and Paul Telfer2

(1)

Department of Haematology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

(2)

Department of Haematology, Royal London Hospital, London, UK

Introduction

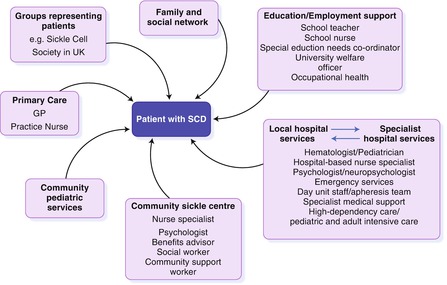

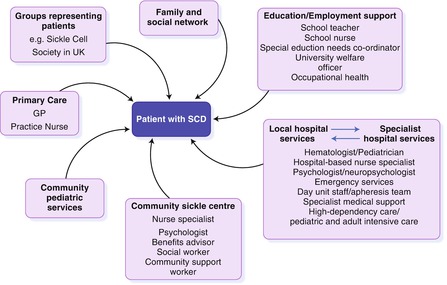

In common with other long-term conditions, sickle cell disease presents a variety of clinical, psychological and social challenges for the patient and his/her carers. When organising services (Fig. 3.1), it is important to consider several particular features of the condition:

Figure 3.1

Components of the care network for a child or adult with SCD

1.

It is highly variable in clinical severity

2.

The natural history entails an accumulation of long-term complications, punctuated by frequent, unpredictable episodes of acute illness

3.

In England, other Northern European countries and North America, it is mainly restricted to ethnic minority groups, particularly black African and Caribbean populations.

The usual model for care requires a team of specialist medical and nursing practitioners interacting with a range of other professionals. The majority of care could be delivered from a community base, but in practice this has been difficult to achieve. Further studies to evaluate different methods of health care delivery are needed.

Hospital-based care is essential for management of acute complications, day care interventions such as transfusion and exchange transfusion, specialist clinic appointments and for laboratory and radiological investigations. Examples of care that could be based either in the hospital or the community include routine out-patient appointments and annual reviews, monitoring of hydroxyurea and iron chelation therapy and management of some chronic complications, such as leg ulcers and chronic pain. Psychological support and social care, liaison with schools, employers, welfare benefit and housing officers are probably best delivered from a community setting.

The current model of care as described in UK national guidelines and supported by the National Hemoglobinopathy Screening Programme and Specialist Commissioning is based on a clinical network co-ordinated by a Specialist Center in a large hospital, which supports local hospital-based centers and community centers in their region. This model will hopefully encourage equitable, accessible and high quality care in low and high prevalence areas.

Specialist Centers

As well as providing specialist services the specialist center is responsible for annual review of all patients, management of complex acute and chronic complications, harmonization of treatment protocols and referral pathways, gathering and reporting of health outcome data, co-ordination of staff education, audit of on-going practice and for co-ordinating research including basic science and clinical trials.

Local Hospital Centers

In high prevalence areas, local centers may manage very large numbers of patients and have an established team of specialist doctors and nurses. In low prevalence areas, the numbers of patients may be very few and resources and skills correspondingly limited. In each case, the objectives of the local center should be the provision of routine care at a high standard, close to the patient’s home, with good communication and agreed referral pathways to the specialist center. Routine care includes management of uncomplicated acute crises, administration of regular transfusions, and routine out-patient care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree