Older Adults

1 Jefferson School of Nursing, Philadelphia, PA

2 Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, PA

Introduction

Approximately one in eight Americans is over the age of 65. By 2030, 72.1 million Americans will be 85 years or older, representing 19 percent of the population. Women will continue to out number men and by 2030, Hispanics, Asians/Pacific Islanders, Native Americans, and African-Americans are projected to represent approximately 25 percent of the elderly population. Specific nutrition concerns for older adults include eating habits, eating ability, managing meals, relationships, culture, financial resources, and social support. Nutrition-related problems stem from chronic diseases, depression, dementia, dysphagia, obesity, cachexia, and frailty. Nutrition programs will have to become more diverse and flexible to meet the needs of this ever-growing older population. This chapter reviews the impact of aging on nutritional needs and outlines appropriate interventions for many important nutrition-related concerns for the older adult. The following section discusses the concerns of older adults, including fluid and hydration status, health literacy issues, social, cultural, and economic considerations, and physiological and metabolic changes needed to meet nutritional requirements.

Alterations in Nutritional Needs Alterations of nutritional needs of older adults are related to the physiological and metabolic changes associated with aging. Healthy Eating Index Scores among adults 60 years of age and over have demonstrated that only 17 percent had diets that were rated “good”, while 67 percent consumed diets that “needed improvement” and approximately 14 percent reported diets rated “poor”. Caloric needs decline with age due to reductions in resting metabolic rate. Therefore, consumption of nutrient dense foods becomes critically important. A comprehensive nutritional assessment, including past medical history, vital signs, review of systems, physical exam, and biochemical data, is critical to identify those at nutritional risk, as outlined in Chapter 1. Table 5-1 highlights age-related physiological changes and their potential nutrition-related consequences.

Table 5-1 Age-Related Physiologic Changes with Potential Nutrition-Related Outcomes

Source: Nutrition Screening Initiative. 2626 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, Suite 301, Washington, DC 20037. Used with permission.

| Organ System | Change | Potential Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Body composition | ↑ Fat | ↓ Basal metabolic rate |

| ↑ Fat-soluble drug storage, with prolonged half-life | ||

| ↓ Body water | ↑ Concentration of water-soluble drugs | |

| Gastrointestinal | ↓ Gastric acid secretion | ↓ Absorption of folate, protein-bound vitamin B12 |

| ↓ Gastric motility | ↓ Bioavailability of minerals, vitamins, protein | |

| ↓ Lactase activity | Avoidance of milk products, with reduced intake vitamin D and calcium | |

| Hepatic | ↓ Size and blood flow | ↓ Albumin synthesis rate |

| ↓ Activity drug-metabolizing enzymes | Poor or delayed metabolism of certain drugs | |

| Immune | ↓ T-cell function | Energy |

| ↓ Resistance to infection | ||

| Neurologic | Brain atrophy | ↓ Cognitive function |

| Renal | ↓ Glomerular filtration rate | Reduced renal excretion of metabolites, drugs |

| Sensory-perceptual | ↓ Taste buds, papilla on tongue | Altered taste threshold, reduced ability to detect sweet/salt, increased use of salt/sugar |

| ↓ Olfactory nerve endings | Altered smell threshold, reduced palatability causing poor food intake | |

| Skeletal | ↓ Bone density | ↑ Fractures |

Fluid and Hydration Fluid and hydration are especially important to the health of older adults. Older adults often have a poor thirst response and therefore are at increased risk of dehydration or urinary tract infections as are individuals with impaired cognition. Therefore, it is imperative to teach patients to drink fluids on a regular basis. Six to eight glasses of liquids every day will provide sufficient hydration for the healthy older adult; however, it is often difficult to reach this level. Additional drinks such as tea and juices, especially cranberry juice, may be helpful to older adults who need to consume more fluids. However, patients with certain conditions, such as chronic heart failure and kidney disease, may require fluid restriction. In addition, there are potential negative effects of excessive water consumption that can lead to dilutional hyponatremia (water intoxication) and increased nocturia. Due to its sugar content, cranberry juice may not be appropriate for patients with diabetes.

Health Literacy It is important for older adults to understand health information in order to navigate through the health system. To do this, patients need the capacity to process health information and understand the health services that are available. This allows them to make better judgments regarding health care services. Education does not guarantee the ability to read. Age-related cognitive decline and past learning experiences impact literacy and this may determine a patient’s ability to interpret food labels, choose proper nutrients, take medications, and achieve better health outcomes. One way to address low literacy situations is through the use of illustrations to improve patients’ understanding of health information and ensure greater adherence to health regimens. Setting up a medication schedule that is easier to follow will also ensure greater compliance. Research shows that patients with low literacy rates do not use a standardized medication regimen even if they are taking medications up to 7 times/day. Studies also show that low health literacy is significantly associated with higher all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure.

Social and Economic Considerations Economic hardship may limit financial resources for adequate nutrition. Deficits in physical functioning contribute to food insecurity, defined as uncertain ability to acquire nutritionally adequate and safe foods, and/or lack of appropriate nutrition in older adults. Many older adults who eat alone make poor dietary choices and may eat the same foods day after day. Reduced social contact, eating meals alone, and inadequate assistance with shopping and preparing food can impact dietary intake. Total caloric intake may be insufficient to meet dietary needs, placing the individual at increased risk for malnutrition. These risk factors often go unrecognized by healthcare providers, family, and friends. Healthcare providers need to inquire about these issues and refer patients with social and economic challenges to social workers and community agencies prepared to intervene.

Cultural Issues Food habits in older adults are the product of ethnic origin and cultural norms imparted at an early age. Food preferences can vary depending on where an individual grew up (e.g., in a rural or urban setting). Food habits develop over a lifetime of experiences and have a strong influence on nutrient intake. Food can provide a means for communication of love or disapproval in families. For older adults, dietary intake shaped by cultural values may be modified by economic decline, stressors, or chronic illness. Practitioners should consider these unique issues and the challenges they present when assessing an appropriate nutritional intervention.

Macronutrient Needs of Older Adults

Energy Body composition changes with age. Lean body mass declines, body fat mass increases, and a lack of physical activity results in lower energy expenditure, all leading to a reduction in metabolic rate (Table 5-1). Therefore, caloric needs typically decline as people advance in age, unless they remain physically active and maintain their muscle mass and hence, their metabolic rate. While obesity is a major problem in adults, later in life, negative energy balance (caloric malnutrition) may result due to changes in taste, dentition, cognitive impairment, and depression.

Protein The current recommended daily amount (RDA) for protein (0.8 g/kg per day) is the same for adults of all ages, although there is evidence that a higher protein intake could help counteract sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass) in the older adult by enhancing the hypertrophic response to strength conditioning. The oldest age groups are most at risk for protein deficiency especially when health problems or other stresses are manifested and when patients are institutionalized, hospitalized, or reside in long-term care facilities.

Lipids, Carbohydrates, and Fiber There is a decrease in the intake of fat and cholesterol with age. There is also a reduction in the percentage of calories coming from fat. While absolute intake of carbohydrate typically decreases with age, carbohydrate as a percentage of calories increases slightly due to the reduction of calories coming from fats. Most adults, including the elderly, consume less fiber than the recommended of 25 to 35 g/day. Increasing dietary fiber helps prevent or alleviate constipation and may contribute to the prevention of age-related chronic diseases, such as coronary heart disease, and is beneficial for those with diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and gastrointestinal conditions, as described in Chapters 8, 9, and 10.

Vitamin Needs of Older Adults

Vitamin A The RDA for vitamin A is 900 μg/day for men and 700 μg/day for women and requirements do not change with age. The tolerable upper intake level for adults is 3000 μg/day. Concentrations of vitamin A decrease with aging, and lack of dietary or supplemental intake of vitamin A may further exacerbate this deficiency. Often individuals who face economic hardship do not consume sufficient food sources of vitamin A. Retention of vitamin A seems to be enhanced in aging, especially in older adults who consume large amounts from supplements and fortified food. Studies suggest that vitamin A may be helpful in maintaining age-related immune function, and proper vision (Chapter 5: Case 2). Foods sources of vitamin A are listed in Appendix A.

Vitamin D The RDA for vitamin D in men and women 51 years and older is 600 IU/day, and for those over 70, requirements increase to 800 IU/day. In clinical practice, higher doses may be prescribed without apparent undue effects. The tolerable upper intake level for adults is 2000 IU/day. There is an increased need for vitamin D in older adults due to age-related changes, specifically less efficient skin synthesis of vitamin D. In North America, it is estimated that 50 percent of the older population is vitamin D deficient. Vitamin D status can also be negatively impacted by the use of sunscreen, being home-bound, and northern latitude.

The NIH Office of Dietary Supplements defines serum levels of 25(OH)D of 30 to 50 nmol/L as inadequate for overall health. Vitamin D deficiency results not only in impaired bone metabolism, but also muscle weakness, predominantly in the proximal muscles group. Vitamin D supplementation in vitamin D-deficient older adults improved muscle strength, walking distance, and functional ability, and resulted in a reduction in falls and non-vertebral fractures. Studies also show a protective relationship between sufficient vitamin D status and lower risk of colorectal cancer.

Vitamin D status should be routinely assessed and supplements prescribed when food intake is inadequate to maintain optimal health status. Foods sources of vitamin D are listed in Appendix B. It is important to teach patients that sunlight (UVB) exposure from 5 to 15 minutes twice a week helps maintain appropriate levels of vitamin D (in light-skinned individuals). After 15 minutes of sun exposure, sunscreen can be used as a protective measure against skin cancer. This fact should be impressed upon the older adult patient, because the conversion in the skin to the active form of vitamin D from sunlight declines with age. Vitamin D insufficiency has been found to be much more prevalent in darker-skinned populations.

Vitamin E The RDA for vitamin E in adults is 15 mg (22.4 IU) and does not change with age. Alpha tocopherol is the most bioavailable form of vitamin E. Vitamin E absorption and utilization does not change with age, but dietary intake of vitamin E has been shown to be below recommended levels in older adults. A possible explanation is a reduction in high-fat foods containing vitamin E, such as vegetable oils and nuts. For optimal antioxidant function, vitamin E dietary intake needs to be supported with adequate intake of vitamin C, niacin, selenium, and glutathione. However, obtaining vitamin E via supplementation is not recommended. A recent meta-analysis concluded that high doses of supplemental vitamin E, more than 150 IU /day, may be linked with increased all-cause mortality, and supplements exceeding this amount should be avoided. Foods sources of vitamin E are listed in Appendix C.

Vitamin C The RDA for vitamin C is 90 mg/day for men and 75 mg/day for women and requirements do not change with age. The tolerable upper intake level for adults is 2000 mg/day. Intake of vitamin C is highly variable among older adults. While many older adults consume generous amounts of vitamin C and achieve nutritional adequacy, some groups have been identified as having an increased risk of deficiency, especially those with dental problems, dementia, and those in hospitals and nursing homes. Aging does not alter the absorption or metabolism of vitamin C, so low levels are generally attributed to poor intake or increased requirements. The clinical significance of vitamin C deficiency, other than scurvy, has not definitively been established. However, one study found that severe or marginal vitamin C deficiency was significantly associated with all-cause mortality. A meta-analysis of individuals taking vitamin C supplements found that 500 mg daily of vitamin C for a minimum of 4 weeks was associated with a significant decrease in serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglyceride concentrations. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels remained unchanged with vitamin C supplementation. Foods sources of vitamin C are listed in Appendix E.

Thiamin, Riboflavin, and Niacin Thiamin (vitamin B1), riboflavin (vitamin B2), and niacin (vitamin B3) function as coenzymes in energy metabolism. This may lead to the notion that requirements for these vitamins diminish with declining energy requirements in older adults. However, available evidence suggests that requirements for these nutrients are unchanged with age. Potential causes of low blood levels include chronic alcohol use (thiamin) and low consumption of dairy products (riboflavin). Older patients with food insecurity have been reported to have low intake levels of B vitamins.

Folate The RDA for folate in men and women 51 years and older is 400 μg/day. The tolerable upper intake limit for folate has been set at 1000 μg/day. Requirements for folate do not change with age; however, inadequate folate status contributes to hyperhomocysteinemia, which may increase the risk of coronary disease and other chronic diseases common in older adults. Folic acid supplementation has not been shown to reduce the risk of coronary events. A reduction in stroke events was observed in the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation-2 study, but there were no significant effects on death rates and non-fatal myocardial infarction in patients receiving folate supplements. A reduction in the stroke mortality rate was seen in North America after folic acid fortification. Folate intake has increased due to food fortification programs to the point of raising concerns about excessive intake in older adults who consume a large amount of fortified foods such as breakfast cereals, breads, and products made from enriched flours. There is concern that this level of fortification may mask a vitamin B12 deficiency, particularly in elderly individuals, allowing the neurological sequelae to progress even though the anemia associated with this deficiency resolves. Also, high folate levels may reduce the response to anti-folate drugs that are used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, malaria, and some forms of cancer. As a result, higher folic acid intake may not be appropriate for some patients. Foods sources of folate are listed in Appendix F.

Vitamin B12 The RDA for vitamin B12 for men and women 51 years and older is 2.4 μg/day. Requirements for vitamin B12 do not increase with age, but low stomach acid secretion, secondary to atrophic gastritis, may seriously impair the absorption of vitamin B12 in those over age 50. To assure nutritional adequacy, supplements containing vitamin B12 or good food sources of vitamin B12, such as animal and dairy foods, as well as foods supplemented with vitamin B12 (soy milk), should be consumed daily. Widespread use of vitamin B12 injections, once quite popular, is no longer necessary if the free form of B12 is given as an oral supplement at 2000 μg/day. Patients taking metformin and those on acid-suppressant therapy have been shown to have poor vitamin B12 absorption. Serum and red blood cell vitamin B12 levels should be checked and vitamin B12 should be prescribed when levels are borderline or below normal.

Mineral Needs of Older Adults

Calcium The RDA for calcium in men and women 51 years and older is 1200 mg/day. The tolerable upper intake level for calcium is 2000 mg/day. Osteoporosis is a major health risk for older women and men. Calcium recommendations are set at levels associated with maximum retention of body calcium since bones that are calcium rich are known to be less susceptible to fractures. Calcium supplements should be considered for those whose dietary intake of calcium is deficient. More than 70 percent of men and 78 percent of women may have low calcium intake. The disparity between the dietary requirement for calcium and the amount that is actually consumed by the older adult population is the most dramatic of any known essential nutrient, especially in older women. Foods sources of calcium are listed in Appendices G and H.

Iron The RDA for iron is 8 mg/day in both men and women 51 years and older. The tolerable upper intake level for both men and women in this age group is 45 mg/day. Iron is an important component of proteins that transport oxygen, so iron deficiency limits oxygen delivered to the cells. This results in a lack of energy and a decrease in immunity. An excess of iron can cause toxicity and death. Approximately 11 percent of men and 10 percent of women aged 65 and older in the United States are anemic. Rates of anemia rise to 50 to 60 percent in older adults who are living in nursing homes. Poor outcomes from anemia include frailty, increased rates of falls, impaired cognition, and death.

Healthcare providers need to assess iron levels and encourage patients to increase their intake of protein, iron, and vitamin C to provide the nutrients needed for hemoglobin production. When dietary iron intake is inadequate, appropriate iron supplements should be prescribed and an adjunctive stool softener recommended if this causes constipation. Foods sources of iron are listed in Appendix L.

Magnesium The RDA for magnesium is 420 mg/day for men and 320 mg/day for women and requirements do not change with age. The tolerable upper intake level for magnesium supplementation is 350 mg/day, the upper limit for magnesium represents intake from a pharmacological agent only and does not include intake from food and water. Magnesium is an essential nutrient for bone health and functions in conjunction with vitamin D and calcium. It also serves other critical roles such as nerve and muscle function, since it is an integral component to the sodium/potassium pump and required for potassium to enter the cell. Magnesium status has been linked to bone mineral density in both men and women. With age, magnesium absorption decreases, urinary losses increase, and low magnesium intake is often observed. Magnesium supplements have been used to safely treat constipation. Since older adults frequently complain of constipation, magnesium supplementation between 250 to 400 mg per day (taken in the evening) may be beneficial to achieve the recommended intake of magnesium and to relieve constipation. Food sources of magnesium are listed in Appendix K.

Zinc The RDA for zinc is 11 mg/day for men and 8 mg/day for women. The tolerable upper intake level for zinc is 40 mg/day. Aging effects on zinc requirements are not completely understood, but it is likely that zinc needs increase with age. Reduced zinc status in older adults has been linked with decreased immunity and poor response to vaccinations. Zinc supplementation reduces susceptibility to infections and has been shown to enhance wound healing. Studies show that aging is associated with oxidative stress and that zinc is an effective anti-inflammatory as well as an antioxidant. Supplemental doses of zinc should not exceed 40 mg/day unless patients are under regular medical supervision, as high doses can induce copper deficiency and/or immune suppression. Foods sources of zinc include oysters, wheat germ, red meats, liver, dark chocolate, and roasted pumpkin seeds.

Identifying Individuals at Risk for Malnutrition

It is a considerable challenge for practitioners to assist their older adult patients to achieve an optimal balance of nutrients. Older adults who are hospitalized for serious illnesses, nursing home patients, and homebound older adults are at risk for malnutrition. The prevalence of malnutrition increases for those over the age of 70 years and is more likely to occur in individuals living in an urban setting. Overweight and obesity also have pronounced detrimental effects on the health and quality of life of older adults. Evidence is growing that nutritional interventions can improve overall function and quality of life for older adults. Healthcare providers need to appropriately screen, diagnose, and treat malnutrition in older adults in order to minimize the risk for malnutrition and optimize nutritional needs.

Etiology of Malnutrition Decreased oral intake may result from poverty, poor dentition, gastrointestinal pathology, pain, anorexia, dysphagia, depression, social isolation, and pain during chewing or swallowing. Increased nutrient losses can occur secondary to glycosuria, bleeding in the digestive tract, diarrhea, malabsorption, nephrosis, draining fistula, or protein-losing enteropathy. Additionally, any hypermetabolic state (e.g., inflammatory process or cancer) or excessive catabolic process can result in increased nutrient requirements. Surgery, trauma, fever, wound healing, burns, severe infection, malabsorption syndromes, and critical illness can also dramatically increase nutrient requirements.

Nutrition Assessment of Older Adults

The purpose of a brief nutrition assessment is to identify patients at risk for poor or excessive nutritional intake. Nutrition assessment includes the past medical, family, and social history, diet and exercise history, vital signs, review of systems, physical examination, and biochemical data and should be incorporated into routine primary care visits (Chapter 1). The importance of nutritional screening is paramount when caring for older patients because culturally, older adults do not typically express their nutritional concerns. This lack of communication may be related to their loss of independence, fear of dementia, or shame associated with their chronic disease.

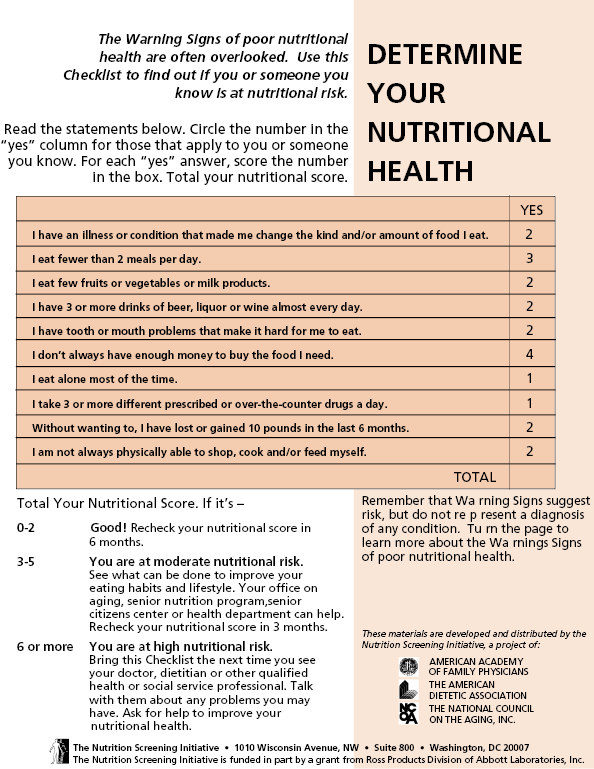

Recognizing individuals at risk for malnutrition is a greater challenge than actually diagnosing the condition once it occurs. Various screening tools have been developed to help clinicians identify patients at risk for malnutrition. The Nutrition Screening Initiative (NSI) can be filled out by the patient and used not only to identify those at risk, but also identify potential contributing factors for malnutrition (Figure 5-1). NSI is a broad, inter-professional effort of the American Academy of Family Physicians, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and a coalition of more than 25 national health, aging, and medical organizations with the goal of promoting the integration of nutrition screening and intervention into the health care for older adults.

Source: Nutrition Screening Initiative Washington, D.C. Nutrition Screening Initiative: Warning Signs.

Functional Status

More than half of older Americans report some degree of disability, and over one-third report severe disability. Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) reflect an individual’s capacity for self-care and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) reflect more complex tasks that enable a person to live independently in the community (Table 5-2). Even after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic status, gender, and ethnicity, level of disability predicts mortality risk in older adults. It is imperative that when taking a medical history of older adults, questions regarding functional capacity be included.

Table 5-2 Commonly Used Measures of Functional Capacity

| Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)* | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs)† |

|---|---|

| Bathing | Telephone use |

| Dressing | Walking |

| Toileting | Shopping: groceries/clothes |

| Transferring | Meal preparation |

| Continence | Housework/laundry |

| Feeding | Home maintenance/repair |

| Take medicines | |

| Manage money |

*ADLs reflect capacity for self-care

†IADLs reflect capacity for independent living

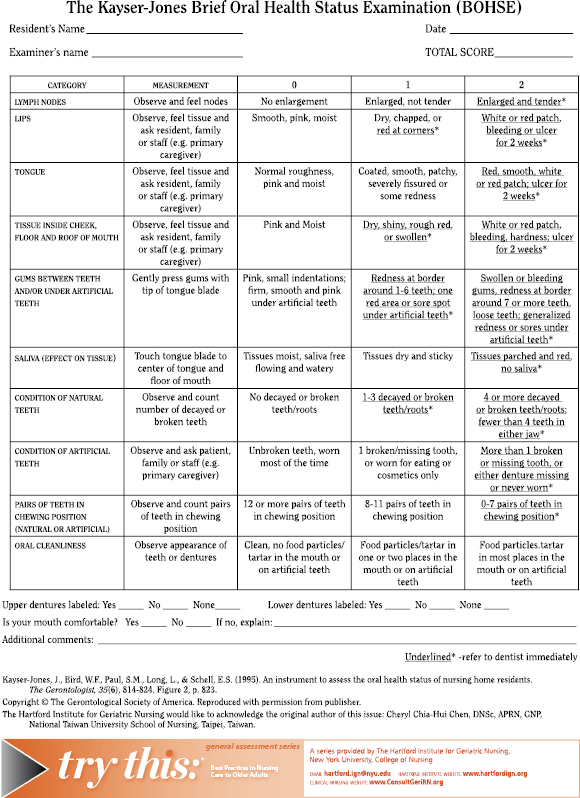

Oral Health Assessment

Oral health assessment is integral to the nutritional status of older adults. Factors that can contribute to oral health problems include tooth decay, ill-fitting dentures, endentulism, pain, disease states, and medications which may alter taste. There is a strong connection between oral health and a person’s general health status. An association has been noted between periodontal disease and myocardial infarction. It has also been reported that endentulous older adults consume fewer servings of fruits and vegetables and more soft foods, often leading to decreased fiber intake. There is a growing need for a community-based coalition of healthcare providers to ensure adequate oral health care for older adults in assisted living facilities, nursing homes, and those visited by home health agency staff. A number of these facilities have on-site dentists and dental hygientists to improve the oral health of their residents. The Kayser-Jones BOHSE oral screening instrument is an appropriate tool to utilize for the oral assessment of older adults (Figure 5-2). Table 5-3 lists soft foods to suggest for patients with chewing difficulty.

Source: The Gerontological Society of America.

Table 5-3 Soft Foods to Suggest for Patients with Chewing Problems

Source: Lisa Hark, PhD, RD, 2014. Used with permission.

|

Physical Examination (also see Chapter 1)

It is important for healthcare providers to begin a physical exam by measuring the height and weight of all patients. This allows calculation of the body mass index (BMI) (weight [kg]/height [m]2), which reflects weight in relationship to height. The association between BMI and mortality follows a U-shaped curve, with increased mortality being associated with BMIs both above and below the ideal range. The nadir of the U-shaped curve increases with age, with the best BMI for older adults ∼25. A BMI of less than 22 kg/m2 indicates that an older patient is underweight and further assessment is warranted. Obtaining a correct BMI may be difficult due to alterations in height caused by kyphosis or the inability to stand for measurement. Patients can therefore be measured in bed in a supine position using a tape measure or lower leg length can be used as a substitute. This possibility makes it important to systematically monitor a patient’s weight over time.

Percent Weight Change Weight loss is common in patients who are hospitalized or who reside in nursing homes. Weight loss is also frequently seen in older adults with significant changes in appetite due to acute illness, chronic disease, or gastrointestinal problems secondary to surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation (Chapters 12 and 13). It is important to take a diet history and determine the percent weight change using the patient’s current weight and usual weight. Malnutrition is diagnosed by clinically significant, unintentional weight loss of 5 percent weight change in a 1-month period or 10 percent weight change over 6 months. This is generally considered a significant weight change that needs further evaluation.

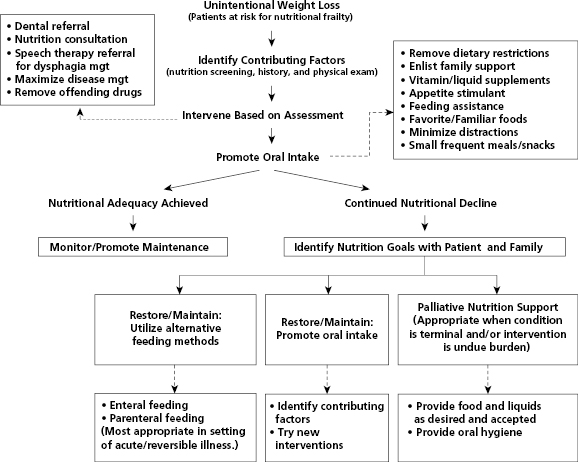

Other Signs and Symptoms Other aspects of the physical exam may reveal many conditions that can contribute to malnutrition, as well as frank malnutrition, for example muscle wasting, in particular temporal muscle wasting (sunken temples), ill-fitting dentures, and mouth sores or abscesses that limit oral intake. It is particularly important to examine patients with cognitive impairment, since they may not be able to verbally report conditions such as constipation, urinary retention, or abdominal discomfort. A brief cognitive screening test, such as the Mini-Mental Status Exam, will help uncover cognitive deficits that may be contributing to poor dietary intake and malnutrition. Figure 5-3 provides an algorithm for assessing, identifying, and treating unintentional weight loss in older adults.

Source: Connie Bales, PhD, RD. 2014. Used with permission.

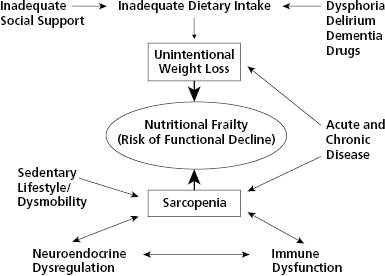

Nutritional Frailty Nutritional frailty is a condition that occurs in older adults and is characterized by low functional reserve, decreased muscle strength, and increased susceptibility to diseases. This is due to sarcopenia (loss of lean muscle mass), which reflects a progressive decrease in anabolism, increased catabolism, and a reduced muscle generation capacity. These changes lead to decreased overall physical functioning, increased frailty, fall risk, and eventually loss of independence. Disease processes, medications, and physical de-conditioning can play a role in the development of nutritional frailty. These factors are elucidated in Figure 5-4.

Source: Connie Bales, PhD, RD. 2014. Used with permission.

Chronic Diseases

Chronic disease is an important risk factor for malnutrition. However, it is important to recognize and address malnutrition as a separate treatable condition from chronic illness. Cancer cachexia has been largely related to the effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines on metabolic processes, causing excessive muscle turnover and wasting syndromes. Reversal of these processes is often difficult, even with adequate nutritional support. Tumor burden, including location and size, can cause symptoms such as dysphagia, early satiety, abdominal pain, and intestinal obstruction that negatively impact nutritional status. Cardiac cachexia is marked by the loss of lean muscle mass and metabolic disturbances that may result from altered cytokine levels.

Weight loss is a common clinical feature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This is likely related to increased resting energy expenditure from the increased work load of breathing and total daily energy expenditure, despite the inactivity associated with the disease process. Similarly, those with cancer, cardiac cachexia, and COPD can have elevated cytokine levels and catabolic processes that lead to muscle wasting. Symptoms such as dyspnea and fatigue may also interfere with caloric intake. Corticosteroids used in the treatment of COPD contribute to reduced muscle mass, reduced bone density, and negative nitrogen balance. Patients with chronic illness may also experience depression. Rates of major depression are particularly high among hospitalized patients with acute illness or those living in nursing homes. Depression often goes unrecognized and untreated, and can affect nutritional status either by an increasing or decreasing appetite.

Cognitive dysfunction is another important cause of unintentional weight loss and malnutrition among older adults. Numerous studies have confirmed the tendency for patients with Alzheimer’s disease to lose weight early in the disease process. Weight loss and subsequent malnutrition can lead to serious consequences, including increased mortality. There are two primary physiologic mechanisms that might explain anorexia and therefore decreased caloric intake in Alzheimer’s disease: taste and smell dysfunction, and the effect of inflammatory mediators (e.g., cytokines) on appetite.

Medications Medication can have a profound impact on nutritional status. Many older adults take multiple medications both prescribed and non-prescribed. Multi-drug regimens are even higher among nursing home residents. Medications can alter nutritional status in a variety of ways, including alteration or loss of taste and smell, nausea, anorexia, dry mouth, diarrhea, reduced feeding ability or increased appetite. Non-prescription and recreational drugs should not be overlooked, since they can contribute to the overall problem.

Dietary Modifications When calorie and protein intake are inadequate, it is appropriate to remove traditional dietary restrictions related to disease processes, a position strongly supported by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. For example, low sodium and low cholesterol diets have a profound negative impact on the taste and smell of food, and limit overall food intake. On a positive note, flavor and caloric enhancement, such as butter, margarine, oil, and powdered milk, have been shown to increase food intake and maintain weight in nursing home residents. Additionally, having someone to eat with has been shown to significantly increase food consumption among homebound older adults. Some facilities offer older adults a glass of wine before dinner to help stimulate their appetite and provide a social event such as “happy hour.” Table 5-4 lists key points to tell older adult patients to improve over intake and appetite.

Table 5-4 Key Points to Improve Appetite

Source: Lisa Hark, PhD, RD, 2014. Used with permission.

Make Eating an Enjoyable Experience

|

Dysphagia Dysphagia can contribute to weight loss among frail older adults. Many neurological conditions effect the enervation of muscles which control swallowing and cause dysphagia. Esophageal muscle dysphagia is more often due to mechanical abnormalities such as strictures, webs, carcinoma, or extrinsic compression. Symptoms of dysphagia usually include coughing, coryza, and aspiration pneumonia. It is important to ask about difficulty swallowing, as well as coughing or watering of the eyes with meals and intolerance to solids or liquids.

For optimal patient care, referral to a speech pathologist for swallowing studies can assist in diagnosing dysphagia, developing a treatment plan, and educating patients and caregivers. In older adults diagnosed with dysphagia, altering food and liquid consistency can minimize the risk of aspiration and reduce weight loss. Techniques to minimize the risk of aspiration include positioning the patient upright during mealtime and for 30 minutes after meals, tucking the chin during swallowing, and swallowing multiple times with each bolus.

Interventions for Malnutrition and Nutritional Frailty

Much of the research and guidelines for assessing and managing frailty in older adults have been done in the context of nursing home patients. In the nursing home environment, it is easier to monitor nutritional status closely and the resources to intervene are at hand, including the availability of dietitians. Many of the interventions applied in nursing homes can be applied in out-patient primary care settings. It is important for clinicians caring for older adults in out-patient settings to be knowledgeable about the potential benefits, risks, and costs of specific interventions.

Supplements for Nutritional Frailty

When adequate nutrition cannot be achieved from ad libitum (self-regulated) meals, commercially prepared (usually liquid) nutritional supplements are often prescribed to increase total nutrient and caloric intake. These products provide a good source of shelf-stable nutrients in appropriate amounts. However, some products may be low in protein and/or fiber content and they may be misused as meal replacements rather than as supplements to a meal. Timing of liquid nutrition supplements can be a major determinant of their effectiveness. These drinks should not be given with meals, but in between meals and/or at bedtime. The chance of electrolyte and carbohydrate overload in chronic renal insufficiency and diabetes should be considered.

A meta-analysis of 55 supplementation trials showed that hospitalized patients (more than 65 years of age) and/or malnourished patients benefited the most and had fewer complications and decreased mortality from using these supplements. In the community setting, liquid protein/calorie supplements may benefit those patients with limitations in their oral food intake, such as food intolerances, and inability, or unwillingness to eat, and the more severely malnourished.

Appetite Stimulants and Antidepressants

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree