Acknowledgements

Dr. Akhtar is supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse award number 2UG3DA044826. Dr. Feinberg is supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse award number 2UG3DA044825 and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences award number 5U54GM104942-04.

Opioid use disorder burden in rural communities

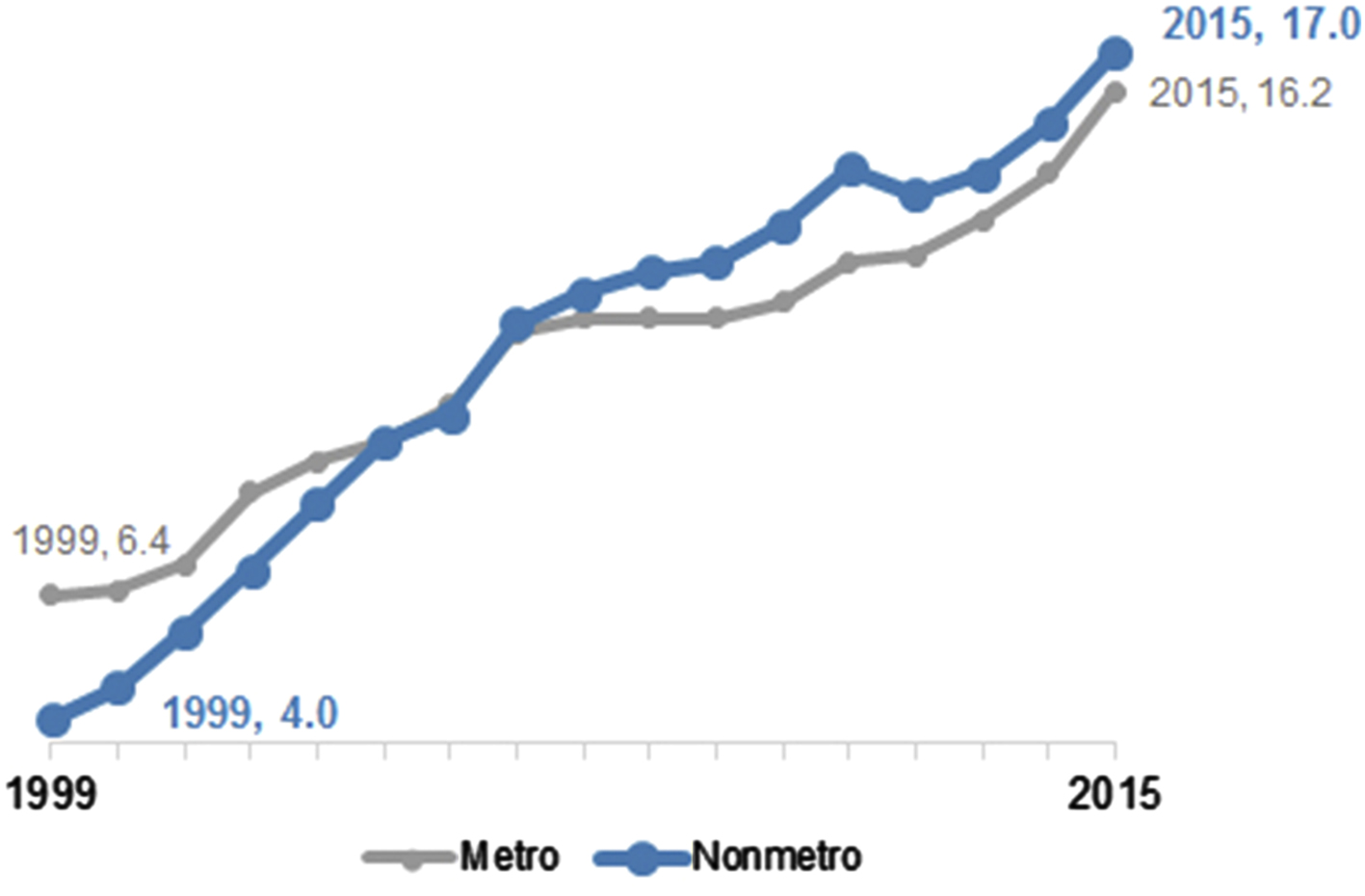

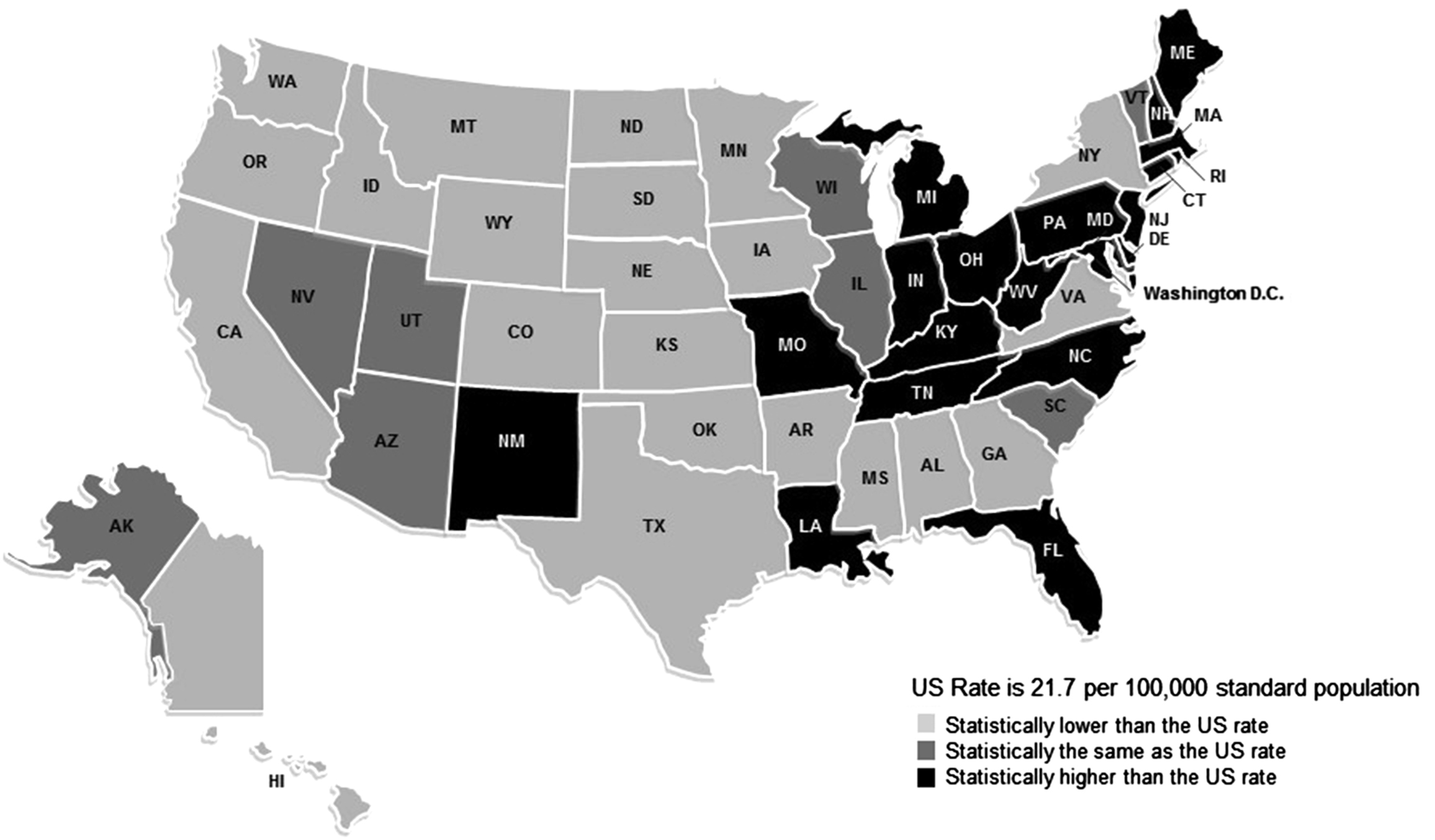

Although the overall prevalence of drug use in rural areas is lower than that in urban areas, the looming opioid epidemic has caused the rate of overdose deaths in rural areas to increase and surpass the rate seen in urban areas [ ]. As shown in Fig. 3.1 , the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a 325% increase in drug overdose deaths from 1999 to 2015 in nonmetropolitan counties of residence compared with 198% among metropolitan counties of residence [ ]. In 2017, age-adjusted drug overdose rates were highest among states with large rural populations, such as West Virginia, Kentucky, Maine, and Ohio ( Fig. 3.2 ) [ ]. Additionally, several studies have reported that nonmedical prescription drug use has been mostly concentrated in nonmetropolitan areas, which is a change from the previous experience of urbanized areas [ ].

In a meta-analysis by Brady et al. [ ], the investigators reviewed qualitative and quantitative studies in order to identify risk factors associated with prescription drug overdose death. Twenty-nine studies were assessed for six risk factors: sex, age, race, psychiatric disorders, substance use disorder, and urban/rural residence. All were associated with drug overdose deaths except for urban/rural residence. These findings are of particular interest because rural overdose death rates are exceeding those in urban areas, yet the most current meta-analysis did not find a statistical association. This could be due to the wide array of ways rurality can be assessed in studies. Studies often describe urban and rural by population density, or by grouping micropolitan and metropolitan as urban. Varying definitions of rurality may result in attenuation of the overall effect it has on overdose deaths [ , ].

Human immunodeficiency virus

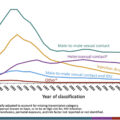

Between 2008 and 2014, the overall number of new HIV diagnoses among persons who inject drugs (PWID) fell in the United States. This was driven largely by the approximate 50% decline among urban PWID of color [ ]. However, transmission by injection drug use (IDU) in nonurban areas contributed to new HIV cases in greater proportion than in urban areas [ ]. The HIV outbreak in Scott County, Indiana, was the first in the United States that resulted from the rural opioid epidemic. Additional outbreaks have emerged since then. Between January and July 2017, 57 HIV cases emerged across 15 counties in the southern coalfield counties of West Virginia [ ]. Although 60% of the cases reported male-to-male sexual (MSM) contact as the mode of transmission and 10% endorsed both MSM contact and IDU, 23% either could not be found or refused to speak to the CDC investigators, raising the possibility that some or all had IDU risk. From January 2018 through February 2019, 30 PWID were diagnosed with HIV in Cabell County, West Virginia, a county that had previously averaged eight new HIV cases annually based on data from 2013 to 2017 [ ].

Between 2015 and 2018, 129 new HIV cases emerged in the cities of Lowell and Lawrence, Massachusetts [ ]. Although Lowell and Lawrence are not rural communities, early arrival of fentanyl, homelessness, incarceration, and a decline in HIV testing were factors that played a crucial role in the spread of HIV there—the same factors that are increasingly evident in rural communities [ ].

Hepatitis C, B, and A virus infections

The CDC reported a 2.9-fold increase in reported cases of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections from 2010 through 2015, reflecting the increased rates of IDU, occurring mostly among young white persons living in rural communities [ , ]. Interestingly, the states with the highest rates of new HCV infections during this period—Kentucky, West Virginia, and Tennessee—were not receiving CDC funding for case finding. This reflected not only underascertainment and underreporting in these communities but also the deeper issue of limited healthcare and public health resources in rural communities with a high burden of opioid use disorder (OUD) and IDU.

