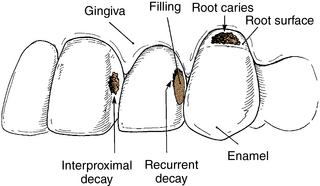

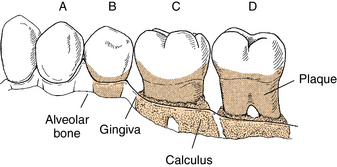

53 Common Oral Problems in Older Adults Low Utilization of Dental Services Need for Oral Health Screening Preventing Infective Endocarditis Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Relate the risk of poor oral health to systemic health. • Explain the increased susceptibility of older adults to dental caries and periodontal disease. • Discuss the clinical significance of mouth dryness and its causes. • Name the indications for immediate referral to a dentist. • Describe the guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in cardiac patients at risk for infective endocarditis and in patients with total joint replacement. • List the major risk factors for oral cancer, its sites, and its public health significance. Oral disease can be detrimental to systemic health, particularly in the medically compromised elderly. Older adults with oral problems have shown insufficient consumption of important vitamins and lower Healthy Eating Index scores.1 Poor oral health affects chewing, speaking, and swallowing, as well as self-image, self-esteem, and socialization. Much research suggests poor oral health contributes to systemic disease. Periodontal disease has been shown to increase the risk for poor glycemic control in patients with diabetes (increasing the risk sixfold).2 Diabetes patients who received treatment for their periodontal disease showed a significant improvement in HbA1c levels (p = .04).3 Periodontal disease may also increase the risk for cardiovascular or renal complications in those with diabetes.4 Multiple studies report poor oral health contributes to development of respiratory disease.5–8 In individuals with poor oral hygiene, bacteria are released from plaque into the saliva and may be aspirated into the lungs, precipitating bacterial pneumonia.9 A systematic review found good evidence that improved oral hygiene and professional oral health care decrease the risk of respiratory disease in frail elders who are residents in long-term care facilities (relative risk reduction of 34% to 83%).10 In April of 2012, the American Heart Association (AHA) released a statement after review of more than 500 peer-reviewed papers investigating potential linkages between periodontal disease and atherosclerotic diseases. The conclusion of the AHA was that there is no evidence that periodontal disease is a causative factor for atherosclerotic disease.11 Regarding the benefit of periodontal therapy to improve outcomes in patients, the authors state: “Although periodontal interventions result in a reduction in systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in short-term studies, there is no evidence that they prevent ASVD [arteriosclerotic vascular disease] or modify its outcomes.”11 More research is necessary to fully understand the role oral health plays in cardiovascular health. Evidence suggests that osteoporosis is associated with periodontal disease, specifically loss of alveolar bone that surrounds the teeth.12 Further, bisphosphonates prescribed to treat osteoporosis may predispose dental patients to osteonecrosis, a condition that results in necrosis of the jaw bone often accompanied by exposed bone, pain, infection, swelling, and dysethesias.13 To help prevent osteonecrosis, physicians should collaborate with the patient’s dentist to inform the patient of risks and ensure optimum oral health before prescribing bisphosphonates. Excellent oral hygiene, regular professional dental cleanings, and appropriate timing for oral surgical procedures may minimize the risk of osteonecrosis.13 Dental caries (decay) is the progressive destruction of tooth structure caused by acids produced by sugars and bacteria in the oral cavity (Figure 53-1). If untreated, dental caries can progress into the pulp of the tooth, causing pain and a dental abscess, which may lead to bacteremia, facial/pharyngeal infection, septicemia, and in rare cases cavernous sinus thrombosis. Figure 53-1 The most common form of dental caries in older adults is root caries: decay that attacks the portion of the tooth not protected by enamel, that is, the root. Root caries may appear as a tan, brown, or black discoloration in this area or as frank cavitation. Recurrent caries develop adjacent to a filling at its margin. Interproximal caries occur between teeth and may not be observed clinically. Because an increasing number of adults are retaining their teeth throughout their lifetime, dental decay is increasing in the elderly. Nearly one third of older adults have dental caries, averaging one new carious surface per person per year. Decay in elders is more likely to go untreated; elderly have four times the mean number of untreated carious surfaces compared to U.S. schoolchildren.14 Approximately 86% of adults older than age 65 experience recession (gums pull away from the teeth). This is not a normal part of aging but instead is caused by periodontal disease or trauma from overzealous toothbrushing. Tooth roots are exposed by recession, and cementum, which covers the roots, is more susceptible to decay than enamel. Elders are therefore more prone to root caries than their younger counterparts.15 In fact, root caries is the most common type of decay in elders. A study of community-dwelling elders found 52% had a history of root caries and 22% had active untreated root caries.16 This type of decay progresses rapidly and will amputate the tooth at the gum line if untreated. A diet high in carbohydrates is a major risk factor for dental decay. Declines in cognitive and physical function impair the ability to brush and floss one’s teeth and increase the risk of decay. Institutionalized elders may experience 3 times the prevalence of decayed teeth compared to community living older adults.17 Dry mouth, often induced by medications, is another important risk factor for caries. Decayed teeth in older adults are generally less symptomatic than in younger adults. Active decay has a yellowish brown color. Early root decay appears broad and shallow. Decay on the crowns of teeth is usually found around preexisting fillings or crowns (see Figure 53-1). Dental radiographs and transillumination are helpful in diagnosis. Periodontal disease is caused by bacteria in dental plaque. Failure to effectively remove plaque by proper oral hygiene and professional cleanings results in an accumulation of plaque and calculus (mineralized plaque) that induces inflammation and infection of the gingiva and alveolar bone (Figure 53-2). Other risk factors include smoking, diabetes, osteoporosis, osteopenia, genetics, and hyposalivation. Figure 53-2 The periodontium consists of alveolar bone and gingiva, the anatomic foundation for sound teeth (tooth A). Healthy periodontium is maintained by thorough oral hygiene practices. When plaque remains on teeth, gingivitis develops (tooth B). The accumulation of plaque and calculus on teeth results in destruction of the periodontium known as periodontitis (tooth C). Periodontitis is considered severe when more than 50% of supporting bone has been lost (tooth D). Early periodontal disease is characterized by redness, bleeding, and edematous gingival tissues. As the disease progresses, bone surrounding the teeth is destroyed (see Figure 53-2). As a result, teeth become mobile. Diagnosis of periodontal disease involves measuring the depth of the periodontal pockets with a probe and radiographic examination to determine if bone loss has occurred. The entire oral cavity, including teeth, needs to be examined to determine the extent of periodontal disease. Xerostomia (the patient’s subjective complaint of mouth dryness) and hyposalivation (the objective reduction in salivary secretion) are correlated and prevalent problems in older adults. Approximately 30% of adults 65 and older suffer from xerostomia.19 Saliva is essential to maintain oral and general health. Dry mouth reduces comfort and quality of life. Constant mouth dryness may reduce compliance with prescription medications; patients may alter dosage or stop the drug altogether. It may also restrict dietary choices and compromise nutrition by making chewing and swallowing uncomfortable, altering taste, and diminishing food enjoyment. Lack of adequate salivation is associated with chronic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).20 Dry mouth increases the frequency and severity of dental caries. There is often rampant, rapidly progressive decay that is difficult to manage and more substantial periodontal disease in individuals suffering from mouth dryness. Also the patient’s ability to tolerate a denture is compromised because of lack of lubrication of oral tissues. Salivary flow does not decline with age; medical conditions and their treatment, rather than age, are associated with mouth dryness. The most common cause of hyposalivation is medication use. Many drugs used to manage issues in older adults contribute to oral dryness; these include sedatives, antipsychotics, antianginal agents, antidepressants, antihistamines, antihypertensives, antiparkinson agents, diuretics, and anticholinergics. Sjogren’s syndrome is the most common salivary gland disorder in the elderly leading to xerostomia. Reduced saliva may also be a result of patient dehydration or salivary duct obstructions such as sialoliths, infections, tumors, head and neck radiation, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease.21 In many cases topical treatment using a saliva substitute may be helpful. Over-the-counter saliva substitutes include Oral Balance gel (Laclede products) and Mouthkote (Unimed). Salivary stimulants such as sugarless Biotene Xylitol gum (Laclede Products) and sugarless candy may also be helpful. Systemic salivary stimulants (pilocarpine) may be used, especially in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome, but should be avoided in those with glaucoma or pulmonary disease. Patients should be encouraged to drink plenty of water and avoid alcohol and caffeine.22 In the 1950s half of all Americans older than age 65 had lost all of their natural teeth.23 Today the edentulism rate of older adults has decreased to 18%.24 The downward trend in edentulism is largely the result of fluoridation of community water, increased education about prevention of oral disease, and increased access to dental care. Adverse outcomes of edentulism include difficulty chewing and speaking, poor esthetics, and lowered self-esteem. A recent study found 45% of denture wearers have oral lesions caused by their denture.25 Regular dental care is essential for maintaining the functional benefits of dentures and the health of the edentulous mouth. Dental caries and periodontal disease are the main determinants of tooth loss leading to edentulism. Comorbidities of edentulism include poor nutrition, smoking, diabetes, coronary artery plaque, and rheumatoid arthritis.26 Risk factors for edentulism include poverty and fewer than 12 years of education in non-Hispanic white people (but not in black or Mexican-American people),27 lower original intelligence,28 and increasing age.29 Complete dentures are the mainstay of treatment for restoring the edentulous mouth. Dentures are not fitted “for life”; they will get looser with time and need regular professional attention. The edentulous ridge (remaining alveolar bone) undergoes continuous resorption over the years, ultimately compromising the fit and stability of the dentures. Only 13% of denture wearers seek annual dental care, and nearly half have not seen a dentist in 5 years.30 Dental-implant–supported dentures may provide more functional capacity than less costly conventional dentures but not every patient is an implant candidate. Estimates from the American Cancer Society indicated that more than 36,000 individuals would be diagnosed with oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma in 2010.31 Of these cancers, approximately 24,000 would be located in the oral cavity proper, excluding the lower lip vermilion and pharynx. Oral cancer incidence increases with age, with the median age at diagnosis being 61 years. Over the last several decades, the incidence rate for men has declined, but it has remained stable in females. Black males have a 30% higher incidence rate than white males for reasons that are not well understood.32 Despite important advances in the treatment of oral cancer, the 5-year survival rate (approximately 50%) has not changed appreciably in the last 50 years. This is likely related to several factors, the most important of which is the fact that more than 60% of oral cancers are not diagnosed until they are of advanced stage clinically.32

Oral disorders

Oral–systemic linkages

Common oral problems in older adults

Dental caries

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Periodontal disease

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Mouth dryness

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Management

Edentulousness

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Management

Oral and oropharyngeal cancer

Prevalence and impact

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Oral disorders