Opioid use disorder and endocarditis

The increasing use of opioids over the past decade has resulted in a crisis of overdose and death in the United States that has also been accompanied by an increase in infectious complications related to injection drug use (IDU). It has been well described in the medical literature that there is an increased risk of hepatitis C and HIV infections in people who inject drugs (PWID) [ ], even if knowledge gaps related to these infections exist among PWID [ ], but the dramatic increase in endocarditis secondary to IDU has been striking to those who practice in regions of the country affected by the opioid epidemic. Providers are seeing this entity with great frequency [ ], and treating endocarditis in this population has unique challenges that if not addressed, it may impact the ability to be successful with treatment. This chapter will attempt to identify the specific issues related to the populations of patients with endocarditis secondary to injecting opioids and aims to provide strategies to address the unique issues inherent in this group of patients to ensure the best possible clinical outcome.

From an epidemiologic perspective, it remains difficult to estimate the number of cases of infective endocarditis (IE) related to IDU. It has been estimated there are 3–10 cases of endocarditis per 100,000 people and that the number of cases of IE overall is up to 50,000 cases per year in the United States [ ], with an increasing proportion of those cases secondary to IDU [ ]. Given the ongoing national health crisis secondary to opioid use disorder (OUD), it is likely that the total number of cases is on the rise. And while overdose deaths from drug use, and opioids in particular, are rightfully identified as a national public health emergency, our inability to characterize the true impact of serious infections related to IDU on these patients mitigates our ability to grasp the vast extent of this healthcare crisis. These infections, seemingly rising to rates unforeseen previously, represent a highly morbid and potentially lethal health condition that requires prolonged antibiotic therapy and often results in cardiac surgery for valvular repair. Failure to address the underlying substance use disorder in these patients, specifically OUD, is a common occurrence leading to possible reinfection from continued IDU or death after hospital discharge from drug overdose. We will review the epidemiology of endocarditis in persons who inject drugs, the treatment strategies to cure these infections, and the opportunities to engage with these patients while hospitalized to potentially initiate a plan to engage them in OUD treatment.

How does endocarditis occur in PWID?

Endocarditis has long been known to be a consequence of IDU with many studies dating back at least to the 1950s describing the increasing rates of infections due to IDU, with a focus typically on right-sided endocarditis given the frequency of these cardiac valves being involved [ ]. The risk of infection in these individuals is multifactorial and relates to the drug product, the practice of injection itself, and the susceptibility of the host ( Table 8.1 ).

| Contaminated drug product | Spore-producing organisms including Clostridium spp. Fungi including Candida spp. Bacillus spp. Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Adulterated drug product

| Talc Baking soda Acid |

Unsterile water

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa Burkholderia spp. Other gram-negative organisms, including anaerobes |

Oral flora

| Streptococci Candida spp. HACEK organisms a Anaerobic organisms |

| Skin flora | S. aureus Streptococci Coagulase-negative Staphylococci Polymicrobial |

| Host impaired immunity | Hepatitis C HIV Potential opioid-induced immune response reduction |

a Haemophilus spp., Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella kingaote

The pathology of endocarditis results in the establishment of bacteria on the cardiac valves but the initial structural abnormality of the cardiac valve is typically a sterile vegetation composed of fibrin and platelets to which bacteria adhere [ ]. The proposed mechanism of disease begins with impurities in the heroin or drug product that may damage the cardiac valves (or the valves already have preexisting abnormalities) through repetitive injury to the tricuspid valve causing endothelial damage as this is the first valve to encounter the foreign material when injecting into the venous system [ ]. Aside from causing direct mechanical damage, injected diluents can cause vasospasm and damage to the intima layer of the endothelium, leading to thrombus formation and platelet aggregation [ ]. Different organisms have been reported to affect valves with differing frequency [ ] due to the propensity of the individual bacteria to adhere to damaged valves and subsequently colonize this inflamed endothelium producing cytokines and tissue factor which serves to recruit monocytes and platelets [ , ].

The process itself of injecting heroin, for example, is complex and comes with attendant risks at different stages of the injecting process. There are many different factors that are at play both with respect to the effects of heroin and other impurities on the ability of the individual to clear bacteria as well as the actual process of injecting opioids can result in the introduction of bacterial or fungal pathogens leading to disease.

Opioids are often “cut” with impurities which refers to substances added to increase the weight of the drug product being sold but often does not necessarily contain an active drug (although, the addition of synthetic fentanyl to heroin is likely responsible for many overdose deaths in this current epidemic [ ]). These impurities such as talc or baking soda, when injected, may cause local vascular injury which, in conjunction with poor skin antisepsis, can lead to localized or systemic infection. Heroin that is adulterated in this fashion may be limited in its potency requiring the person to inject with greater frequency, enhancing the potential of infectious complications. In addition, the opioid may not have been produced in a sterile fashion and there have been reports of heroin contaminated with spore-producing bacteria [ , ], leading to well-described outbreaks of severe infectious complications of IDU [ ].

The typically solid preparation of the heroin product is subsequently dissolved often with the use of a spoon or an aluminum can in the presence of water and/or heat. The source of the water may range from sterile water to water from a toilet and with it the organisms that may become intermixed with the opioid preparation will then be injected [ ]. Infections that result from gram-negative bacteria that live in water sources have been well described [ ], and the possibility that these organisms are present needs to be considered when treating individuals empirically for life-threatening bacterial infections.

Candida species and other fungi are a relatively rare cause of IE but well known to occur in PWID [ , ] due to environmental contamination. Recent reports from both Denver, CO, and Massachusetts [ , ] point to Candida species increasing in frequency in this population as a cause of both fungemia and endocarditis. Also, syringe tips often will be put into the mouth of the individual prior to injecting for multiple reasons such as habit, to test the drug prior to injecting, or to ensure that the bevel of the needle remains sharp [ ]. This has the potential to introduce mouth pathogens into the bloodstream once the syringe is introduced [ ] into the vein or skin. In addition, a sterile site is often not prepared on the skin with the use of an alcohol pad, and with any penetration of the skin by use of an injectable device can lead to infection typically with skin pathogens, mostly prominently Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcal species of bacteria.

In addition to infectious agents being introduced through injecting drugs, opioids have been demonstrated to affect the immune system broadly as organs and tissue throughout the body contain opioid receptors, not solely limited to the central nervous system, suggesting a greater overall role in human health. In vitro data suggest opioids have broad effects on all aspects of the immune system including both adaptive and innate immunity [ ], but the research is far from conclusive to suggest either a clear detrimental or beneficial effect on overall immune health [ , ]. While case series and cohort studies have suggested an increased risk for certain infections [ ], more rigorous studies will need to be undertaken to determine the interplay between opioids and the immune system, the impact of length of opioid treatment on these immune effects, and whether all opioid analgesics have the same properties with respect to immune activity.

The host may be uniquely susceptible to bacterial infections as hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody positivity is seen in roughly 70% of PWID, and the majority of these individuals likely have active disease without having cleared the infection [ ]. While it is unclear to what degree these individuals with HCV are at increased risk for serious bloodstream infections or endocarditis, HCV does appear to represent an additional risk for S. aureus infection [ ]. In those select individuals with HCV and resulting cirrhosis, their immune function will be compromised in various regards, but characteristically they will have more complications from infection than healthy individuals given defects in innate immunity, phagocytosis, and impaired humoral immunity [ ]. Increasing numbers of HIV infections have been seen in different areas of the country [ , ] with the outbreak of HIV infections in Scott County, IN [ , ], being the most dramatic demonstration of an HIV infection cluster related to IDU. Obviously, HIV infection has long been seen in individuals with a history of IDU, and serious bacterial infections which occur in individuals with HIV which can result in endocarditis [ ]; however, the risk of serious bacterial infections can be mitigated with early antiretroviral treatment [ , ].

Increasing rates and epidemiology of infective endocarditis secondary to injection drug use

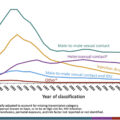

Several recent studies [ , ] have clearly demonstrated that the rates of endocarditis secondary to IDU have increased over the past 15 years, all of them showing dramatic increases that coincide with the national opioid epidemic [ , ]. In fact, the sharp increase in cases of endocarditis could serve as a method to mark this new epidemic of IDU as an increase in endocarditis seen in the early 2000s was associated was associated increase in positive opioid toxicology and new HCV infections [ ]. There remains, however, a limited ability to capture exact number of cases of endocarditis related to IDU given the dependence on discharge data or the use of surrogate markers for IDU such as hepatitis C status [ , , ] given the lack of an International Classification of Disease (ICD)-9 or ICD-10 code for IDU and no reporting requirements at either the state or national level which could provide actual numbers of patients with this condition. In addition, gaps in recording data fail to account for long-term morbidity, for example, when a patient suffers a devastating embolic stroke from IDU. Regardless of the failure to systematically capture the number of cases of endocarditis, the number of cases certainly is increasing anecdotally and in the available medical literature, and the total numbers of cases that are being discussed likely represent an underestimation of the real number of infections.

An increase in hospitalizations for IE in PWID was seen by Wurcel et al. with 12% of admissions for endocarditis at community hospitals were secondary to IDU in 2013 compared with 7% in 2000 [ ]. Similarly, in North Carolina, annual hospitalizations for IE associated with IDU increased from 0.92 to 10.95 per 100,000 persons between 2007 and 2017 using data gathered from hospital discharges [ ] and in a national survey based on hospital discharge data, endocarditis secondary to IDU increased from 15.3% to 29.1% of IE cases between 2010 and 2015 [ ].

The incidence of S. aureus infections has increased over the last half-century worldwide and this pathogen is the most common cause of IE in developed countries, with the incidence of S. aureus infection being even greater in those with IE from IDU, with well over half of the cases in PWID being due to S. aureus [ , ], far greater than in those who do not inject drugs. Infection with S. aureus puts patients with IDU-IE at increased risk of severe sepsis, multiorgan dysfunction, major neurological events, and death [ ] given the higher rates of vegetations > 1 cm and extracardiac emboli compared with non-IDU patients. Other gram-positive organisms besides S. aureus , gram-negative bacteria, fungal organisms, and polymicrobial infections all have been shown to cause endocarditis in this population[ , , , ].

The International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study (ICE-PCS) investigators found most cases of IE in a pooled international population involve vegetations on either the aortic (38%) or mitral valves (41%) compared with the tricuspid valve (12%) [ ]. However, in those individuals with IDU-related endocarditis, a far higher percentage of them have right-sided disease [ , ]. The mechanism behind this phenomenon remains elusive [ , ]. But, more recently, right-sided endocarditis is by no means the exclusive presentation for those with IDU-associated endocarditis as several studies have demonstrated a relatively high rate of left-sided involvement as well in individuals who inject drugs [ , , , , ]. Historically, there were more men than women with IE secondary to IDU [ , ], and while this seems to continue to be the case, the gap is narrowing as there is an increase in the number of women with this condition [ , ], a fact that is likely trending with the increase in women who use opioids [ ].

IDU-associated endocarditis: diagnosis and treatment

Persons who inject drugs are at high risk for bloodstream infections, and early recognition and diagnosis of endocarditis is paramount to potentially mitigate sequelae of the infection. Individuals presenting with fever and with a history of IDU should be strongly considered as possibly having a bloodstream infection with the need to rule out endocarditis. The early treatment of this condition may prevent complications such as the development of a paravalvular abscess, embolic phenomena, or possibly valve destruction that may require a surgical intervention in order to treat.

The diagnosis relies on the use of the universally accepted, modified Duke criteria ( Table 8.2 ) [ , ] that include major and minor criteria to categorize cases as definite, probable, or unlikely IE, and this well-accepted method has been shown to retain its accuracy in diagnosing endocarditis in PWID [ , ]. Two to three sets of blood cultures, ideally drawn prior to the administration of antibiotics, with each blood culture drawn from a different anatomical site, provide the greatest yield with respect to determining the organism responsible for the condition. Obtaining blood cultures can be very difficult at times in PWID due to sclerosis of veins secondary to the frequent injection of intravenous (IV) drugs, and this difficulty in obtaining blood cultures risks contamination. An echocardiogram to look for valvular vegetations is included in the modified Duke criteria with additional criteria including fever, elevated inflammatory markers, and recovery of an organism that is a typical cause of endocarditis. The diagnosis of endocarditis can be challenging but given that PWID are at significant risk for this condition, ongoing evaluation needs to continue. Transthoracic echocardiogram is often applied as the first modality to evaluate for valvular lesions and if negative, a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is often required to detect infection involving a cardiac valve.

| Major criteria | Blood culture positivity

| |

| Minor criteria | Predisposition to IE

| |

| Fever >38°C/100.4°F | ||

Vascular phenomena

|

| |

Immunologic phenomena

|

| |

Microbiologic evidence

| ||

| Definite IE | 2 major criteria OR 1 major + 3 minor criteria OR 5 minor criteria | |

| Possible IE | 1 major + 1 minor criteria OR 3 minor criteria | |

In individuals who have continued bacteremia, but no clear evidence of endocarditis on initial TEE, a repeat TEE 5–7 days after the initial study is recommended [ ]. Once the diagnosis of IE is made, treatment decisions can follow largely well-accepted treatment guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA), the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), and the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC) [ , , ].

Treatment of IDU infective endocarditis

Empiric treatment of IE in patients who have endocarditis, or bacteremia with a concern for endocarditis, needs to account for the likely pathogens. Therefore, it is important that broad antibiotic therapy to cover gram-positive pathogens (particularly methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive S. aureus given the highest likelihood that S. aureus is the causative agent), but also empiric treatment for gram-negative bacteria, including Pseudomonas [ , ], is initiated in the population of patients who inject drugs. This would be a necessary expansion of typical empiric coverage for those who do not inject drugs which may not be as broad with respect to the gram-negative coverage. While empiric treatment is determined on a case-by-case basis, regimens such as vancomycin and either meropenem, a third or fourth generation cephalosporin (ceftazidime or cefepime), or an extended spectrum beta-lactamase inhibitor with activity against Pseudomonas provide the requisite broad antimicrobial therapy in this setting.

Each of the IE guidelines has addressed the topic of empiric antimicrobial treatment slightly differently. The AHA approach to empiric treatment has a statement that simply recognizes that therapy initially is usually broad, will likely be narrowed, and infectious diseases consultation should take place at the time of the initiation of empiric antibiotic therapy. The BSAC guideline provides explicit recommendations for native valve, empiric treatment for endocarditis in an individual who injects drugs and is septic which includes vancomycin dosed as per local guidelines and meropenem 2 g intravenously q8h to cover staphylococci (including methicillin-resistant staphylococci), streptococci, enterococci, HACEK, Enterobacteriaceae , and P seudomonas aeruginosa . The ESC recommends that consideration be given to the type of drug and solvent used as well as the infection location, while ensuring that S. aureus is covered. If the patient is injecting pentazocine, Pseudomonas is emphasized as a potential pathogen and must be included as a target of empiric treatment due to outbreaks of this pathogen [ ], while if brown heroin was injected, Candida spp. should be covered [ ].

Once the microbiologic diagnosis of IE has been established in PWID, the treatment is antibiotic therapy typically for 4 to 6 weeks with much of the historical data suggesting this should be parenteral therapy. The guidelines again provide similar detailed guidance that is organism specific with the most common causative agents in this population in both those with native and prosthetic valves.

Surgical interventions

Surgical indications for IE have been developed and assessment by the surgical team should occur early in the course of a hospitalization and with IE, surgery occurs in up to 50% of the patients affected [ ]. The generally defined indications for which prompt evaluation and consideration for cardiac surgery are listed in Table 8.3 . These include large valvular vegetations, valve rupture, paravalvular abscess, difficult to treat organisms, new embolic phenomena despite appropriate treatment, and heart failure that fails to respond to medical therapy.

Heart failure

| Severe regurgitation causing refractory cardiogenic shock or pulmonary edema Fistula into a cardiac chamber or pericardium causing refractory cardiogenic shock or pulmonary edema |

| Uncontrolled infection | Increase in vegetation size despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy Infection caused by fungi or drug resistant bacteria Persistent fever and positive blood cultures >7–10 days |

| Prevention of embolism | Persistent vegetation after systemic embolization Anterior mitral leaflet vegetation, particularly with size >10 mm ≥1 Embolic events during first 2 weeks of antimicrobial therapy |

| Perivalvular extension | Valvular dehiscence, rupture, or fistula New heart block Large abscess or extension of abscess despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy |

The decision to intervene surgically in patients with endocarditis is often reached through a multidisciplinary approach involving the cardiothoracic surgical team, internal medicine providers, and cardiologists, taking into account the risk of the surgical procedure and weighing the benefit that the patient is likely to experience from the procedure.

The ESC IE guidelines specifically include recommendations regarding surgery in PWID as it relates to right-sided endocarditis [ ]. They suggest that avoiding surgery for this condition is advised given the risk of relapse related to opioid use and the chances of recurrent infection. These guidelines are consistent with US practice as clinical data support the relative infrequency of the necessity of surgical intervention for right-sided endocarditis as it is successfully medically managed in the vast majority of cases.

Timing of cardiac surgery for endocarditis

There has been a great deal of discussion in the medical literature about the appropriate timing of surgery for endocarditis [ ]. Several studies have demonstrated that early surgery is not associated with worse clinical outcomes and the US and European guidelines suggest there is no need to delay surgery in general once an indication for early surgery has been identified [ , , ]. Even in patients with ischemic stroke, several studies have suggested that there is no apparent survival benefit in delaying surgery [ , ].

However, surgery will often be delayed when there is evidence of a large cerebral infarction or a hemorrhagic stroke given concerns for neurological compromise. Patients can bleed into the infarcted areas of the brain [ ] or further bleed into the hemorrhage with the use of the cardiac bypass machine and the anticoagulation associated with that procedure. Much of the medical consensus currently suggests waiting at least 2 weeks and ideally up to four before considering surgery in patients with large cerebral infarction and for at least 4 weeks in those with intracerebral hemorrhage if possible [ , ].

In the patient with OUD, it would be expected that the timing of surgery would be consistent with those who do not inject drugs given that the recent thoracic surgery guidelines for the treatment of IE that suggest the same criteria are used for determining surgery whether the patient has a history of IDU or not [ ]. While right-sided disease is successfully treated medically most of the time, stable patients with OUD with large emboli or stroke will occasionally be discharged from the hospital with the plan to complete much of their IV antibiotic therapy only to return at a future date for a planned cardiac surgery procedure. This may be a chance to engage the patient with treatment for their OUD prior to their surgery. Delays for other reasons, including not performing surgery until the patient engages in treatment for OUD, are sometimes considered without data supporting that this strategy motivates patients to engage in OUD treatment, and may not benefit either the patient’s cardiovascular health or in overcoming their OUD.

Outcomes with surgery

Short-term clinical outcomes after surgery are supported by a recent metaanalysis of 13 studies that evaluated the 30-day mortality in patients who receive cardiac surgery for IDU-related endocarditis and demonstrated it is no different than surgical outcomes in those without drug-use associated endocarditis [ ]. However, there are poor long-term health outcomes in patients with OUD who have surgery as part of their treatment for endocarditis with high 1 year mortality rates up to 22.5% in one study of 64 patients [ ], while another had a 5-year mortality rate of 41% [ ].

These high mortality rates are striking when considering the few medical comorbidities in these patients compared with the noninjecting endocarditis patients [ , ]. The reasons for this finding are possibly related to the severity of the disease, the aggressiveness of S. aureus (the organisms most likely to be responsible for endocarditis in OUD), late presentation to care, or possibly other unidentified factors. But, the far more likely driver of these poor outcomes is the recurrence of active drug use, subsequent reinfection and endocarditis, or even overdose death. Several studies have demonstrated that continued drug use after hospital discharge leads to frequent recurrence of infection, higher risk of valve complications, and overall higher mortality than expected for this cohort [ ]. These data support both that necessary surgery should not be denied in PWID due to concerns about short-term clinical outcomes, but in addition, the postsurgical care addressing substance use should be considered to be one of the most important aspects of the comprehensive postoperative and long-term future care.

Data reporting on the impact of inpatient treatment of OUD while inpatient for the treatment of endocarditis on reducing morbidity and mortality are limited. One recent study however has demonstrated mortality benefit in patients who were able to be treated for their OUD while hospitalized [ ]. While the numbers of patients who were treated for their OUD was small (only 40 out of 202), a statistically significant improvement in mortality was seen, and this represents one of the first clear examples of a hospital-based intervention for treatment of OUD in endocarditis.

Controversies regarding surgery

Surgical indications are fairly consistent for the treatment of endocarditis from both the US and European guidelines [ , ]. However, there can be barriers to surgery that relate to the underlying OUD with decisions made about surgery on occasion based on an individual provider’s opinion about performing what they might consider to be futile care. The cardiovascular surgery guidelines state that “Although operative risk is not higher, drug-addicted patients have a greater probability of death in the year after operation than do nonaddicted patients. The injection drug use must be included and weighed in decision-making, and patient treatment must include drug rehabilitation [ ].” This topic has been the subject of both the lay press and the medical literature as society struggles to grapple with ethical issues about providing care that is costly and often unsuccessful unless the underlying OUD is addressed, with questions being asked about how much care is too much given the cost and poor outcomes in many cases [ , ].

The care of a patient who has developed IE undoubtedly is best done with a team approach, particularly when surgery is necessary. An editorial accompanying the latest guidelines from cardiothoracic surgery (and a letter in response) regarding when to perform surgery commented specifically on the individual with IE from IDU [ , ]. The author rightly suggested that the use of addiction services within the hospital setting prior to the surgery with a plan to support the patient in their recovery both from the surgery and substance use disorder. However, the suggestion put forth that there is value in creating a contract between the surgeon and patient that outlines in advance that another operation may not be offered should the individual continue to engage in substance use is not based on data and represents bias some patients with OUD face even within the medical system. It is purported that a contract will provide “additional motivation to remain ‘‘clean’’ and can assist in decision making if reinfection occurs [ ].” Similar contracts are not given to diabetics who are unable to manage their blood sugar or smokers who cannot stop smoking [ ], other challenging health conditions where individual behaviors can have significant and poor consequences. More emphasis needs to be placed on trying to address the barriers that prevent the patient with OUD from achieving meaningful recovery.

A response providing the surgeon’s perspective argued that just as antibiotics are required for treatment of endocarditis, addiction treatment is of equal importance [ ]. While asking the patient to sign a contract may not be evidence-based, it can provide a tangible effort to show the importance of the dual nature of the care that is required. And, “the reassurance that surgeons need and are entitled to is that the patient with SUD has been evaluated by an addition medicine expert, addiction treatment is available and offered, and the patient has agreed to make a good faith effort [ ]…” Efforts need to be universal to address addiction in this setting so that both the surgical issue and the underlying cause of that issue can be addressed.

The decision to considering limiting surgical interventions in patients with OUD has been likened to the approach that has been taken over the years with individuals who need a liver transplant. For example, a patient who has cirrhosis from underlying alcohol use disorder often will not be listed for a liver transplant unless they have been able to demonstrate a period of being alcohol-free. This selection process allows for the transplanted liver to be given in situations that are most likely to result in a successful transplantation, as livers to be transplanted represent a finite resource. In many situations, surgeons will operate on individuals during the first admission for endocarditis, but oftentimes a second surgery will not be undertaken [ ].

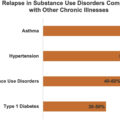

Counter arguments to the approach of limiting surgical options in PWID recognize that, unlike procurement of livers for transplantation, cardiac valves do not represent a finite resource. And while it is a technically challenging procedure that is costly [ ] and may expose healthcare personnel to risk including acquisition of viral infections such as HIV or hepatitis C, we as a society have not limited surgical care when it is obviously beneficial for other illnesses, such as cancer, which also has recurrence, and is many times related to substance use behaviors such as nicotine or alcohol. Our inability to provide a pathway toward meaningful OUD treatment often represents a failure of the healthcare system as it does not address the complex medical needs of patients with OUD. In addition, like many chronic medical conditions, OUD is characterized by periods of success/relapse, and while relapse in this situation can lead to serious infections such as endocarditis or prosthetic valve endocarditis, it does not represent a reason to no longer engage the person in care, which in many circumstances is life-saving care.

Some cardiac surgeons have taken the approach that waiting until the person has agreed to OUD treatment and has been successful in those efforts is the best strategy in patients who otherwise are clinically stable and whose surgery can be delayed. This approach may be an acceptable strategy in some individuals but in others, it may in fact be arbitrarily applied. Clearly, if this approach is to be taken, a robust program engaging the person in OUD treatment while in the hospital needs to be enacted, and many such programs do not exist at this time. An aggressive approach that allows for optimal treatment of both the infection and OUD is the ideal strategy to care for these patients [ ] but developing such a system remains challenging, and while many hospitals are developing comprehensive teams to assist with these complex patients, this level of care is not yet universal, and therefore guidelines that force patients to start OUD treatment prior to receiving life-saving medical care cannot be universally or equally applied.

Location to receive parenteral antibiotics

Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) allows patients the opportunities to be treated outside the hospital (at a skilled nursing facility or at home) for their extended course of antibiotics. There are opportunities for cost savings as patients do not need to remain in the acute care setting and a return to a more normal life in familiar surroundings while still being treated appropriately for a severe infection. It is not, however, without challenges as laboratory and clinical monitoring needs to be coordinated with service providers who may be outside of the hospital network. In one study, 33% of individuals discharged from two different academic medical centers experienced an adverse event during OPAT when being treated for complicated S. aureus bacteremia, with over 60% of those complications resulting in rehospitalization [ ]. These data demonstrate that OPAT is a challenging endeavor for patients and there may be burdens unique to the OUD population requiring even greater resource utilization to be successful with OPAT, but there remains a significant bias at this time against even making OPAT available for these patients.

Many providers, healthcare systems, and visiting nurse companies do not allow for patients who inject drugs to safely return home with a peripherally inserted central venous catheter or a midline catheter for administration due to the risk of possible manipulation of the catheter for drug use. This results in the requirement in many circumstances that they entirety of IV antibiotics occur either in the hospital or in a facility that can monitor them. A survey of over 500 Infectious Diseases providers suggested that the majority of patients are treated for IE either in the hospital or an extended care facility for the entirety of their antibiotic course [ ] which represents an incredible burden on both the inpatient and outpatient facilities and likely adds additional costs that must be absorbed by the medical system. A separate survey demonstrated that 95% of inpatient providers would consider using OPAT for patients without IDU, but if the patient is a PWID, that number dropped to 29% [ ]. The most common barriers to discharging a patient with IDU on OPAT were socioeconomic factors, willingness of infectious diseases physicians to follow as an outpatient, and concerns for misuse of peripherally inserted central catheters and adherence with antibiotic treatment. This results in many younger patients being asked to stay in a facility for many weeks, often after they are well enough to return home, simply for the administration of IV antibiotics. This additional burden of keeping patients away from their families or out of work increases stress and creates financial hardships on many occasions. It can add to the complex psychological issues that many patients with OUD are experiencing.

It is not clear that parenteral antibiotics need to be administered in a monitored setting for this patient population nor is it obvious that this significantly improves clinical outcomes compared to allowing patients to return home for the completion of their therapy. The concern that an indwelling catheter will be utilized by the PWID as a means of injecting drugs seems plausible, but data from several studies do not support that this happens in great numbers when OPAT is done with close supervision [ ], nor is it clear that rates of access of IV lines is higher as an outpatient than in patients who are in a skilled nursing facility for the entirety of their antibiotic course [ ]. The truth is likely that people will find ways to use drugs if they are so inclined whether an IV catheter is in place or not. No study has directly compared strategies for OPAT comparing those who use drugs and those who do not, nor does a study exists allowing patients to be randomized to different arms such as inpatient versus going home, with treatment provided for both their infection and OUD; data which are sorely lacking.

One recent study identified retrospectively hospitalized PWID, with IDU in the preceding 2 years, who were discharged with the need to complete at least 2 weeks of parenteral antibiotics which were being monitored by an OPAT program. Persons who inject drugs discharged home were not more likely to have complications than those discharged to an SNF/rehab [ ]. Another study of 29 PWID who presented to an infusion center for daily antibiotic infusions reported success in that no patients were suspected of manipulating their PICC line. However, these patients were carefully selected and a seal was used over the PICC line that would be able to identify if the line was tampered with, but represents an alternative that needs to be considered in appropriate patients [ ]. This decision in some cases is made by the treating provider as it is deemed to be in the patient’s best interest; however, in other situations, there are no options as many home infusion companies may have developed policies that preclude them from giving antibiotics at home to a patient with a PICC line and a history of IDU. These decisions are not based on data and, there are significant gaps in the data about safe strategies that allow PWID to be discharged with a PICC line [ ].

Other treatment issues

Short-course treatment options for right-sided endocarditis

Short-course treatment options for right-sided endocarditis were sought given the frequency of right-sided endocarditis in PWID and the above-mentioned challenges with parenteral antibiotics in this population. Several studies from the early 1990s demonstrated that 2 weeks of treatment for strictly right-sided endocarditis can be effective. Reports of three prospective, nonrandomized clinical trials support the use of a 2-week course of a penicillinase-resistant penicillin and an aminoglycoside antibiotic to treat uncomplicated, exclusively right-sided endocarditis caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) in PWID [ ].

A subsequent study of 90 consecutive individuals with IDU and right-sided MSSA endocarditis randomized individuals to a regimen of cloxacillin alone or cloxacillin plus gentamicin. Treatment was successful in 34 of the 38 patients who received cloxacillin alone and 31 of the 36 patients who received cloxacillin plus gentamicin. Of the 37 patients who completed 2-week treatment with cloxacillin, 34 were cured and 3 needed prolonged treatment to cure the infection (1 patient died during treatment) which was equivalent to the group that received combination therapy. However, with the increasing data demonstrating that even low-dose gentamicin for a short period of time is associated with significant renal toxicity [ ], the recommendation now for individuals who are candidates for short-course treatment for right-sided IE with MSSA is for the β-lactam antibiotic alone. It remains incumbent on the provider who is opting for a short-course regimen to continue to be vigilant that these patients remain uncomplicated with respect to their right-sided disease as there may be need for extension of therapy if complications ensue.

Long acting IV options

Dalbavancin and oritavancin have been approved for the treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections and represent two novel agents that are unique in that they have extremely long half-lives [ ]. This allows infrequent administration of these medications while still achieve therapeutic drug levels. These novel lipoglycopeptides were approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSIs) and have activity against several gram-positive pathogens, including methicillin-resistant and vancomycin-intermediate susceptible strains of staphylococci and viridans group and β-hemolytic streptococci , Streptococcus pneumoniae , Enterococcus species, and anerobic gram-positive cocci and bacilli [ ].

This has a great deal of appeal to providers caring for people with OUD given the concerns about long-term IV access. However, there have already been reports of treatment failures with this approach and caution is therefore advised [ ]. It is likely that decisions will need to be made on a case-by-case basis, weighing the risk versus benefits. The largest study to date that suggests that this strategy may have promise required most patients to complete a standard treatment regimen through the period of bacteremia prior to changing to dalbavancin [ ]. More clinicians in practice have resorted to using these medications for the treatment of endocarditis [ , ] particularly after the initial recommended IV therapy has been given while bacteremic. It is unclear if there will be randomized studies to support the use of long-acting glycopeptides for the treatment of endocarditis in individuals with or without IDU. A randomized trial had been planned to address this question in patients without OUD but was discontinued in 2017 by the sponsor after only enrolling one participant [ ].

Dilemmas for treating providers—is oral therapy for endocarditis an option?

Not infrequently, the ID provider is asked to provide recommendations for oral therapy to the primary team caring for a patient who is otherwise clinically stable, and perhaps well into their IV antibiotic treatment for endocarditis. This often occurs because the patient is not being appropriately treated for their OUD while hospitalized, and does not want to stay hospitalized for an extended course of IV antibiotics while in withdrawal. It becomes very challenging to practice medicine where a provider must attempt to provide a treatment regimen that is effective but does not conform to current treatment guidelines; however, there are some minimal data to help guide potential decisions.

Recently, a trial was published that provides preliminary data to support switching to oral antibiotics in very stable individuals with left-sided IE. In the Partial Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotic Treatment of Endocarditis (POET) trial [ , ], individuals with left-sided IE were randomized to continuing IV therapy versus changing to highly effective oral antibiotics after they had been stabilized on at least 10 days of IV therapy. The trial found that oral therapy was noninferior to IV therapy with respect to incidence of clinically relevant embolic events, cardiac surgery, and bacteremia relapse, while the oral antibiotic group also had fewer deaths. The causes of the endocarditis were streptococcus species, Enterococcus faecalis , S. aureus , or coagulase negative staphylococci. Of note, there were no individuals with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and only 5 of the 400 participants in the study were PWID. Further considerations that may temper the enthusiasm for this strategy in PWID were the frequent visits required to the ID clinic over the course of the study and that several antibiotics used in the study are not available in the United States. However, once patients were randomized to the oral treatment group, they only remained in the hospital for 3 days compared with 19 days in the IV group, a definite appeal to many patients with OUD. While the results are certainly encouraging, further research will be required to evaluate this strategy. It will definitely provide some reassurance to providers who often are forced to consider alternative treatment strategies in patients with OUD [ ]. These data can serve as one strategy when the clinical situation does not allow for guideline-based decision-making.

Two studies have evaluated the use of predominantly oral 4-week antibiotic regimens (featuring ciprofloxacin plus rifampin) for the therapy of uncomplicated right-sided MSSA IE in PWIDs. In each study, including one in which >70% of patients were HIV seropositive, cure rates were >90% [ , ]. While the relatively high rate of quinolone resistance in S. aureus isolates found today may make this strategy problematic, it does provide additional strategies to consider when providers are in situations where they must choose oral alternatives for treatment of this serious condition, which is preferably treated with IV therapy.

Retreatment of PWID with recurrent episodes of endocarditis

PWID who present with repeat infections is an unfortunate reality related to the relapsing-remitting nature of the underlying OUD. However, it also represents another opportunity to engage with patients whose overall poor health outcomes are most likely attributable to their ongoing OUD. Data from one hospital demonstrated that engagement with addiction services or psychiatry was less likely to occur with recurrent admissions perhaps reflecting perceptions of futility in trying to address addiction [ ]. It is imperative that the retreatment of these individuals, even repeat surgical intervention, needs to be undertaken more systematically given the high-risk nature of this group. It should be expected that there will be relapses to drug use given the natural history of OUD, and health systems need to engage in longitudinal care of these patients with the chronic medical condition of OUD.

Addiction treatment for hospitalized patients: an opportunity to intervene

Failure to address OUD in hospitalized patients

IE cannot be disconnected from the disorder that led to the infection—IDU due to OUD. However, the failure to address OUD reliably, or connect patients to appropriate long-term follow-up, has been demonstrated in studies focused on endocarditis [ , ], as well as in PWID admitted to the hospital for any reason [ ]. A major opportunity has been missed in the past, but engagement must ensue now in order to stem this current crisis.

Hospitalization as opportunity to intervene in OUD

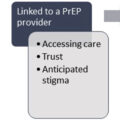

There are increasing calls from a broad range of stakeholders to consider the hospital setting a time to engage patients to get started on OUD treatment [ ]. While it is abundantly clear that treatment for OUD will require a longstanding relationship with a team of providers in an outpatient setting [ ], opportunities abound to engage patients in all areas of the hospital to begin treatment. In emergency departments, research has suggested that brief interventions and initiation of buprenorphine treatment, either during the limited stay in the emergency department or a home-based buprenorphine induction, can lead to increase linkage to care over the following 30 days [ ]. The success of this intervention has led to some states legislating that the referral or treatment of OUD be routine for all emergency departments [ ]. As with all the interventions for OUD, the key is reliable linkage to care after patients are started on medication to treat OUD, and it will be key that the care continuum is established prior to discharge from emergency departments [ ].

If there are demonstrable data showing that an intervention during the brief period of an ED visit can be beneficial, the typical lengthy hospital stay for an admission for treatment of IE represents possibly an even more opportune time to engage and work with the patient on their path to OUD treatment. Englander et al. demonstrated that over 50% of individuals who are hospitalized with substance use disorder are interested in being treated for their condition, with 54% (39 out of 72) of individuals with moderate or high-risk opioid use being interested in medication to treat OUD [ ]. It has also been shown that during the course of a hospitalization, a patient will move forward through the stages of change, accepting their illness and becoming ready to begin treatment [ ]. Though patients may not be ready or willing to engage during the initial phase of their hospitalization, evidence suggests that this is a fluid period and patients can change in their willingness to accept treatment. It becomes incumbent on the care team to continue to readdress OUD during the course of the hospitalization and offer treatment if the patient is receptive.

The development of a team approach, when feasible, appears to be associated with the most success. In these settings, it becomes important to engage the patient both from a provider level—a person who can write for the medication to treat OUD at the time of discharge—and wraparound services with either case management or social worker [ , ]. Some programs also enlist peer counselors to assist the patients as they begin OUD treatment, offering a voice from someone who has undergone a similar experience as the patient [ ].

Medications for OUD treatment—all treatment options should be available to inpatients

There are limited options to medically treat OUD but all three medications (buprenorphine, naltrexone, and methadone) need to be available to all patients who have OUD ( Table 8.4 ). Buprenorphine was approved in 2002 for the treatment of patients with OUD and it allows for an office-based approach for this condition [ , ]. The goal of starting buprenorphine while a patient remains in the inpatient setting is that it can allow the individual to be titrated to a dose that allows for the mitigation of symptoms of withdrawal, decrease cravings, and efficient commencement of OUD treatment. It provides the patient an opportunity for immediate engagement in OUD treatment, relieves withdrawal symptoms which often potentiate early hospital elopement, and allows for appropriate linkage to long-term follow-up.