Figure 16.1

Incision options for open distal pancreatectomy. (A) Left subcostal incision. (B) Subcostal extension across the midline. (C) Upward midline extension (“hockey stick”). (D) Lateral extension. (E) (inset), Standard upper-midline incision

16.2.2 Step 2: Isolation of the Splenic Artery and Identification of the Portal Vein

Performing an efficient and safe distal pancreatectomy with limited blood loss depends on early vascular control. First, the left lateral segment of the liver should be retracted superiorly against the diaphragm, using a self-contained retraction system. The central vasculature involved in this operation is initially accessed by dividing the membranous gastrohepatic ligament. Often this ligament is lacy in consistency and is transparent, so that the body of the pancreas is easily recognized through it. Sometimes the duodenohepatic ligament must be divided laterally, somewhat towards the bile duct. Then, inferior traction on the lesser curvature of the stomach will expose the zone of the celiac axis in a deeper plane (Fig. 16.2). A prominent, discoid lymph node (also known as the hepatic artery node or “Node of Importance”) is commonly encountered first. This node can be lifted off the upper border of the neck of the pancreas relatively easily, which exposes the proper hepatic artery and often the takeoff of the gastroduodenal artery (GDA). Unlike in the Whipple procedure, it is not necessary to transect the GDA, which serves as a landmark for the right lateral-most border afforded for pancreatic transection in a DP. Between the proper hepatic artery and the pancreatic neck tissue lies a fairly thin layer of fibrofatty and lymphatic tissue shielding exposure to the anterior surface of the portal vein. Careful transection with cautery exposes the vein beneath and allows for development of the superior aspect of the portal vein “canal,” which defines the neck of the pancreas.

Once these landmarks are secured, dissection can proceed laterally to the left along the upper border of the pancreatic body for a few centimeters. Here, the course of the splenic artery is identified, usually after first dissecting through some fibrofatty tissue. Within a few centimeters of its origin from the celiac axis, the splenic artery usually disappears within the tissue of the pancreatic body. It should also be recognized that its trajectory is more often posterior-to-anterior, arising deep from the retroperitoneum, rather than in a coronal left-to-right plane, as depicted in many texts. Length should be achieved along the splenic artery in preparation for its ultimate transection. A vessel loop or 2-0 silk suture can be loosely placed around it to ensure that inflow control to the pancreas and spleen can be swiftly accomplished should there be inadvertent bleeding later in the procedure. Two tips: First, the left gastric vein (also known as the coronary vein) courses to its insertion into either the portal vein or splenic vein in this zone. Generally, this vein runs posterior (deep) to the splenic artery, but not infrequently it may lie anterior to the artery (as depicted in Fig. 16.2). If so, it will require ligation to access the splenic artery, unless a generous amount of artery is available for ligation lateral to it. Second, dissection of this area may be impractical (if not impossible) exclusively from this window above the stomach, particularly in the obese. If so, better exposure is often achieved by dividing the gastrocolic omentum, as described in the next step. The body of the stomach can then be retracted superiorly to fully expose this region, and manual traction inferiorly upon the pancreatic neck and body “flattens” the dissection plane for better exposure.

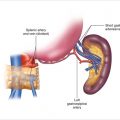

Figure 16.2

Isolation of the splenic artery. After securing the landmarks shown in this figure, dissection laterally to the left along the upper border of the pancreatic body will identify the course of the splenic artery

16.2.3 Step 3: Exposure of the Lesser Sac and Division of the Short Gastric Vascular Arcade

Once inflow control is obtained, full exposure of the pancreatic body and tail can be achieved by dividing the gastrocolic ligament (Fig. 16.3). The easiest area to start is just lateral to the line of the gastric incisura, where there is usually a transparent opening in the adipose tissue beneath the course of the gastroepiploic vascular arcade. Once the free space of the lesser sac is accessed, the omentum can be transected roughly halfway between the vascular arcade and the transverse colon inferiorly. Energy devices such as the LigaSure or Harmonic scalpel are efficient and hemostatic in this layer of thick adipose tissue. Dissection should proceed medially in such a way that the gastroepiploic vascular arcade is followed back to identify its insertion to the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). Then, lateral dissection will proceed superiorly along the greater curvature of the stomach; the individual short gastric vessels are encountered coursing from the stomach to the splenic hilum. If a Warshaw-type, spleen-preserving approach is chosen [8], this step should be withheld, so the spleen can remain vascularized through these vessels. If a traditional DP with splenectomy is performed, meticulous dissection and control of this lienogastric ligament should proceed superiorly to the upper pole of the spleen. Again, while these vessels can be individually ligated with sutures, mechanical coagulation devices, or even vascular staplers, have proven to be highly efficient. Care must be taken, however, to avoid thermal damage to the gastric wall. Next, superior retraction of the stomach against the liver and diaphragm allows for full exposure of the distal pancreas and the pathology of interest.

Figure 16.3

Exposure of the lesser sac and division of the short gastric vascular arcade. During lateral dissection along the greater curvature of the stomach, individual short gastric vessels are encountered coursing from the stomach to the splenic hilum. If splenectomy is planned, dissection and control of the lienogastric ligament should proceed superiorly to the upper pole of the spleen

16.2.4 Step 4: Dropping the Splenic Flexure of the Colon

Exposure of the inferior border of the body and tail of the pancreas, and usually the pathology, requires complete mobilization of the splenic flexure of the colon, which can have variable placement in the left upper quadrant. Particular care should be taken in this dissection to prevent a traction injury, which will tear the splenic capsule and lead to annoying, if not dangerous, bleeding. Fig. 16.4 demonstrates a dissection along two fronts to achieve this objective. First, using electrocautery, the interface of the lateral aspect of the colon should be released along the “white line of Toldt” for a limited distance to allow for medial mobilization. The lower pole of the spleen will be encountered if this dissection is followed superiorly. Next, a lateral dissection of the last elements of the gastrocolic omentum should be completed, connecting to the mobilization achieved by the first dissection. Care should be taken to avoid injuring the colon and to control significant vascular stalks within the lienocolic ligament. Doing so can be particularly challenging in the face of sinistral hypertension from splenic vein occlusion induced by pancreatic pathology.

Once this layer is bisected, a second, deeper plane of transection in fatty tissue is often required so that the colon can be fully mobilized inferiorly. Usually this transection exposes a natural, areolar embryologic plane, but it may be interrupted by the pathology in the tail of the pancreas. At this point, the splenic flexure and more proximal transverse colon can be retracted inferiorly, usually with bulky laparotomy packs behind a deep malleable retractor. This retraction presents a trough inferior to the lower pole of the spleen, allowing some of the posterior and lateral attachments of the lienophrenic ligament to be carefully released.

Figure 16.4

Dropping the splenic flexure of the colon. Dissection is performed along two fronts: (1) The interface of the lateral aspect of the colon is released along the “white line of Toldt” for a limited distance to allow for medial mobilization. (2) Lateral dissection of the last elements of the gastrocolic omentum is completed, connecting to the mobilization achieved in #1. Care should be taken to avoid injuring the colon and to control significant vascular stalks within the lienocolic ligament

16.2.5 Step 5: Dissection of the Pancreatic Body and Exposure of the Superior Mesenteric Vein

Dissection of the pancreatic body commences proximal to the area of pathology and proceeds medially towards the neck. The interface between the pancreas tumor and the base of the transverse mesocolon is released, as shown in Fig. 16.5. This natural embryologic plane is an extension of the lienocolic ligament. Care should be taken to avoid straying within the transverse mesocolon, which can be wafer-thin at times. Continue in this layer directly under the pancreatic neck to expose the anterior surface of the SMV. General landmarks include the termination points of the gastroepiploic and middle colic veins, which often coalesce into a common venous trunk. As depicted in Fig. 16.5, it is common to encounter a small, unnamed venous branch originating directly from the underside of the pancreatic neck and draining into the left side of the SMV. Though delicate (and often frustrating), this vessel must be managed in order to fully expose the portal vein canal and portosplenic confluence from this inferior approach.

Before the next step of dissecting the portal canal, it is useful to obtain control of the pancreatic body. From the dissection plane just created, the pancreatic parenchyma can be fully lifted out of the retroperitoneum in an inferior-to-superior approach along this natural embryologic plane if it is not involved with infiltrative tumor or the effects of pancreatitis. This dissection plane is now posterior to the splenic vein, which at this position is virtually always enveloped within the pancreatic body. Deep (posterior) to this plane is the anterior aspect of Gerota’s fascia. This is the dissection plane that is used to perform a splenorenal (Warren) shunt for relief of portal hypertension. Using manual elevation, the whole body of the pancreas can be encircled within the surgeon’s hand. A window on the superior border of the pancreatic body can be dissected open (lateral to the previously developed splenic artery takeoff, yet above the meandering splenic artery in the retroperitoneum), and a Penrose drain can be placed around the pancreatic body (Fig. 16.6). This will facilitate the ultimate removal of the gland from the retroperitoneum once it is transected proximally. Obviously, pathology situated more proximally in the body of the pancreas may rule out this step at this point.