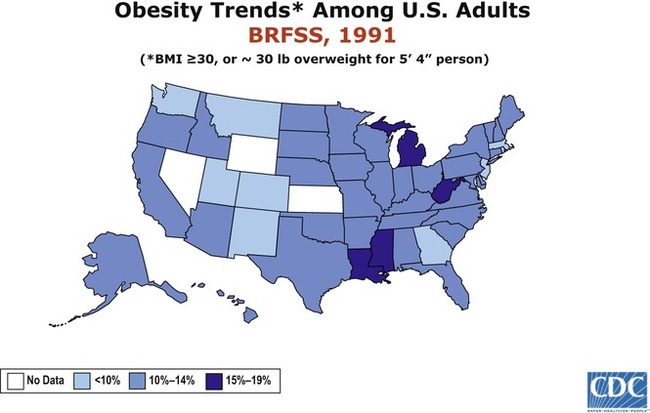

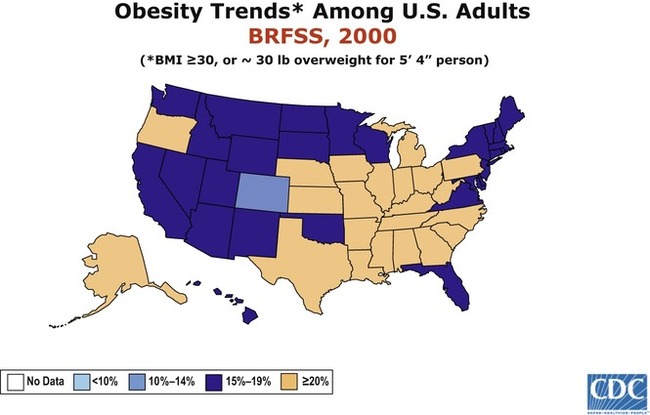

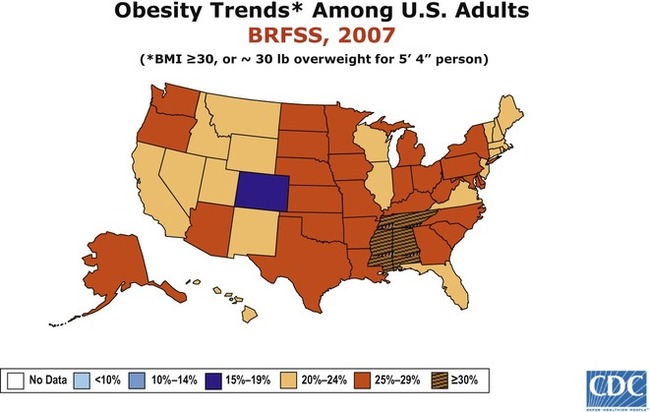

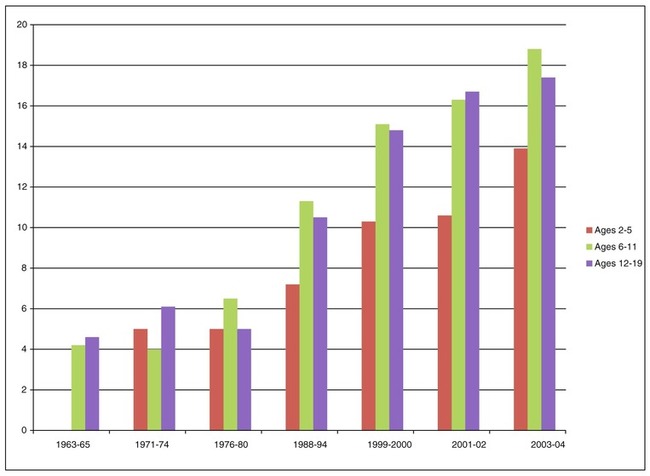

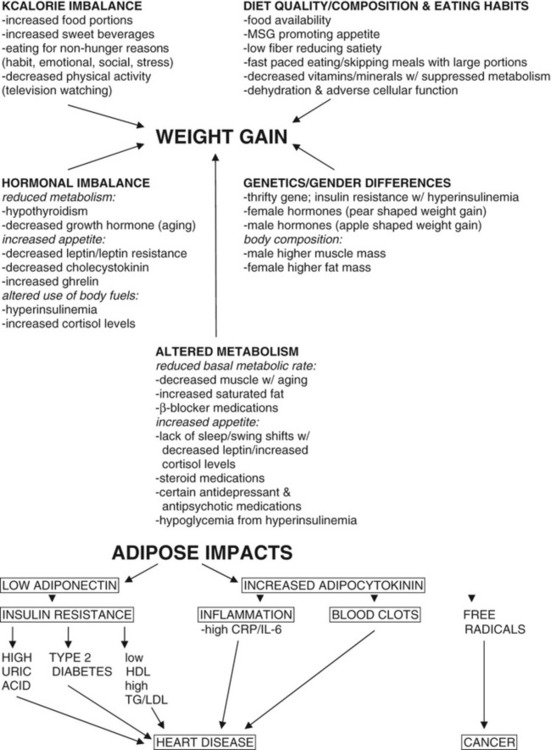

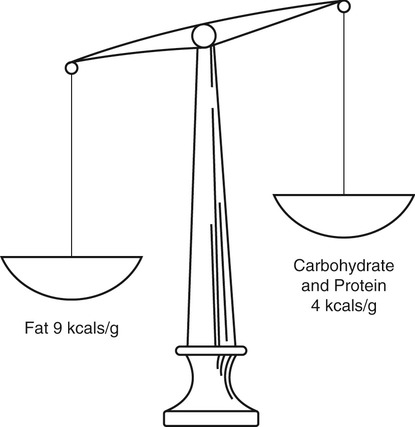

After completing this chapter, you should be able to: • Describe obesity and discuss its prevention and treatments. • Recognize healthy weight management practices. • Relate the importance of physical activity to healthy weight management. The World Health Organization has referred to obesity as a “global epidemic” since the 1990s, but the significant rise in obesity began to appear in the 1980s. The incidence of obesity and overweight in the United States currently affects about two thirds of the adult population (Figure 6-1). The Healthy People 2010 goal of 15% obesity rate is not expected to be met if current trends continue. It is anticipated that white persons will have a rate in the 30% range, along with African American men. African American women are expected to have an obesity rate of over 50% by this time (Wang, Colditz, and Kuntz, 2007). Promotion of physical activity is critical in the prevention of obesity. Historically, when people had to forage for their food, they expended energy. It has been estimated that Native Americans ran 60 miles a day while hunting. Our sedentary lifestyles, in combination with an increased intake of simple carbohydrates and saturated fat, appear to be the driving force behind the development of obesity. Physical activity promotes an increase in energy expenditure and allows better weight stability than control of food intake (Levitsky and colleagues, 2005). Increased intake of kilocalories (kcalories or kcal) through larger food portions and high intake of sugar-based beverages (see Figures 6-2 and 1-1) along with reduced physical activity is the driving force in the obesity epidemic. With decreased intake of fiber-based foods, the ability to recognize the feeling of fullness is diminished. Add to this a fast pace of eating, and the result is a pattern of overeating with resultant weight gain. It is the excess fat in the abdominal area, as found with the metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis (see Chapters 5 and 7), that is linked with health problems. The term metabolic obesity is suggested in reference to excess body fat in the abdominal area. Metabolic obesity is more prominent in white men, African American women, Asian Indians, and Japanese (Hamdy, Porramatikul, and Al-Ozairi, 2006). Metabolic obesity is associated with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, kidney disease, and certain cancers (Flegal and colleagues, 2007). Other issues with obesity include the following: The Body mass index (BMI) is considered one of the simpler tools that more accurately determine appropriate body weight. The BMI has replaced an older standard, the Metropolitan Life Height and Weight Tables, because of inherent shortcomings such as ethnic bias and emphasis on mortality with death statistics rather than morbidity with a variety of health problems. The BMI is now the preferred standard for determining appropriate body size. Its formula was developed over a hundred years ago by a mathematician named Quetelet. As only a mathematician can, he realized that dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2) gives a better sense of body proportion. An alternative calculation to derive the BMI is lb/in2 × 703 (Kushner and Jackson Blatner, 2005). The BMI has its own shortcomings, because it does not take into account body composition. A bodybuilder, for example, may have a high BMI number but is not obese because body fat levels are low. An ideal body weight equates to a BMI between 19 and 25 with an upper limit of 27—see Appendix 9 on the Evolve website for a BMI nomogram. Someone who is underweight has a BMI of less than 19. A BMI of 15 equates to 20% underweight, which is a dangerously low level that can result in death (see Chapters 12 and 13 for information on eating disorders). In populations at high risk of the metabolic syndrome, a BMI of 21 or less is advised (James, 2008). A BMI under 30 may be acceptable if there are no health problems. Three classes of obesity, based on BMI, are now being used: Class I obesity: BMI greater than 30 Class II obesity: BMI greater than 35 Class III obesity: BMI greater than 40 (also now referred to as extreme obesity). Rapid weight loss is not advised for anyone, but especially not for the elder population (see Chapter 13). Slow weight loss of approximately More precise methods of determining body fat percentage include the following: • Skinfold measurements taken at different body sites (see Figure 1-9) • The bioelectric impedance machine, which sends an imperceptible electric current through the body; results vary based on levels of hydration, because water is the medium through which the electrical current flows • Underwater weighing (usually done only at research centers) Figure 6-3 shows the increased rate of obesity among children and adolescents from 1963 to 2004. Regions where obesity was once thought impossible are now showing the effects of excess caloric intake such as in Asia. There are higher amounts of obesity among minority populations. This may be related to increased rates of insulin resistance in these populations along with environmental factors. Many factors can affect weight in an individual: eating habits, cooking methods, family customs, emotional problems, peer pressure, food advertising, and food availability all have influence on caloric intake, whereas factors such as age, gender, heredity, body composition, hormonal makeup, physical activity, and even occupation all affect energy expenditure (Figure 6-4). Obesity is generally thought to occur as a result of long-term positive energy balance for individual needs. In other words, weight gain occurs when caloric intake exceeds expenditure (Table 6-1) over an extended period. This was the basis for the low-fat message beginning in the 1980s. Because 1 g fat has 9 kcal as compared with 1 g carbohydrates at 4 kcal, it was logical to conclude that kcalorie intake would go down when carbohydrate replaced fat kcalories (Figure 6-5). What was not considered is that sugar intake could continue to increase off-setting the kcalorie savings from less fat. Table 6-1 Kilocalories Expended per Hour for Various Types of Activities *A range of caloric values is given for each type of activity to allow for differences in activities and in persons. Of the sedentary activities, for example, typing uses more kilocalories than watching TV. Some persons will use more kilocalories in carrying out either activity than others; some persons are more efficient in their body actions than are others. Values closer to the upper limit of a range will give a better picture of kilocalorie expenditures for men, and those near the lower limit a better picture for women. From U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA): Food and your weight, Home and garden bulletin No. 74, Washington, DC, USDA. Increased use of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), after the embargo on sugarcane from Cuba, coincided with the obesity epidemic. Widespread use of HFCS in beverages has been linked to rising obesity rates, but this is most likely due to larger portions of sugar-based beverages consumed (see Figure 1-1) and the HFCS they contain, and not due to a physiologic cause. A study in Canada found, overall, there were half as many preschool-age children who were overweight by age 5 years who did not drink sugar-based drinks as compared with those preschool children who had sweetened drinks four or more times in a week. In this same age-group, children from low-income homes who regularly drank sugar-based drinks were found to be more than three times as likely to be overweight by the age of 5 years compared with children living in higher-income homes who were not regularly consuming sugar-based drinks (Dubois and colleagues, 2007). In a study of women, when a caloric beverage was consumed with the meal, energy intake was about 100 kcal greater than when a noncaloric beverage or no beverage was consumed (DellaValle, Roe, and Rolls, 2005). Replacing all sweet beverages with drinking water has been associated with a decrease in total energy of 200 kcal/day. Satiety was still found to occur such that increasing kcalories from other sources did not happen (Stookey and colleagues, 2007). Portion sizes are likely the driving force behind obesity. Large portions will promote hyperinsulinemia among those who genetically tend to have insulin resistance. Typical portion sizes in a self-selected study of young adults in a college setting found portions to be significantly larger from those selected by young adults in a similar study conducted two decades ago (Schwartz and Byrd-Bredbenner, 2006). Kcalorie needs are altered based on level of physical activity. The Meals, Ready to Eat (MREs) in the military are planned for 3500 to 5000 kcal, which is similar to the estimated intake of the old-time loggers before the advent of power tools. Persons nowadays who have desk jobs require far fewer kcalories to maintain their weight. Most adults require about 2000 kcal for weight management, as reflected in the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) on food labels and in the MyPyramid guidelines (see Chapter 1). The reduced physical activity associated with watching television for 2 or more hours daily increased odds of overweight by 50% for adolescents (Fleming-Moran and Thiagarajah, 2005). Reduced activity not only limits kcalorie expenditure, it promotes insulin resistance, thereby promoting hyperinsulinemia. Type of dietary fat has been found to affect metabolism differently. The monounsaturated fat oleic acid (see Chapter 2; Table 2-5) was found to increase daily energy expenditure in men, and increase fatty acid oxidation in women, whereas there was a decrease with the saturated fat palmitic acid (see Chapter 2) in the diet (Kien and Bunn, 2008). Increases in dietary palmitic acid have been found to significantly decrease fat oxidation and daily energy expenditure by as much as 275 kcal equivalent, whereas substitution with oleic acid has the opposite effect (Kien, Bunn, and Ugrasbul, 2005). The omega-3 and polyunsaturated n-6 fatty acids have been related to reduced fat cell size, whereas the saturated fatty acids significantly increase fat cell size and number. The n-9 fats were related to reduced numbers of fat cells (Garaulet and colleagues, 2006). Increased chewing of foods due to their level of hardness has been associated with smaller waist size (Murakami and colleagues, 2007). This may be due more to the increased chewing than to the actual degree of hardness. Individuals who eat slowly, by chewing more, typically note earlier satiety with consequent reduced intake of food. Frequency of eating also plays a role. Young children in the United States who eat less often during the day consume larger portion sizes than children who eat more often during the day. Among infants, total kcalorie intake varies based on needs, suggesting an innate ability to regulate kcalorie intake. By toddler age, this self-regulation was found to be less effective. This suggests environmental cues tend to override physiologic cues of hunger and satiety (Fox and colleagues, 2006). Adults who eat smaller, more frequent meals also typically have better weight management. This is in part due to suppressed production of the hormone cortisol (see section below), which is released if blood glucose levels begin to drop. Avoiding long intervals without eating helps to keep blood glucose level stable, thereby suppressing release of cortisol. Gender has a role in weight. Hormonally women tend to carry weight in their hips and thighs and men in their abdominal region. Men generally have an easier time losing weight when they diet, and this is believed due to their higher level of muscle mass, which is more active tissue than is adipose tissue (body fat). There even appears to be a gender difference in food preferences. Obese women have been noted to have a higher intake of carbohydrates, whereas obese men generally have been found to have a higher intake of fat (Duvigneaud and colleagues, 2007). Sex-linked steroids (see section below) found in adipose tissue help to regulate location of body fat. The ratio of estrogen to androgens helps determine pear-shaped (carrying weight in the thighs, as typically found with women) versus apple-shaped (central obesity, as found more frequently with men and the metabolic syndrome) patterns of body fat (Wake and colleagues, 2007). In obesity, body proteins have been found to be altered. Plasma tryptophan concentrations are decreased due to increased tryptophan breakdown from chronic immune activation and altered enzyme functioning. Furthermore, these metabolic changes with tryptophan may promote reduced serotonin levels and cause mood disturbances, depression, and impaired satiety, ultimately leading to increased caloric uptake and obesity. The lowered tryptophan levels can be considered the driving force for food intake (Brandacher and colleagues, 2007). The protein taurine is important for increased resting energy expenditure. Obesity tends to lower body content of taurine because of altered enzyme functioning. Supplementing with taurine may be helpful in controlling obesity (Tsuboyama-Kasaoka and colleagues, 2006). Appropriate hydration best allows cellular metabolism. Dehydration impairs the use of insulin and is related to insulin resistance (Schliess and Häussinger, 2003). Insulin is medically defined as being lipogenic (from lipo, meaning fat, and genic, meaning genesis or creation), and it inhibits lipolysis (breakdown of body fat). Persons with insulin resistance, as found with the metabolic syndrome, will tend to have hyperinsulinemia with a high carbohydrate intake. The basis of weight gain among persons with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia is that lean tissue (muscle) versus adipose tissue (body fat) has a different level of resistance. Insulin resistance is found with lean tissue. Adipose tissue has high insulin sensitivity (Sebert and colleagues, 2005). Therefore the use of glucose is impaired at the cellular level of lean tissue but not with adipose tissue. There appears to be enhanced conversion of kcalories to body fat storage from hyperinsulinemia, resulting in less kcalories available for physical energy needs. This can set up a cycle of reduced physical activity but increased eating because of the feeling of hunger, resulting in weight gain (Lustig, 2006b). The situation is worsened once a person is overweight. In normal-weight individuals, postprandial insulin release appears to promote the sensation of satiety, but there is a suppressed effect in overweight individuals. This may be due to insulin resistance in the central nervous system (Flint and colleagues, 2007). Hyperinsulinemia during pregnancy is associated with increased gestational weight gain and increased postpartum weight retention (Scholl and Chen, 2002). • Kcalories going toward body fat storage • Interference with leptin’s function of appetite reduction • Promotion of food as a reward to the system due to altered metabolism of dopamine (a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system) (Lustig, 2006a). In a study related to questions of swing-shift work schedules, it appears that the level of leptin is artificially decreased at times of awakening and is believed to contribute to the prevalence of obesity in swing-shift populations (Shea and colleagues, 2005). Inadequate amounts of sleep are found in overweight and class I or II obese individuals. A cause-and-effect relationship has not been established, but lack of sleep and the associated overweight is suspected to result from changes in leptin and other hormonal levels (Vorona and colleagues, 2005). Causes of central obesity, as found with the metabolic syndrome, include glucocorticoid (hormones released by the adrenal gland) excess. With insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, excess cortisol (the primary glucocorticoid hormone that catabolizes protein) production is promoted in order to prevent hypoglycemia through the process of gluconeogenesis—see Chapter 2. This may be the factor behind weight gain with chronic skipping of meals. Adequate amounts of deep sleep are needed to help suppress cortisol release. This may also contribute to weight gain among individuals with swing-shift work schedules. A minimum of 6 hours of continuous sleep is needed, and most persons need 8 to 9 hours of sleep to function at peak levels. Adipose tissue is further recognized to function as an endocrine gland producing its own hormones. Some of these substances are termed adipocytokines and may promote maintenance of body fat once it has accumulated. Adipocytokine hormones promote the following (see Figure 6-4): Adipose tissue inflammation is suspected as the cause of obesity-related health problems. Markers of chronic inflammation such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) are found with insulin resistance, obesity, and low levels of an antiinflammatory hormone, adiponectin. Adipose tissue further produces free fatty acids that contribute to insulin resistance (Schinner and colleagues, 2005). The hormonal impact of adipose tissue may explain why it is more difficult to lose weight than it is to gain weight initially. As the level of central obesity increases, adiponectin levels go down, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level is decreased, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglyceride levels are increased (Kwon and colleagues, 2005). This may be the connection with obesity and atherosclerosis, because the early stage of atherosclerosis is found with low serum levels of adiponectin (Pilz and colleagues, 2005). Low levels of this hormone have also been associated with type 2 diabetes and elevated uric acid levels (Gonzalez-Sanchez and colleagues, 2005). Weight loss appears to raise levels of adiponectin, allowing for improved insulin sensitivity and lowered levels of inflammation. It can be predicted that the higher the baseline CRP level, the greater the rise in adiponectin levels associated with weight loss (Kopp and colleagues, 2005). Through its role as an antiinflammatory agent, adiponectin improves insulin sensitivity and lipid levels. Ghrelin is a peptide hormone that promotes appetite and is primarily produced by the stomach. Another hormone that promotes satiety is cholecystokinin, and higher amounts are noted in response to protein intake (Bowen, Noakes, and Clifton, 2006). This may be part of the reason that a higher protein intake helps regulate hunger. Adequate intake of dietary fat also is needed to promote cholecystokinin production. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), an adrenal steroid, is known to decrease body fat and appears to play a role against insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. It has been suggested that the positive effects of DHEA may be a result of stimulation of adiponectin secretion from adipose tissue (Karbowska and Kochan, 2005). Consultation with a physician is advised with regard to use of DHEA. MSG added to a typical diet for rats increased their food intake, resulting in increased levels of glucose, triglycerides, and insulin. In this study, however, rats that were fed a high-fiber diet along with the added MSG continued to have a normal intake of food (Diniz and colleagues, 2005). It can be deduced from this that MSG apparently causes an increased appetite, which can be at least partly normalized with high-fiber foods and exercise. The β-blocker propranolol was shown in a large dose to decrease resting metabolic rate (RMR) by 60 to 80 kcal/day. This reduced RMR appeared related to decreased levels of norepinephrine—a hormone that increases heart rate and is involved with sympathetic neuron functions (Monroe and colleagues, 2001). Subdermal implantable contraceptives have caused weight gain in some women. A single-rod subdermal contraceptive caused a weight increase in over 3% of women studied by Funk and colleagues (2005). Promoting healthy food choices and regular physical activity should begin in childhood. The greatest contributing factor in determining kcalorie intake by preschool children was found to be the amount of food served at meals. Parents and caretakers of children need to avoid providing excess amounts of foods to preschoolers in order to help stem the epidemic of childhood obesity (Mrdjenovic and Levitsky, 2005). Another study by the same researchers found that the greater the intake of sugar-based beverages, the greater the weight gain in children. A higher intake of sweet beverages also tended to reduce intake of milk from children’s diets (Mrdjenovic and Levitsky, 2003). The promotion of increased physical activity is of special importance to children. It is a positive strategy to stabilize weight gain and further promotes bone growth and a sense of well-being. School-based programs can be of help. A national intervention trial (Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health [CATCH]) aimed at prevention of obesity found that a structured program of physical activity and offerings of healthy foods at the elementary level helped prevent Hispanic children from gaining excess weight. Among the girls studied, the intervention group gained only 2% over a 2-year period versus 13% in a control group without the intervention, and the boys gained 1% versus 9%, respectively (Coleman and colleagues, 2005). These strategies, once started in childhood, can continue into adulthood. If the adult has learned to like a variety of plant-based, high-fiber foods and sugar-free drinks such as water, obesity is less likely to occur as caloric requirements decrease from having a sedentary job or being incapacitated from illness or from aging. It is often too late to start this process after obesity has already set in. Box 6-1 outlines the Surgeon General’s Priorities for Action in order to address the epidemic of obesity.

Obesity and Healthy Weight Management

INTRODUCTION

WHAT ARE SOME HEALTH PROBLEMS FOUND WITH OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY?

WHAT STANDARDS ARE USED TO DETERMINE WEIGHT GOALS?

to 1 lb per week is more likely to be permanent and therefore falls within the boundaries of healthy weight management. Although this may not seem like a lot of weight to lose, 1 lb per week is over 50 lb yearly. A 25- to 50-lb annual weight loss is far more likely to be a permanent weight loss than the often promoted and advertised 100 lb or more with various commercial diets.

to 1 lb per week is more likely to be permanent and therefore falls within the boundaries of healthy weight management. Although this may not seem like a lot of weight to lose, 1 lb per week is over 50 lb yearly. A 25- to 50-lb annual weight loss is far more likely to be a permanent weight loss than the often promoted and advertised 100 lb or more with various commercial diets.

OTHER BODY FAT MEASUREMENTS

WHAT ARE THE RATES OF OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY?

WHAT ARE THE KNOWN CAUSES AND THEORIES OF OBESITY?

KCALORIE IMBALANCE

TYPE OF ACTIVITY

kcal/hr*

Sedentary Activities

0-100

Reading, writing, eating, watching TV or movies, listening to radio, sewing, playing cards; typing, office work, and other activities done while sitting that require little or no arm movement or that require moderate arm movement; and activities done while sitting that require more vigorous arm movement

Light Activities

110-160

Preparing and cooking food, doing dishes, dusting, handwashing small articles of clothing, ironing, walking slowly, personal care, miscellaneous office work and other activities done while standing that require some arm movement, and rapid typing and other activities done while sitting that are more strenuous

Moderate Activities

170-240

Making beds, mopping and scrubbing, sweeping, light polishing and waxing, laundering by machine, light gardening and carpentry work, walking moderately fast, other activities done while standing

Vigorous Activities

250-350

Heavy scrubbing and waxing, handwashing large articles of clothing, hanging out clothes, stripping beds, other heavy work, walking fast, bowling, golfing, gardening

Strenuous Activities

350 or more

Swimming, playing tennis, running, bicycling, dancing, skiing, playing football

DIET QUALITY AND COMPOSITION

EATING HABITS

GENDER DIFFERENCES

ALTERED METABOLISM

HORMONAL IMBALANCES

OTHER POTENTIAL CAUSES OF OBESITY

Monosodium Glutamate

Medications

WHAT ARE SOME PREVENTION STRATEGIES FOR OBESITY?

cup potato equals the carbohydrate content of 1 slice of bread at 15 g carbohydrates—see also

cup potato equals the carbohydrate content of 1 slice of bread at 15 g carbohydrates—see also

cup of pure sugar, or about 400 kcal. This level of kcalories is expected to cause a weight gain of almost 1 lb per week if in excess of the individual’s needs. Parents and other caregivers should promote water or seltzer water as a beverage, with a maximum of 1 cup of fruit juice and 3 to 4 cups of milk daily. Soft drink intake should generally be discouraged among children. The 2005 Dietary Guidelines promote reduced intake of sweetened beverages. Childhood weight gain involves many issues. It is paramount to have the child maintain positive self-esteem and feel empowered to make appropriate food choices. Parents can assist by promoting vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and other high-fiber foods such as legumes to promote satiety while facilitating appropriate growth and development of the young child. Lean meats and use of unsaturated fats as found in nuts and peanut butter may be of further help to control hunger and limit caloric intake. Limiting the availability of foods high in saturated fat and sugar within the home can be helpful. This helps to avoid food battles by removing the stimulus.

cup of pure sugar, or about 400 kcal. This level of kcalories is expected to cause a weight gain of almost 1 lb per week if in excess of the individual’s needs. Parents and other caregivers should promote water or seltzer water as a beverage, with a maximum of 1 cup of fruit juice and 3 to 4 cups of milk daily. Soft drink intake should generally be discouraged among children. The 2005 Dietary Guidelines promote reduced intake of sweetened beverages. Childhood weight gain involves many issues. It is paramount to have the child maintain positive self-esteem and feel empowered to make appropriate food choices. Parents can assist by promoting vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and other high-fiber foods such as legumes to promote satiety while facilitating appropriate growth and development of the young child. Lean meats and use of unsaturated fats as found in nuts and peanut butter may be of further help to control hunger and limit caloric intake. Limiting the availability of foods high in saturated fat and sugar within the home can be helpful. This helps to avoid food battles by removing the stimulus.