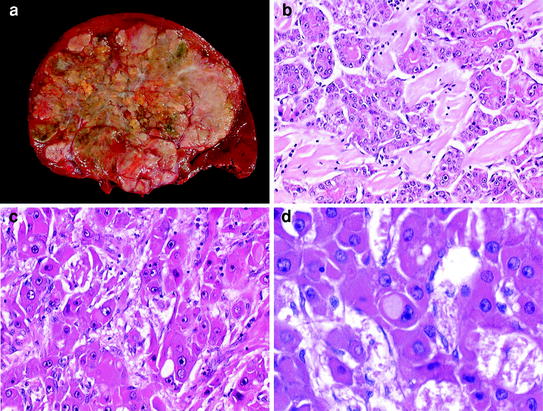

Fig. 1

Macroscopic aspects of Hepatocellular carcinoma: a Nodular pattern of HCC developed in a cirrhotic liver. b Infiltrative pattern of HCC developed in a cirrhotic liver. c Early HCC (progressed type) on a cirrhotic tissue. d Nodular HCC developed in a normal liver in the context of metabolic syndrome

Recently, small HCC, with a maximum diameter of <2 cm, has been subdivided into vaguely and distinctly nodular HCC, two patterns with differences in prognosis with the vaguely nodular form (early HCC) having a better prognosis than the distinctly nodular one (progressed HCC) (the [8, 9]).

2.1.2 Histology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

On histology, the main hallmark of HCC is its resemblance to the normal liver both in its plate-like growth and its cytology [10]. HCC is usually a hypervascularized tumor showing different degrees of hepatocellular differentiation, ranging from well to poorly differentiated, that are based upon the architectural and cytologic features. Different histological patterns may be seen: (1) the trabecular pattern of growth where tumoral hepatocytes are arranged in plates of various thickness, separated by sinusoid vascular spaces, (2) the acinar or pseudoglandular pattern showing gland-like dilatation of the canaliculi between tumor cells (lumens can contain bile) or central degeneration of trabeculae (lumen containing mainly fibrin), and (3) the compact or solid pattern composed of thick trabeculae compressed into a compact mass (Fig. 2).

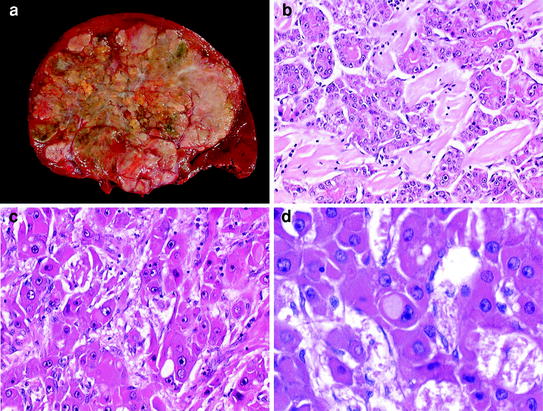

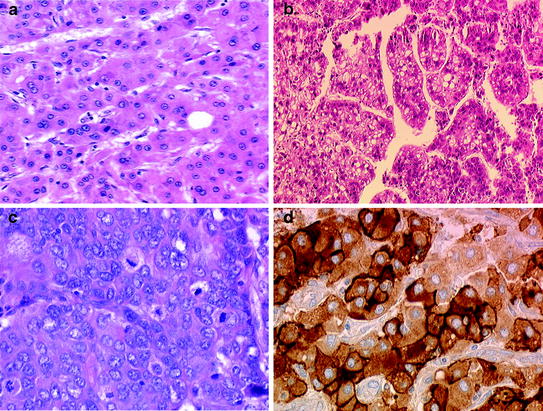

Fig. 2

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a Macroscopic view showing a large well-limited tumor, polychrome with fibrous stroma. b Histologically, tumoral cells are surrounded by hyaline fibrous bands. c Tumor cells are large, eosinophilic with prominent nucleoli. d Pale bodies may be observed in the tumor cells

Cytologically, tumoral hepatocytes are polygonal, displaying an eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, rounded nuclei and prominent nucleoli. The importance of cell pleomorphism varies according to the degree of differentiation. Several variants of HCC are described according to the cytological aspect of the hepatocellular proliferation. The clear cell variant is made of clear cells which may contain fat or glycogen. In the scirrhous HCC, tumor cells are generally smaller in size, showing a granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and conspicuous nucleoli [11]. Sarcomatoid HCC is characterized by a sarcomatous-appearing component of spindle-shaped or giant tumor cells [12]. Sclerosing HCC is a rare variant characterized by abundant, diffusely distributed fibrous stroma and compressed malignant hepatocytes. Such tumor tends to occur in an older age group, affect men and women equally, and might be associated with hypercalcemia [11].

2.1.3 Molecular Tissue Markers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Additional study, such as immunohistochemistry, may be used in routine practice for the diagnosis of HCC. A large variety of immunophenotypical markers of HCC has been described, including highly specific markers (HepPar1, albumin, fibrinogen, α1-anti-trypsin and Alfa-Fetoprotein). In cases of poorly differentiated tumors, such markers display insufficient performance and additional markers are useful. Among them, Glypican-3 (GPC-3), an oncofetal protein, seems to be the more efficient with more than 80 % of HCC immunopositive [13, 14]. Interestingly, immunophenotyping, based on a panel of antibodies, has shown its performance in the differential diagnosis of early HCC and dysplastic nodules [15, 16].

Furthermore, genomic studies provided molecular classifications of HCC based on gene expression [17, 18]. Such analysis allowed the identification of subgroups of patients according to etiological factors, stage of the disease, recurrence and survival [19, 20, 21]. Major classes of tumors emerging from these comprehensive analyses are also related to important carcinogenesis pathways such as activation of ß-catenin, AKT/mTOR, or inactivation of TP53 and RB1 [22, 21].

2.2 Grading and Pathological Prognostic Factors

Grading of HCC has relied for many years on Edmondson and Steiner system, which divided HCC into four grades from I to IV on the basis of histological differentiation [23]. Grade I is the best differentiated consisting of small tumor cells arranged in thin trabeculae. Cells in grade II are larger with abnormal nuclei and glandular structures may be present. In grade III nuclei are larger and more hyperchromatic than grade II cells and cytoplasm is granular and acidophilic, but less than grade II. In grade IV, tumor cells are much less differentiated with hyperchromatic nuclei and loss of trabecular pattern. In fact, most of HCC present as grade II or III. Importantly, grading heterogeneity inside a tumor is frequently observed and may significantly limit performance of biopsy for grading, especially when using a four-tier grade scaling [24]. Therefore, and compared to other carcinomas, there is a tendency to simplify the grading and use a three-scale system including well-, moderately and poorly differentiated HCC. Finally, tumor grade appears as a weak independent predictor of the clinical course, providing little prognostic information [25, 26]. The main prognostic factors of HCC are related to tumor stage (number and size of nodules, presence of vascular invasion and extrahepatic spread), liver function (defined by Child–Pugh’s class, bilirubin, albumin, portal hypertension) and general health status. Among them, size is a major prognostic factor, with a very good prognosis for small or minute carcinomas. The presence of vascular invasion and satellite nodules around the main tumor has also been recognized as predictor of recurrence and survival in several studies [27, 28].

Using microarray technology, recent studies have shown that a subset of adult HCC displays phenotypical traits of progenitor cells. These tumors retain stem cell markers and express Cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK19. Interestingly, worse survival was demonstrated for this subgroup ([29], Gut).

2.3 Preneoplastic Lesions and Early HCC

2.3.1 Dysplastic Nodules

It is commonly accepted that in the context of cirrhosis, there is a stepwise progression from cirrhotic nodule to HCC. A unified nomenclature of such liver nodules has been recently reviewed [8]. According to such classification, one distinguished benign macroregenerative nodules that are histologically indistinguishable from the adjacent parenchymal cirrhotic nodules and dysplastic nodules (DN) that differ from the surrounding liver parenchyma with regard to size, color, texture and degree of bulging of the cut surface. DN are further subdivided into low (LGDN) and high grade (HGDN), the latter being closer to HCC in the spectrum of hepatocarcinogenesis. The premalignant nature of DN is supported by different clues including the common association with HCC in cirrhotic livers, the presence of cyto-architectural abnormalities and morphologic evidence of neoangiogenesis, the detection of both genetic and epigenetic changes close to overt HCC [30, 31, 32, 33]. LGDN display features suggestive of a clonal cell population without significant architectural atypia while HGDN show cytological and architectural atypias (including enlarged, crowded, or irregular nuclei, irregular thickening of hepatic plates with focal loss of reticulin framework) but insufficient for a diagnosis of malignancy.

2.3.2 Small Hepatocellular Carcinoma

According to the international consensus on small nodular lesions in cirrhotic liver, small HCC are subdivided into two different entities: early (vaguely nodular type) and progressed HCC (distinctively nodular type) [8]. Although less than 2 cm, both types may display significant morphological changes with different vascular dynamic profiles on imaging. The progressed form is usually a moderately differentiated HCC able to invade the vessels and to metastasize. Early HCC are rather considered as “in situ carcinoma” showing well-differentiated proliferation [34, 35]. Differential diagnosis of early HCC and HGDN relies on a set of morphological features. Among them, stromal invasion, defined as the presence of tumor cells invading into the portal tracts or fibrous septa, has been proposed as the most relevant feature discerning HGDN from early HCC [8]. Such feature, initially reported in the Japanese series, may be difficult to identify, especially on biopsy specimens. In that context, surrogate immunomarkers, including a three antibodies panel (GPC-3, Glutamine synthetase, and HSP70), have been shown to be helpful in the differential diagnosis of HGDN and early HCC as well as in the recognition of stromal invasion in early HCC using CK 7 immunostaining [15, 36].

2.3.3 Dysplastic Foci

Dysplastic foci are defined as microscopic changes incidentally recognized in cirrhotic tissue. They are recognized, based on cytologic criteria, into large or small liver cell changes previously reported as large/small liver cell dysplasia. While large liver cell change consists of abnormal but non-neoplastic hepatocytes that is predictor of HCC development, small liver cell change is composed of neoplastic cells that are direct precursor of HCC [37, 38].

3 Hepatocellular Carcinoma Without Cirrhosis

Although the large majority of HCC arise in patients with advanced chronic liver diseases, HCC may be observed without advanced liver fibrosis or even in underlying normal liver. Altogether, such HCC appear to have a better prognosis, mainly related to the absence of advanced damages in the background liver.

3.1 Hepatocellular Carcinoma Associated with Chronic Liver Diseases

HCC may occur early in the process of chronic liver diseases before the stage of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. Although this situation may be observed whatever the etiological cause, it is especially encountered in the context of hepatitis B viral infection and metabolic syndrome (MS) [39, 40, 41]. Due to the increase in the prevalence of MS worldwide, HCC associated with MS will become a major concern. Fatty liver diseases, which represent the liver manifestation of MS, encompass a large spectrum of liver changes, from simple steatosis to steato-hepatitis that may progress to fibrosis [42, 43, 44]. Although, and as in other chronic liver diseases, the presence of cirrhosis may promote per se development of HCC in such patients, diabetes and obesity, as factors of MS, also appear to be independent risk factors in liver carcinogenesis [45, 46]. Interestingly, several studies reported significant number of cases of HCC in patients with non-advanced liver fibrosis [47–49, 41]. These data support the hypothesis that liver carcinogenesis related to MS may follow distinct molecular pathways of tumorigenesis, independently from the usual multistep process-fibrosis-cirrhosis-HCC at least in some cases. A small subset of these HCC, mainly occurring in male patients, develops from the malignant transformation of preexisting hepatocellular adenoma [50]. Morphologically, these HCC present as larger and better differentiated tumors compared to those diagnosed in a background of cirrhosis.

3.2 Hepatocellular Carcinoma on Normal Liver

In fact, very few HCC are observed in patients with strictly normal liver. They correspond to distinct variants of tumors, occurring either in specific population or specific context. Such situation may partly explain their better prognosis compared to HCC arising in patients with advanced chronic liver diseases.

3.2.1 Fibrolamellar Type of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Fibrolamellar HCC, first described by Edmondson in 1980, is a rare entity, accounting for less than 1 % of all cases of primary liver cancer [51]. Fibrolamellar HCC is mostly encountered in young population without chronic liver disease, or other known predisposing risk factors [52]. On gross examination, fibrolamellar HCC is firm, mostly well-defined single nodule ranging from 5 cm to over 20 cm. On cut section, prominent fibrous septa subdivide the mass and may connect with a central zone of scarring and calcifications may be observed. Histologically, the key-features include the presence of lamellar stromal bands surrounding nests of large polygonal eosinophilic tumor cells with prominent nucleoli. Cytoplasmic inclusions of various types are common, including ground-glass pale bodies, eosinophilic cytoplasmic globules of variable PAS-positivity, and rarely, Mallory bodies. In contrast to most HCC, fibrolamellar HCC seems to express abundantly type CK 7 and, in some cells, biliary-type CK 19 [53]. Despite its large size at time of diagnosis, prognosis of fibrolamellar HCC is usually considered better than conventional HCC, especially due to the good shape clinical condition of the patient without chronic liver disease. Fibrolamellar HCC tends to be slow-growing and frequently surgically resectable with a better prognosis than other types. However, when adjustment is made for tumor stage, all series do not demonstrate this better prognosis. Successfully resected patients have good chance of long-term survival despite occurrence of extrahepatic recurrences (Fig. 3).

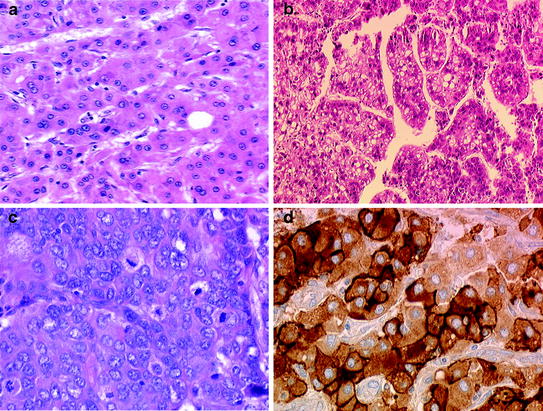

Fig. 3

Histologic features of Hepatocellular carcinoma: a Well-differentiated HCC with trabecular architecture, few pseudoglandular structures are present. b HCC showing steatotic tumor cells. c Poorly differentiated HCC with increased mitotic figures. d Glypican-3 immunostaining showing cytoplasmic positivity in most of tumor cells

3.2.2 Malignant Transformation of Hepatocellular Adenomas

Hepatocellular adenomas (HCA) are rare benign neoplasms of the liver, mainly observed in young women, strongly associated with oral contraceptive use [54]. This tumor can also occur in men receiving anabolic steroids [55] or be associated with underlying metabolic diseases, such as glycogenosis and more recently MS [56, 57]. Malignant transformation into HCC is one of the most important complications of HCA, reported between 4 and 10 % in the literature [58, 59, 56]. Several risk factors for malignant transformation are now recognized, including the gender (increased in male patients), the size (>5 cm), and the subtype of HCA (especially those displaying β-catenin activation) [58, 50]. Importantly, the number of HCA does not impact their malignant potential. Malignancy commonly displays well-differentiated HCC inside the HCA, with exceptional vascular invasion or satellite nodules [50].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree