Injection drug use is an important HIV risk factor

Transmission among People Who Inject Drugs (PWID) early in the HIV epidemic

Soon after the identification of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), it became clear that injection drug use was a major risk factor for the acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Des Jarlais and colleagues tested for HIV antibodies in stored sera from people who inject drugs (PWID) who entered opioid treatment programs in New York City and found that HIV seroprevalence increased from below 10% in 1978 to 50% in 1983, with stabilization thereafter [ ]. This observation highlights the rapidity with which HIV was able to spread in an unprepared and underresourced population of PWID. However, the finding that HIV seroprevalence plateaued at 50%–60% contrasted with hepatitis B virus seroprevalence of greater than 80% in studies of PWID, suggesting that HIV was less infectious in this context than hepatitis B virus. Other studies identified HIV nucleic acids in 39%–68% of used syringes recovered by syringe service programs (SSPs) or retrieved from shooting galleries [ , ].

Analyses, using varying methods, estimate that the transmission risk for a single episode of needle sharing from an HIV-positive to an HIV-negative individual is approximately 7 per 1000 exposures, with a range from 6 to 16 per 1000 [ , ]. Compared with other transmission risks [ ], needle sharing is more risky (per episode) than penile-vaginal intercourse or accidental needlesticks, but slightly less risky than unprotected receptive anal intercourse, and much less risky than the transmission risk from mother to child or from a blood transfusion from an HIV-positive source patient ( Table 5.1 ).

| Exposure type (references) | HIV transmission risk per 1000 exposures (estimate range) |

|---|---|

| Penile-vaginal intercourse [ , ] | 1 (0.8, 1.0) |

| Insertive anal intercourse [ ] | 2 (0.6, 6.2) |

| Accidental percutaneous needlestick [ ] | 2 (0, 24) |

| Needle sharing during injection drug use [ , ] | 7 (6, 16) |

| Receptive anal intercourse [ ] | 14 |

| Maternal to child transmission [ ] | 226 |

| Blood transfusion [ ] | 925 (270, 1000) |

Viral load in the source individual is a strong and consistent determinant of HIV transmission across all exposure categories [ ]. Among PWID, behaviors that increase the risk of HIV acquisition include frequency of sharing, younger age, injecting in shooting galleries [ ], concurrent sexual risk factors [ ], and use of syringes with relatively high dead space [ ].

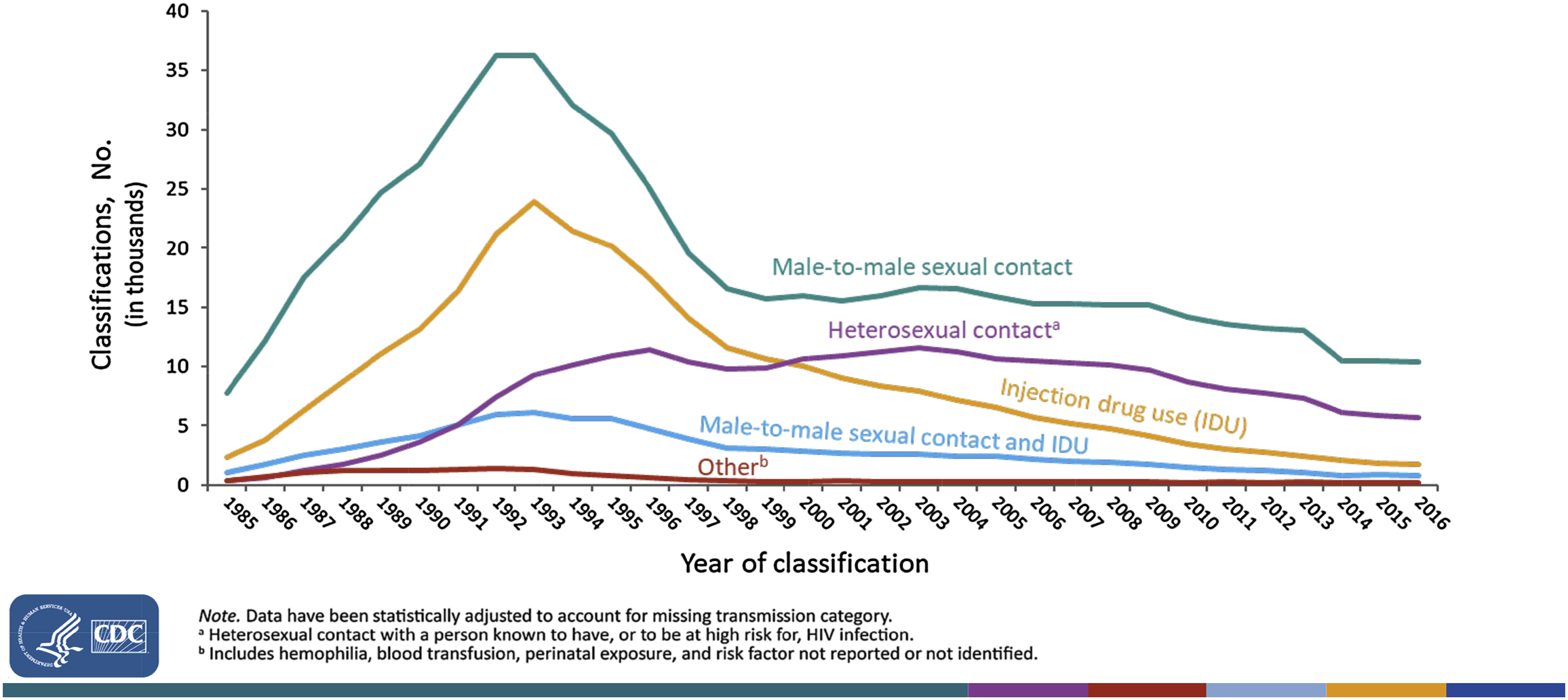

The (largely unheralded) success of HIV risk reduction among PWID

According to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), PWID accounted for over 30,000 new HIV infections annually in the late 1980s, and, briefly, had a higher rate of new infections than men who have sex with men (MSM) [ ]. By the early 1990s, HIV incidence rates had fallen sharply for both MSM and PWID, but while MSM-related incidence rebounded and tracked upward through 2006, PWID-related infections continued on a downward course. In 2015, the most recent year for which the CDC has estimates [ ], only 2200 HIV infections were attributed to injection drug use, 5.7% of HIV infections that year (another 1200 infections were attributed to men with same sex exposure and injection drug use). In a long-running community-based cohort study of PWID in Baltimore, the HIV incidence declined from 4.6% annually in 1988 to near 0% by 2001 [ ], and a similar decline in estimated HIV incidence among PWID in New York City was reported in serial cross-sectional surveys [ ]. Compared with the late 1980s peak, HIV infections attributed to injection drug use have declined over 90% nationally, an accomplishment second only to the decline in infections attributed to mother-to-child transmission [ ]. Fig. 5.1 shows the numbers of adults and adolescents diagnosed with AIDS by calendar year since 1985. Although AIDS diagnoses are not necessarily an accurate reflection of new infections, this figure underscores the long-term success of reducing HIV disease attributable to injection drug use.

Factors contributing to declining HIV incidence among PWID: 1992–2015

There are several factors that likely contributed to the large decline in HIV incidence among PWID in the United States and most other higher-income countries. The most important factor was reduction in needle sharing among PWID, aided, where available, by SSPs.

Reduced needle sharing and syringe service programs

Between 1991 and 1994, the estimated number of clean syringes provided in New York City increased fivefold to 1.3 million per year [ ]. Among PWID recruited in New York City, receptive needle sharing in the prior 6 months declined from 42% in 1990–91 to 24% in 1996–97. In tandem with reduced injection-related risk, reported use of SSPs and HIV testing approximately doubled over this same time period [ ]. Additionally, PWID who were aware of their HIV-positive status when surveyed reported 65% lower odds of unsafe sex with and 37% lower odds of distributive syringe sharing (behaviors that put others at risk), but no difference in receptive needle sharing, compared with other PWID, highlighting the importance of HIV diagnosis in supporting behavioral changes that reduce the risk of onward transmission [ ]. In addition to providing access to clean needles/syringes, SSPs provide additional services to this hidden and difficult to reach population, including HIV testing, wound care, and referrals to drug treatment programs.

Although never evaluated in a randomized controlled trial, a wealth of observational data supports the benefits of SSPs in reducing HIV transmission and dispels concerns that providing clean syringes encourages drug use [ ]. The CDC [ ], the Institute of Medicine [ ], and the World Health Organization and other international health organizations [ ] strongly endorse SSPs as an essential service for PWID to reduce HIV transmission.

The full potential benefits of SSPs in the United States have not been realized due to inadequate support and implementation. Political support for SSPs has been tepid and grudging at best, and outright hostile at worst. The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Australia began implementing robust SSPs in the 1980s when the rapidity of HIV transmission among PWID became clear. At that time in the United States, almost all states had laws criminalizing possession and distribution of drug paraphernalia, which could be invoked against SSPs. In 1988, the federal government instituted a ban on federal funding for SPPs, which has remained in effect since, with the exception of a one-year period in 2009 [ ]. Consequently, legislative support and funding for SSPs has been left up to state and local governments, with substantial heterogeneity across states. In a 2014 review of state laws in 36 states with available data, there were 10 states that had not passed laws explicitly authorizing SSPs and provided no public funding for SSPs [ ]. In this analysis, the authors found a correlation between an absence of state-level funding for SSPs and unfavorable trends in HIV incidence among PWID in the state. A global systematic review of PWID services conducted in 2010 [ ] estimated that only 22 needle/syringes were distributed per PWID per year in the United States, a distribution rate that lagged not only Canada (46 per PWID per year) and Western Europe (59 per PWID per year) but also central Asia (92 per PWID per year), south Asia (37 per PWID per year), and east and southeast Asia (30 per PWID per year). For reference, the WHO has recommended a target distribution rate of at least 200 clean syringes per PWID per year. Revealingly, a 4-year follow-up to this report assessed the six countries with the largest numbers of PWID (China, Malaysia, Russia, Ukraine, Vietnam, and the United States) and found that only two countries had made no progress in expanding coverage of SSP, medication-assisted treatment (MAT), or antiretroviral therapy (ART) to PWID since the original report—Russia and the United States [ ]. By virtue of preventing HIV infection and being relatively inexpensive per person served, expansion of SSP in the United States is highly cost-effective [ ].

Transitions from injection to noninjection use of heroin

A second factor that contributed to decreased HIV transition among heroin users has been the transition from injection as the primary route of use to intranasal use (sniffing) [ , ]. For example, among treatment seeking individuals with heroin use disorder in New York City, the percentage reporting their primary administration route as intranasal increased from 25% in 1988 to 59% in 1998 [ ]. Interestingly, this transition away from heroin injection (and the inherent risk of HIV transmission) was facilitated by increases in the purity of street heroin. The average purity of heroin on the street in New York City increased from less than 10% before 1988 to over 60% by the late 1990s [ ]. The co-occurrence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic among PWID and increased heroin purity at the level of street sales (facilitating noninjection routes of use) seems unlikely to be coincidental. One study reported that transitioning from injection to noninjection use of heroin was associated with a lower hepatitis C seroprevalence [ ].

Medication-assisted treatment

A third factor in the decades-long decline in injection drug use-related HIV transmission is the availability of effective MAT for opioid use disorder, notably methadone and later buprenorphine. Compared with being out-of-care, MAT is associated with cessation of compulsive opioid use, a two- to threefold decrease in all-cause mortality [ , ], decreased criminal activity, and improved psychosocial functioning (mood disorders, employment, relationships, etc.) [ ]. There is strong face validity and empiric support for the proposition that MAT reduces HIV incidence [ ]. An observational study in Philadelphia followed HIV-negative PWID in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the peak of the HIV epidemic among PWID in the United States, and found a 22% HIV incidence rate over 18 months in out-of-treatment PWID compared with a 3.5% incidence rate among those receiving methadone maintenance [ ]. One randomized trial, conducted in China and Thailand, aimed to compare the incidence of HIV infection or death among HIV-negative PWID with opioid use disorder randomized to risk reduction counseling combined with either short-term (18 days) or long-term (52 weeks) buprenorphine-based MAT. Although the prevalence of opioid-negative urine drug tests was approximately twice as high in long-term than short-term MAT at 26-week follow-up, the trial was stopped early for futility, because of lower than expected HIV incidence in the study cohort overall [ ]. In the United States, methadone maintenance can be provided only by heavily regulated opioid treatment programs that require patient visits multiple days a week, factors that limit rapid expansion of treatment slots.

In October of 2000, the Drug Addiction Treatment Act was passed that allowed qualified physicians, in office practice settings, to prescribe schedule III, IV, and V medications for detoxification or maintenance of patients with opioid use disorder [ ]. In 2002, buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of opioid dependence. Over the subsequent years, buprenorphine-based treatment has been increasingly prescribed and provides an important, more flexible alternative to methadone maintenance. The number of physicians qualified to prescribe buprenorphine increased from approximately 5000 in 2004 to 15,662 by 2008 [ ]. Yet, despite introduction of buprenorphine, overall MAT availability still remains inadequate in the United States, and substantially lower than in Western Europe [ , ]. Because MAT is associated with improvements in multiple domains, in addition to HIV prevention, it is highly cost-effective [ ].

Antiretroviral therapy and “treatment as prevention”

Fourth, “treatment as prevention” may have played some role in declining HIV incidence among PWID. For sexual HIV transmission, strong and consistent data support the premise that effective treatment of HIV-positive individuals greatly reduces the risk of HIV transmission to sex partners [ ]. In HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052, 1763 serodiscordant couples, in which the seropositive partner was ART naïve and had a CD4 count above 350 cells/μL, were randomly assigned to either immediate ART or delayed ART until the CD4 count had declined below 250 cells/μL (which reflected standard care at the time in the countries where conducted). Of 28 genetically linked transmission observed during the trial, 27 occurred in the delayed ART arm and 1 in the immediate ART arm, translating to 96% efficacy [ ]. Mathematical models indicate that a strategy of universal annual HIV testing and immediate treatment of infected persons is capable of ending the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa [ , ]. In contrast to the data for sexual transmission, there are no direct observational or experimental data from PWID showing that viral control with ART in an index HIV-positive person is associated with decreased HIV transmission risk to uninfected injecting partners. The HPTN 074 study explored the feasibility of measuring HIV seroconversion of uninfected injecting partners of HIV-positive index individuals as a primary outcome for a larger prevention trial [ ]. However, the overall observed incidence was only approximately 1% among uninfected injecting partners, which the authors concluded was insufficient to support a larger trial. Although direct randomized data are lacking, ecological studies among PWID suggest a link between community viral load and the risk of new HIV infections [ , ].

It is worth noting that the impact of treatment as prevention on observed declines in PWID-associated HIV incidence has likely been modest, at least to date. First, because of very high viral loads during acute HIV infection, HIV-infected persons are most infectious in the months immediately following infection. For example, among MSM, it has been estimated that half of onward transmissions from an index individual occur in the first year of HIV infection [ ] and a similar association likely applies to injection-related transmissions. Only a minority of HIV-infected individuals are diagnosed during this period of highest infectivity, which limits the impact of ART in averting transmissions. Additionally, it was not until 2015 when all major HIV treatment guidelines endorsed treating asymptomatic individuals with CD4 counts ≥350 cells/μL. Second, as discussed below, since the introduction of effective combination treatment for HIV in the 1990s, HIV-positive PWID have consistently lagged other groups in access to ART and achieving and maintaining viral suppression, which translates to reduced benefit of treatment as prevention.

Preexposure prophylaxis

A fifth consideration for declining HIV incidence among PWID is preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with oral antiretroviral drugs, which was shown to reduce HIV incidence by approximately 50% among HIV-negative PWID in Bangkok, Thailand [ ]. However, unlike MSM, where PrEP has made gains in the past 5 years [ , ], meaningful implementation or scale-up of PrEP among PWID has been extremely limited in the United States and elsewhere. For example, in a recent survey of 265 SSP clients and peers in Baltimore, Maryland, only one-quarter of participants was aware of PrEP and only two participants reported taking PrEP [ ]. Additionally, modeling studies suggest that implementation of PrEP among PWID in the United States is likely not cost-effective [ , ], due to relatively low HIV incidence among PWID currently and major competing adversities (psychosocial effects of addiction, hepatitis C virus (HCV), bacterial infections, and overdose) that are not addressed by PrEP. In contrast, SSP and MAT are more cost-effective. Consequently, to this point, PrEP has played no appreciable role in the declining HIV incidence among PWID.

The current opioid epidemic threatens decades of decline in PWID-related HIV

The current US opioid epidemic and the associated rise in injection drug use seem poised to reverse the decades-long downward trend in PWID-associated HIV incidence. The dramatic HIV outbreak among PWID in a rural Indiana county in 2015 underscores the rapidity with which HIV can spread among a PWID population that lacks risk reduction services, has high rates of needle and syringe sharing, and is densely networked [ ]. In fact, the spread of HIV among PWID in the Scott County, Indiana, outbreak was similar to the introduction of HIV among PWID in New York City in the late 1970s [ ].

Compared with 2001, the estimated prevalence of persons in the United States reporting past year heroin use has increased over fourfold [ ]. The opioid epidemic has been associated with sharp nationwide increases in injection drug use-associated endocarditis [ ] and hepatitis C infection [ ]. It seems inevitable that increases in injection drug use-related HIV transmission will follow. However, as of this writing, a clear change in course for injection drug use-related HIV transmission has not been observed through the most recent CDC HIV incidence estimates in 2015. However, harbingers of more PWID-related HIV transmission have been noted. For example, compared with the two prior years, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health noted a 48% increase in the number of individuals with newly diagnosed HIV attributed to injection drug use in the year ending August 2018 [ ].

The epidemiology of the current opioid crisis is starkly different from the inner-city concentrated heroin epidemics in the second half of the 20th century, in which African Americans were overrepresented. The current epidemic involves larger percentages of white individuals living in suburban or rural areas [ , , ]. It appears that prescription opioid abuse claimed a foothold in these areas [ ], with subsequent transitions to less expensive heroin, further complicated by widespread introduction of synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, into drug supply chains [ ], a major factor in sharply rising rates of opioid overdose mortality [ ]. Van Handel and colleagues from the CDC built a model to predict county-level vulnerability to rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV [ ]. Strong correlates for increased HCV/HIV transmission risk in a given county included higher prescription opioid sales, higher unemployment, and higher population percentage of white non-Hispanic individuals. The study highlighted 220 counties with risk scores in the top 5% of US counties: almost all were nonurban and highly concentrated in Appalachia, the Midwest, areas of New England, and areas in the Southwest—regions that also have the highest per capita rates of drug overdose deaths [ ].

The evolving epidemiology of opioid use disorder outside of major metropolitan areas is likely to further challenge an optimal public health response. After years of confronting the HIV epidemic among PWID, most large cities provide core services for PWID: SSP, MAT, and free testing for HIV and HCV. However, outside of metropolitan areas, such services are sparse to nonexistent. None of these evidence-based services was available in Scott County, Indiana, prior to the HIV outbreak among PWID there. As of March 2014, only 204 SSPs were known to be operating in the United States, and of these, only 29% served suburban or rural areas [ ]. In fact, at the time this survey of SSPs was conducted in 2013, there was only a single SSP serving four states that constitute the epicenter of the opioid epidemic: Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia [ ].

Treatment of HIV-positive people with opioid use disorder or who inject drugs

Stigma, barriers to retention, and limited access to ART

Since the introduction of effective combination therapy, HIV-positive PWID have faced stigma and barriers to HIV treatment [ ]. Underuse of ART among HIV-positive PWID is likely a function of several factors. First, active drug use is strongly associated with missed clinic visits and lapses in care [ ], reducing the opportunity to start ART. Second, a defining feature of addiction is the crowding out of typical concerns by the consuming need to obtain and use drugs. Third, many clinicians held negative views about people who use drugs and the utility of trying to treat them [ ]. Fourth, even clinicians who were amenable to treating PWID worried that inconsistent adherence to treatment would rapidly select for drug-resistant strains of HIV that would reduce future treatment options and risk transmission of resistant virus to others [ ]. In a community-based cohort study of 400 HIV-positive PWID conducted in Baltimore in 1997, half of the participants reported no ART use and only 14% were using combination therapy with a protease inhibitor, the optimal treatment at the time [ ]. In a survey of 764 persons attending an urban HIV clinic in 1998 and 1999, 44% of persons who reported active drug use had never used combination ART, compared with 22% of inactive drug users (abstinent >6 months), and 18% of nondrug users [ ]. More recent data show that delays in ART initiation persist for PWID compared with other groups [ ]. Among HIV-positive patients with opioid use disorder, engagement in MAT with methadone or buprenorphine stabilizes patients, facilitates engagement in care, and likely increases medical providers’ comfort in offering ART. In a cohort of PWID followed in Vancouver, Wood and colleagues reported that among 235 HIV-positive participants who had not been treated with ART at baseline, those who were receiving methadone maintenance treatment were twice as likely to initiate ART over 24-month follow-up [ ].

Direct biologic effects of opioids on HIV and immune function

There has long been interest in whether opioid use per se has direct effects on the immune system or HIV itself. This question retains relevance today given that the most effective MAT for opioid use disorder is based on long-acting opioid agonists [ ] and that opioid prescriptions for chronic pain are more common among HIV-infected persons than in the general population [ ]. Researchers have pursued this topic with in vitro studies, animal models, and analyses of human data [ ].

In vitro studies are best suited to characterizing mechanisms, but cannot account for complex system effects. Animal models have the potential to account for system effects, but may not reflect human processes accurately. In preclinical studies, opioids have been associated with decreased phagocytic function [ ], increased HIV-1 replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells [ ], and abnormal lymphoproliferative index and soluble markers of immune function [ ]. One study reported that opioids increased the viral replication rate in a primate model [ ]. Conversely, in a study that used a different primate model, long-term opioid dependency was associated with slowed progression of simian immunodeficiency virus and increased survival [ ].

Some clinical studies have reported associations that support the hypothesis that opioid use has direct biologic effects that adversely affect HIV natural history. However, clinical studies also face important limitations from confounding by socioeconomic status, psychological stress, adherence with treatment, survival bias, and PWID-associated coinfections (hepatitis C infection, tuberculosis, and bacterial infections). Additionally, opioid abuse is strongly correlated with use of other substances, including tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and stimulants (all of which have also been proposed to have direct effects on immune function or HIV pathogenesis [ ]). Consequently, unlike in controlled animal models, substance use by people is heterogenous and affords limited ability to ascribe observed associations to a specific drug or drug class. Despite these caveats, it is notable that several carefully conducted studies in the era prior to the availability of effective ART (which minimizes access to treatment and adherence as potential confounders) cast doubt on a major adverse biologic effect on HIV pathogenesis by opioids. Studies with long-term follow-up of HIV seroconverters found no difference in CD4 count trajectory (in the absence of treatment) in PWID and MSM [ , ]. Similarly, after accounting for sex differences and CD4 cell counts, another study found no difference in viral loads in HIV-positive PWID and MSM [ ]. A Dutch study of HIV-infected participants with documented dates of seroconversion found no difference in the time from seroconversion to an AIDS-defining condition in PWID and MSM, after excluding Kaposi’s sarcoma (which is much more common in MSM than PWID) and accounting for higher pre-AIDS mortality among PWID compared with MSM [ ]. Finally, a Swedish study of persons with documented HIV seroconversion even found that PWID were significantly less likely than MSM to progress to a CD4 count below 200 cells/μL, an AIDS-defining condition, or death from AIDS [ ]. These studies suggest that if opioids (or other abused drug classes) have direct adverse effects on immune function or HIV pathogenesis, the effect magnitude is not clinically meaningful.

HIV medication adherence and treatment outcomes

Substance use disorder is a reliable risk factor for poor HIV treatment outcomes. Early in the era of combination ART, an urban cohort study found that injection drug use as an HIV risk factor was the strongest predictor of failure to achieve viral suppression 12 months after initiating ART, with only 27% suppressed compared with 47% of non-PWID [ ]. Subsequent research clarified that poorer treatment outcomes among PWID were mediated by nonretention [ , ] and low medication adherence. In a nationally representative cohort collaboration that followed over 60,000 HIV-positive patients between 2000 and 2008, those with injection drug use as an HIV risk factor had 68% higher odds (95% confidence interval: 49%, 89%) of nonretention to HIV care [ ]. Wood and colleagues in British Columbia found that viral suppression rates following ART initiation among PWID lagged non-PWID by 20 percentage points. However, this difference disappeared when adjusted for adherence, calculated from medication refill data [ ]. Additional studies showed that history of injection drug use was not a monolithic risk factor for poor outcomes with HIV treatment. In fact, PWID who were abstinent or in substance use disorder treatment had HIV treatment outcomes that were indistinguishable from non-PWID [ , , ]. However, the effect of active drug use was profound. Arnsten and colleagues used electronic pill bottle monitors to quantify ART adherence in 85 current and former drug users, and found that average adherence was only 27% among active users, compared with 68% among former users [ ].

A longitudinal study emphasized the cumulative impact of drug use on HIV treatment outcomes. The study—which assessed 10-year restricted mean time in each care continuum stage following enrollment in an HIV clinic—found that PWID spent 17 fewer months on ART and virally suppressed, and lost 8.9 more months of life compared with non-PWID [ ]. Engagement in MAT is a mediator of improved treatment outcomes among HIV-positive persons with opioid use disorder [ , ]. A systematic review and metaanalysis found that MAT was associated with a 69% increased odds ART use, twofold increased odds of medication adherence, and 45% increased odds of viral suppression [ ].

But what about HIV-positive persons with active opioid use disorder (or another substance use disorder) who are not engaged in MAT? Early in the era of combination ART, active substance use was widely considered a relative contraindication to prescribing ART [ ]. However, clinical experience and observational studies show that some individuals with moderate to severe drug or alcohol use disorders do well on ART, although clinicians’ ability to predict who will do well was no better than chance [ ]. Moreover, a longitudinal study of HIV-positive people who use drugs (including opioids, cocaine, and methamphetamine), followed in seven HIV clinics and four clinical studies, found that abstinence, but also decreased frequency of drug use were both associated with increased likelihood of viral suppression during follow-up [ ]. These data suggest that achieving reductions in drug use, even without reaching abstinence, can translate into improved HIV treatment outcomes.

However, even clinicians who were open-minded about treating individuals who were actively using drugs worried about the emergence of antiretroviral drug resistance and the loss of future treatment options when a patient might accept substance use disorder treatment and be more prepared to commit to HIV treatment. In this regard, the arrival of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor-based regimens—beginning with ritonavir-lopinavir in 2000 and later with ritonavir-boosted atazanavir and darunavir—likely led to greater willingness to prescribe ART for those with untreated substance use disorder. While reasonably well tolerated and easy to take (particularly the later drugs) the key strength of these regimens was the extremely low emergence of resistance mutations with virologic failure due to nonadherence [ , ]. Consequently, and in contrast with nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase regimens that were also first-line treatment during this time, clinicians could offer treatment with boosted protease inhibitor-based regimens with little concern that early nonadherence would burn bridges for future treatment options. Currently, some integrase strand-transfer inhibitors (in particular dolutegravir and bictegravir) appear to have similarly high genetic barriers to resistance as boosted protease inhibitors, while also having a favorable side effect profile, low pill burden, and once daily dosing [ ].

HIV treatment gaps in PWID have slowly, but not completely, closed

Progress has been made in the past decade in reducing HIV treatment disparities among PWID compared with other risk groups. In a recurring survey of PWID in 20 US cities conducted by the CDC every 3 years, a recent report noted that current ART use among HIV-positive respondents in the survey increased from 58% in 2009 to 67% in 2012 to 71% in 2015 [ ]. Similarly, in a cohort study examining trends in the HIV care continuum in a large clinical cohort in Baltimore, Lesko and coworkers reported that differences between PWID and non-PWID in retention to care, receipt of ART, and viral suppression diminished between 2001 and 2012 [ ]. For example, in 2001, the estimated viral suppression rates in PWID and non-PWID were 28% and 42%, respectively. However, by 2011 substantial temporal improvements were noted in both groups and the gap between PWID and non-PWID had nearly closed, with viral suppression rates of 69% and 71%, respectively.

Interventions to improve HIV care continuum outcomes among persons with substance use disorders

Strategies to improve treatment outcomes among people with HIV and substance use disorders have been assessed in randomized controlled trials ( Table 5.2 ). Interventions have included patient navigation, integrated (substance use and HIV) care models, incentives, and directly observed therapy (DOT) for HIV. HPTN study 074, which was conducted in Ukraine, Vietnam, and Indonesia, found that an intervention comprising systems navigation and psychosocial counseling significantly increased use of ART, viral suppression, and use of MAT, compared with the control condition [ ]. Additionally, cumulative mortality was 53% lower (95% CI; 10%, 78%) in the intervention arm compared with control. In contrast, Metsch and colleagues reported that a 6-month patient navigation intervention that targeted hospitalized persons with HIV and substance use disorder was not associated with improved survival with viral suppression compared with usual care [ ].