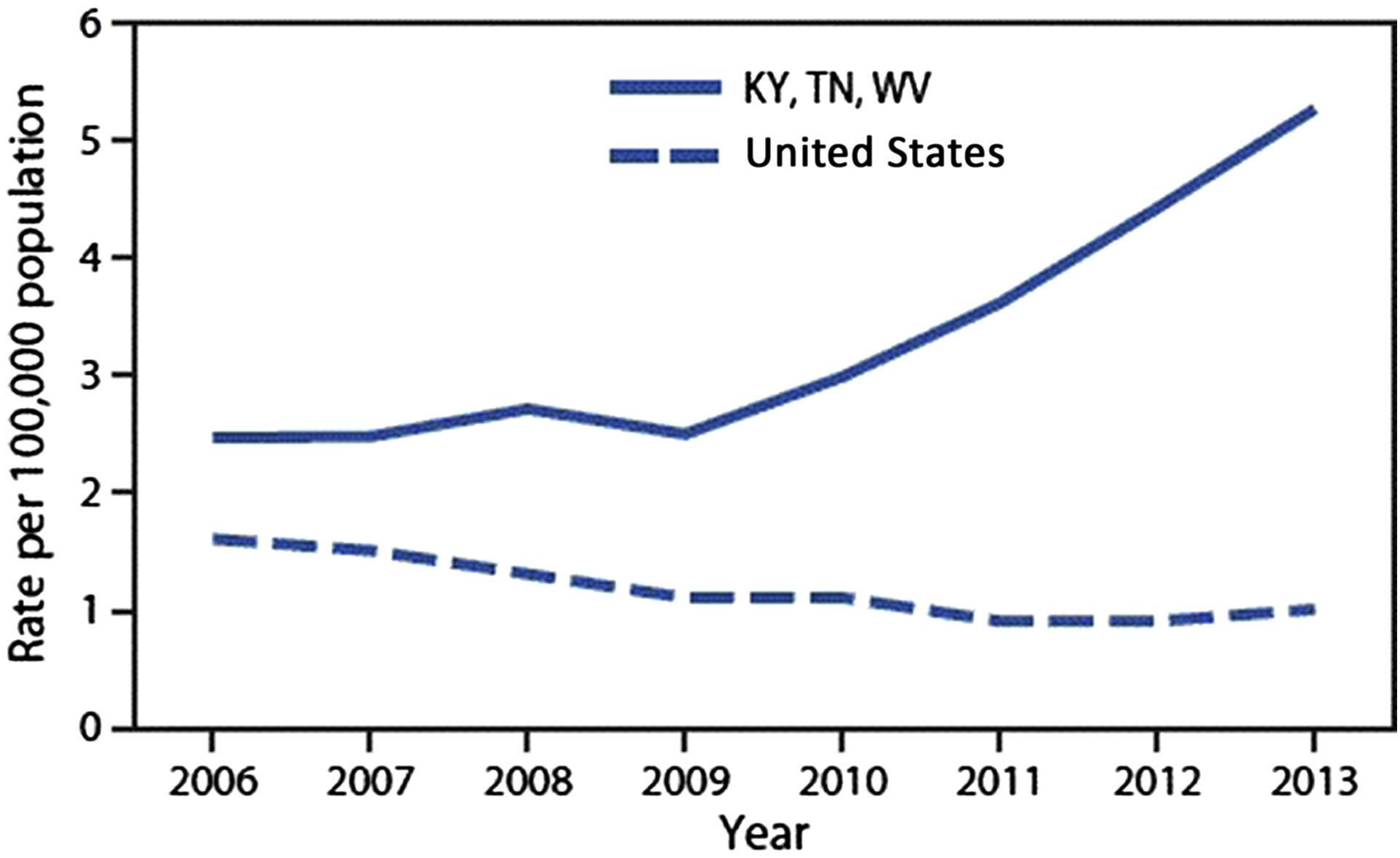

Using data from the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, the CDC assessed acute hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections in the same three states where HCV infections were high. Acute HBV infections also increased in Kentucky, West Virginia, and Tennessee ( Fig. 3.3 ) among non-Hispanic whites aged 30–39 years in nonurban communities [ ]. While the rate remained stable for the United States overall, the rate of HBV infections increased by 114% in 5 years in these three states [ ].

In the past few years, hepatitis A virus (HAV) outbreaks have occurred among people who use drugs (PWUD), the homeless community, and men who have sex with men [ ]. In 2017, the CDC received over 1000 reports of acute HAV infection from California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah. The majority of these cases were among IDU and non-IDU persons who use drugs and/or homeless individuals [ ]. In March 2018, a cluster of HAV infections was reported by the Kanawha-Charleston Health Department in West Virginia. Testing confirmed that the outbreak, primarily among persons who use drugs and homeless persons, was caused by genotype 1B, the strain identified in ongoing HAV outbreaks in multiple states [ ]. A retrospective review identified a total of 664 outbreak-associated cases from January 1, 2018 to August 28, 2018 that were epidemiologically linked to “… an identified outbreak case, a laboratory specimen matching the outbreak strain, or occurred in a person at high risk for infection (e.g., reported injection or noninjection drug use, experienced homelessness or unstable housing, or was recently incarcerated) ….” Morbidity included hospitalization among 57% ( n = 380) of the cases. Although mortality from HAV infection is unusual, one death has been reported in this outbreak, and deaths have been reported in San Diego and other localities with recent HAV outbreaks. This may have been exacerbated by concurrent past or current HCV infection in 314 cases (47%), past or current HBV infection in 65 cases (10%), and homelessness in 100 cases (15%). As routine surveillance data on incident cases continues to become available, the CDC expects increases in HAV infection among PWUD and/or homeless people—two characteristics that are evident in rural communities [ ].

Factors that drive illicit drug use in rural communities

To explain the discrepancies evident in urban and rural illicit drug use, Keyes et al. [ ] developed hypotheses regarding the disparity and shift in burden. First, there is an increase in the availability of opioids among states with large rural populations shown by high dispensing rates of prescription opioids. Rural communities, especially in central Appalachia, were exposed to aggressive marketing by prescription opioid producers such as Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin [ ]. The aggressive marketing can be due in part to the higher rates of older persons who may be susceptible to chronic pain and to the drug use culture in Appalachian communities where prescription opioids are often used by mine and other heavy occupation workers [ ]. Keyes et al. theorized that the high density of opioids available in rural communities can create opportunities for illegal markets to arise.

Second, rural communities have experienced an out-migration of young adults resulting in an aged workforce and an unstable economic infrastructure [ ]. The vulnerability caused by economically deprived communities may increase the risk of substance use disorders [ ]. In one qualitative study, four groups of key informants in Appalachian Kentucky described opioid misuse as an escape from hopelessness and lack of opportunity [ ].

Third, large rural social and kinship network connections may contribute to the spread of opioid misuse. Unstable economic infrastructures described earlier, coupled with wider kinship networks in rural communities, can generate strain on that broader social network, thus increasing the risk of opioid misuse across a community [ ]. Additionally, prescription opioids that were legitimately filled by parents, relatives, and friends were the main initial source of drug use in rural communities. This was evident in the Scott County HIV outbreak, where the size of the PWID network and the amount of syringe sharing were large for a sparsely populated area [ ].

Finally, rural communities have faced industry and labor shifts. These shifts led to high rates of unemployment and fewer opportunities for upward mobility [ ]. Such stressors can also increase the risk of substance use and misuse. Keyes theories gave the public health community context for the complexity of the rural opioid epidemic in order to begin understanding what is needed for treatment and care.

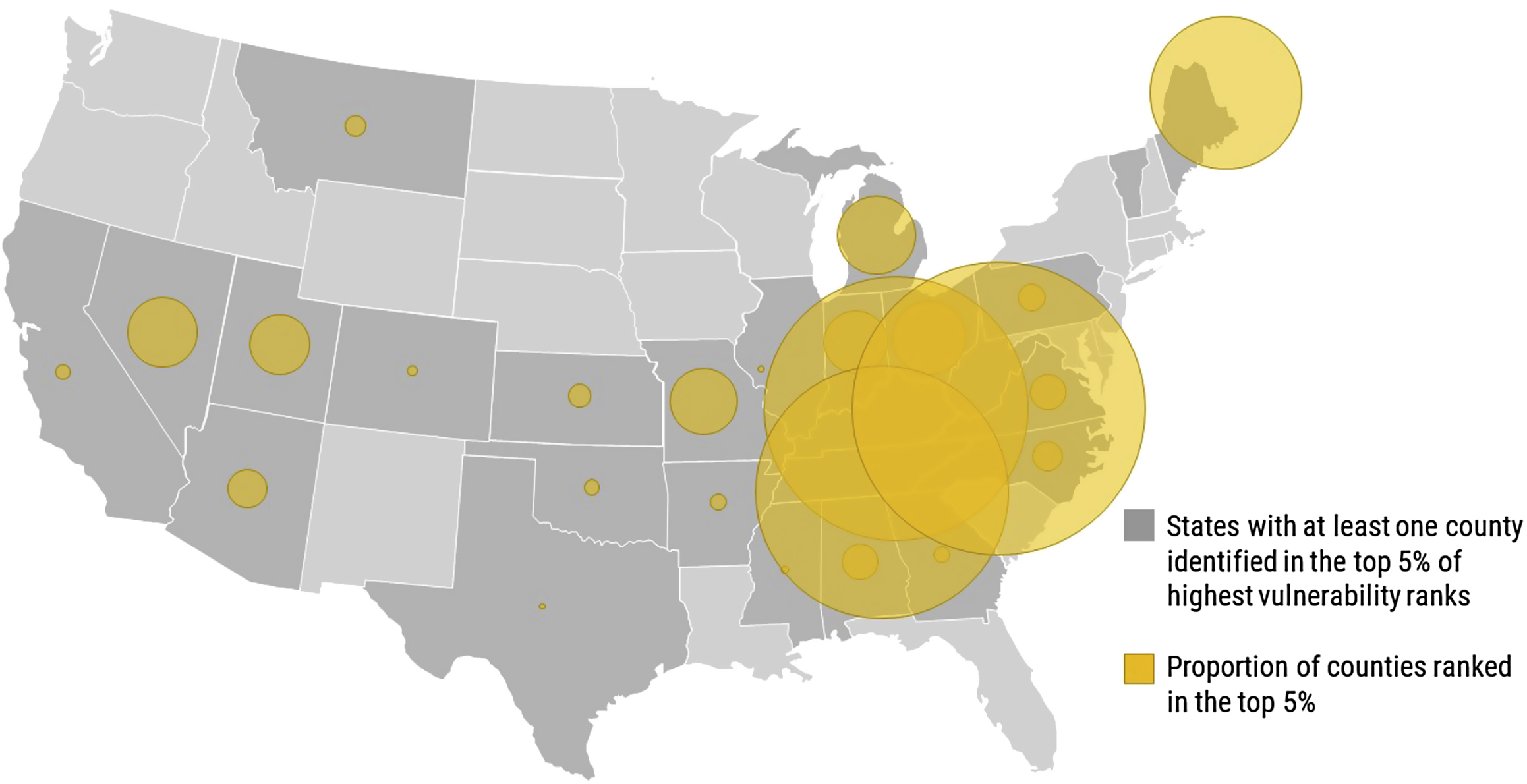

In response to the Scott County HIV outbreak, the CDC and the public health community raised concerns about the vulnerability of similar HIV outbreaks occurring in rural areas affected by the opioid epidemic. The socioeconomic characteristics of Scott County are not unique; other rural areas also face high unemployment, poverty, and low educational attainment. Identifying these communities became vital in order to guide public health efforts. Van Handel et al. [ ] utilized a multistep analysis to identify factors that are highly associated with IDU and then identified 220 rural counties in 26 states that are most vulnerable to an HIV outbreak similar to that in Scott County by using confirmed cases of acute HCV infection from 2012 to 2013 as a proxy for IDU and 15 county-level indicators that were available nationally ( Fig. 3.4 ). The authors found six indicators associated with acute HCV infection: drug overdose deaths, prescription opioid sales, per capita income, white non-Hispanic race/ethnicity, unemployment, and the number of buprenorphine providers per 10,000 population. The greatest proportion of counties identified were largely rural with the majority in central Appalachia—Kentucky, West Virginia, and Tennessee. Scott County ranked 32nd in their analysis.

Barriers to care in rural communities

Coupled with the findings from the studies by Brady, Keyes, and Van Handel, it is imperative to understand barriers that patients, providers, and communities face in accessing and providing essential prevention and treatment services in rural areas. The first major factor rural communities face is the lack of specialty medical services, especially mental health and addiction treatment and infectious disease specialists to manage the serious sequelae of IDU. It is estimated that 80% of rural counties have no psychiatrists, 61% are without psychologists, and 91% are without psychiatric nurse practitioners (NPs) [ ]. In a survey conducted by Andrilla et al. [ ], 60% of rural counties lack a physician with a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) waiver to prescribe buprenorphine and among rural providers who had a waiver, 40% were not currently prescribing, prescribed formerly, or were not accepting new patients. It is unclear how many infectious disease specialists practice in rural communities. However, as infectious disease mortality decreases in the United States, the mortality rate in many rural communities continues to increase [ ]. This suggests that lack of access to early diagnosis of life-threatening infectious diseases, case management, and care in rural communities contribute to rise in mortality.

A multitude of logistic barriers exist in rural communities. For providers who are willing to offer medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for OUD, the number of potential patients may not justify the start-up costs, office space, time, and resources needed to start an MAT program [ ]. State regulations, such as those in West Virginia, require a range of resources that may not be available in rural communities, such as availability of psychosocial counseling. Additionally, if services are available, rural communities lack public transportation options that will allow patients, who already are economically burdened, to travel to appointments. In mountainous central Appalachia, short distances can require long travel times because of the terrain and road conditions. Longer travel time for treatment may increase the risk of jeopardizing a patient’s employment status and adherence to treatment [ ]. Lastly, in states that have not implemented the Affordable Care Act, poverty and low employment rates preclude the option of buying private health insurance that covers care for OUD.

Developing and training the rural healthcare workforce

In lieu of specialists, rural communities depend on primary care providers (PCPs) to treat patients with OUD and the infectious consequences associated with IDU. Primary care may be practiced in a variety of settings and facilities in rural communities, including family physicians and internists in private practice, rural community health clinics, and federally qualified health centers that play an important role in serving rural residents. Rural residents of federally recognized tribes rely on the Indian Health Service that provides care to Native Americans and Alaskan Natives.

Among all buprenorphine prescribers, rural providers most frequently reported concerns about diversion or medication misuse, time constraints, and lack of available mental health or psychosocial support services as barriers to provide buprenorphine treatment [ ]. In another survey by Andrilla et al. [ ], nonprescribers were more likely to report time constraints, lack of patient need, resistance from practice partners, lack of specialty backup for complex problems, lack of confidence in their ability to manage OUDs, concerns about DEA intrusion on their practice, and attraction of PWUD to their practice more often than current prescribers. In a survey conducted among Wisconsin family medicine nonwaivered physicians, providers reported that they were more likely to incorporate office-based opioid treatment if patients had access to addiction counseling, had colleagues on-site who were knowledgeable about buprenorphine, and had access to a teleconsultation program [ ]. Moreover, widespread stigma against MAT that is seen as substituting “a drug for a drug” is yet another obstacle to the effective treatment of OUD even when it is available in rural settings. The sentiment against MAT is persistent among even the highest federal health officials. In 2017, Tom Price, the former Health and Human Services Secretary for the United States, was quoted saying, “If we’re just substituting one opioid for another, we’re not moving the dial much,” when he was on a listening tour in West Virginia [ ].

PCPs in rural communities are also tasked with the responsibility of either independently managing their patients living with HIV infection and/or chronic viral hepatitis (HCV and HBV infections) or referring them to a specialty provider, where patients may have to travel long distances and wait many months for an appointment. An overwhelmingly majority of PCPs still refer patients with HIV and HCV infections to specialists, even though advances in antiretroviral therapy and the development of curative, direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for hepatitis C has made treatment simpler, safer, and highly efficacious in a primary care setting. Regardless of background and training, clinical outcomes among people living with HIV (PLWH) infection are associated with the provider’s experience in managing HIV infection [ ]. Because of the population size in rural communities, PCPs may not able to garner enough PLWH infection to develop the needed experience [ ]. Nonetheless, data still suggests that both PCPs and NPs have comparable HIV and HCV treatment outcomes, such that infectious disease providers should collaborate with rurally practicing PCPs and NPs to expand treatment in hard-to-reach areas and to bridge gaps in the continuum of care for patients living with HCV and/or HIV infection [ ].

Attitudes toward the use of DAAs among PWID in some communities may present continued barriers to treatment, mainly because of concerns of HCV reinfection and perceived nonadherence. The stigma around IDU in rural areas may exacerbate these concerns. However, a number of studies in PWID have shown that they can achieve the same sustained viral response at 12 weeks after the completion of therapy (SVR12, or cure) as other populations [ ]. In the SIMPLIFY study, an open-label phase 4 study using the pan-genotypic combination of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir (Epclusa) for 12 weeks among 103 individuals who had injected drugs during the prior 6 months, the SVR rate was 94% (95% confidence interval, 88–98) and there were no virologic failures [ ]. Available data show comparable cure rates in PWID as in the non-drug-using population and low but tolerable reinfection rates [ ].

Community stigma, support, and policy

Although Keyes’ theories revealed that large kinship circles in rural communities may allow for the spread of drug use and that the overall culture of miners and heavy machinery workers chronically taking opioids had normalized prescription opioid use, the stigma surrounding OUD poses a significant barrier that may discourage people from seeking prevention and treatment services. Studies have shown that patients with OUD are less likely to seek treatment out of fear that it would affect their employment and social relationships with friends, family, and neighbors [ ]. The conservative climate, religiosity, and concerns about confidentiality are added barriers to effective HIV and HCV infection prevention and care in rural communities [ ]. In order to achieve community buy-in, education on the effectiveness of MAT and routine HIV/HCV testing and treatment is warranted.

A few strategies to build support for MAT in rural communities were presented as case studies by the program funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, “Advancing Recovery: State/Provider Partnerships for Quality Addiction Care.” For example, in order to overcome community resistance, Advancing Recovery West Virginia shared success stories with local papers and other media outlets [ ]. Advancing Recovery Maine worked to build statewide support for MAT by creating a recovery community called Maine Alliance for Addiction Recovery. The alliance worked to identify beliefs and attitudes toward the use of MAT, along with challenges that providers and patients may face in implementing MAT [ ]. The results were then used to provide training events statewide. Patients with OUD and/or IDU frequently interact with a network of community members, including law enforcement, drug courts, probation officers, child protective services, local healthcare providers, and other community members. Efforts from local agencies with an informed approach on the disease of addiction, rather than the widespread belief that it is a character flaw or lack of willpower, and the commitment to the possibility of recovery and social reintegration, need to be integrated into the overarching community.

Local, state, and federal policies play a role in the successful prevention and treatment of HIV/HCV infection and OUD in rural communities. However, implementation of these policies may vary by jurisdiction. For example, many states have enacted a “Good Samaritan Law” by which PWUD are offered immunity from prosecution for certain drug-related offenses if they call emergency personnel when another person overdoses. As the number of overdose deaths increases, some prosecutors are treating overdose deaths as homicides and charging those who may have tried to save the victim [ ]. With ambiguous laws and/or ambiguous interpretations in place, PWUD may not report overdoses, thus increasing the risk of overdose death.

Another example of a policy barrier is the discriminatory practices of some state Medicaid agencies. There are a range of restrictions to access curative therapy for HCV infection and OUD. States may require that patients reach a certain stage of liver fibrosis, which increases the risk of irreversible liver disease (cirrhosis) and hepatocellular carcinoma, or may refuse treatment to a patient with a history of alcohol or substance use or require evidence of sobriety for a specific duration. Additionally, Medicaid may restrict prescribers to specialists in gastroenterology/hepatology and infectious diseases that may not be accessible to rural PWID. Although there has been a heartening trend to reverse these restrictions nationwide, often as the result of lawsuits, restrictions remain in many hard-hit states. Additionally, among states that have begun reversing Medicaid restrictions for the treatment of HCV infection, few providers are aware of the changes even a year after the policy change and stigma in treating may still remain [ ]. Interestingly, as Medicaid programs continue to enroll recipients into managed care organizations (MCOs), a few states allow for their MCOs to implement more restrictive criteria than their state’s fee-for-service Medicaid restrictions [ ]. Jurisdictions then have inconsistent criteria to offer HCV treatment to PWID.

All states offer some form of medication for MAT that is covered by their state Medicaid program. However, some states may limit the quantity or dosing, require prior authorization, require additional psychosocial treatment, and require step therapy [ ]. Although requiring prior authorization for psychiatric medication has shown to reduce medication expenditures, the requirements may prevent timely access to treatment by an unstable PWID community. Additionally, step therapy is a common requirement through Medicaid, where a certain drug may not be used unless one or more other drugs are tried and were unsuccessful in treatment. However, this can become a barrier to treatment among PWID.

Promising models for prevention and treatment in rural communities

Evidence-based models of care that offer MAT services have been discussed elsewhere [ ]. These include (1) the Project ECHO model of linking academic medical centers to resource-limited areas for various medical conditions, (2) the office-based opioid treatment collaborative care model where nurse case managers take on the responsibility of complex care, and (3) the Hub and Spoke Model where emphasis is in care coordination with a “hub” program that initiates treatment and “spoke” clinic for ongoing management, such as the Vermont model [ ]. There are also ongoing studies to understand rural IDU, opioid use, and their infectious disease consequences, along with the effectiveness of evidence-based interventions on these communities.

Current studies on rural injection drug use

Rural opioid initiative

In order to improve understanding of the intersectionality of opioid use and HIV, HCV, and comorbid conditions, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) funded a rural opioid initiative in 2017, with collaboration from other federal co-funders: the CDC, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). This initiative was designed by NIDA and its partners to conduct community assessments; to use the assessments to design plans for implementing evidence-based practices to address opioid use, IDU, overdose, HIV infection, and other infectious comorbidities; and then to evaluate implementation of these plans. The overall objective of this initiative is to identify best practices that can be disseminated to address the unique needs of rural communities Project sites are located in Ohio, North Carolina, Kentucky, West Virginia, Oregon, Illinois, Wisconsin, and a northeast rural region encompassing Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. To date, this cooperative agreement is the largest study assessing rural opioid and IDU in the United States. Data from the core instruments will provide a unique snapshot across the eight sites and a larger picture of the rural opioid epidemic, HIV infection, and related infectious comorbidities.

The project encompasses two phases: multimethod community assessments during the first 2 years and implementation of evidence-based practices based on those assessments in the last 3 years. The intervention projects will provide not only additional information about the epidemiology of HIV and related infectious comorbidities among opioid users but also important information about how evidence-based practices can be implemented effectively, given the challenges and obstacles in rural communities.

Healing communities study: developing and testing an integrated approach to address the opioid crisis (Healing communities)

Understanding that only a small percentage of people with OUD actually receive MAT, behavioral interventions, and naloxone to reduce overdoses, NIDA has solicited grant applications to increase access to these resources with the primary goal of reducing the opioid overdose fatality rate by 40% in a 3-year period. Three research sites will be funded to test the immediate impact of implementing an integrated set of evidence-based intervention across healthcare, behavioral health, justice, and other community-based settings to prevent and treat opioid misuse and OUD among highly affected communities. Healing Communities has an emphasis on rural communities and, in addition to the primary aim of decreasing overdose fatalities, includes a number of secondary outcomes such as reducing the supply of prescription opioids, increasing the number of specialty treatment programs and buprenorphine-waivered providers, increasing the availability of naloxone to reverse overdoses, screening to identify opioid misuse, evidence-based school and community-based prevention services, and a number of formal linkages between the justice system and healthcare.

It is anticipated that these research programs will improve our understanding of the nature of the rural opioid use and IDU epidemic and will demonstrate effective approaches to limit the associated morbidity and mortality in rural communities. It cannot happen too soon.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree