Background on criminal justice in the United States

In the United States, the rate of incarceration has skyrocketed over the last 50 years, ignited by the “Tough on Crime” as well as the “War on Drugs” political pushes of the 1970s and disproportionately affecting people of color and people with mental health illnesses. The lifetime likelihood of incarceration for black men in the United States is 1 in 3, compared 1 in 17 for white men (Bonczar, 2013). Of the 2.2 million people incarcerated in the United States at any given time, over half have been diagnosed with a substance use disorder, with or without a serious mental illness. 12% of jail inmates report using opioids regularly, more than six times higher than the general population [ , ].

The specifics of mass incarceration based on location, medical care, and jurisdiction should also be highlighted. 1.2 million sentenced individuals are incarcerated in state prisons, while approximately 600,000 people reside in local jails in the United States. Jail stays are generally shorter, tend to be a pretrial population, and are more likely to consist of time served for misdemeanors. Prisons stays, on the other hand, are longer, for sentenced individuals, and generally sentences that involve more serious crimes. In terms of jurisdiction, jails mostly are managed under local governing bodies, while prisons are managed at the state or federal level. Within federal prisons, run by the federal Bureau of Prisons or utilizing private prisons in some places, approximately 200,000 people are currently incarcerated. Drug offense charges comprise 14.8% of sentences at a state level and 47.3% at a federal level [ ]. With more states interested in implementing diversion for low-level offenses like drug possession, these statistics will hopefully change, but again, in the scope of the ongoing “War on Drugs” and the opioid epidemic, there is a real concern that this could continue to worsen.

Prisoners are the only group of people in the United States who have a constitutional right to healthcare. The federal case Estelle v Gamble (1976) determined that prisoners should be guaranteed three basic rights: the right to access to care, the right to care that is ordered, and the right to a professional medical judgment. Any lack of these rights for prisoners constituted a violation of the 8th Amendment, “cruel and unusual punishment” [ ]. Despite a federal ruling, many prisoners still have incomprehensibly poor access to healthcare, and the variability in quality of care is wide.

Bloodborne illnesses in criminal justice settings

As other chapters in this book will delve into the details of bloodborne illnesses in the setting of opioid use disorder, we will focus specifically on the criminal justice setting.

Epidemiology

It is well known that bloodborne illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, HCV, and tuberculosis are more prevalent in criminal justice settings. In terms of prevalence, in 2006, the rate of hepatitis C was 8.7 times higher among those who were incarcerated than the general population (17.4% compared with 2.0%) [ ]. The incidence of HIV and HCV acquisition is also significantly affected by incarceration. Recent incarceration, when compared with nonincarceration, increases the risk of acquiring HIV by an estimated 81% and increases the risk of acquiring HCV by an estimated 62% [ ]. These staggering statistics are important to highlight: individuals leaving correctional facilities are at a tremendous risk of contracting HIV and HCV after release, most commonly through IVDU and sexual exposure.

In addition to bloodborne illnesses being more prevalent in criminal justice settings, people living with HIV/AIDS and HCV are more likely to be incarcerated. In 1997, a study on the infectious disease (ID) burden within United States correctional facilities estimated between 20% and 26% of people with HIV/AIDS passed through prisons and jails, and between 29% and 32% of people with HCV [ ]. Despite a large ID burden, treatment of bloodborne illnesses in correctional facilities is not standardized.

Treatment of bloodborne illnesses in criminal justice settings

The treatment of HIV in correctional settings has long been proven to result in higher rates of viral load suppression and significant increases in CD4 counts [ ]. Providing antiretrovirals in the correctional setting is relatively straightforward given consistent patient access to medications and a highly controlled environment, yet it is also complicated by the difficult and critical matter of maintaining patient confidentiality in an extremely vulnerable and stigmatizing setting and by needing to obtain costly medications that may not be on an institution’s formulary. HIV treatment in correctional settings was pioneered by ID specialists and has been a successful endeavor that should be continued.

Treatment of HCV with direct-acting antivirals during incarceration is currently prohibitively expensive for many facilities but wholly necessary to cure the HCV epidemic. As the population at highest risk for contracting and transmitting HCV is within the community of people who inject drugs (PWID), and PWID are disproportionately incarcerated, the correctional setting is an important if not invaluable place to initiate HCV treatment. Given the increase in HCV transmission postrelease, a plan to treat individuals prior to release is the most effective method to improve health outcomes for the individual as well as reduce continued transmission postrelease. A dynamic mathematical model that examined HCV treatment for the incarcerated in Scotland recently demonstrated not only a reduction in overall HCV burden over a time period of 15 years but projected cost savings for the country due to reduced transmissions, in spite of high costs of treatment upfront [ , ]. Moreover, in the United States, the cost of HCV treatment has the potential to be negotiated effectively, especially in the setting of a large enough purchaser. The US Department for Veterans Administration in 2016, for example, negotiated a drug price cap of $15,000 per person for a treatment course of DAA [ ]. In state correctional systems, similar negotiations are possible. To our knowledge, multiple states so far are utilizing federal 340B drug pricing. Louisiana has negotiated a novel deal with Asegua Therapeutics LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Gilead Sciences, Inc., where for a fixed sum of money, the state will be able to purchase an unlimited amount of Asegua’s authorized generic sofosbuvir/velpatasvir to treat patients within Louisiana’s Medicaid and Department of Corrections populations and caps the State’s medication costs for the next 5 years [ ].

ID specialists may be interested in partnering with correctional facilities to deliver this care in multiple ways. ID specialists may treat patients directly: they can contact medical personnel (information generally available on Department of Corrections websites) to identify current practices in nearby correctional facilities. If an opportunity to provide ID treatment does not already exist in a correctional facility, providers practicing in outpatient settings including community health centers and federally qualified health centers have the ability to initiate a program to treat patients with HIV and/or HCV who are currently incarcerated by utilizing federal 340B drug pricing through their community clinics.

Treatment of bloodborne illnesses after release, ID specialists as referral sites

As noted in the previous section, individuals with HIV/AIDS in correctional settings do generally achieve high rates of viral suppression and significant increases in CD4 lymphocyte counts while incarcerated, but on release, these improvements are not sustained [ , , ]. Intensive case management and provider continuity have been shown to be some of the most effective strategies to engage other vulnerable individuals in care, but no studies to our knowledge have yet demonstrated sustained improvements for justice-involved persons with HIV [ , ]. At this time, we recommend that ID specialists work with public health departments to establish themselves as referral providers for the treatment of communicable diseases of justice-involved individuals.

The duration of effective HCV treatment again should be strongly considered while individuals are serving sentences. For jail settings, however, there can be concern of release prior to HCV treatment completion due to shorter sentences. In this scenario, an ID specialist could meet a patient while incarcerated, initiate workup, and link them to the appropriate care on the outside. This direct linkage has proven to be most effective, as patients prefer continuity of providers.

Medications for addiction (opioid use disorder) treatment

Drug overdoses are now the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of 50. There is a plethora of evidence demonstrating that methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone are all effective treatments for opioid use disorder, with methadone and buprenorphine being superior, and will be referred to as medications for addiction treatment, or MAT, in this chapter.

Methadone is a schedule II narcotic and full opioid agonist, first introduced as a medication to treat opioid use disorder in 1974. Methadone continues to be tightly regulated at a federal level, through opioid treatment programs. Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist and schedule III medication, was approved by the FDA in 2002 for the treatment of opioid use disorders. The benefits of buprenorphine include its ability to be prescribed in outpatient facilities (outpatient-based opioid treatment, or OBOTs), fewer side effects as compared with methadone, and a farlower risk of overdose when compared to other opioids. Administration of buprenorphine to a person who has recently used opioids can precipitate withdrawal given buprenorphine’s high affinity for mu receptors (knocking other opioids off the receptor). As such, buprenorphine initiation necessitates that a person be in opioid withdrawal or completely off opioids, to avoid putting patients in uncomfortable and potentially dangerous situations. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is most effective as a monthly intramuscular injection, but necessitates a longer abstinence from opioids than either methadone or buprenorphine.

Treatment of opioid use disorder in criminal justice settings

Per a recent release by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, “Medication-based treatment is effective across all treatment settings studied to date. Withholding or failing to have available all classes of U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved medication for the treatment of opioid use disorder in any care or criminal justice setting is denying appropriate medical treatment” [ ].

This statement is backed up by a multitude of evidence, accumulated over the last few decades particularly in the criminal justice system. In the general population, both methadone and buprenorphine, opioid agonist therapies used for the treatment of opioid use disorders, have been shown to reduce opioid misuse compared with abstinence-only interventions. [ , ]. When compared with abstinence-only interventions, opioid agonist therapy among justice-involved populations has not only been associated with lower rates of opioid misuse but also with higher retention in treatment, lower illicit substance use, and in some cases lower rates of recidivism [ , , ] (Hedrich, 2012). Rhode Island, at the time of writing this chapter, is the only state that provides comprehensive MAT services, including screening for opioid use disorder and treatment with buprenorphine, methadone, or depot naltrexone within all state correctional facilities. It accomplished this goal by utilizing 12 community-based Centers of Excellence for MAT to promote transitions and referrals of inmates during and postincarcerations. The state of Rhode Island has already demonstrated in preliminary data from the first year of comprehensive MAT services notable success in decreasing the state’s rate of fatal overdose of justice-involved individuals [ ].

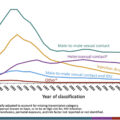

Despite the increasing evidence of the benefits of MAT in criminal justice settings, most correctional facilities currently rely on, at best, an opioid antagonist like naltrexone, and at worst, induced opioid withdrawal, masked as “drug-free detoxification” [ ]. In addition to correctional facilities historically declining provision of MAT for people with opioid use disorder (with the exception of methadone for pregnant women, a well-accepted standard of care), some drug courts, judges, parole, and probation agencies have expressed concern with regard to the need for agonist treatment, believing that buprenorphine and methadone are replacing one drug for another. This belief and stigma presents itself in referral sources for treatment. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) compiles and manages data regarding treatment admissions in state-regulated treatment facilities within the United States, labeled the Treatment Episodes Data Set-Admissions (TEDS-A). A retrospective study looking at the TEDS-A data for sources of referral for these treatment facilities found that justice-referred individuals were significantly less likely to receive agonist medications as part of their treatment plan compared with those referred through other sources. Less than 5% of people referred to substance use treatment for opioid use disorder through the justice system received opioid agonist treatment, compared with over 40% of people referred through other sources [ ].

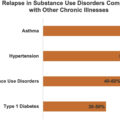

Due in large part to the criminal justice system’s historical preference for antagonist or abstinence-based therapy, many facilities that receive funding from the criminal justice system or housing must also support nonmedication-based treatments. Instead of clinically proven medical agonist treatment, medically supervised withdrawal (“detox”) is used, and return-to-use rates following detox have been reported to be as high as 65% to 91%. If patients return to using opioids post incarceration, this approach also carries a high risk of overdose due to a reduced tolerance [ ].

As of late, however, multiple lawsuits have been filed against correctional facilities across the country denying inmates access to treatments like methadone and buprenorphine for their opioid use disorders. These cases will likely move the dial on better access to medications for opioid use disorder during incarceration. Despite expected progress, we still are in dire need of providers to prescribe these medications.

While people with HIV and hepatitis C are incarcerated and being treated for these and other IDs, it could not be a more opportune time to discuss treatment for opioid use disorder with patients. This work can be done seamlessly by ID specialists, both within correctional facilities and through outpatient collaboration with correctional facilities to see patients upon release.

The benefits of concurrent treatment of opioid use disorder and infectious diseases in criminal justice settings

An estimated one-third of formerly incarcerated individuals living with HIV/AIDS have an opioid use disorder [ ]. People who inject drugs are at increased risk of contracting bloodborne illnesses, through needle- and other drug paraphernalia-sharing, along with sexual contact, all of which are more complicated to identify and treat in a correctional setting. Drug injection is a major method of HIV transmission, such that the National Institute on Drug Abuse has identified drug treatment as its principal strategy for preventing HIV and AIDS among this population.

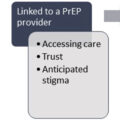

Patient preference has been noted for receiving treatment for opioid use disorder and IDs, particularly HIV and HCV, in one location. Reasons cited include stigma, difficulty accessing multiple sites of care, cost, and comfort with providers, among many others [ ]. Thankfully, any physician can easily obtain their waiver through an 8-h training in order to prescribe buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorders. Adding this to the fact that most ID specialists already have a thorough understanding of the effects of substance use disorders on their patients’ lives, an ID specialist becomes the obvious choice of provider. Patient preference is complemented by evidence that MAT and ID treatment are more effective when provided in tandem.

In a recent systematic review, 12 studies in opioid treatment settings identified improved HIV screening uptake and clinical benefits with antiretroviral therapy when provided on-site [ ]. In addition to improving screening uptake, treatment of opioid use disorder with opioid agonists has been demonstrated in systematic reviews and metaanalyses to reduce an individual’s risk of acquiring HIV by about 54%, as well as reducing an individual’s risk of acquiring HCV by about half [ , , ]. As stated in a previous section, ID specialists can contact correctional facilities to provide this care while individuals are incarcerated, and perhaps more importantly build bridges for patients to more easily access care on release.

Transitions of care surrounding release, the role of the ID physician

Within the first 2 weeks after release from incarceration, there is greater than a 100-fold higher risk of fatal overdose for justice-involved individuals, compared with the general population [ ]. The transitions of care at time of release for patients are a critical point at which outpatient ID specialists are uniquely poised to link patients to success in the community. One retrospective cohort study that followed over 2000 HIV-infected inmates in the Texas prison system demonstrated 95% of people on HIV treatment at the time of release had their treatment interrupted (i.e., did not fill a prescription for ART within 10 days), a time at which they were more likely to engage in sexual relationships and/or drug use, thus being more likely to transmit the infection [ ]. In addition to an increase in risky behaviors at the time of release, individuals are obviously more likely to develop resistance to ART with missed doses [ ].

Typically, patients do not only have HIV or HCV and criminal justice involvement but also often have mental illness, trauma, psychiatric conditions, and other medical issues, in addition to tremendous social and legal problems. HIV + patients on buprenorphine maintenance treatment who have been recently incarcerated are more likely to be homeless, unemployed, and previously diagnosed with mental illness, compared with those who were not recently incarcerated [ ]. Given these known barriers to care and social determinants of health, the biggest challenge often is to maintain a continuity of care through release and into the community. Here exists the real opportunity to help stop people from discontinuing life-saving medications or relapsing to drug use. If there is a familiar face or any type of warm hand-off, even if it is possible to meet part of the care team (healthcare provider, case worker, nurse, telemedicine visit) prior to release, this can change the trajectory of a patient’s reentry into a person’s community. Coordination of care at release is imperative to achieve better health outcomes.

While the current state of fragmented healthcare for justice-involved individuals postrelease feels like an uphill battle, we do have some effective tools to engage this vulnerable population. For one, methadone initiated in prison or immediately postrelease is associated with reduced HIV and overdose risk compared with counseling in prison without methadone and passive referral to treatment at release. Significant declines in risky behaviors are also noted in association with methadone treatment during the postrelease time periods [ ]. Initiation and maintenance on buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone, like methadone for OUD, has also been shown to improve HIV outcomes [ , ]. Unlike methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed by ID specialists for the treatment of OUD. ID specialists in the community have the ability, and, we believe, the moral responsibility, to treat individuals at the greatest risk of contracting and living with bloodborne illnesses.

All healthcare providers preventing and treating IDs should be assessing risk and identifying harm reduction measures. This includes asking their patients about justice involvement. An integrated delivery system is necessary to achieve goals of HIV suppression, HCV cure, reduction of overdoses, and opioid use disorder treatment. The criminal justice system provides an unparalleled opportunity for ID specialists to engage in this work.

We must also acknowledge that the discussion around incarceration should not just be about IDs, incarceration nor opioid use disorder, but also about combating the overarching discrimination in who becomes involved in the criminal justice system. Much of the risks for HIV, HCV, and opioid use disorder parallel high rates of trauma, poverty, homelessness, depression, and a whole host of other social determinants of health. The fact that one in three black men will end up involved in the criminal justice system tells us that race and the ZIP code you were born into may be more predictive of incarceration than anything else. Physicians can play a role in advocating for a fair criminal justice system, as well as for improved access to healthcare within and outside this system.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree