BACKGROUND

Obstetric intervention in pregnant women with pregestational diabetes prior to spontaneous labor has been standard practice for decades. The objectives were, and still are, to avoid the fetus dying in utero and to avoid the hazards of obstructed labor or shoulder dystocia associated with fetal macrosomia. In an effort to achieve these goals, cesarean section rates for women with pregestational diabetes in most parts of the world are more than 50%. Iatrogenic prematurity has resulted in high rates of admission to neonatal intensive care in Type 1 diabetes. While it may be the objective of the health professional to obtain a normal outcome (spontaneous labor, normal delivery, and no neonatal care admission) in women with pregestational diabetes, this is achieved in only a minority of cases. By contrast, such a goal should be achievable in the majority of women with gestational diabetes not requiring insulin. Although there are general guidelines to follow, an individualized approach to the timing and mode of delivery is essential. This is particularly so in Type 1 diabetes where many factors need consideration, including glycemic control, diabetes complications, past obstetric history, fetal growth, and the availability of healthcare resources in labor. The management of labor should follow standard practice as for the woman without diabetes. Particular attention is needed with regard to fetal monitoring and signs of delay in labor.

TIMING OF DELIVERY

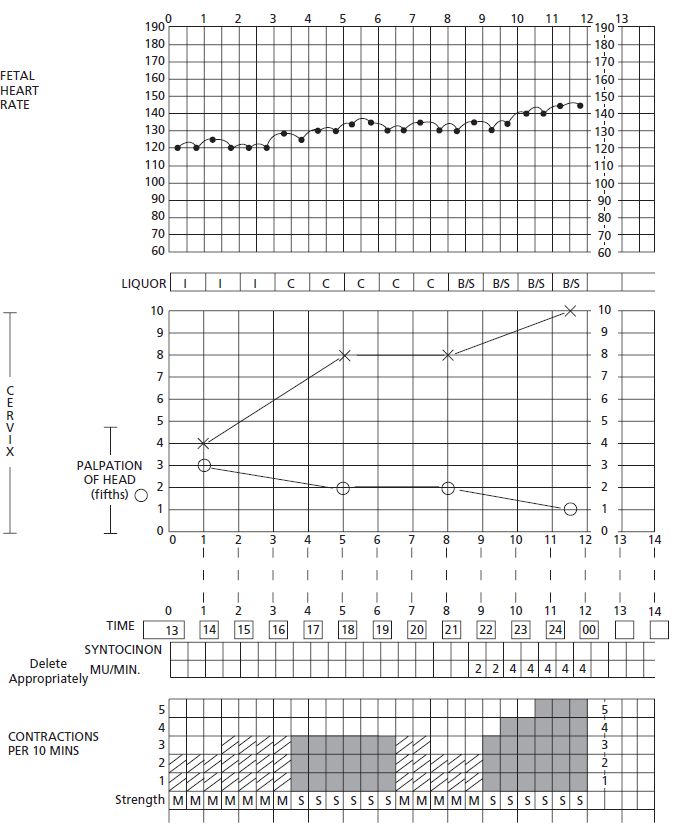

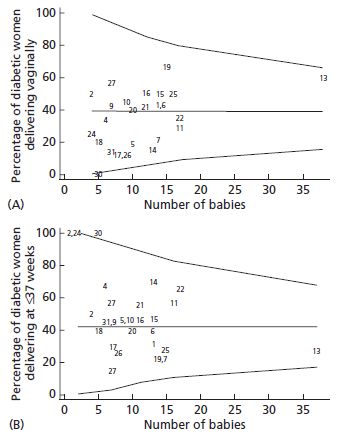

The decision of when during pregnancy to deliver a woman who has diabetes reflects the obstetrician’ s opinion of the gestational age at which the risk of possible excessive fetal growth, plus the risk of unexpected fetal demise, is balanced by the risks of induction of labor and/ or cesarean section. Data from the 2002-2003 UK survey1 showed that 35.8% of women with pregestational diabetes delivered at under 37 weeks of gestation compared to 7.4% in the general population. While an increased incidence of spontaneous preterm birth compared to the general population was anticipated from previous studies, 26.4% of the total births were delivered iatrogenically preterm. Wide variation in practice exists within the UK, suggesting that the attitude of health professionals plays a major role in determining the timing and route of delivery for diabetic women. A method of demonstrating the significance of this variation across a region in the UK using a funnel plot has been described (Fig. 20.1A).2

Fig. 20.1 Funnel plot showing variations in (A) vaginal delivery rates and (B) preterm delivery rates in women with established pregestational diabetes across 25 units in the North West of England. The 99% confidence intervals are marked. Some of the smaller units lie outside these limits.2 The numbers within the plots are the codes for the individual units.

Large studies are needed to address the risks and benefits of delivery prior to 40 weeks. The few relevant studies have either been composed entirely or predominantly of women with gestational diabetes. A US study3 randomized 187 women with insulin-requiring gestational diabetes and 13 with pregestational diabetes to either intervention at 38 weeks or expectant management. As anticipated, intervention was associated with a lower rate of babies weighing at or above the 90th centile for gestational age (10% vs 23%; p = 0.02) and a trend towards a reduction in shoulder dystocia (0% vs 3%; not significant). Similarly, a case-controlled study in insulin-requiring gestational diabetes from Israel (n = 260)4 showed a reduced prevalence of shoulder dystocia in women delivering at 38-39 weeks compared to those delivering at or beyond 40 weeks (1.4% vs 10.2%; p < 0.05). Neither study showed an increase in cesarean section rate with induction of labor prior to term. While it might be expected that induction by 38-39 weeks will reduce the risk of stillbirth or early neonatal death of normally formed babies, there is no evidence as yet to support this.

Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes

The current UK guidelines advise that diabetic women should be offered elective delivery after 38 completed weeks,5 assuming no other significant factors have developed before this time. Current US guidelines recommend that if diabetes is well -controlled, the pregnancy may be allowed to go to, but not beyond, term.6 In practice, the clinician is often faced with a decision as to whether or not to deliver even earlier and there may also be contraindications to such intervention. In making a decision about the timing of delivery, it is necessary to individualize care, taking into account a number of maternal and fetal factors, including:

- Poor maternal glycemic control-as episodes of maternal hyperglycemia may cause fetal acidemia, the fetus may be at risk of unexpected death in utero

- Progression of maternal diabetic complications maternal renal impairment, hypertension, neuropathy or retinopathy may all cause significant concerns about maternal health (see chapters 15-17)

- Fetal macrosomia-as assessed by serial ultrasound (see chapter 12)

- Fetal growth restriction or compromise-as assessed by ultrasound and other methods of fetal surveillance (see chapter 12)

- Maternal preference, particularly if there is a poor obstetric history.

Neonatal facilities should not influence the decision, as if premature delivery is indicated and facilities are not available locally, then in-utero maternal transfer to a maternity unit with these facilities should occur.

In the UK 2002-2003 survey1 of pregestational diabetes, there was a 39% induction rate (general population rate 21%). The main reasons stated for induction were routine (48%), general obstetric complications (14%), presumed fetal compromise (9%), anticipated large baby or polyhydramnios (9%), and diabetes complications (2%).

Gestational diabetes

Women with gestational diabetes range from those with undiagnosed Type 2 diabetes to those with mild impairment of glucose tolerance diagnosed for the first time during pregnancy which is corrected following appropriate dietary measures. Again care should be individualized at least to a degree. The studies mentioned above3,4 relate primarily to insulin-requiring gestational diabetic women and accordingly there is a case for considering elective intervention in these women at 38–39 weeks, particularly if macrosomia is suspected, as these studies showed a reduced incidence of shoulder dystocia in the intervention groups. In addition, other maternal or fetal factors may indicate the need for either early or delayed intervention. However, for women who have been managed satisfactorily with diet alone and who have no specific other risk factors (e.g. macrosomia), treatment should be similar to the general obstetric population.

MODE OF DELIVERY

Incidence of cesarean section and vaginal delivery

Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes

Studies show an increased incidence of delivery by cesarean section compared to the general population. The figure from the UK survey of 3474 women in 2002–2003 was 67% compared to the overall population rate of 24%.1 Although the data were not presented by type of diabetes, the rate tends to be lower in women with Type 2 diabetes, as these women are often older and multiparous, and may well have had their previous pregnancies at a time when they had normal or only impaired glucose tolerance. This wide variation in rates is illustrated by a funnel plot for the North West of England (Fig 20.1B).

Gestational diabetes

In gestational diabetes cesarean section rates tend to be higher than those of the background population. However, studies have shown that this may be attributable to other factors, such as maternal obesity, which is independently associated with fetal macrosomia7 and probably to traditional obstetric practice.8,9 The multiethnic international Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study has provided additional data as women with abnormal glucose tolerance during pregnancy short of diabetes (defined by a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT] at approximately 28 weeks of gestation) were managed with the caregiver and participant being blinded to the OGTT result.10 Although the strength of the positive association between maternal glucose concentrations and primary cesarean section rate was attenuated after controlling for confounding variables, there still remained a significant relationship between hyperglycemia during pregnancy and cesarean section rates. In addition, labeling a woman with gestational diabetes may result in clinicians favoring cesarean delivery, thus negating any possible treatment-induced reduction of macrosomia being translated into a greater likelihood of vaginal delivery. In the randomized controlled Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study (ACHOIS) trial there was no difference in the cesarean rates between treated and untreated gestational diabetes groups despite the latter group having been double-blinded.8 In the Canadian Tr i-Cities case – control study, the cesarean delivery rate for women with treated gestational diabetes was 33.6% compared with 29.6% for those who were untreated, despite the treated group having reduced macrosomia.9 The cesarean rate for controls was 20.2%, but multivariate analysis showed that compared to the untreated group, it was not the gestational diabetes which increased the risk.

Indications for cesarean or attempted vaginal delivery

The indications for cesarean section are often multiple, making analyses of the reasons difficult. However, apart from general obstetric complications, a number of factors can be considered individually:

Previous cesarean section

Existing data, mainly from studies in gestational diabetes, do not suggest that women with diabetes should be treated differently from those without diabetes and accordingly should be considered for vaginal birth after cesarean (VABC). None of the studies is able to address the issue of whether there is an increased risk of scar dehiscence in diabetes. One study reviewed only women with diet-controlled gestational diabetes.11 Other studies suffer from problems with the control groups.12,13 However, the Washington State study13 included women with both pregestational and gestational diabetes and showed that fewer women with diabetes attempted VBAC (non-diabetic 64.4%; gestational 58.1%; established 51.0%) and that their success rates were significantly lower (non-diabetic 62.0%, gestational 45.8%, established 36%). These results might be anticipated as any delay in progress in labor in a diabetic woman should raise concern as to the possibility of impending dystocia and the potential for scar rupture.

Routine practice

In some hospitals cesarean delivery in women with pregestational diabetes is almost the routine (Fig. 20.1A). If maternity units have anxieties about caring for diabetic women in labor, women should be offered the choice of transfer to a unit with more experience in the management of pregnant women who have diabetes. This raises the controversial issue as to whether care for such pregnancies should be centralized into a smaller number of larger centers staffed with personnel experienced in the management of diabetes in pregnancy. There are outcome data which tend to support the latter practice.14,15

Maternal diabetic complications

Some express the opinion that from a maternal health perspective a cesarean is safest for the mother whose diabetes is complicated by, for example, hypertension or severe retinal disease. There are no data on this and in the UK survey this was considered the primary indication in only 3%.1 However, in women with vascular complications, there may be associated fetal growth restriction and a cesarean may be indicated for fetal reasons.

Concern about fetal condition

Antenatal fetal surveillance (see chapter 12) may suggest that a fetus is less likely to cope with the hypoxic stresses of labor. The 2008 UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines5 concluded from a review of the evidence that the risk of stillbirth was a determining factor in the decision to perform a cesarean delivery, and this was the primary indication in 28% of cases in the 2002 – 2003 UK survey.1 The survey showed that intrapartum stillbirths accounted for 10% of all stillbirths. The neonatal death rate for the infants of diabetic women was 9.3 per 1000, which was 2.6 times (95% CI 1.7 – 3.9) that of the general population.1

Excessive fetal weight

This was the other major factor considered in the UK NICE guidelines,5 but in the 2002 – 2003 UK survey,1 this was recorded as the primary indication for cesarean in only 4%. However, in 14% of women the indication for section was delay in progress in labor. In many of these women, the concern may have been about excessive fetal weight, with the possible sequelae of perinatal death or morbidity (see below). The UK survey showed that the birthweight distribution of the stillbirths was similar to that of the live births.16

Maternal stature, ethnic group, and corrected birth-weight centiles may also assist decision-making. In the multiparous woman with a suspected large fetus, other relevant factors include the previous successful vaginal delivery of a baby of similar weight to that estimated for the current pregnancy or a comparison of antenatal ultrasound serial biometry of a previous fetus with those of the current pregnancy.

Shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury

The possibility of shoulder dystocia and subsequent brachial plexus injury undoubtedly influence the clinician’ s decision as to how best to deliver the baby of the diabetic mother. It is always uppermost in the mind of clinicians looking after a woman with diabetes in labor. In view of this, there has been much analysis of the role of cesarean delivery in this regard.

The current UK rate of shoulder dystocia in women with pregestational diabetes is 7.9%.1 A large US regional study reported population rates of 3%,17 while a large study from Boston, US revealed an incidence of 1.2%.18 Brachial plexus injury was reported in 4.5 per 1000 UK births to mothers with pregestational diabetes,1 which was estimated to be 10 times greater than the general population rate of 0.42 per 1000.19 The difference between rates in women with or without diabetes is less marked in the Boston study, but the diabetic group included women with gestational diabetes.18 In the UK study of pregestational diabetes, 25% of the babies with brachial plexus injury were delivered by cesarean section.1 The mechanism for the injury in the latter cases is unclear, but excessive head traction may still be applied at cesarean delivery. Similarly, only two-thirds of the vaginal deliveries with brachial plexus injury were described as having been complicated by shoulder dystocia,1 similar to that reported in the general population. 17–19

Pregestational maternal diabetes and infant birth-weight appear to be independent risk factors for brachial plexus injury16 with an odds ratio of 9.6 (95% CI 6.2–14.9) for infants weighing more than 4000 g compared to those weighing less. The odds ratio increased to 17.9 (95% CI 10.3 – 31.3) for birthweights above 4500 g and to 45.2 (95% CI 15.8 – 128.8) above a birthweight of 5000 g. In the HAPO study, the prevalence of shoulder dystocia was 1.2% (n = 311), but rates varied from 0.1% to 3.4% among centers.10 In the latter study, there was a significant relationship between worsening glucose tolerance and shoulder dystocia even after controlling for confounding variables. However, in clinical practice, birth-weight predictions may not be that helpful as typically 40 – 60% of cases of shoulder dystocia occur in babies weighing less than 4000 g.20 For brachial plexus injury, similar percentages of cases have been reported to occur in babies weighing less than 4000 g, both in non-diabetic and diabetic (gestational and pregestational) women.18

Although there are limitations in the use of fetal weight estimated by ultrasound (chapter 12), in a study of women predominantly with gestational diabetes, it was used at 37 – 38 weeks of gestation to aid delivery decision-making.21 Elective cesarean section was performed when the ultrasound fetal weight estimation was more than 4250 g and labor induced when the weight estimation was on or greater than the 90th centile but less than 4250 g. Compared to the period before weight estimations were performed, there was a significant reduction in the incidence of shoulder dystocia from 2.4% to 1.1% (OR 2.2). The rate of shoulder dystocia in the macrosomic group (defined as ≥ 4000 g) delivered vaginally was 7.4%, but there was a significant 15% rise in the rate of cesarean section from 21.7% prior to the introduction of weight estimations to 25.1% thereafter. Analysis of available data has suggested that using a predicted weight threshold of 4500 g, an additional 443 cesarean sections would be required to prevent one permanent brachial plexus injury.22 Apart from the economic aspects, the benefit of reducing shoulder dystocia must be carefully weighed against the short-and long-term morbidities of cesarean section, not least of which is hysterectomy. In the UK the risk of having a hysterectomy at the time of cesarean is 1 in 220 for a woman who has previously had two or more cesareans.23

PRETERM LABOR AND DELIVERY

The prevalence of delivery before 34 weeks among women in the UK with pregestational diabetes was 9.4% (328 of 3474) and before 37 weeks was 35.8%.1 While the spontaneous preterm delivery rate was 9.4% (general obstetric population 4.7%), of all the preterm deliveries 73% were iatrogenic. Great variation in the incidence of preterm delivery may be seen when comparing different hospitals, which undoubtedly is a reflection of individual hospital policy (Fig. 20.1A).2 A detailed Danish prospective study of pregnancies complicated by Type 1 diabetes attempted to analyse the causes of preterm delivery.24 Having excluded women with significant hypertensive or renal problems, 16 (23%) women were found to have delivered before 36 weeks, mostly for obstetric reasons such as spontaneous labor with or without preceding ruptured membranes or bleeding. The strongest predictor of preterm delivery was a higher hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) concentration throughout pregnancy compared with the women who went to term. This coupled with a mean birthweight of 3.02 kg at a mean gestation of 32.6 weeks is in accord with suboptimal diabetic control, macrosomia, and probably polyhydramnios being associated with spontaneous preterm delivery.

Predicting whether a woman who presents prematurely with contractions is actually going to deliver is often difficult. For the women without diabetes, there is rarely a contraindication to administering steroids to aid fetal lung maturity. However, in the diabetic woman, such therapy must be given with caution as it can precipitate diabetic ketoacidosis. Frequent monitoring of blood glucose and additional insulin are required (see chapter 21), and this applies also to the women with gestational diabetes. Tocolysis may be used, particularly to delay delivery and thus allow the effects of steroids to be beneficial. However, if tocolytics are used, beta-sympathomimetics are best avoided as they are likely to further worsen diabetic control. Other drugs such as calcium channel antagonists (e.g. nifedipine) or magnesium sulfate are preferable as they do not interfere with diabetic control.

If preterm labor supervenes, then management should be as for the non-diabetic woman with premature labor. There is no specific indication for a cesarean section. Continuous electronic monitoring should be utilized once labor is established. Shoulder dystocia may still occur preterm (e.g. 35 – 36 weeks) as a macrosomic fetus could weigh 4 kg at this gestation, and accordingly careful attention should be made with regard to progress in established labor (see below).

PLANNED CESAREAN DELIVERY – PRACTICAL ISSUES

As always prior to elective intervention, the accuracy of the expected date of delivery must be checked. If ultra-sound biometry from the first trimester or at least before 24 weeks is not available, then this is one of the few indications for consideration of amniocentesis to ascertain fetal lung maturity (see chapter 12).

It should be feasible to manage women with diabetes in exactly the same way as women without diabetes other than with regard to their insulin regime (see chapter 21). As many of these women will be obese or have other diabetic complications, a preoperative anesthetic review is advised. Regional anesthesia is preferred to general anaesthesia, as with non-diabetic women. Additional reasons for favoring regional anesthesia include the possibility of hypoglycemia developing whilst under general anesthesia and the risk of aspiration of stomach contents, as the diabetic woman may have decreased gastric emptying associated with a degree of autonomic neuropathy. Possible hemodynamic effects and hypotension, which may be associated with regional anesthesia, should not cause significant problems.

Difficulty with delivery of the shoulders is sometimes experienced and excessive head traction may be avoided by extracting the shoulders digitally; excessive head traction is likely to be the cause of some cases of brachial plexus injury following cesarean.

Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended for planned as well as emergency cesarean sections in view of increased infection risk. Thromboprophylaxis, even in the absence of other risk factors, is also advisable in all cases. The issue of tubal ligation should be raised beforehand with all women having their second or subsequent baby. Postoperative care should be as for any woman after a cesarean apart from with regard to her diabetes treatment (see chapter 21).

INDUCTION OF LABOR –PRACTICAL ISSUES

In view of the general recommendation to consider elective delivery by 38 – 39 weeks in women with pregestational and insulin-requiring gestational diabetes (see above), induction of labor is widely utilized. Prostaglandins are normally required first to ripen the cervix and initiate labor, and this can then be followed by artificial membrane rupture when the cervix is beginning to dilate. Usually oxytocin is required as well and is considered further below. Management should be conducted as for women without diabetes, apart from a few specific points. Induction should take place on the delivery suite or in an alternative well-staffed environment where careful monitoring of fetal condition can be performed using cardiotocography (CTG) and there can be regular monitoring of maternal blood glucose. During the initial phase with prostaglandins, if the woman is not in significant pain and labor has not commenced, she should be permitted to continue to eat and receive short-or ultrashort-acting insulin to cover this, coupled with routine pre-and post-prandial glucose measurements. When labor is established, it is customary to monitor capillary blood glucose hourly; insulin regimes are discussed in chapter 21. She should also be reviewed by an anaesthesiologist (anesthetist), as there remains a relatively high risk of a cesarean being required in labor. In the UK 2002 – 2003 survey, of the 1975 women with pregestational diabetes who went into spontaneous labor or were induced, 43% had a cesarean.1

SPECIFIC OBSTETRIC ISSUES IN THE FIRST STAGE OF LABOR

Progress in labor and use of oxytocin

The major concern is that of unexpected disproportion between fetus and mother, and possible traumatic delivery. Careful monitoring of progress in labor is required, which may be facilitated by the use of a partograph or Friedman curve. While difficulties with delivery may occur after a relatively rapid first stage of labor, slow progress in the active phase of labor (i.e. ≥ 5 cm cervical dilation) requires careful review by an experienced obstetrician. In the woman having her first labor, stimulation of the uterus with oxytocin may be considered if the contractions have never been very frequent or strong. However, after good progress in labor followed by cessation of cervical dilatation, oxytocin must be used with caution. Intrauterine pressure catheters, whilst not widely used, may be helpful in this situation by quantifying the uterine response to oxytocin. In the woman who has had a previous vaginal delivery, delay in the active phase of labor is normally an indication for cesarean delivery and oxytocin is almost always contraindicated (Fig. 20.2).

Total length of labor

As labor is often induced it may be of considerable duration. There is no need to impose arbitrary time limits as long as progress is being made and both fetal and maternal condition is satisfactory. With regard to the mother, it should be feasible to maintain normal glycemic and metabolic control by careful attention to intravenous fluid regimes despite a prolonged labor (see chapter 21).

Monitoring fetal condition in labor

The fetus of the diabetic mother is probably at higher risk of developing intrapartum asphyxia than the fetus of the woman without diabetes, hence the recommendation for continuous electronic fetal monitoring in labor.25 This increased risk may at least in part relate to the direct association between maternal hyperglycemia and fetal acidemia.26 An example of the effect of maternal hyperglycemia on the CTG of a woman in early labor is shown in Fig. 20.3. The presence of maternal disorders such as pre-eclampsia, the incidence of which is increased with established diabetes, and which is associated with fetal growth restriction, further makes the need for careful fetal monitoring essential. In early labor, CTG monitoring may be performed intermittently if there is maternal normoglycemia (between 4 and 7 mmol/L [72–126 mg/dL]); once labor is established it should be performed continuously.25 If the CTG shows a suspicious or pathologic pattern, the first step should be to check that the maternal glucose is normal. If hyperglycemia is present, then this should be corrected by supplementary intravenous insulin (see chapter 21) and the CTG pattern may well improve as a result (Fig. 20.3). If the mother is normoglycemic, or obtaining normoglycemia fails to correct the CTG abnormality, then other methods of assessing fetal condition should be utilized. A fetal blood sample may be taken if cervical dilatation permits. In the US, fetal blood sampling is not routine practice and other tests such as scalp stimulation are utilized. A systematic review of intrapartum stimulation tests in general pregnant populations has been undertaken.27 Scalp stimulation tests appear to be a moderately good predictive test for fetal acidemia. Interpretation and action on the basis of such tests in the presence of maternal normoglycemia should be the same as for the non-diabetic woman.

Analgesia in labor

As maternal stress may result in hyperglycemia, adequate analgesia in labor may be beneficial for glycemic control. There are no contraindications to the use of opioids or epidurals for analgesia. Indeed, given the increased risk of cesarean delivery with maternal diabetes, the presence of an epidural is usually sufficient for anesthesia (with an appropriate dosage regime) if a cesarean is required.

SPECIFIC OBSTETRIC ISSUES IN THE SECOND STAGE OF LABOR

The main issues in the second stage are similar to those in the first stage, namely concerns about fetal condition and delay. A pathologic CTG in the second stage should be managed in the same way as for the non-diabetic mother, apart from the need for greater caution in the consideration of an instrumental delivery. Delivery of a woman with diabetes should not be conducted by relatively inexperienced staff, unless the latter are closely supervised. In view of the increased risk of shoulder dystocia in all deliveries of diabetic women, whether birth is spontaneous or by low forceps or vacuum delivery, the attendants must be prepared for potential shoulder dystocia. Any early signs of shoulder dystocia should be acted upon using standard maneuvres, such as McRoberts position and suprapubic pressure. If operative delivery (other than low forceps/vacuum) is required, then an experienced obstetrician needs to make an assessment in the operating theater with good anesthesia. Unless there has been significant descent and rotation of the head during the time required to move the woman into the operating theater and to obtain effective anesthesia, then serious consideration should be given to recourse to a cesarean delivery. A relatively difficult delivery of the fetal head may well be followed by an extreme case of shoulder dystocia, followed, in turn, by brachial plexus injury, neonatal asphyxial brain damage, or both. About 10% of cases of documented shoulder dystocia in pregestational diabetes were followed by brachial plexus injury.1