BACKGROUND

The standard treatment for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and Type 2 diabetes in pregnancy has been diet therapy, with the addition of insulin when blood sugar targets are not achieved. In the 1970s and early 1980s oral hypoglycemic agents gained usage in pregnancy, particularly in South Africa. However, this trend failed to gain popularity as experts in the field cautioned against their use because of fear of teratogenicity, and reports of pro-longed neonatal hypoglycemia. In spite of these concerns, a growing body of literature has been accumulating on the use of oral agents in pregnancy. In this chapter we examine the evidence for the safety and efficacy of oral hypoglycemic agents in women with GDM, PCOS, and Type 2 diabetes in pregnancy.

SULFONYLUREAS AND MEGLITINIDES

Sulfonylureas and meglitinides are “insulin secretagogues” (Table 11.1). They both bind to receptors (although not at identical sites) on the pancreatic beta cell, causing insulin secretion. Examples of sulfonylureas include the first-generation sulfonylureas, tolbutamide, chlopropra-mide, and tolazamide, and the second-generation sulfonylureas, such as glyburide (glibenclamide), glipizide, and glimeperide. The meglitinides include nateglinide and repaglinide.

Table 11.1 Properties of oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs).

| Type of OHA | Examples | Mechanism of action |

| Sulfonylureas | First generation: tolbutamide, chlopropramide and tolazamide Second generation: glyburide or glibenclamide, glipizide and glimeperide | Insulin secretagogue: bind to the sulfonylurea receptor on the beta cell of the pancreatic islets, leading to closure of the ATP sensitive potassium channel, leading to insulin secretion |

| Meglinitides | Nateglinide and repaglinide | Insulin secretagogue: bind to a receptor close to the sulfonylurea binding site on the beta cell, causing closure of the ATP sensitive potassium channel, leading to insulin secretion |

| Biguanides | Metformin | Reduce hepatic glucose output, increase peripheral glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and adipocytes, and reduce intestinal glucose absorption |

| Glucosidase Inhibitors | Acarbose and voglibose | Slow carbohydrate absorption and reduce postprandial glucose by inhibiting the alpha-glucosidase enzymes present on the brush border of the small intestine |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma(PPAR-gamma) agonists | Rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, and troglitazone | Insulin sensitizers: bind to the nuclear transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) which modulates gene expression in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and the liver, leading to changes in several metabolic pathways which involve glucose transport, lipoprotein lipase, and insulin signaling |

Placental transfer

In light of earlier reports of neonatal hypoglycemia in infants of mothers taking sulfonylureas, researchers investigated whether sulfonylureas crossed the placenta by using the human placental cotyledon perfusion model. In this model, a human placental cotyledon is obtained from a healthy mother at the time of delivery. The drugs in question are perfused on the maternal side, and transfer of the drug is measured on the fetal side. Studies found that, although the first-generation sulfonylureas crossed the placenta in moderate amounts (tolbutamide 21.5% and chlorpropramide 11%), the second-generation sulfonylureas crossed less (glipizide 6.6%), with glyburide crossing the least (3.9%).1 A similar finding was noted in a study using glyburide in women with GDM. Glyburide was measurable in the serum of these women at the time of delivery; however, no glyburide was detected in cord blood.2 There are no studies to date looking at the placental transfer of the meglitinides.

Clinical experience: cohort studies and randomized trials

Congenital anomalies

Women with Type 2 diabetes

The majority of studies looking at the rate of congenital anomalies in women using sulfonylureas in the first trimester have not shown an increased rate of congenital anomalies.3–6 Only two studies found an increased rate (n = 20 and n = 43, respectively); however, glycemic control was either not ideal7 or not described.8 A meta-analysis of 471 women exposed to oral agents (sulfonlyureas and/or biguanides) in the first trimester compared with 1344 women not exposed, found no significant difference in the rates of major malformations.9 In the largest retrospective cohort study to date (n = 342), congenital anomalies were associated with poor glycemic control rather than the specific oral hypoglycemic agent (OHA) used (glyburide/glibenclamide or met-formin).3 In summary, sulfonylureas are unlikely to be teratogenic.

There are limited data on congenital anomalies with meglitinide use, but two recent case reports of three women exposed to repaglinide during the first trimester of pregnancy did not report any congenital malformations.10,11

Perinatal mortality

Women with Type 2 diabetes

In early cohort studies of women with Type 2 diabetes in pregnancy, treatment with either sulfonylureas alone, or in combination with metformin, resulted in reduced rates of perinatal mortality when compared with those who were “untreated”. However, perinatal mortality rates were higher than those in women who were converted verted to insulin. This was attributed to better glycemic control in those treated with insulin.4,5,12 In a more recent retrospective cohort study by the same group in South Africa, the use of OHAs throughout pregnancy (glyburide [glibenclamide] alone, or in combination with met-formin) was associated with an increased rate of perinatal mortality.3 However, there were no perinatal deaths in infants of women taking metformin exclusively. The perinatal mortality rate was significantly higher in the group that used OHAs throughout compared with those who switched to insulin at the beginning of the pregnancy, or those who were treated with insulin alone. This could not be explained by differences in glycemic control, maternal age, body mass index (BMI), parity, booking gestational age or comorbidities between groups. The reason for this increased rate of perinatal mortality is unclear but until more definitive data are available, the use of insulin is preferred in women with Type 2 diabetes. Other studies, some of higher quality (randomized controlled trials) in women with gestational diabetes, have not found this association (see below).2

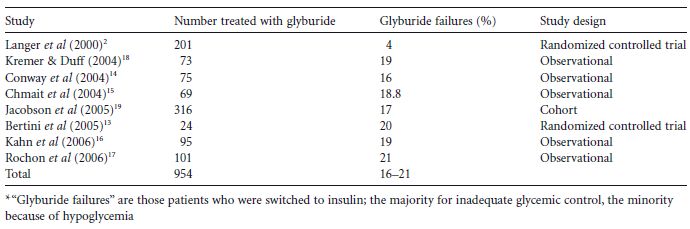

Table 11.2 Glyburide failure rates* in women with gestational diabetes.

Other morbidity

Women with gestational diabetes mellitus

In 2000, Langer and colleagues conducted a landmark randomized controlled trial involving 404 women with GDM.2 Those women who failed to meet targets on diet were randomized at 11–33 weeks of gestation to receive either insulin or glyburide therapy (starting at 2.5 mg in the morning and titrated to 20 mg/day when necessary). They found no significant differences in glycemic control or neonatal outcomes between the two groups, including large birthweight for gestational age (LGA), macrosomia, birthweight, neonatal hypoglycemia and pulmonary complications, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), congenital anomalies or perinatal mortality. Eight patients (4%) in the glyburide group needed insulin. While this study was groundbreaking, one of the main criticisms was that it was underpowered to assess neonatal outcomes. Since publication of this trial there has been only one other very small randomized trial (<30 women per arm), where women with GDM were randomized to glyburide, insulin or acarbose.13 No difference was found in glycemic control or birthweight, although there were significantly more infants with neonatal hypoglycemia in the glyburide group.

Several observational studies have been published looking at how often GDM women treated with glyburide need to be switched to insulin (i.e. “glyburide failure”).14–17 In these studies glyburide “failure rates” ranged from 16% to 21% (Table 11.2), the majority being because of poor glycemic control and a minority because of hypoglycemia. Predictors of “failure” included a glucose challenge test result greater than or equal to 11.1mmol/L (≥ 200 mg/dL), diagnosis before 25 weeks, increased maternal age, multiparity, and pretreatment fasting capillary blood glucose values of greater than 6.1mmol/L (> 110 mg/dL). Target values in these studies were fasting values of 5.0-5.3 mmol/L (90-95 mg/dL), 1-hour values of 7.2-7.8mmol/L (130-140mg/dL), and 2-hour values of 6.4–6.7 mmol/L (115-120mg/dL).

There are no data on the use of glipizide or the meg-litinides in women with gestational diabetes or Type 2 diabetes.

Use of sulfonylureas during pregnancy: summary and existing concerns

Glyburide (glibenclamide) does not appear to be teratogenic, nor does it cross the placenta to an appreciable extent. In women with Type 2 diabetes there is some concern regarding increased perinatal mortality with continued use of glyburide throughout pregnancy, and until further studies are available, women should be switched to insulin during pregnancy. In women with GDM, glyburide is associated with good glycemic control in the majority, with failure rates of approximately 16–21% (Table 11.1). Most studies found no differences in neonatal outcomes between women on glyburide and those using insulin. However, because there is only one randomized controlled trial of moderate size that was not powered to assess neonatal outcomes, some concerns remain.

METFORMIN

Metformin is a biguanide which acts by reducing hepatic glucose output, increasing peripheral glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and adipocytes, and reducing intestinal glucose absorption (Table 11.1). This leads to improved insulin sensitivity. It does not cause insulin secretion and hence does not cause hypoglycemia or weight gain. It is contraindicated in patients with renal dysfunction or abnormal creatinine clearance from any cause.

Placental transfer

Metformin freely crosses the placenta. This was demonstrated in a placental transfer study which showed that metformin transferred readily from the maternal to the fetal side of placentas from women with GDM.20 Two studies throughout preg nancy found that levels were 50–100% as high as maternal blood concentrations, and in some infants the level was even higher.21,22

Clinical experience: cohort studies and randomized trials

Ovulation induction, pregnancy, and live birth rates

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome

Metformin has been shown to decrease insulin resistance in women with PCOS, which has resulted in improved rates of ovulation.21

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree