Indicated disease

Conditions

MCN

<4 cm without mural nodules

IPMN

Branch duct type

Asymptomatic

No elevation of CA19-9

Cyst size over 2 cm

No mural nodules

SPN

Well-demarcated small mass

PNET

Nonfunctioning

Functioning

Asymptomatic and ≤2 cm

Small tumors without vascular involvement

Metastatic tumors

Renal cell carcinoma

Colorectal cancer

Melanoma

Sarcoma

28.2.1.1 Candidates in MCN

MCNs are typically detected in pancreas tail of women in their fourth to fifth decade. They may be easily detected on CT or MRI scans as cystic mass. They usually present as unilocular or multilocular cystic mass without evidence of connection to the main duct of pancreas. If the size of MCN is less than 4 cm without mural nodules, organ-preserving pancreatectomy may be considered [5–7]. Large MCNs and MCNs with nodules harbor risk of malignancy and thus should be precluded from undergoing organ-preserving pancreatectomy

28.2.1.2 Candidates in IPMN

It is well known that IPMNs undergo adenoma-to-carcinoma progression. The frequencies of malignancy vary according to the morphological types. The malignancy frequency is reported to be around 60% for the main duct-type IPMN, and standard resection is recommended for all main duct-type IPMN [7]. On the other hand, the branch duct-type IPMNs are more complicated. Their mean malignancy frequency is 17.7%. Thus, not all branch duct-type IPMNs are indicated for operation, and only those at high risk for malignancy are indicated for surgery which is constantly controversial [7]. According to the International Consensus Guideline, organ-preserving pancreatectomy may be considered for branch duct-type IPMN without clinical, radiologic, cytopathologic, or serologic suspicion of malignancy [7]. Asymptomatic patient without elevated tumor markers whose IPMN is over 2 cm and without mural nodule on image studies may be a candidate for organ-preserving pancreatectomy.

28.2.1.3 Candidates in SPN

SPN is seen predominantly in young women and is an indolent tumor with malignant potential. About 15% of resected cases show malignant features but death resulting from SPN is rare [8, 9]. Malignancy predictive factors differ among investigators, and most of them are histological features which can be determined only after resection. Thus, a compromised indication for organ-preserving pancreatectomy may be well-demarcated small SPNs without metastasis.

28.2.1.4 Candidates in PNET

The indication of organ-preserving pancreatectomy in PNET is an ongoing debate. PNETs are usually graded using the World Health Organization (WHO) system which grades PNETs based on Ki-67 and mitotic count [10]. The WHO grade is the most consistent predictive factor for malignancy [11]. But this grade can be obtained after surgical removal of the tumor and cannot be used to establish treatment strategy preoperatively. There are several reports indicating that small size is a predictive factor for either malignancy or high WHO grade [12–17]. Despite ongoing controversies, size is often used to determine treatment strategy. For nonfunctioning PNETs, the most often referenced indication for organ-preserving pancreatectomy is asymptomatic small (≤2 cm) PNETs [18]. For functioning, small tumors especially insulinoma without vascular involvement may be a candidate [4].

28.2.2 Metastatic Tumors

Metastasectomy is known to have benefit for some cancers. Metastatic colorectal cancer, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, neuroendocrine cancers, renal cell cancers, and sarcomas are some of the representative cancers that benefit from metastasectomy. The role of metastasectomy for metastasis to pancreas is yet unknown. And given the rarity of pancreatic metastases, it will be very difficult to analyze the benefit of metastasectomy in pancreatic metastases. The most common pancreatic metastasis is renal cell carcinoma consisting about 60% of all reported pancreatic metastases. Others in literatures include colorectal cancer, melanoma, and sarcoma [19, 20].

The guidelines from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer’s Genito-Urinary group on the management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma recommended metastasectomy in all possible cases for clinical benefit without reference to the site of metastasis [21]. Although there is no concrete evidence to demonstrate benefit of metastasectomy in pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma, the consensus from most of the articles is that patients with renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas benefit from resection [19].

Metastasectomy of colorectal cancer pancreas metastasis demonstrated comparable survival outcome to metastasectomy of colorectal cancer liver metastasis [20]. For melanoma, given the improved survival with metastasectomy in other gastrointestinal sites, pancreatic metastasectomy should also be considered for resection [20].

28.3 Types of Organ-Preserving Pancreatectomy (Table 28.2)

28.3.1 Enucleation

Although the actual history may be older than the reported history, the first enucleation of pancreas was reported in 1898 by Ernesto Tricomi in Italy [24]. The biggest advantage of enucleation is that pancreatic parenchyma can be preserved as much as possible, and other organs such as pancreas need not to be sacrificed. For enucleation to be possible, there are several conditions that need to be met:

- 1.

The lesion needs to be determined as benign or low-grade malignant neoplasm during preoperative evaluation.

- 2.

Signs of malignancy such as vascular involvement or infiltration of other organs must be absent.

- 3.

No evidence of distant metastasis demonstrated at preoperative images.

- 4.

Sufficient distance from the main pancreatic duct must be secured.

Table 28.2

Summary of organ-preserving pancreatectomy in lesions without evidence of malignancy

Operation | Location | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

Enucleation | Anywhere | 2–3 mm distance from the main pancreatic duct |

DPPHR | Head | Preservation of posterior arcade of PD vessels |

PHRSD | Failed DPPHR due to margin or ischemia | |

Ventral pancreatectomy | Head | Limited to uncinate process |

Pancreas head excavation | Head | Limited to pancreas head |

Preservation of vasculature | ||

Central pancreatectomy | Neck and proximal body | Adequate proximal and distal margin |

Preservation of splenic vessels | ||

Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy | Body and tail | No evidence of malignancy |

Sufficient distance from spleen | ||

Middle-preserving pancreatectomy | Head and tail | Multiple lesions in head and tail |

No lesion in body | ||

Dorsal pancreatectomy | Anywhere except ventral pancreas | Multiple lesions anywhere other than ventral pancreas |

Pancreas divisum |

There is no consensus on the absolute value of distance from the tumor to the main pancreatic duct. Distance of at least 2–3 mm is often dictated reference but the evidence is low [25]. Some tips to ensure safety of main pancreatic duct when conducting enucleation include utilizing intraoperative ultrasonography (US) and insertion of pancreatic drainage tube through endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography preoperatively.

Before conducting enucleation, the abdominal cavity should be thoroughly explored to rule out any unexpected discrepancy with preoperative work-up findings such as seeding, distant metastasis, regional lymph node metastasis, or adjacent organ invasion. Any enlarged lymph node should be resected for intraoperative frozen biopsy. If the biopsy turns out to be metastatic lymph node, enucleation should be abandoned and converted to conventional pancreatectomy with standard lymph node dissection.

Intraoperative US is particularly helpful during enucleation. It can identify the targeting lesion and morphology and also evaluate its distance from the main pancreatic duct [26, 27]. In addition, additional multifocal lesions may be incidentally detected during intraoperative US especially in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 1 [28].

When performing enucleation, the most important thing to consider is to remove the tumor completely without disrupting the capsule. Meticulous dissection is essential with ligation of small vessels. When ligating the vessels, any of surgical ties, clips, electrical coagulation device, or harmonic scalpel may be used. However, operator should take caution when using electrical coagulation device or harmonic scalpel, since they may inflict thermal injury to the main pancreatic duct. Drain should be placed and positioned in the proximity of enucleated site to monitor postoperative bleeding or pancreatic fistula.

The enucleated mass should be sent for frozen biopsy to ensure that it is not malignant. If it is found to be malignant, then conventional pancreatectomy needs to be performed. If it is found to be malignant or to have inadequate margin at permanent pathologic report, reoperation should be considered.

The major drawback of enucleation is relatively high incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula. The postoperative pancreatic fistula rate is reported to be around 30% with clinically relevant fistula (i.e., International Study Group on pancreatic fistula grade B and C) rate of 15% [29–31]. However, most of the fistulae are known to resolve without operative intervention. The overall morbidity of enucleation is acceptable compared to the conventional pancreatectomy [32]. Recurrence is rare after enucleation when the patients are carefully selected. More importantly, exocrine/endocrine insufficiency is very low with 0–6% incidence rate [4, 32–34].

28.3.2 Partial Pancreatectomy According to the Location of Target Lesion

28.3.2.1 Head

Pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy may be considered to be “organ”-preserving pancreatectomy in relation to Whipple’s operation. Since the two operative techniques have similar radicality and outcome, these two operations will be regarded as conventional pancreatectomy.

Duodenum-Preserving Pancreatic Head Resection (DPPHR) and Pancreatic Head Resection with Segmental Duodenectomy (PHRSD)

Beger et al. [35] first introduced DPPHR on a patient with chronic pancreatitis and inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas. Since then, various modified techniques have been developed to fit resection of benign or low-grade malignant neoplasms of pancreas head [36, 37]. The potential benefits of DPPHR are the improved quality of life through the preservation of digestive tract and bile duct integrity, and the preservation of whatever amount of pancreas head parenchyma may be possible [38, 39]. While DPPHR may offer more conservative treatment, the procedure is very complex and demanding.

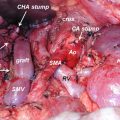

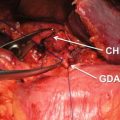

The technique involves division of pancreas over the portal vein and subtotal resection of the pancreatic head. In the process, preserving the posterior arcade of pancreaticoduodenal artery is important to maintain blood flow to the duodenum. The common bile duct is skeletonized semi or full circumferentially according to the amount of pancreatic rim on the duodenum that can be preserved. The remnant pancreas can be anastomosed to Roux-en-Y jejunal loop, duodenum, or posterior wall of the stomach [36, 37, 40].

The reported overall complication rate is estimated to be 46%, ranging from 24% to 55% [39, 40]. Mortality is rare. Although postoperative outcome is acceptable, there are some unique concerns for DPPHR. One is uncertainty of complete excision due to remnant pancreatic rim or main duct. Another is the risk of ischemia of duodenum, ampulla of Vater, and bile duct. Thus preservation of posterior arcade of pancreaticoduodenal artery is essential. PHRSD was devised by Nakao et al. [41, 42] in 1994 to avoid these problems. All pancreaticoduodenal arcades are sacrificed except for anterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery which is needed to supply the third portion of duodenum. Then second portion of duodenum and distal common bile duct are resected along with pancreas head. While PHRSD can save time of vessel preservation, extra time is consumed for additional choledochoduodenostomy and duodenoduodenostomy, resulting in similar operation time with DPPHR. The complication rate of PHRSD is similar to that of DPPHR. Therefore, when risk of ischemia or positive resection margin is concerned with DPPHR, PHRSD may be a reasonable alternative.

The complication rate and postoperative fistula rate of DPPHR and PHRSD are similar to that of pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy [43]. But at the same time, DPPHR and PHRSD offer better exocrine and endocrine pancreatic function [44–46]. Therefore, DPPHR and PHRSD may be performed instead of conventional pancreatectomy in carefully selected indicated patients.

Ventral Pancreatectomy

Ventral pancreatectomy, also known as inferior head resection, was first reported by Takada in 1993 [47]. The uncinate process and pancreatic tissue around the Wirsung’s duct are resected. Kocher maneuver should not be performed in order to preserve small vessels to duodenum. The pancreaticoduodenal arcades are all preserved, and only the branches of inferior pancreaticoduodenal vessels are ligated. Parenchyma is divided so that half of distal common bile duct becomes exposed. After excision of the inferior head of the pancreas, the duct of Wirsung is anastomosed to the third portion of the duodenum in an end-to-side fashion [48].

Although there are not many reports on the outcome of ventral pancreatectomy, a recent report indicated 67% morbidity rate without any mortality. The pancreatic fistula rate was 47%. No impairment in exocrine and endocrine pancreatic function was noted in 15 patients. The efficacy of ventral pancreatectomy still needs further investigation [49].

Pancreatic Head Excavation

Andersen et al. [50] reported this modification of DPPHR in 2004. Proximal pancreatic duct or central core of the pancreatic head is excised using ultrasonic dissection, and longitudinal side-to-side Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy is performed. Analysis of five cases revealed 33% complication rate without mortality [51]. The feasibility remains to be investigated.

28.3.2.2 Neck and Body

Central pancreatectomy is also known as median pancreatectomy, middle pancreatectomy, or middle segment pancreatectomy. This operation was first reported by Guillemin and Bessot [52] in 1957 to treat chronic pancreatitis patient. This operative technique is suitable for lesions located in the neck or proximal body of pancreas which are not amenable by enucleation. Central pancreatectomy allows preservation of the spleen as well as normal pancreas parenchyma. But in order for central pancreatectomy to be done safely and successfully, certain conditions must be met:

- 1.

Possibility of malignancy must be ruled out at preoperative studies.

- 2.

Adequate margins need to be obtained both proximally and distally.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree