Historically termed “carcinoid” and “islet cell tumors,” pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) comprise a rare group of tumors that range from the spectrum of well-differentiated functional tumors to nonfunctional poorly differentiated carcinomas. This group of tumors often produces hormones resulting in clinically apparent symptoms. Derived from the islet cells of Langerhans, the first islet cell tumor was reported in 1902.1 Since then, 10 different categories of PNETs have been described, with all but one category being associated with a functional syndrome.

PNETs arise from pluripotent cells in the ductal and acinar epithelium of the pancreas (Table 49-1). While most PNETs occur infrequently, with one to five cases/million/year being newly diagnosed, autopsy reports reveal that these tumors may have an incidence of up to 1.5%, suggesting that many of these tumors may be asymptomatic.2,3 Optimal treatment for locoregional control of tumors includes surgical resection when feasible. Unfortunately, the malignant potential of these tumors cannot always be evaluated on histopathology alone, as the determination of malignancy requires evidence of local invasion or findings of metastases. With the exception of insulinomas, many PNETs may already have metastasized by the time of diagnosis.4,5 Malignant PNETs often have an indolent course, with a more favorable prognosis compared to that of other pancreatic tumors (i.e., pancreatic adenocarcinoma). These tumors are less sensitive to traditional chemotherapy; this raises the importance of an aggressive surgical approach, as well as the potential for adjunctive treatments including radiofrequency ablation, chemoembolization, and molecular targeted therapies.

Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

| Islet Cells | Active Secreted Hormone/Agent | Tumor |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Glucagon | Glucagonoma |

| Beta | Insulin | Insulinoma |

| Delta | Somatostatin | Somatostatinoma |

| D | Gastrin | Gastrinoma |

| A to D | VIP and other agents | VIPoma |

| 5HT | Carcinoid | |

| Melanocyte-stimulating hormone | ||

| Interacinar cells | ||

| F | Pancreatic Polypeptide | PPoma |

| Enterochromaffin cells | 5HT | Carcinoid |

PNETs comprise approximately 1.3% to 2.8% of all new pancreatic malignancies each year.5–7 Historically, the incidence of nonfunctioning PNETs was thought to be lower than functional PNETs. As a result of technologic improvements and increased use of cross-sectional abdominal imaging, this has been proven to not be the case. Recent reports have shown that only 15% to 30% of PNETS are functional; therefore, the overwhelming majority is now thought to be nonfunctional.3,5,8,9

Functional PNETs have the ability to produce a variety of hormones that result in well-defined clinical syndromes related to the particular secreted hormone. Excessive insulin secretion from an insulinoma can result in hypoglycemia; excessive gastrin production can result in diffuse peptic ulcer disease seen in patients with a gastrinoma. The presentation of diabetes and necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) is typical of that seen in patients with a glucagonoma. Somatostatinomas characteristically result in hyperglycemia, steatorrhea, and cholelithiasis.

PNETs are often seen in sporadic cases, but also can be part of inherited syndromes. Four different inherited syndromes are associated with the development of PNETs. These include multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL), von Recklinghausen’s disease/neurofibromatosis type 1 (VR/NF1), and tuberous sclerosis. All syndromes are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, and there is a variable phenotypic penetrance of PNETs.

The diagnosis of functional PNETs can be difficult, as they occur infrequently and can often be overlooked by physicians due to unfamiliarity with these disease processes. In addition, patients may be unaware of symptoms of hormonal excess since many will compensate for a particular clinical syndrome by adjusting their dietary intake, as in the case of patients with an insulinoma. The goals of initial evaluation should be to assure a timely and accurate diagnosis of the PNET, localization of the primary tumor, and staging based on imaging. The primary treatment for localized PNETs consists of fluid resuscitation, control of hormone excess (for functional tumors), and surgical excision of the tumor. Even small tumors should be considered for resection due to their underlying malignant potential. Localized and early tumors can be cured by adequate surgical resection. For unresectable tumors or those with metastatic disease, treatment is geared toward palliation through control of hormone excess and limiting tumor growth with chemotherapy. Surgical resection may still be indicated if the tumor is locally resectable, and metastasectomy is feasible. This chapter discusses PNETs other than insulinomas and gastrinomas, which are presented elsewhere in this book.

First described by Becker in 1942, glucagonoma tumors comprise a rare functional NET that typically presents in the fifth decade of life. Pathologically, they appear as well-encapsulated, firm tumors, and arise from the alpha cells of the pancreas.10,11 This allows for the detection of this particular tumor through immunoperoxidase staining or by in situ hybridization targeting glucagon mRNA.

Typically arising in the tail of the pancreas, these tumors may vary in size from 2 to 25 cm by the time of diagnosis. The majority acts in a malignant fashion, and they often already have metastasized at the time of diagnosis. Initially thought to have a female preponderance, recent reports show a more even distribution between the genders.10 Glucagonoma tumors are rarely encountered in patients with MEN type I, who typically have a family or personal history of primary hyperparathyroidism, pituitary tumors (adenomas), other PNETs, and carcinoid tumors.

