Sigfried Oberndorfer in 1936 in Istanbul

When Sigfried was 9 years old, he probably did not think that he would discover a very specific type of malignant tumor, which even today, i.e., more than 100 years after his finding, is a strange, different, and difficult-to-treat variant of the neuroendocrine tumors (NET) [1, 2].

Sigfried was born in June 1879 in Munich, Germany. His father Heinrich and mother Helene were both Jewish. Sigfried had five siblings. The health issues of his childhood were typical of the time, centered around infectious diseases and general survival. He himself survived typhoid fever at 3 years of age, but lost a sister who at the age of 25 died of ruptured appendicitis. Sigfried was probably a skilled pupil at school, interested in Greek and Latin literature. He graduated in 1895 at 16 years of age. He proceeded to medical school at the University of Munich. He presented his thesis about syphilis in 1899, and shortly after received his medical license in 1900. Already during medical school, he became interested in pathology , which he studied in Kiel with Professor Heller, and later after finishing medical school, at the Institute of Pathology in Geneva with Professor Zahn, and in Munich with Professor Bollinger. However, he also saw living patients while working as a ship doctor on the Atlantic in 1901. To maintain a normal life and support his family, he also worked as a general practitioner for a short while. Otherwise, his main interest was pathology and he made a significant career locally, presenting research data on many topics including chronic appendicitis which also was his habilitation thesis [3]. Around this time, he met a woman named Gutta who became his wife in 1906. They later raised three children (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Sigfried Oberndorfer and his daughter Helena in Munich 1911. (From [17]. Reprinted with permission from Springer)

He was the youngest Jewish physician ever appointed to the faculty in 1906. He received, at 29 years of age, Venia Legendi (permission to teach). His inaugural lecture was a fascinating discourse about tuberculosis in the female genital organs. Later, in 1908, he was asked to organize a new pathological institute. His successful career continued, and in 1911 he was promoted to professor of pathology and became the director of the Munich-Schwabing Hospital’s Pathological Institute. Between 1911 and 1933, he continued to study medicine and pathology in his position as professor of pathological anatomy, with a break during the First World War when he volunteered and served as an army pathologist at the Western Front. The birth of his third child took Sigfried home to Munich, which probably saved him from being captured by the Allied forces, which won the Battle of Selle in 1918.

Sigfried was scientifically highly productive, releasing 333 publications encompassing an impressively wide variety of diagnoses [4–9]. He was also recognized for his educational skills, by in 1928 receiving an honorary award from the University of Munich.

Over the years, he collected a number of autopsy and pathological specimens for which a particularly strange tumor of the small intestine became his deep, personal interest. When investigating these tumors under the microscope, he noted the cancer-like appearance, and the term karzinoid was coined. His early studies immediately took him to Dresden in September 1907 where he presented his findings—karzinoide—at the annual German Pathological Society convention (Fig. 2). A paper regarding the same finding was published in the Frankfurt Journal of Pathology in December 1907. In it he described six small intestinal tumors which all grew very slowly without signs of metastases. He had gathered information about these tumors over many years, finding the first two from his time with Professor Zahn in Geneva in 1901, and another four from Professor Bollinger in Munich in 1904. For decades, this report was falsely cited as a report of a “benign carcinoma”, partly due to Sigfried’s statement that they were benign, without a tendency toward infiltration. Thus, in his initial report he happened to find cases which were amenable to surgical resection. Additionally, as a pathologist, he found them at autopsy in patients who were fairly young and who died of other causes. Sigfried worked in an era where the attention was focused around tuberculosis, infectious diseases, and death of other causes rather than cancer. However, his findings have become quite important in the modern era.

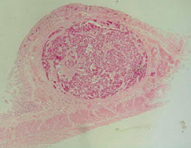

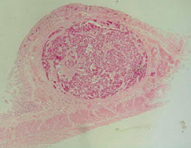

Fig. 2

Original section of Oberndorfer demonstrating a primary ileal neuroendocrine tumor. According to [17] provided by Robert Rössle (1876–1956) who was a colleague of Oberndorfer at the University of Munich. (From [17]. Reprinted with permission from Springer)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree