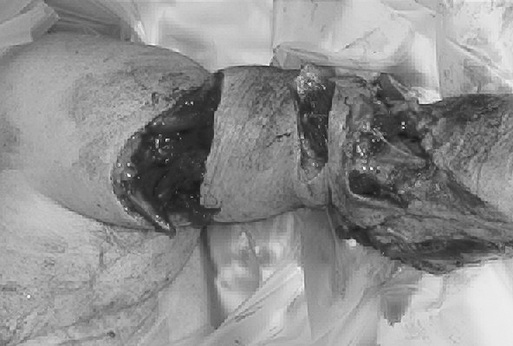

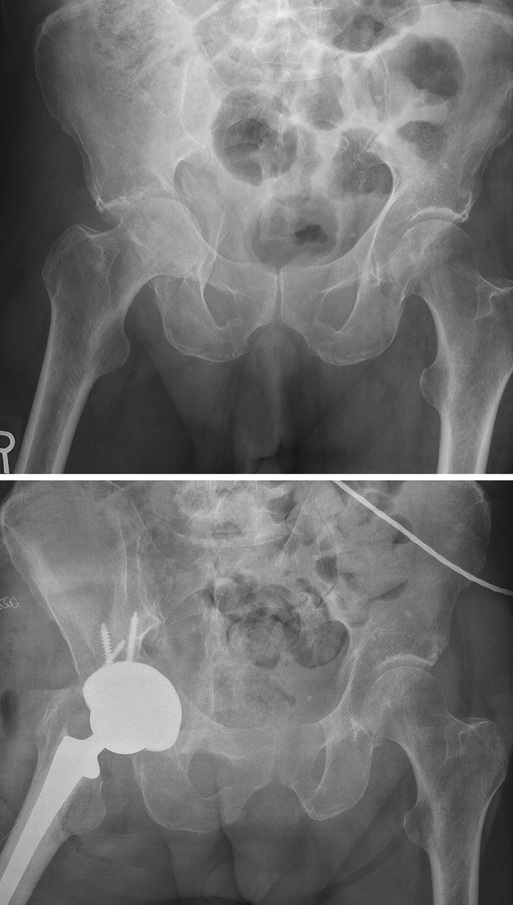

Robert V. Cantu Orthopedic care of older adults, especially those who are frail, presents unique challenges. Frail patients typically have multiple, interacting problems that affect decisions regarding optimal type and timing of treatment. From a strictly orthopedic point of view, inferior bone density and quality compared to younger patients as well as preexisting joint arthropathies can make fixation of fractures challenging and sometimes makes arthroplasty the favored treatment for articular fractures. Increasing evidence suggests coordination of care with an internal medicine or geriatric team provides the best outcomes and minimizes complications.1 This chapter addresses many of the challenges the orthopedist faces when caring for geriatric patients. The World Health Organization has defined osteoporosis as a bone mineral density (BMD) value of 2.5 standard deviations or more below the young adult mean.2 Patients with known osteoporosis are at increased risk for fracture; however, the greatest risk factor for sustaining a fragility fracture is having had a previous one. Most patients with a fragility fracture involving the spine, hip, wrist, or proximal humerus, however, do not meet the BMD definition of osteoporosis.3 These findings can make it difficult to discern which patients should receive pharmacologic treatment to prevent the risk of fracture. They also suggest patients who have had a previous fragility fracture should receive treatment for osteoporosis, even if their BMD is not 2.5 standard deviations below the mean. Despite advancements in treatment, osteoporosis afflicts an estimated 323 million people worldwide, and that number is projected to reach 1.55 billion by the year 2050.4 Fragility fractures result in pain, disability, and medical complications and affect as many as 1 in 3 women and 1 in 12 men during their lifetime. Hip fractures alone are projected to afflict 6.3 million people by the year 2050.4 The medical expenses following fragility fractures are substantial; for example, the annual cost in Europe has been reported to be an estimated 13 billion euros.5 The majority of the cost results from hospitalization after the fracture. The patient who sustains a fragility fracture carries up to a 10-fold increased risk of a second fracture compared to a person who has never had one, with the rate of second fracture within 1 year approaching 20%.6,7 Despite this risk, many patients who have sustained a fragility fracture are not given any preventive treatment. One study found only 7% of patients admitted with a fragility fracture were receiving osteoporosis treatment, and this number increased only to 13% at the time of discharge.4 At a minimum, patients who suffer a fragility fracture should be placed on calcium and vitamin D treatment and consideration given to further pharmacologic treatment. An often overlooked part of treatment is a formal gait and balance assessment in physical therapy. Patients who already have difficulty with balance and strength will have even more trouble while recovering from a fracture. Difficulty with gait and balance likely contributes to the high rate of a second fracture within 1 year of the first. Osteoporosis has a dramatic effect on fracture fixation. Traditional nonlocked plates and screws may not achieve adequate purchase in osteoporotic bone. Locked plates or intramedullary nails should be considered to improve fracture fixation and maintain alignment.8 Bone cement can be used to augment screw fixation, but care must be exercised to prevent extravasation into soft tissues or into the fracture site. Use of allograft bone struts can help provide increased rigidity to fracture fixation. For some fractures, arthroplasty may provide the best treatment and allow earlier weight bearing and mobilization. Several authors have looked at whether it is cost-effective to screen for osteoporosis and initiate pharmacologic treatment before the onset of a fragility fracture.9–12 A study in Australia enrolled 1224 women 50 years and older and categorized them by age group. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scanning was performed on all women and the percentage with osteoporosis was 20% in the 50- through 59-year age group, 46% in the 60- through 69-year age group, 59% in the 70- through 79-year age group, and 69% for those older than 80 years. It was estimated that if all women older than 50 years of age were started on antiresorptive medication, the risk of fracture would decrease by 50% in those with osteoporosis and by 20% in those without osteoporosis. The cost per fracture averted in the 50- through 59-year age group was $156,400, whereas in the older-than-80 age group it was only $28,500. It was concluded that treating all women older than age 50 with antiresorptive medication was not financially feasible. The authors concluded that instituting antiresorptive medication in women older than 60 years with osteoporosis would decrease fractures by 28% and was cost-effective.13 Although people age 65 and older represent approximately 12% of the population in the United States, they account for 28% of all fatal injuries.14,15 This segment is also the fastest growing age group. The fact that older trauma patients often are frail can make their treatment more challenging.16 Cardiopulmonary disease is one of the most common comorbid illnesses and can limit a patient’s ability to tolerate surgery and participate in rehabilitation. Neurologic disorders, such as Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease, are also common and affect mortality rate after injury. Some patients may have residual weakness or contractures from a previous cerebrovascular accident. Any of these disorders can affect gait and balance and limit a patient’s ability to comply with weight-bearing restrictions. Endocrine disorders, particularly diabetes, are common in older patients. Diabetic patients often have vascular compromise secondary to small vessel disease and are immunosuppressed. Nonoperative treatment of select fractures may be preferred in these patients, particularly if there is a preexisting diabetic ulcer near the planned operative field. For multiply injured older adult patients, the injury severity score (ISS) may underestimate the degree of injury and the patient’s ability to tolerate it and generally is a poor predictor of mortality.17 Older adult patients may have a lower ISS than young adults but still be unstable or “in extremis,” in the sense that minimal further insult could tip them past the point of recovery. At the same time, failure to stabilize fractures that are causing blood loss and pain may also result in further deterioration. It is this fine line the orthopedic trauma surgeon must walk when treating older patients with multiple fractures. In such cases, simple splinting or external fixation of upper extremity fractures and external fixation of lower extremity fractures may represent the best initial treatment. Few studies have focused specifically on the impact of orthopedic injuries on older trauma patients.18–22 One retrospective, multicenter study attempted to define factors associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates in older adult patients who had sustained major trauma.18 Of 326 patients with an average age of 72.2 years, there was an overall mortality rate of 18.1%. Of patients who required fracture stabilization, 77% had this done within 24 hours of admission. The mortality rate for patients who underwent fracture fixation within 24 hours was 11% and for those who had fixation after 24 hours it was 18%, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.18 The three complications with the highest mortality rates were acute respiratory distress syndrome (81%), myocardial infarction (62%), and sepsis (39%). For older adult patients with a mangled extremity, early amputation should be considered. Older patients may not be able to withstand the multiple surgeries required to salvage severe open fractures, especially those with vascular insult. If a severely injured limb becomes infected, the cascade of sepsis and multiple system organ failure can proceed quickly. Although it can be a difficult decision, early amputation in an older patient with a mangled extremity can be a life-saving procedure (Figure 71-1). Pain management is an important part of orthopedic care in older adults. Early stabilization of fractures is one aspect of pain control that can aid in minimizing narcotic requirements and, in turn, improve respiratory status and mental status. Patients with stabilized fractures can also obtain an upright posture more easily, be weaned from ventilators, and have less delirium; these factors are all critical for survival in older adults. Selective use of nerve blocks or catheters for continuous infusion, such as a femoral nerve block catheter following a femur fracture, can greatly aid in pain relief and minimize narcotic requirements. Whether spinal or general anesthesia is best for patients with hip fracture remains a matter of debate. A recent retrospective database study of 73,284 patients showed no significant difference in in-hospital mortality, with rates of 2.1% for regional anesthesia and 2.2% for general anesthesia.23 It is possible that particular patients, such as those with advanced pulmonary disease, may benefit from regional anesthesia. Similarly, for patients with advanced cardiac disease, spinal anesthesia may pose a risk because of the potential for resultant hypotension. When hypotension occurs after spinal anesthesia, it is typically a result of a drop in systemic vascular resistance and not a drop in cardiac output.24 An important part of the debate about anesthetic technique, especially for frail older adults who are at increased risk, is the relationship between the type and depth of anesthesia and the occurrence of delirium.25,26 Although postoperative delirium has long been recognized as a problem, it is commonly not measured as an adverse outcome of surgery, something that is likely to change as the growth in the number of older adults will require that care protocols become better suited to their needs.27,28 Part of the preoperative evaluation for many hip fracture patients includes a cardiac risk assessment. For some patients, this results in the acquisition of a transthoracic echocardiogram. In a recent retrospective review of 694 consecutive hip fracture patients, 131 (18.9%) underwent preoperative echocardiogram. It is interesting that no significant difference in mortality was found in-hospital, at 30 days, or at 1 year after surgery between patients who had the echocardiogram and those who did not. None of the patients who had the echocardiogram went on to angioplasty or stent placement. There was a significant difference between the two groups in average time from admission to surgery at 34.8 hours (no echocardiogram) and 66.5 hours (echocardiogram). Length of hospital stay was, on average, 2.24 days longer among the patients undergoing preoperative echocardiogram.29 Treatment of periarticular fractures in older adults often differs from treatment in younger patients. Certain fractures involving the shoulder, elbow, hip, and knee may fare better with arthroplasty rather than open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) in older adults. Several studies have compared ORIF to arthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures in older adults.30–32 The complication rate for those patients undergoing ORIF, including the need for revision surgery, is substantially higher than it is for the arthroplasty group. Controversy exists as to whether hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty is the best treatment. Some studies seem to favor total joint arthroplasty.33,34 Dislocation rate is higher, however, with total joint arthroplasty, especially in patients with dementia, with neurologic disorders such as Parkinson disease, or with hemiparesis after a stroke. Comminuted distal humerus fractures in older adults also may have better outcomes with arthroplasty than with ORIF. Frankle and colleagues reported on 12 patients who underwent ORIF and 12 who underwent total elbow arthroplasty for distal humerus fractures.35 The total elbow arthroplasty group performed better on the Mayo Elbow Performance Score with 11 excellent and 1 good, compared to 4 excellent, 4 good, 1 fair, and 3 poor in the ORIF group. Müller and coworkers reported on their results with 49 distal humerus fractures in patients older than 65 years treated acutely with total elbow arthroplasty.36 Inclusion criteria included patients who were “high compliance” and “low demand.” Average range of motion at follow-up (average 7 years) was an arc from 24 to 131 degrees. A total of five revision arthroplasties were performed during the follow-up period. The authors concluded that the procedure is recommended when the appropriate inclusion criteria are met. For periarticular fractures treated with ORIF, the advent of locked plates has allowed for improved fixation, especially in patients with osteoporotic bone. In one retrospective review of 123 distal femur fractures treated with the less invasive surgical stabilization (LISS) system, 93% healed without bone graft, the infection rate was 3%, and there was no loss of distal fixation.37 In a prospective study of 38 complex proximal tibia fractures treated with the LISS system, 37 of 38 healed with satisfactory alignment, there were no infections, and the average lower extremity measure score was 88.38 Another review of 77 proximal tibia fractures treated with LISS showed 91% healed without complication.39 The overall union rate was 97% with an average time to full weight bearing of 12.6 weeks and an infection rate of 4%. Acetabular fractures are challenging to treat at any age. Helfet and associates were one of the first surgeon groups to report on ORIF of acetabular fractures in older adults.40 In their review of 18 patients age 60 or older followed for 2 years after surgery, the mean Harris hip score was 90 points. All fractures healed and only one patient had a loss of reduction. Complications included two pulmonary emboli and one missed intraarticular fragment requiring reoperation. The authors concluded that “open reduction and internal fixation of selected displaced acetabular fractures in older adults can yield good results and may obviate the need for early and often difficult total hip arthroplasty.”40 More recent work has supported primary total hip arthroplasty for select acetabular fractures in older adults41 (Figure 71-2). To perform arthroplasty in the acute setting may require internal fixation of the fracture to provide enough stability to hold the arthroplasty. Mears and Velyvis have reported their results with this approach in 57 patients with a mean follow-up of 8.1 years and a mean age of 69 years.41 The mean Harris hip score was 89, and 79% of patients had a good or excellent outcome. The authors concluded that this approach is a viable option for patients with a low likelihood of a favorable outcome with fracture treatment alone.

Orthopedic Geriatrics

Introduction

Osteoporosis

Geriatric Trauma

Anesthetic Considerations

Periarticular Fractures

Orthopedic Geriatrics

71