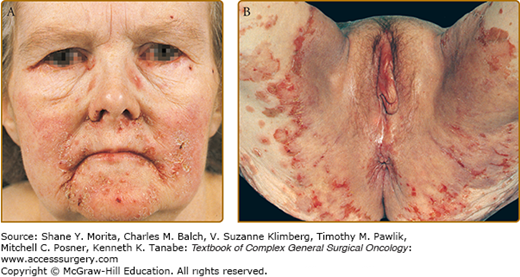

Patients typically present with findings of hyperglycemia and hyperglucagonemia. Glucagonoma tumors are classically associated with a clinical syndrome including NME (Fig. 49-1), chelitis, glossitis, diabetes mellitus, anemia, weight loss, cachexia, diarrhea, venous thrombosis, and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Weight loss and NME occur in 65% to 70% of patients at the time of diagnosis. Chelitis and glossitis are often pathognomonic for glucagonoma. Diabetes is seen in 75% to 95% of all patients with this syndrome, while venous thrombosis occurs in 30% of patients.12,13 Neurologic symptoms are rare, but can include ataxia, dementia, optic atrophy, and proximal muscle weakness.

FIGURE 49-1

The glucagonoma syndrome, necrolytic migratory erythema. Flaccid and papulovesicular lesions (A) with erosions, crusting, and fissures around the orifices, and (B) appearing as geographic, circinate “necrolytic migratory erythema” in the groin. (A and B are not the same patient.) (Reproduced with permission from Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, Inc; 2012.)

A thorough history and physical examination are important for all patients. NME also can be seen in patients with liver disease, pancreatitis, celiac disease, and lung cancer. However, the presence of NME or glossitis and chelitis should elicit further evaluation for glucagonoma. If an NME diagnosis by clinical exam is not clear, punch biopsies taken from the edges of the active lesions often show characteristic epidermal necrosis (Fig. 49-1). Multiple biopsies of the NME lesions are recommended.14

Specific laboratory findings include normochromic, normocytic anemia, present in nearly 90% of patients, and an elevated fasting serum concentration of glucagon (>500 pg/mL, normal 50 to 200 pg/mL), which is diagnostic for glucagonoma.15 However, glucagonoma patients may have serum glucagon levels below 500 pg/mL; therefore, if clinical suspicion is high, additional testing should be undertaken. Performing a study of the nutritional status of the patient is important in order to correct nutritional deficits; this test must evaluate the serum level/concentration of amino acids, zinc, and essential fatty acids.

Determining the level of transaminases, bilirubins, and alkaline phosphatase is important in order to detect hepatic metastases. The serum level of chromogranin A (CgA) is sensitive but nonspecific for determining the presence of a glucagonoma. Stimulation tests with arginine, secretin, or tolbutamide, which rapidly stimulate plasma glucagon levels in patients affected by glucagonoma, offer little to the diagnostic evaluation.16

The detection of telomerase and the quantification of the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) protein subunit have been proposed for distinguishing clinically benign from malignant endocrine tumors. In a few reported cases, malignant glucagonoma showed telomerase activity. The quantification of hTERT messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) has been used in clinical practice to exclude malignancy.17

Originally discovered as an inhibitor of growth hormone release, somatostatin is known to inhibit a variety of gastrointestinal processes. Patients with somatostatinoma present with symptoms related to excess somatostatin secretion; this manifests in a classic triad of diabetes mellitus, diarrhea (second to malabsorption), and gallstones. Somatostatinomas are among the rarest of the PNETs.18,19 Somatostatin is produced by paracrine and endocrine-like D cells that are scattered throughout the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas, and it acts to inhibit gastrointestinal endocrine secretion. These cells function by sampling the luminal contents and acting through a paracrine feedback with inhibitory physiologic effects. This results in decreased endocrine and exocrine secretion and reduced blood flow, slowing gastrointestinal motility, gallbladder contraction, and inhibiting secretion of most intestinal hormones. The mean age of patients at diagnosis is 50 years, with an equal distribution between men and women. Most somatostatinoma tumors are malignant, frequently with large primary tumors (>5 cm) and metastatic disease at the time of initial diagnosis.

The definition of somatostatinoma is debated in the current literature, as most patients with somatostatinoma do not manifest the overt clinical syndrome.19,20 Inhibition of insulin secretion is mild and often leads to only mild hyperglycemia. Gallstones may be asymptomatic. The inhibition of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate secretion results in decreased intestinal absorption with diarrhea and steatorrhea; however, this is often mild. Somatostatinomas can be found incidentally on cross-sectional imaging, and these patients may not have overt symptoms. While somatostatin tumors can be found in the duodenum and pancreas, it is the pancreatic tumors that are more likely to be associated with the clinical syndrome described above.15

If a somatostatinoma is suspected, serum somatostatin levels should be obtained. Pancreatic somatostatinoma patients will have elevated serum somatostatin levels, often >50 times higher than normal. In patients with intestinal somatostatinomas, levels can be lower, and provocative tests with tolbutamide and arginine may need to be done.

VIPoma tumors are rare NETs that secrete vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP); the incidence is approximately 1 in 10 million people/year.21 The majority of tumors arise within the pancreas; however, other malignancies may cosecrete VIP, including bronchogenic carcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, pheochromocytoma, hepatoma, and other adrenal tumors.3,22 VIPomas are usually solitary tumors, often larger than 3 cm in size at the time of diagnosis. More than 75% of tumors are found localized in the tail of the pancreas, with 60% to 80% of patients having metastases at the time of diagnosis.21 Up to 5% of patients with VIPoma have associated MEN type I syndrome.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree