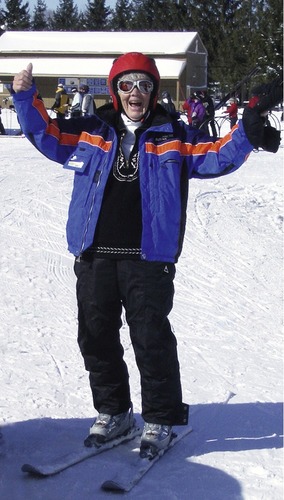

After completing this chapter, you should be able to: • Explain how social, economic, and physiologic changes affect nutritional status over the adult life span. • Discuss nutrient needs over the adult life span. • Discuss common nutrition-related medical problems of the older adult. Goals of health over the life span may differ somewhat, but one element of commonality is how to delay the aging process. Current research suggests avoiding excess kilocalories for the goal of maintaining a stable, lean body weight, avoiding saturated fat, and emphasizing high-fiber foods are key components of healthy aging (the process of getting older, which is influenced by genetics and environmental factors). A healthy lifestyle during adulthood that follows one beginning in utero can best optimize one’s genetic potential for longevity (Everitt and colleagues, 2006). Many of today’s older adults are very different from those of past generations. It has been said that 50 is the new 30, and for many 50-year-olds, being labeled “middle-aged” does not have the same connotation as it once did. Increasingly, older adults are working far past the traditional retirement age of 65 years. Older adults in their 60s and 70s may even be more physically fit than in their younger years because they have increased time for physical activity (Figure 13-1). Other, relatively young adults may already be frail and in poor health because of chronic health problems or a lifetime of poor nutritional intake and substance abuse. College is a time of weight gain for many students, especially freshman year. A variety of factors play into this, including the “all-you-can-eat” dining halls, late-night snacking (Figure 13-2), convenience of high-fat snack foods, drinking sugar-based beverages, refrigerators in dorm rooms, eating quickly, and reduced physical activity from sitting in classes along with studying in the library. The freshman 10 (pounds) has increased over time to the freshman 15, and many college students gain far more weight than this. Other changes occur to transform eating habits, from living on one’s own to eating at restaurants on dates and blending food preferences in a marriage or partnership. Social occasions contribute to overeating high-fat, high-sugar foods, some of which are entrenched in society (Figure 13-3). Becoming parents can dramatically affect mealtimes (e.g., contending with a crying baby during dinner). Various changes incurred during the early adult years will influence food habits. This includes food availability at college and work settings, new relationships with blending of food preferences, and marriage status. A study of married individuals found widowed men and women were at the greatest risk of low carotenoid levels (Stimpson and Lackan, 2007). Even the empty nest can alter food habits for older couples. Older adults may stop cooking after children leave home, or increased intake may result because of an inability to decrease amounts of food prepared. Elder adults who are cared for by an adult son or daughter may have their usual intake altered with fewer choices available. Loss of mobility to shop for food occurs when physical impairments make driving a car or using public transportation difficult. Isolation from others will result unless there are friends or family members on whom the elder person can rely. Entering a nursing home profoundly changes eating habits. It is human nature not to deal well with change. Any change in the social environment can trigger depression, which can lead to overeating or undereating with concomitant changes in weight and nutritional status. Alcohol plays a role in many adult lives. In college, binge drinking is common. One study found almost one quarter of college student current drinkers reported mixing alcohol with energy drinks. The combination of caffeine in the energy drinks with the alcohol can further impair judgment (O’Brien and colleagues, 2008). Older adults lose their ability to metabolize alcohol as efficiently as when they were younger, leading to alcohol-related problems such as falls. Caffeine plays a central role in most adults’ lives. The older adult is most likely to drink black coffee or tea, whereas young to middle-age adults have designer coffees or caffeinated soft drinks and the younger adults may eat coffee beans or consume energy drinks that are marketed to this population. Most are not drinking the caffeinated beverages intentionally as a fluid source, although they do contribute fluid for bodily needs. A study of consumers of energy drinks found two thirds drank one container due to lack of sleep or energy provided, whereas about half drank three or more with alcohol while partying. About one out of five consumers of energy drinks reported they caused headaches and heart palpitations (Malinauskas and colleagues, 2007). Once the growth spurt of adolescence is past, the need for kcalories decreases. During the aging process the basal metabolic rate begins to slow during the early adult years. By the middle adult years the amount of lean body mass (muscle tissue) begins to reduce. Exercise needs to be part of daily activities and will help to maintain muscle strength and tone throughout the adult years. Even bedridden older adults can exercise (Figure 13-4). During the later years, perceptual changes may affect eating behavior. Taste may be altered because of a decrease in the number of taste buds that occurs either as part of the aging process or as an effect of disease states, nutritional deficiencies, or medications. A reduced ability to detect odors and impaired hearing and sight may reduce the enjoyment of the social aspects of eating. All these perceptual changes may contribute to reduced food consumption. Reduced senses also increase the risk of food poisoning for the older adult who has impaired vision, taste, and smell (see Chapter 14 for guidelines on food safety). Decreases in body secretions also occur with the older adult. For example, swallowing may become more difficult because of decreased saliva production, and protein digestion is less efficient because of decreased hydrochloric acid secretion. The body’s production of digestive enzymes decreases with aging as well. Table 13-1 summarizes the effect of the physiologic changes in the older adult. Table 13-1 Physiologic Changes in the Older Adult Even though little is known about an elder person’s nutritional needs, meals should be planned according to the five-food-group system of the MyPyramid Food Guidance System, as discussed in Chapter 1. Six small meals per day are often more appropriate than three full-size meals for someone with a small appetite. Younger adults typically require 2000 to 2500 kcal daily. For this reason, the Daily Values found on food labels list the amounts of fat, carbohydrate, and protein based on these levels (see Figure 1-4). There is, however, a wide range in caloric needs for individuals, based on body composition, level of physical activity, age, and metabolism. For any adult, generally a minimum of 1200 to 1500 kcal is required to have an adequate nutritional intake, and most young adults will lose weight at these levels. For athletic adults the minimum kcalorie needs are generally at least 2000 kcal. With aging there is loss in both muscle mass and strength. This is called sarcopenia. There is some evidence that protein intake, especially from animal sources, may help reduce the risk of sarcopenia (Lord and colleagues, 2007). Milk, with its high protein content, has been found to promote increased muscle mass, especially along with resistance exercise (Wilkinson and colleagues, 2007). The Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) for vitamins and minerals are similar in older and younger adults. Eating a healthy, well-balanced diet continues its importance throughout the life span. Women living in the community who have higher serum selenium and carotenoid levels are at a lower risk of death (Ray and colleagues, 2006). On the other hand, low serum micronutrient (carotenoids, vitamins E and D) levels have been shown to increase the risk for frailty in older women. The more micronutrient deficiencies, the greater the risk of frailty (Semba and colleagues, 2006). Maintaining adequate intake of foods high in folate is important throughout the life span for its role in cell division and protein metabolism. Folate is important to help prevent cardiovascular disease in individuals who have hyperhomocysteinemia (see Chapter 7). Maintaining appropriate intake of calcium and vitamin D from the diet alone can be a challenge for a variety of reasons such as allergies or dislike of milk. Generally 1200 mg calcium and 400 International Units of vitamin D (1 mcg of vitamin D equals 40 International Units) is required daily for most adults (see differences as noted in the DRIs at the back of the book). For persons who can drink 1 quart (4 cups) of vitamin D–fortified milk, this will provide the recommended 1200 mg of calcium and 400 International Units of vitamin D. Equivalent amounts of cheese and yogurt will provide calcium but are generally low in vitamin D. As previously reviewed, a higher intake of vitamin D may be advisable in areas with limited sunshine such as in Northern areas of the world. Adults with limited sunshine, such as those who remain indoors, are advised to take increased amounts of vitamin D. A supplement of 800 International Units of vitamin D per day in combination with calcium has been shown to reduce the risk of falls and fractures (Mosekilde, 2005). Others have recommended up to 1000 International Units of vitamin D in the elder years, in conjunction with a healthy diet that provides a variety of vitamins and minerals for optimal bone health (Nieves, 2005). Total calcium and vitamin intake needs to be considered by health care professionals before supplementation is advised. Serum vitamin D levels (25[OH]D—see Chapter 3) can be monitored. The nutrient needs of the elder population over 80 years of age are not as well known. The DRI guidelines currently provide only for greater than 70 years (see the back of the book). Identification of possible unique needs of the elder population will be determined through further research. Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) occurs the first few days before the onset of the monthly menstrual cycle and disappears after menstruation. A high intake of calcium (1300 mg) and vitamin D (700 International Units) may reduce the risk of PMS (Bertone-Johnson and colleagues, 2005). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is the more severe and disabling form of PMS. This condition is estimated to occur in 2% to 9% of menstruating women. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants, used either continuously or only during the luteal phase, lead to rapid improvement in symptoms and functioning (Freeman and Sondheimer, 2003). Migraine incidence is similar between the sexes before puberty and after age 50 with the onset of menopause. About one out of four women of reproductive age experience migraines, three times the incidence of males (Raña-Martínez, 2008). Pregnancy allows for temporary cessation of menstrual migraines. Menstrual migraine attacks are more severe, of longer duration (potentially lasting more than 3 days), and are typically difficult to treat (Pringsheim, Davenport, and Dodick, 2008). Triptan medications, in particular sumatriptan, are the most effective in the management of acute menstrual migraine attack (Allais and Benedetto, 2004). See section below for dietary factors in the prevention of migraine. Although the pathogenesis of menstrual-related pain conditions is not fully understood, menstrual-related overproduction of prostaglandins is implicated in the pathophysiology of both menstrual migraine and dysmenorrhea (Mannix, 2008). Menopause is the permanent cessation of ovarian activity. Women have symptoms of menopause for a number of years before complete onset. This period is referred to as perimenopause, or the time around menopause. These symptoms can consist of weight gain, mood swings, increased serum cholesterol levels, and hot flashes. The physical changes associated with hot flashes consist of increased peripheral blood flow with a feeling of heat that is not registered as body temperature, increased heart rate, and profuse sweating. It is believed this is a disturbance of the temperature-regulating mechanism found in the hypothalamus. Asian women have lower incidence of hot flashes, which has been thought to be due to higher intake of soy products and their natural phytoestrogen content. However, dietary supplementation with phytoestrogens has not provided the same effect as hormone replacement therapy (Sturdee, 2008). Consuming soy products, rather than supplements, may be of benefit. Questions of safety and efficacy continue with herbal products. Black cohosh has been reported to be useful in the treatment of menopausal symptoms; however, the research on this herb is limited. Adverse events such as nausea, vomiting, headaches, dizziness, breast pain, and weight gain have been observed in clinical trials. A few cases of hepatotoxicity have been reported, but a direct link has not been made with black cohosh. Black cohosh does not appear to act like estrogen, a concern for women at risk for estrogen-dependent breast cancer (Mahady, 2005). Because there are few studies on the impact of herbs for control of hot flashes, and the supplement industry is largely unregulated, herbs cannot yet be widely recommended. Because women may seek their own alternatives, health professionals need to be aware of possible side effects from over-the-counter herbal products. Increasingly, adults of all ages are engaging in sports (see Figure 13-1). There are a variety of reasons from simple pleasure to body building or health reasons. There are many positive reasons to maintain a high level of physical activity throughout the adult life span. In regard to decreasing insulin resistance to help manage diabetes, it has been observed that high-intensity exercise is more effective than moderate intensity. With the equivalent of 1000 kcal per week of high-intensity exercise, insulin sensitivity and metabolism of glucose increased 20% (Coker and colleagues, 2006). Aerobic and resistance exercise have been found to be comparable in improving glucose metabolism in older men (Ferrara and colleagues, 2006). In helping to maintain muscle mass in older ages, a higher level of physical activity also is needed. Leisure type activities were found to be insufficient in preventing sarcopenia in persons greater than 65 years of age (Raguso and colleagues, 2006). Minimizing inflammatory conditions among older adults also appears necessary to minimize loss of muscle strength (Schaap and colleagues, 2006). Adequate protein intake is further important, with some evidence that older adults require a higher intake of protein beyond the DRI of 0.8 g/kg of body weight to maintain muscle mass. Goals for protein need to be evaluated in terms of preexisting renal or liver disease that precludes an increased intake. For the health professional working with athletes, understanding the fundamental nutritional needs and interventions is essential. Being able to help prevent and correctly identify the cause of exercise-induced problems is paramount in preventing physical injury or mortality of athletes. Resistance training is not without potential harm. It is associated with periods of acute intracellular hypoxia (lack of oxygen within the body cells ) and low intramuscular pH levels. Rhabdomyolysis (a condition resulting from muscle injury with release of cell contents into the plasma) can be caused by overly aggressive resistance training such as excessive weight lifting. Excess physical tension on the muscle fibers and lowered levels of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) with altered electrolyte levels in the cell can induce this condition. Symptoms of rhabdomyolysis include muscle soreness, reduction in the range of motion, decreased muscle strength, black urine, and, in severe cases, acute renal failure. A gradual training program with maintenance of appropriate hydration is advised to prevent this condition (Heled and colleagues, 2005). Most adults easily meet their protein requirements. With adequate kcalorie intake, protein needs are only slightly increased for low- to moderate-intensity endurance at an estimated 1.0 g of protein per kilogram of body weight. Results suggest that a protein intake of 1.2 g/kg or 10% of total energy intake is needed to achieve a positive nitrogen balance for higher levels of physical activity. This is not a concern for most endurance athletes who routinely consume protein at or above this level (Gaine and colleagues, 2006). For the elite athlete the maximum protein requirement has been estimated at 1.6 g/kg of body weight (Tarnopolsky, 2004). Diet plays a role in promotion of muscle mass with adequate kcalories and protein required. Protein requirements for novice weightlifters are not elevated (Moore and colleagues, 2007). This is due to the beneficial effect of resistance training that lowers requirements for protein initially (Hartman, Moore, and Phillips, 2006). Ultimately, increased dietary protein intake (up to 1.6 g of protein per kilogram of body weight daily) may best promote increased muscle development in response to resistance exercise. Adequate protein and kcalories is particularly important for the elder population in this quest (Evans, 2004). Including milk after resistance exercise has been shown to improve the body’s uptake of amino acids needed in muscle protein production. Evidence suggests whole milk may be more efficient at protein synthesis than low-fat milk (Elliot and colleagues, 2006). The benefit of milk may be more important in groups of persons with low levels of lean mass and strength such as the elderly (Phillips, Hartman, and Wilkinson, 2005). Healthy young men who routinely include milk after exercise were shown to have greater muscle growth during early stages of resistance training when compared with soy or carbohydrate sources (Hartman and colleagues, 2007). The optimal amount of the milk proteins, casein and whey, has been observed at 40 g/day of whey protein plus 8 g/day of casein for the greatest increase in lean tissue development (Kerksick and colleagues, 2006). Young adults generally do not need supplemental protein sources beyond that provided by diet to increase lean tissue mass and strength (Candow and colleagues, 2006).

Nutrition Over the Adult Life Span

INTRODUCTION

WHAT ARE NUTRITIONAL CONCERNS OF THE YOUNG ADULT?

HOW DO LIFE CYCLE ISSUES AFFECT NUTRITIONAL STATUS?

SOCIAL CHANGES

PHYSICAL CHANGES

COMPONENT

FUNCTIONAL CHANGE

OUTCOME

Body composition

↓ Muscle mass

↑ Fat tissue in muscle size and strength

↓ Basal metabolic rate

↓ Caloric requirements

↓ Bone density

↑ Risk of osteoporosis

Perceptions

↓ Hearing

Feeling of isolation

Slowing of adaptation to darkness

Reluctance to eat in public places or at large social affairs

Need for brighter light to perform tasks

↓ Number of taste buds

↓ Ability to taste salt, sweet

↑ Ability to taste bitter and sour

Gastrointestinal tract

↓ Smell

↑ Threshold for odors

↓ Motility

Constipation

↓ Hydrochloric acid

↓ Efficiency of protein digestion

More prone to food poisoning

↓ Saliva production

Difficulty swallowing

Heart

↑ Blood pressure

↓ Ability to handle physical work and stress

Lungs

↓ Ability to use oxygen

↑ Fatigue

↓ Capacity to oxygenate blood

↓ Capacity for exercise

Endocrine

↓ Number of secretory cells

↓ Blood hormone levels

↓ Insulin production

↑ Blood glucose level

Kidney

↓ Renal blood flow

↓ Capacity for filtration and absorption

WHAT ARE THE NUTRIENT NEEDS OVER THE LIFE SPAN?

ENERGY

PROTEIN

VITAMINS AND MINERALS

WHAT ARE SOME NUTRITION ISSUES FOR WOMEN?

PREMENSTRUAL SYNDROME

MENSTRUAL MIGRAINES

MENOPAUSE

WHAT ARE NUTRITIONAL NEEDS FOR PHYSICAL ENDURANCE, STRENGTH, AND HEALTH IN SPORTS AND PHYSICALLY DEMANDING OCCUPATIONS?

SPORTS NUTRITION ISSUES

PROTEIN NEEDS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine