Procedure

Fetal dose (cGy)

Chest X-ray (2 views)

0.00002–0.00007

Abdominal film (single view)

0.1

Intravenous pyelography

≥1

Hip film (single view)

0.2

Mammography

0.007–0.020

Barium enema/small bowel series

2–4

CT scan of the head

<1

CT-based pulmonary angiography

<1

CT scan of the abdomen/lumbar spine

3.5

CT-based pelvimetry

0.25

Researchers have suggested the use of in utero exposure to more than 0.1 Gy of radiation as a threshold for consideration of elective termination of a pregnancy. However, case reports of administration of 0.5 Gy during the first trimester did not demonstrate a substantial risk of fetal malformation. Exposure to a single X-ray during pregnancy is not an indication for a therapeutic abortion. Irradiation of the abdomen and/or pelvis at doses used to treat cancer should be avoided, if possible. However, if such treatment is necessary, the radiation oncologist, the patient, and a maternal fetal medicine specialist must have a frank, open discussion to assess the risk to both mother and child and decide upon a plan of action.

Vaginal Hemorrhage

Acute vaginal bleeding can be life-threatening. Without exception, all women of reproductive age experiencing such bleeding should undergo a urine pregnancy test , as the results significantly impact differential diagnosis of the cause of the bleeding (Fig. 15.1). Such patients should be hemodynamically stabilized, which includes establishing large-bore intravenous access, initiating aggressive fluid resuscitation, and repleting blood products. In cases of significant hemorrhage, transfusion of un-cross-matched blood may be considered.

Fig. 15.1

Differential diagnosis of acute vaginal bleeding. UPT urine pregnancy test

If the pregnancy test is positive, the differential diagnosis for vaginal bleeding during the first trimester includes complete, incomplete, or missed abortion; gestational trophoblastic neoplasia; and molar or ectopic pregnancy. Pelvic examination will help establish whether the cervical os is open or closed, whether products of conception are being expelled by the uterus, the size of the uterus, and whether any appreciable adnexal masses are present. Vaginal lesions that appear to be blue in color should not be subjected to biopsy analysis, as they may be metastatic choriocarcinomas; biopsy may result in uncontrollable hemorrhaging. Also important is determining the maternal blood type, as Rh-negative women should receive Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) to prevent Rh isoimmunization and hydrops fetalis.

Pregnant patients in the second or third trimester who present with vaginal bleeding should receive immediate care managed by an obstetrician. Diagnostic considerations include preterm and normal labor, premature membrane rupture, premature cervical dilatation, placenta previa, placental abruption, and vasa previa. These patients should not undergo vaginal examination until ultrasonographic confirmation of the location of the placenta to avoid inadvertent disruption of a placenta previa or low-lying placenta. They also should be promptly transferred to a labor and delivery unit capable of fetal monitoring and emergent cesarean section.

Women with gestational trophoblastic disease commonly present with vaginal bleeding and a positive pregnancy test. Risk factors for this disease include prior molar pregnancy and advanced maternal age. Upon physical examination, the cervix is usually closed, and the uterus is larger than expected for women at gestational age. Transvaginal ultrasonographic imaging reveals a pathognomonic “snowstorm” pattern of heterogeneous echoes. Rarely, fetal parts may be seen sonographically. Serum levels of β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG ) in these patients are markedly elevated and may subsequently be used to assess response to surgical or medical management. Chest radiography is recommended to rule out the presence of pulmonary metastases. If nodules are seen on chest X-rays, imaging of the brain should be performed. Patients with gestational trophoblastic disease should be admitted to the hospital, with subsequent treatment plans developed in coordination with an obstetrician/gynecologist.

If the pregnancy test for a patient with vaginal hemorrhage is negative, a pelvic examination often suggests the diagnosis for her bleeding. Friable areas of the cervix should be subjected to biopsy analysis, and, if possible, cervical cytologic specimens should be obtained and examined. Cultures for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis should be obtained using an endocervical swab. Significant hemorrhaging from the cervix may be treated with Monsel’s solution or silver nitrate, both of which chemically cauterize areas of bleeding. In cases in which this treatment is unsuccessful, such as those of acute hemorrhaging from a cervical carcinoma, tight vaginal packing may be used. As a last resort, uterine artery embolization, emergent pelvic radiation therapy, and surgical bilateral hypogastric artery ligation may be performed. In addition, thorough vulvovaginal examination should be performed to rule out occult cutaneous malignancies.

If the cervix and vagina appear to be normal and the source of the bleeding is likely supracervical, an endometrial biopsy should be considered. This is especially important for women older than 35 years and those who are morbidly obese, as endometrial pathology is more common in these groups than in others. Transvaginal ultrasonography can identify areas of endometrial thickening and structural anomalies in the uterus, such as leiomyomas. When no anatomic abnormalities are present, the most common diagnosis is anovulatory bleeding; other endocrinologic pathologies (e.g., hypothyroidism) and hematologic dyscrasias (e.g., von Willebrand disease) should be excluded. When significant uterine hemorrhaging occurs, conjugated estrogen (Premarin) may be given intravenously at a dose of 25 mg every 4 h for 24 h or until the bleeding stops. Adequate prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis should be initiated if intravenous estrogen is used given its prothrombotic activity . Alternatives to estrogen administration in women with less acute hemorrhaging are tapered administration of combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive pills and progestin-based therapy alone.

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy is the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths during the first trimester. Early diagnosis is important for maternal welfare because it allows for conservative nonsurgical treatment, thereby preventing potentially catastrophic hemorrhaging associated with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. The incidence of ectopic pregnancy has increased markedly in the United States since 1970, going from 4.5 per 1000 pregnancies to 19.7 per 1000 pregnancies in 1992. However, the number of deaths caused by ectopic pregnancy has decreased 10-fold over the same period, in part owing to improved ultrasonographic detection of it and increasingly sensitive β-hCG assays.

The majority of ectopic pregnancies implant in a fallopian tube, although they may implant on the ovary, cervix, or uterine cornua or in the abdominal cavity. Investigators have identified a number of well-established risk factors for ectopic pregnancy, including prior tubal surgery, genital tract infections leading to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), prior ectopic pregnancy, and in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol. A single ectopic pregnancy increases the risk of a subsequent ectopic pregnancy more than 12-fold, whereas women with a history of either confirmed or suspected PID have a fourfold increased risk. Furthermore, epidemiologic studies have suggested that advanced maternal age, smoking, prior abortion (spontaneous or induced), prior abdominal surgery, multiple sexual partners, prior treatment of infertility, and use of an intrauterine device for contraception are associated with increased risk of ectopic pregnancy.

The classic triad of symptoms of an ectopic pregnancy consists of amenorrhea, vaginal bleeding, and abdominal pain. However, this triad is rare. Therefore, practitioners must suspect ectopic pregnancy in all women who present with vaginal bleeding in the first trimester until an intrauterine pregnancy is ultrasonographically documented. In only 20 % of patients with unruptured ectopic pregnancies, an adnexal mass is palpable upon pelvic examination; in the majority of these patients, physical examination findings are benign. Detection of an adnexal mass in a physical examination may be misleading, because in women with normal pregnancies, the corpus luteum may be large enough to be palpated. Many women with ectopic pregnancies have some degree of vaginal bleeding, but it is usually much less severe than that seen in women having spontaneous abortions. This bleeding results from endometrial sloughing stimulated by β-hCG produced by the ectopic trophoblast.

A patient with a suspected ectopic pregnancy should undergo several diagnostic tests . For example, once a urine pregnancy test is interpreted as positive, the serum β-hCG level should be measured. Although the majority of women with ectopic pregnancies have β-hCG levels lower than those expected for women with normal pregnancies, a single quantitative β-hCG assessment is not diagnostic. Instead, the trend in β-hCG level identified in serial assessments frequently provides detailed information to the clinician. Normally, the β-hCG level increases from 53 % to 66 % every 48 h. If this does not occur, the pregnancy is abnormal. Inappropriate increases in the serum β-hCG level do not indicate where the pregnancy is located, just that the pregnancy is nonviable.

All patients with first-trimester vaginal bleeding should undergo transvaginal ultrasonography. A normal singleton gestation should be visualized when the serum β-hCG level approaches 2000 IU/L. Absence of a gestational sac on transvaginal sonograms when this threshold is reached should increase the suspicion of an extrauterine pregnancy. Occasionally, a “pseudogestational sac” may be seen; such sacs are usually eccentrically located in the midline. The pathognomonic ultrasonographic finding for ectopic pregnancy is a Doppler ring-enhancing (“ring of fire”) mass adjacent to the ovary. In addition, free fluid in the cul-de-sac may indicate a rupture of an ectopic pregnancy.

More than three fourths of women who have ruptured ectopic pregnancies experience marked discomfort upon abdominal examination, with associated cervical motion tenderness upon pelvic examinatio n. Complaints of shoulder pain are particularly ominous, because subdiaphragmatic irritation from hemoperitoneum manifests as referred pain. Intra-abdominal hemorrhaging can occur rapidly and be severe; as a result, hypovolemia can occur quickly. Dizziness, tachycardia, and hypotension should be evaluated immediately, and resuscitation with blood products and intravenous fluids should be initiated during preparations for transport to surgery. A number of patients will be stable enough to undergo laparoscopic salpingectomy or salpingostomy, but hemodynamically unstable patients must undergo laparotomy.

Medical management is appropriate for the majority of patients with ectopic pregnancies. Physicians have used methotrexate to treat ectopic pregnancies since 1982, with success rates reported to be as high as 94 %. Single-dose methotrexate is most effective when the initial serum β-hCG level is less than 5000 IU/L, and it may be given as a series of doses, if necessary. Absolute contraindications for treatment with methotrexate include a ruptured ectopic pregnancy; a patient who is unstable; abnormal hepatic, renal, or hematologic function; and immunodeficiency. Relative contraindications include a gestational sac larger than 3.5 cm in diameter and embryonic cardiac motion. Single-dose methotrexate is administered at 50 mg/m2 via intramuscular injection, and the β-hCG level is checked on days 4 and 7 after treatment. The β-hCG level should decrease by 15 % from day 4 to day 7. If this decrease does not occur or the β-hCG level plateaus or increases, a second dose of methotrexate can be given. β-hCG in serum should be measured until it reaches a nonpregnant level (less than 5 IU/L).

The key to successful management of an ectopic pregnancy is early diagnosis. Physicians evaluating women of reproductive age who present with positive pregnancy tests and either vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain should have a high index of suspicion for and make vigorous efforts toward early diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy.

Genital Tract Infections

Patients who present to the emergency room with complaints of lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, or fever must be evaluated for the presence of a pelvic or vulvovaginal infection. History of the present illness, a gynecologic and gastrointestinal review of systems, and sexual history should be obtained. The vulva, vagina, and cervix should be thoroughly inspected to determine if infection is present in the lower or upper genital tract, as treatment strategies differ by location. Bimanual examination should include assessment of cervical motion tenderness, adnexal pain, and pelvic masses, and the vaginal pH should be determined using litmus paper (normal adult vaginal pH, 4.0). A vaginal discharge swab should be obtained to perform microscopic review of a wet mount. To prepare the wet mount, vaginal discharge specimens are smeared onto a slide, a 2-mL drop of normal saline is applied to the slide, and a coverslip is placed on the slide. If a mycotic infection is suspected, the discharge specimen should be suspended in 10 % KOH prior to examination under the microscope. Wet mounts are diagnostic for several infections, including trichomoniasis. When appropriate, cervical cultures for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae should be obtained. Fungal, anaerobic, and aerobic cultures may be indicated for patients with recurrent or persistent infections.

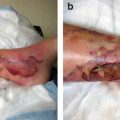

Bartholin Gland Abscess

The Bartholin glands are paired structures located at the distal vagina whose ducts communicate with the vestibule between the labia minor and hymen. The ducts open at approximately the 5 and 7 o’clock positions. Obstruction of these ducts can cause Bartholin cysts, which are palpably nontender with no overlying erythema. Usually, the patient will complain of a “bulge” near her vagina. Bartholin cysts can be managed conservatively, and patients are encouraged to use sitz baths several times a day, as the warm water in these baths frequently loosens the proteinaceous material occluding the ducts. If a Bartholin cyst becomes infected, an abscess may form. Such abscesses are usually polymicrobial, with Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus species the most commonly isolated pathogens; Chlamydia and Neisseria species are rarely causative pathogens. Patients with Bartholin abscesses usually present with painful erythematous swelling adjacent to the posterior fourchette. Areas of fluctuation may be palpated at the site, and inguinal adenopathy may be present. The standard treatment of such abscesses consists of incision and drainage, which can be performed under local anesthesia. A small incision is usually sufficient to facilitate drainage of purulent material. Cultures of the abscess cavity should be obtained, and patients should begin taking an oral broad-spectrum antibiotic. A Word catheter may be placed in the abscess cavity to facilitate epithelialization of a tract independent of the Bartholin duct to prevent abscess recurrence. Rarely, Bartholin abscesses can progress to widespread cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis, at which point hospitalization, intravenous antibiotic administration, and surgical debridement may be necessary.

Trichomonas Vaginitis (Trichomoniasis)

Trichomoniasis is caused by the flagellated protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis and is the most common nonviral sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States. Trichomoniasis is diagnosed more often in women than in men because it tends to be asymptomatic in the latter. Symptoms include a yellow or green vaginal discharge, vaginal itching, dysuria, and dyspareunia. Upon physical examination, a frothy discharge is present, and the vaginal walls are typically erythematous. The classic strawberry cervix may be noted, which is caused by subepithelial hemorrhages. The vaginal pH is usually basic (5.0–6.5), and the discharge may be malodorous.

Trichomoniasis is definitively diagnosed using a wet mount preparation. Motile flagellated organisms in such preparations may be directly visualized under a microscope. The T. vaginalis microbe is larger than a white blood cell, and leukorrhea may accompany the infection. Trichomonas culture is rarely indicated, although an endocervical mucus specimen should be obtained and examined to rule out concurrent infection with N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree