neoplasm overall (Figs. 29.4 and 29.5).

Fig. 29.4

Gross specimen of a mature cystic teratoma

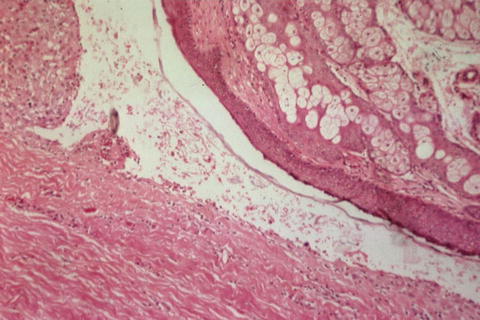

Fig. 29.5

Microscopic picture of a mature cystic teratoma

Dermoids often contain components from all three embryonic germ layers, but most commonly of the ectoderm layer containing elements such as hair and sebum. These tumors often have a high-fat content, and their buoyancy places these tumors at higher risk for ovarian torsion. It is important in cases of dermoid cysts that thorough inspection of the other ovary is performed, as 20 % of these cysts are bilateral. As these tumors are usually benign, conservative approach such as ovarian cystectomy should be attempted if possible. Tumors of this category also represent the most common ovarian malignancies affecting women younger than 20 years of age, and in fact, approximately 70 % of these tumors occur in this age group. Malignant tumors in this category include dysgerminomas, endodermal sinus tumors (yolk sac tumors), immature teratomas, mixed germ cell tumors, and embryonal tumors.

Dysgerminomas are the most common of the malignant type, and although they can be seen in patients with normal karyotypes, they are also classically seen in patients with gonadal dysgenesis, such as patients with testicular feminization. The risk of bilaterality is approximately 10 %, and the contralateral ovary should be inspected carefully. The risk of dysgerminomas peaks at age 20 but can range from age 6 to 40 depending on the histologic type. These tumors tend to be predominantly solid, large fleshy masses [10, 11].

Yolk sac tumors are the next most common of the germ cell tumors and tend to grow quite rapidly (Figs. 29.6 and 29.7). These tumors are typically unilateral; however, metastasis to the contralateral ovary may occur. In adults, yolk sac tumors account for approximately 15 % of all germ cell tumors. Yolk sac tumors are relatively more common in children. These tumors tend to be more cystic than dysgerminomas and may exhibit more substantial areas of necrosis. Yolk sac tumors are aggressive and these patients require adjuvant chemotherapy [10, 11].

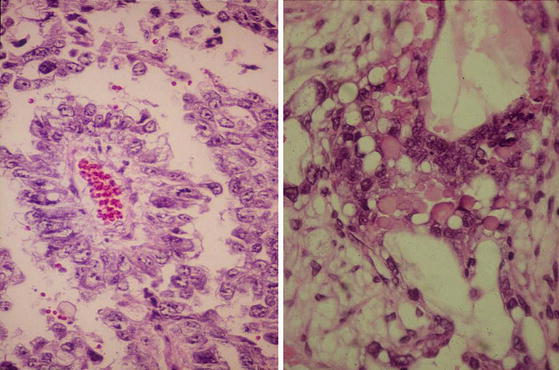

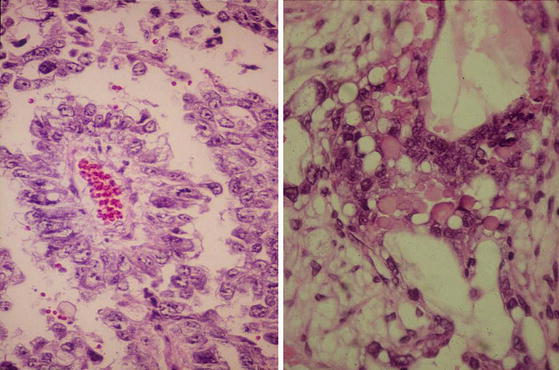

Fig. 29.6

Gross specimen of yolk sac tumor

Fig. 29.7

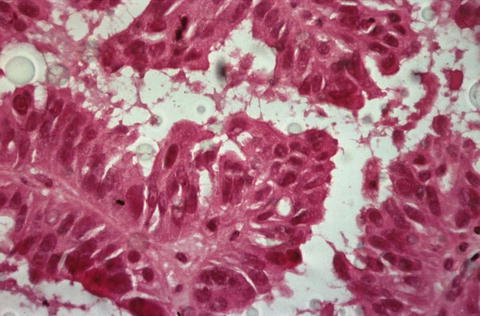

Microscopic picture of yolk sac tumors

Immature teratomas are the third most common malignant tumor in this category (Figs. 29.8 and 29.9). It contains variable amounts of immature tissue from all three germ cell layers. Again, most patients are diagnosed as stage I disease, and survival is most closely associated with grade of the tumor. Survival of women with grade 1 disease is 100 %, grade 2 disease is 70 %, and grade 3 disease is 33 %. Adjuvant therapies are usually recommended for patients with stage I grade 3 tumors or advanced stage diseases [11].

Fig. 29.8

Gross specimen of immature tumor

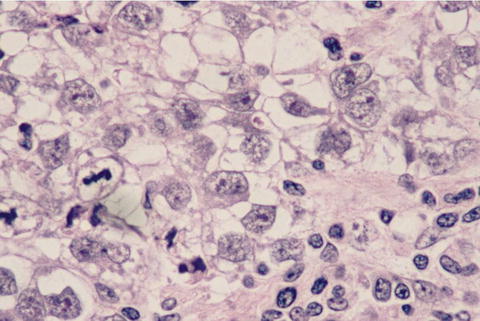

Fig. 29.9

Microscopic picture of immature tumor

Ovarian Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors

Sex cord-stromal tumors are significantly less common and comprise only 5–10 % of all ovarian tumors. These tumors are derived from the sex cord and stromal components of the ovary. Because of this derivation tumors of this type can contain a variety of cell types including granulosa cells, theca cells, lutein cells, Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, and fibroblasts. Fibromas and thecomas make up the benign category, which rarely demonstrate malignant counterparts. Fibromas account for the most common tumor among the sex cord-stromal tumors. Often with sex cord-stromal tumors, the histologic components of the tumor are a combination of more than one of these types of cell.

Granulosa cell tumors are the next most common tumors in this category (Figs. 29.10 and 29.11). They are an estrogen-producing malignant type of ovarian tumor. Granulosa cells comprise 70 % of the tumors in this category and are divided in adult type and juvenile type, which differ morphologically and in the age distribution of patients affected. The adult-type histology is the more common of the two accounting for approximately 95 % of cases. Both types often present with signs of unopposed estrogen (abnormal vaginal bleeding, precocious puberty, etc.); however, the juvenile-type granulosa cell tumor is known to be far more aggressive with one small study demonstrating only a 23 % survival in stages II–IV disease. The average size of tumor at presentation is 12 cm, and these tumors should be suspected in patients from this age group who present with large unilateral adnexal masses [4, 12, 13].

Fig. 29.10

Gross specimen of granulosa-theca cell tumor

Fig. 29.11

Microscopic picture of juvenile granulosa cell tumor

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are rarer than granulosa cell tumors, making up less than 1 % of all ovarian tumors. In some cases, they can be associated with virilization as they may secrete testosterone but like granulosa cell tumors often present with symptoms of an abdominal mass and menstrual disorders. These tumors are also quite large at presentation with an average 16 cm tumor size noted at time of detection. Also like granulosa cell tumors, these tumors tend to be diagnosed in early stage disease with only 2–3 % demonstrating extraovarian spread at time of diagnosis [4].

Fallopian Tube and Peritoneal Surface Tumors

Benign cysts of the fallopian tube are referred to as paratubal cysts. They are often simple and of no consequence. Therefore, surgical intervention is not necessary for this incidental finding. Malignant tumors of the fallopian tube and primary peritoneal surface tumors behave very similarly to epithelial ovarian malignancies. In fact, recent studies have suggested that high-grade serous carcinoma may actually originate from the fimbriated end of the fallopian tubes. Given the proximity of the fallopian tube to the ovary, and the typically advanced nature of these malignancies, it is often difficult to distinguish between primary fallopian tube and primary ovarian tumors. In contrast, although primary peritoneal tumors behave similarly to epithelial ovarian malignancies, at time of diagnosis, the ovaries are either only minimally involved or not involved at all. Carcinomatosis can be present in all three entities [14].

Evaluation of the Surgical Specimen

Diagnosis is typically made via frozen section, which is both highly specific and sensitive in the evaluation of adnexal masses. The sensitivity and specificity are highest for malignant and benign tumors (88–97 %), with less accuracy being seen in the diagnosis of borderline tumors (33–62 %). Once a diagnosis of adnexal malignancy is made by frozen section, an appropriate staging procedure should be initiated. However, in cases of uncertainty, a conservative approach should be taken. The patient can always return at a later time to complete the staging procedure once a final pathologic diagnosis is achieved [15–17].

Tumor Markers

Although tumor markers are not considered useful for routine screening in ovarian tumors, they may assist with preoperative diagnosis by increasing suspicion of particular tumor types. Tumor markers are also useful after initial diagnosis for evaluation of therapeutic response and can be an indicator of recurrent disease (Table 29.3).

Table 29.3

Tumor markers by histologic subtype

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree