Obesity and Nutrition

Jeffrey I. Mechanick

Elise M. Brett

DEFINITION

Obesity is a chronic disease diagnosed when an adult person has a body mass index (BMI) of 30 to 34.9 (class I), 35 to 39.9 (class II), more than 40 (class III, “extreme obesity”), more than 50 (class IV, “super obesity”), or more than 60 kg/m2 (“super-super obesity”). BMI is not a direct measure of adiposity but rather a derived value correlated with total body fat and risk for certain complications. BMI is calculated as the weight in kilograms, divided by the height in meters squared. Alternatively, one can calculate the weight in pounds, divide by the height in inches squared, and multiply by 703. Risks for cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes (T2DM), and hypertension are further defined by subgrouping overweight BMI (25-29.9 kg/m2) or obese BMI categories into those with increased abdominal obesity by waist circumference: more than 102 cm (40 inches) for men and 88 cm (35 inches) for women or by waist-to-hip ratio: more than 0.9 for men and more than 0.85 for women. However, optimal metrics for risk stratification have not been determined. For instance, in a German population, waist-to-height ratio was more predictive of CVD risk and mortality than waist-to-hip ratio, waist circumference, or BMI [1]. Additionally, among patients considered for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RGB) bariatric surgery, the obesity surgery mortality risk score (based on BMI ≥50 kg/m2, male gender, hypertension, risk for pulmonary embolism, and age ≥45 years) has been shown to predict postoperative mortality [2]. In pediatric and adolescent persons, BMI percentiles for ages 2 to 17 years are used. “Overweight” persons are those between the 85th and 95th percentiles, and “obese” persons are above the 95th percentile [3]. Obesity in youths is defined as BMI of 95th percentile or BMI of 30 kg/m2, whichever is lower. Different protocols for intervention are recommended based on these categories. For children less than 2 years of age, BMI normative values are not available.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

More than 1.7 billion persons worldwide are overweight or obese [4]. The prevalence of overweight or obesity among United States adults in 2007 to 2008 was 68%; obesity, 33.8%; and class III obesity, 5.7%, with women generally having a higher prevalence of obesity compared with men [5]. The prevalence of obesity in children or adolescents during the same time period was 16.9% [6] and 17% overweight [7]. In 2006 to 2008, non-Hispanic blacks had the greatest prevalence of obesity (35.7%), followed by Hispanics (28.7%), and non-Hispanic whites (23.7%) [8]. The differences were greater among women than men. The 30-year risks of being overweight are more than 91% for men and 73% for women, of being obese are more than 47% for men and 38% for women, and of having class III obesity or more are more than 4% for men and 6% for women [9]. Increasing BMI is associated with the prevalence of T2DM, heart disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, asthma, arthritis, certain cancers (colon, cervix, breast, prostate, and lung), venous thromboembolic disease, sleep apnea, and poor general health [10, 11]. In the 2010 study by Berrington [12], both overweight and obesity are associated with increased all-cause mortality.

Irrespective of BMI, the accumulation of fat in the abdomen, pancreas, liver, and muscle is strongly associated with the metabolic complications of obesity [13], hypertension [14], and CVD [15]. Depending on the definition used, visceral obesity is part of the “metabolic” or “insulin-resistance” syndrome, along with hypertension, impaired glucose regulation, dyslipidemia, and other biomarkers for prothrombotic and proinflammatory states [16]. Metabolic syndrome is a univariate predictor of coronary heart disease (odds ratio, 2.07) [17]. The INTERHEART study was the first large multiethnic study to show that metabolic syndrome is a risk for MI, and the risk of MI increased as more component factors were present [18].

Metabolic syndrome also predicts development of T2DM, and weight reduction of 3 to 6 kg by lifestyle change or medication (orlistat or metformin) reduces the risk for T2DM [19, 20, 21]. In a recent study of over 32,024 mostly Caucasian Americans, 13.1% of women and 30.5% of men had metabolic syndrome defined by NCEP ATIII criteria. However, the definition, implications, and even semantics of this syndrome have been challenged [22, 23].

ETIOLOGY

Obesity is the result of certain genetic and environmental factors that result in positive energy balance (calorie consumption > energy expenditure). Heritability accounts for 30% to 70% of the variation in body mass within a population, but consistently replicated common genetic variants have not been associated with common obesity [24, 25, 26]. Genetic factors determine set points for appetite, intermediary metabolism, and physical activity behavior. Environmental factors that produce a state of energy surfeit consist of (1) prenatal factors; (2) availability of inexpensive, palatable, energy-dense foods; (3) large portion sizes; (4) social, economic, ethnic, and cultural pressures to overconsume food; (5) media advertising; and (6) sedentary lifestyle [27]. It has been proposed that increased consumption of energy-dense foods (relatively low in water content [dry], high in fat content, and particularly found in “fast foods”) is a major contributor to the obesity epidemic. One theory suggests that humans have a weak ability to recognize high-energy-density foods and to downregulate the bulk of food ingested to avoid consumption of excess calories [28]. However, a critical review of the data concluded that a causal relation has not been clearly demonstrated [29]. Similarly, high-fat diets have not been shown to cause excess body fat in the general population [30], although genetically susceptible individuals may exist [31].

Interestingly, breakfast consumption, especially those including a ready-to-eat (RTE) cereal, has been shown to correlate with lower BMI and lower risk of obesity in women, as compared with skipping breakfast [32]. Ruxton et al. [33] asserted that a breakfast meal high in fiber and low in fat represents a beneficial nutritional profile and decreased risk for obesity, but longitudinal studies are required to confirm this association.

Interestingly, breakfast consumption, especially those including a ready-to-eat (RTE) cereal, has been shown to correlate with lower BMI and lower risk of obesity in women, as compared with skipping breakfast [32]. Ruxton et al. [33] asserted that a breakfast meal high in fiber and low in fat represents a beneficial nutritional profile and decreased risk for obesity, but longitudinal studies are required to confirm this association.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

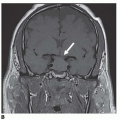

Appetite centers in the paraventricular nucleus, arcuate nucleus, and lateral hypothalamus play a central role in allowing overconsumption of calories. Ghrelin is orexigenic (stimulates appetite), is produced by the stomach, and has a dominant role over leptin, which is anorexigenic (inhibits appetite) and is produced by adipose cells. In the arcuate nucleus, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase, agouti-related protein, neuropeptide Y, γ-aminobutyric acid, and galanin inhibit the satiety centers of the arcuate and paraventricular nuclei and stimulate the feeding center of the lateral hypothalamus, which also decreases energy expenditure. Peptides in the arcuate nucleus satiety center include proopiomelanocortin (POMC), α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, cocaine- and amphetamine-related transcript, and neurotensin. Gut hormones, such as insulin, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), peptide YY, and cholecystokinin, inhibit the feeding centers, activate the satiety centers, and increase energy expenditure. Polymorphisms that affect secretion or signal transduction of any of these pathways can influence the body composition set point. In addition, recent studies have implicated sleep disturbance in the pathophysiology of obesity. Brondel et al. [34] found that one night of reduced sleep increased food intake greater than physical activity-related energy expenditure in healthy men. At least one randomized study is underway to determine if extension of sleep duration affects BMI [35].

Once environmental factors exploit a genetically determined predisposition in body composition that creates obesity, an inflammatory state ensues. Adipokines (interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, leptin, and adiponectin) are products from adipose tissue that contribute to this inflammatory state with obesity. Hyperinsulinemia, which leads to decreased cardioprotection, is also associated with obesity and a proinflammatory state [36]. Thus, pathogenic adipose tissue, or adiposopathy, appears to play an important role in the development of obesity.

TREATMENT

The initial goal of therapy is to identify and treat associated CVD risk factors (high blood pressure, elevated glucose, dyslipidemia) and to prevent further weight gain. Then a realistic goal for weight loss should be determined. In general, an initial goal of 10% weight loss over a 6-month period with maintenance of lean body mass is feasible and reduces risk. Typically, faster weight loss occurs with diuresis during the first 2 weeks, followed by slower weight loss. By 6 months, weight loss plateaus, and patients may become discouraged. Patients should be reminded of the metabolic changes occurring with weight loss and the need for a maintenance program. Weight loss by as little as 3.8% in 2 years with dietary intervention was associated with salutary effects on cardiovascular parameters, and partial weight regain diminished these effects [37]. Although some observational studies have demonstrated an association of weight loss with mortality, the randomized ADAPT study demonstrated that “intentional” weight loss of overweight/obese (BMI > 34) older (median age 69 years) adults was not associated with increased risk for mortality and may even decrease the mortality risk [38].

Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes

The nonpharmacologic and nonsurgical management of obesity involves behavioral modification, healthy eating, and increased physical activity. This should be first-line therapy for obesity and continued throughout a person’s life not only to enhance other therapies but also promote general health. In a pragmatic PRCT, intensive medical therapy (900 kcal liquid diet for up to 12 weeks, group behavioral counseling, structured diet, and choice of pharmacotherapy) of adults over 20 years with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or higher was associated with significant amounts of weight loss [39]. In obese adolescents, modest lifestyle-only changes are associated with a redistribution of body composition, improved insulin sensitivity, and decreased markers of inflammation [40].

Behavioral

Behavioral therapy is an essential requirement for all weight management interventions. Patients learn how to overcome obstacles and improve long-term adherence to lifestyle changes through behavioral therapy. Strategies include healthy eating, increased physical activity (though a recent study indicated that resistance training alone has little effect, if any, on the psychosocial profile [41]), recognizing unhealthy lifestyle patterns, self-monitoring (keeping logs), stress reduction, stimulus identification and control, setting goals and offering rewards, problem solving, and social support. Behavioral therapy can induce a 5% to 10% weight loss and is more effective than a very-low-calorie diet alone [42, 43, 44].

Commercially available weight loss programs, involving portion control and education, can reduce CVD risk [45], and larger clinical trials are currently underway to confirm these findings [46]. In the PREMIER trial, lifestyle interventions were found to reduce 10-year CVD risk by 12% to 14% [47]. These programs need to be culturally sensitive in order to be effective in different patient populations [48]. Participation in group settings in the workplace has been shown to be effective [49]. Incorporation of self-determination principles in behavioral therapy is also important [50]. In overweight/obese postmenopausal women, restrictive messages to limit high-fat foods induced greater weight loss than nonrestrictive messages to include fresh fruits and vegetables [51].

In adolescents with a mean BMI of 37.6 ± 3.3 kg/m2, behavioral therapy favorably redistributed body composition in the absence of weight loss while also improving insulin sensitivity and reversing the inflammatory state [40]. It is interesting that there is a difference between “liking” a food and “wanting” to eat that food; moreover, the pattern of this disparity varies with a patient’s BMI [52]. For instance, consuming high-energy-density snack foods is not associated with decreased intake of that snack over time in obese patients, even though “liking” that food reportedly decreases [52]. In a meta-analysis of randomized studies of children, behavioral family-based treatment led to sustained weight loss [53]. Even a simple reduction in television viewing by 50% over a 3-week period of time can be associated with significant increases in energy expenditure without increases in energy intake [54].

Other benefits of behavioral therapy include improved biomarkers of vascular inflammation [55, 56] and improvement in the weight loss response to pharmacotherapy [42, 57, 58]. In a randomized trial of 91 community members, use of computer-assisted dieting interventions were found to be associated with initial weight loss, but self-management training was needed for support maintenance [59]. Education about nutrition facts labels has also been associated with reduced energy intake [60]. Brochures and active education had comparable beneficial effects on the nutritional habits of obese pregnant women [61].

Weight gain can be expected with discontinuation of behavioral therapy. Sequential behavioral therapy for weight control after a program for smoking cessation may have superior results compared with concurrent weight control and smoking cessation interventions [62].

Healthy Eating and Nutrition

Patients with obesity should be encouraged to restrict calories while following basic principles of healthy eating. For most patients, reducing intake by 500 kcal/d leads to a 0.5- to 1-lb weight loss per week and is associated with no increased risk. Low-energy diets can also improve endothelial function [63] and obesity-related comorbidity symptoms, such as obstructive sleep apnea [64]. Diets should be low in saturated fat (<10% total calories) and dietary cholesterol (<300 mg/d) with minimal trans fatty acids and the majority of dietary fat consumed as monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) to decrease the risk of atherosclerosis [65]. However, the type of dietary fat consumed does not appear to affect postingestion satiety or energy intake [66]. The incorporation of larger portions of low-energy-dense foods, such as fruits and vegetables, provides essential fiber and phytonutrients while maintaining satiety and restricting energy intake [67]. Including a whole grain RTE oat cereal as part of a dietary program was associated with improved waist circumference and fasting lipid levels [68]. The consumption of caloric beverages with a standard meal is best avoided, as they do not increase satiety and only increase calories consumed [69].

The optimal macronutrient distribution for weight loss has been frequently debated and remains controversial. It is most likely that one approach will not suit all patients. Four randomized controlled studies demonstrated greater weight loss at 6 months, but not by 1 year, with low-carbohydrate diets [70, 71, 72, 73, 74]. A plant-based (vegan), low-fat diet, without any prescribed limits on portion size or energy intake, was associated with greater weight loss (-5.8 kg vs. -3.8 kg) compared with a control diet [75]. In a meta-analysis, low-fat diets were not found to be superior to calorie-restricted diets [76]. TCF7L2 is a necessary transcription factor for proglucagon gene expression and GLP-1 synthesis, which is higher after ingesting fat than carbohydrate. Obesity modifies the association of TCF7L2 with T2DM. In a PRCT conducted by Grau et al. [77], patients on average experienced similar effects of a -600 kcal/d hypoenergetic high-fat (40%-45% energy), compared to those on a low-fat (20%-25% energy), diet on body weight/composition and insulin resistance. However, those patients who were homozygous for the TCF7L2 rs7903146 T-risk allele had less of these effects with the high-fat diet [77]. This observation illustrates the emergent science of nutrientgene interactions relevant to obesity research.

Some studies suggest that diets higher in protein (25%-30%) may increase satiety and result in lower caloric intake in a free-living environment [78, 79]. The mechanism for the satiating effect of dietary protein is unclear and not related to postprandial ghrelin secretion, as previously thought [80]. One study showed a greater decrease in triglycerides and reduced fat mass with a high-protein, low-fat diet relative to a conventional high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet, but the total weight loss was equivalent after 12 weeks [81]. Supplementation with whey protein (27 g PO b.i.d. × 12 weeks) was associated with improved fasting lipid and insulin levels in overweight/obese patients [82].

High-protein diets deliver a marked acid load to the kidney and thereby increase the risk for bone loss and kidney stones [83, 84], although high-dose calcium supplementation during short-term calorie restriction can attenuate bone resorption [85]. High protein consumption can also accelerate chronic kidney disease (CKD) and should be avoided in patients with baseline elevated creatinine and used

with caution in patients at high risk for CKD, such as those with diabetes or hypertension [86]. Nevertheless, a recent PRCT of 68 obese patients with normal renal function at baseline failed to demonstrate any adverse effect on renal function of a very-low (4%) carbohydrate diet with 35% protein [87].

with caution in patients at high risk for CKD, such as those with diabetes or hypertension [86]. Nevertheless, a recent PRCT of 68 obese patients with normal renal function at baseline failed to demonstrate any adverse effect on renal function of a very-low (4%) carbohydrate diet with 35% protein [87].

Weight loss (2.1-3.3 kg over a 1-year period) was comparable among various commercially available diets: Atkins (carbohydrate restriction), Zone (macronutrient balance), Weight Watchers (calorie restriction), and Ornish (fat restriction); successful weight loss was associated with adherence and cardiac risk factor reduction [88]. However, in a more recent study by Foster et al. [89], a lowcarbohydrate diet (20 g/d) with low-glycemic-index foods and unlimited fat and protein was associated with higher HDL cholesterol levels at 2 years compared with a low-fat (≤ 30 g/d), low-energy (1,200-1,800 kcal/d) diet. All patients in the study received behavioral therapy, and both groups demonstrated weight loss (7%) at 2 years [89]. In addition, low-carbohydrate diets may have detrimental effects on vascular function and CVD risk [90, 91].

Very-low-calorie diets (VLCD; <800 kcal/d) or “protein-supplemented modified fasts” and low-calorie diets (LCD; 800-1,500 kcal/d) are associated with comparable rates of weight loss, although more weight is lost initially with VLCDs. In a large, multicenter study [92] involving 1,389 patients followed up for at least 1 year on a VLCD providing 600 to 800 calories per day, mean weight loss was -6.9 ± 2.6 kg at 1 month, -12.3 ± 5.3 kg at 3 months, and -13.1 ± 8.0 kg at 12 months. The weight loss was primarily fat mass, as determined by bioimpedance analysis [92]. VLCDs require protein sources of high nutritional value and supplementation of vitamins and micronutrients, including sodium, potassium, calcium, iron, and magnesium. VLCDs are safest when monitored by a physician as part of a comprehensive weight reduction program. VLCDs are contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation, major psychiatric disease, severe systemic disease, and type 1 diabetes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree