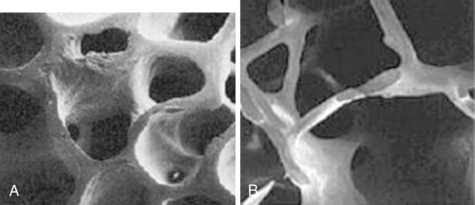

43 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Differentiate primary and secondary osteoporosis and understand the medical conditions and medications associated with secondary osteoporosis. • Understand how to determine individual fracture risk by identifying risk factors and secondary causes and determining bone mineral density. • Interpret bone mineral density measurements and understand their use in predicting fracture risk and determining the need for drug therapy. • Understand recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the National Osteoporosis Foundation for bone density testing. • Understand recommendations for calcium and vitamin D intake and how to determine if a patient requires supplementation. • Describe the drugs currently approved for primary and secondary prevention, their effectiveness in preventing fractures, and potential adverse effects. Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal condition characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue that increases bone fragility and risk for fractures.1 It is diagnosed on the basis of the presence of a fragility fracture or by bone mass measurement criteria. A fragility fracture results from forces that would not normally cause a fracture, such as a hip or wrist fracture from falling from standing height or a vertebral compression fracture. In the absence of a fracture, osteoporosis can be diagnosed by measuring bone mineral density (BMD). Results are expressed as a T-score, which is the difference between an individual’s BMD measurement and normal values from a young healthy reference group. The World Health Organization developed definitions for normal, low, and osteoporotic levels of BMD based on T-scores for the spine, hip, or wrist for postmenopausal women and men age 50 and older.2 By these criteria, bone density is normal for T-scores of −1.0 and higher; low for T-scores between −1.0 and −2.5 (also referred to as osteopenia), and osteoporotic for T-scores of −2.5 or lower (Box 43-1). However, T-scores identify only one aspect of the condition. Other important components, such as the rate of bone loss and quality of bone, are not currently measured. Low bone density, osteoporosis, and related fractures are common in older adults. Estimates in 2012 indicated that as many as 50% of Americans older than age 50, or 12 million individuals, would be at risk for osteoporotic fractures during their lifetimes.1 Fracture rates for women are higher than for men, and rates are highest in whites compared to other racial groups, although rates for all demographic groups increase with age.3–5 Osteoporosis-related fractures occur at many anatomic sites but are most common at the vertebrae, hip (proximal femur), and wrist (distal radius). All types of fractures are associated with increased mortality.6–8 Approximately one third of men with hip fractures will die during the subsequent year, a higher rate than for women.9 Nonfatal fractures at any site can impair function and quality of life, cause chronic pain and disability, and result in high costs for health care and lost productivity. Bone mass is determined by genetic factors, nutrition, physical activity, and general health, and it peaks during early adulthood. Bone health is maintained by the process of bone remodeling, in which old bone is replaced by new. Bone loss occurs when bone removal outpaces replacement. This process also causes alterations in the trabecular plates of bone, which further weakens bone structure (Figure 43-1). Bone loss progresses with aging and may be particularly active for women during menopause. Although bone loss and structural fragility are important causes of fracture, several others are contributory, such as the factors influencing falls (Figure 43-2). Figure 43-1 Micrographs of normal (A) versus osteoporotic (B) bone. (From National Osteoporosis Foundation. Physicians’ guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. http://www.nof.org.) Osteoporosis and fractures may result from several contributing causes, and it is important to understand a patient’s overall medical condition before planning interventions, particularly drug therapy. Individual risks for osteoporosis and fractures need to be reassessed periodically because changes in health status, such as the diagnosis of a new condition or initiation of a new medication, can influence a patient’s risk profile. Patients with previous osteoporosis-related fractures are at high risk for subsequent fractures and are the most likely to benefit from osteoporosis drugs. Most patients are able to recall having had a previous fracture that required medical attention. Fractures are usually well documented in medical records and validated by radiographs. Tracking follow-up care is usually more difficult because it often occurs outside of the immediate care setting. As a result, evaluations for osteoporosis are often missed, drug therapy is frequently not prescribed, and rates of subsequent fractures are generally high.10,11 Fractures that do not require immediate medical attention are often not recognized, particularly the majority of vertebral fractures with mild or no symptoms. Nonetheless, undetected vertebral fractures are also important in establishing the diagnosis of osteoporosis and determining needs for drug therapy, and can easily be seen on vertebral x-rays. The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends vertebral imaging for older men and women.12 Osteoporosis may occur without a known cause (primary osteoporosis) or can occur as the result of another condition (secondary osteoporosis). It is important to identify potential secondary causes before determining the need for osteoporosis drugs. Common secondary causes include dietary deficiencies of calcium or vitamin D; medications (including glucocorticoids); health conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis; and several others that are often undetected (Box 43-2). Metabolic bone diseases other than osteoporosis, such as hyperparathyroidism or osteomalacia, may be associated with a low BMD. Tests to diagnose secondary causes include complete blood counts and blood chemistries, liver function, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), serum 25(OH)D, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and 24-hour urine calcium, as well as special studies in selected patients. Risk factors are also useful in determining needs for bone density testing and osteoporosis drugs. Several methods to calculate a patient’s individual risk for fracture based on key risk factors derived from epidemiologic studies have been developed and tested. Although models vary, most are modest predictors of fractures, and the results of simple versus complex models are similar.13 The Fracture Risk Assessment Model (FRAX), developed by the World Health Organization,14 calculates a patient’s 10-year probabilities of either a major osteoporotic fracture (spine, hip, or wrist) or, specifically, a hip fracture based on 11 risk factors (Box 43-3). FRAX has been validated for both men and women. Calculations can be made with and without bone density results using a publicly accessible web-based calculator.15 The NOF has issued treatment recommendations based on specific 10-year risk thresholds calculated by FRAX (20% and higher risk for major osteoporotic fractures; 3% and higher risk for hip fracture).12 However, this approach has not been tested in drug trials, and it is not yet known how effective these thresholds would be in reducing fractures in actual patients.

Osteoporosis

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Fracture history

Identification of secondary causes and risk factors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Osteoporosis