Nutrition in Pregnancy and Lactation

1 University of California, Irvine, CA

2 Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, PA

3 City College of New York, New York, NY

Introduction

While adequate nutrition is important throughout the lifespan, it is especially crucial for pregnant and lactating women, whose nutrient and energy demands substantially increase in order to provide for the needs of their fetus and infant. By understanding the changes in nutritional requirements throughout pregnancy and during lactation, healthcare providers can make informed recommendations regarding diet alterations and supplementation.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that maternal nutrition not only affects the health and development of the newborn, but also the subsequent health of the growing child, even into adulthood. Avoiding nutritional deficiencies during pregnancy promotes optimal outcomes for both mother and baby; avoiding nutritional deficiencies during lactation promotes prolonged breastfeeding, maternal health and satisfaction, and optimal infant development.

Metabolic and Physiologic Consequences of Pregnancy

The physiological and biochemical changes that occur during pregnancy have evolved to accommodate and promote the growth and development of the fetus. These changes include the development and growth of the feto-placental unit, increased maternal blood volume, increased maternal adipose tissue, decreased gastrointestinal (GI) motility, and breast enlargement to prepare for lactation. Throughout pregnancy, hormonal alterations create maternal insulin resistance and increase the uptake of fatty acids in extra-uterine tissues, both of which promote the transport of glucose to the developing fetus. In order to support the additional energy requirements of her developing fetus, a woman must adjust her daily caloric intake throughout pregnancy. The increased requirements depend upon pre-conception body mass index (BMI), maternal developmental stage (adolescence versus adulthood), and the gestational age of the pregnancy. Additionally, because the developing fetus depends entirely on maternal dietary consumption to support nutritional and metabolic needs, it is crucial that a pregnant woman increases her intake of various nutrients to ensure that her own resources are not depleted and that fetal requirements are adequately met.

Integrating Nutrition into the Obstetric History

Ideally, every woman should meet with a healthcare provider for a pre-pregnancy physical examination and nutritional assessment; however, according to the March of Dimes, half of pregnancies are unplanned. A major objective of the healthcare team is to collect sufficient information to evaluate the pregnant woman’s nutritional status and identify risk factors for the pregnancy. For each pregnant patient, a detailed obstetric history should be reviewed, because the outcomes of previous pregnancies have implications for the current pregnancy. This history should include the total number and dates of prior pregnancies, maternal and fetal outcomes, and any previous complications, including: low birth-weight infant (<2500 g; <5 pounds 8 ounces), macrosomia or high birth-weight infant (>4000 g; >8 pounds 13 ounces), or small or large for gestational age infant (<10th or >90th percentile for gestational age).

Weight-gain patterns during previous pregnancies, prior history of nausea, vomiting, or hyperemesis during pregnancy, gestational diabetes, eclampsia, anemia, pica, current and previous weight (BMI), and patterns of contraception use should also be determined. Previous breastfeeding experience should be assessed, as well as the woman’s planned breastfeeding preference.

The medical history should also identify maternal risk factors for nutritional deficiencies and chronic diseases with nutritional implications (e.g., absorption disorders, eating disorders, metabolic disorders, infections, diabetes mellitus, phenylketonuria (PKU), sickle cell trait, or renal disease). Woman who have had a short pregnancy interval (i.e., less than a year between pregnancies) are at increased risk of having depleted nutrient reserves. Maternal nutrient depletion may be associated with an increased incidence of pre-term birth, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and maternal morbidity/mortality. Caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drug consumption should be quantified in the medical history, as should any vitamin or herbal supplementation or alternative pharmacological therapies. A history of medication use should also be obtained to evaluate the extent to which past or present medications may affect nutrient absorption.

In addition to the medical history, questions regarding professional, social, economic, and emotional stresses and specific religious practices (including dietary restrictions and fasting) should be included to account for any possible effects on the patient’s nutritional status. Some work environments adversely impact dietary intake, as they may not provide adequate time to eat or allow access to only nutritionally marginal food. For this reason, pregnant patients should be asked about the conditions of their employment, and limitations and potential solutions should be discussed. For women of lower socioeconomic status, it is important to inquire about access to nutritious food and the ability to store and prepare food, and referral to food assistance programs may be appropriate (e.g., Women, Infants and Children – WIC).

Nutrition Assessment in Pregnancy

The purpose of a nutrition assessment is to identify women with nutritional risk factors that could jeopardize their health or the health of their fetus. A thorough evaluation of a woman’s nutritional status prior to or during pregnancy includes clinical, dietary, and laboratory components. Both patient interviews and written questionnaires are appropriate for gathering information about current and past dietary practices. Pertinent dietary information includes appetite, meal patterns, dieting regimens, cultural or religious dietary practices, vegetarianism, food allergies, and cravings and/or aversions. Information about abnormal eating practices, such as following food fads, bingeing, purging, laxative or diuretic use, or pica (eating non-food items such as ice, detergent, starch, chalk, clay, or rocks) is essential. Other relevant information includes the habitual use of caffeine-containing beverages (more than 200 mg/day), sugar substitutes and other special “diet” foods, vitamins, minerals, and herbal supplements. Use of dietary supplements may not be volunteered and their use should be elicited as they may be inappropriate or dangerous during pregnancy. A woman’s current dietary practice can be assessed using the 24-hour recall, usual intake, or food frequency questionnaire discussed in Chapter 1.

Some women are receptive to nutrition counseling just prior to or during pregnancy, making this an opportune time to encourage the development of good nutritional and physical activity practices aimed at preventing future medical problems such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and osteoporosis. Pregnant and lactating women found to have nutritional risk factors may benefit from a referral to a registered dietitian (See Table 3-1).

Table 3-1 Medical Conditions Where Consultation with a Registered Dietitian is Advisable

Source: Lisa Hark, PhD, RD. 2014. Used with permission.

|

Physical Examination

An essential part of the clinical evaluation is assessing pre-pregnancy weight for height by calculating the BMI or using BMI tables (Figure 1-1). The BMI is used to evaluate weight status and should be explained to the patient to help her set appropriate weight-gain goals. Whenever possible, pre-pregnancy weight should be ascertained from clinical records obtained just prior to pregnancy. Current weight should be measured and rate of weight gain assessed at each visit.

Maternal Weight-Gain Recommendations

Maternal weight gain is attributable both to increases in the mother’s tissue (increased circulating blood volume, breast mass, uterine size) and feto-placental growth within the uterus (increased size of the fetus, placenta, and amniotic fluid volume). During the first half of gestation, weight gain primarily reflects changes in maternal stores and fluid status. In the second half of gestation, weight gain is the result of continued maternal accumulation, as well as fetal growth. Rapid weight gain near the end of gestation, after approximately 32 weeks, usually represents the increase in tissue edema.

The rate of weight gain during pregnancy is important because maternal weight gain and infant birth weight are correlated. Most weight gain should occur in the second and early third trimesters (18 to 30 weeks). Adequate weight gain in the second trimester of pregnancy seems to be predictive of fetal and neonatal weight, even if weight gain is inadequate during the remainder of the pregnancy.

The Institute of Medicine recommendations (Table 3-2) state that women with low pre-pregnancy BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) should increase their caloric intake substantially to attain a weight gain between 28 and 40 pounds during the course of pregnancy. Women with normal pre-pregnancy BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) should increase their caloric intake moderately to gain between 25 and 35 pounds during the course of pregnancy, and overweight women with high BMI (25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2) should increase their caloric intake in a more limited fashion, with a goal of a 15- to 25-pound weight gain during the course of pregnancy. An area of controversy is the weight gain needs of obese women. Women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 are considered obese and should gain as little as 11 to 20 pounds during the pregnancy. For twin pregnancies, the Institute of Medicine recommends a gestational weight gain of 37 to 54 pounds for women of normal weight, 31 to 50 pounds for overweight women, and 25 to 42 pounds for obese women. Data are insufficient to determine the optimal weight gain for women with triplet and higher order gestations.

Table 3-2 Recommended Weight Gain During Pregnancy

Source: Recommended Weight Gain During Pregnancy. Institute of Medicine.

| BMI | Weight Gain (kg) | Weight Gain (lb) |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight BMI < 18.5 | 12.7–18.2 | 28–40 |

| Normal weight BMI 18.5–24.9 | 11.4–15.9 | 25–35 |

| Overweight BMI 25–29.9 | 6.8–11.4 | 15–25 |

| Obese | ||

| BMI > 30.0 | 6.8 | 15 |

| Twin gestation | 15.9–20.4 | 35–45 |

Low Pre-conception BMI (underweight)

Women with low pre-conception BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) are at risk for delivering low-birth-weight infants. If a woman who was underweight before conception does not gain adequate weight during her pregnancy, these risks are increased. As with general nutritional assessment and treatment, the optimal time for evaluating and treating underweight women is prior to conception; however, this is often an unrealistic option. A woman with a BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2 who is considering pregnancy should be encouraged to gain weight before conceiving. If an underweight woman has conceived without gaining adequate weight, she should be encouraged to gain between 28 and 40 pounds over the course of her pregnancy. Protein–calorie supplementation may assist in correcting preconception nutritional deficits and provide adequate nutrients for fetal development.

Inadequate weight gain (<2 lb/month during the second and third trimesters) is associated with low-birth-weight infants, IUGR, and fetal complications. Inhibited fetal growth usually correlates with inadequate weight gain. Signs of IUGR include a discrepancy between gestational age and uterine size or fetal biparietal diameter measured by ultrasonography. Women with inadequate weight gain or weight loss should have repeated and thorough nutritional evaluations. Careful diet histories should be taken to determine the adequacy of dietary intake, supplementation should be provided as necessary, and referral to a registered dietitian is recommended.

Overweight and Obesity

Women with a high preconception BMI (>26 kg/m2) are at risk for developing gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational hypertension, thromboembolic events, preeclampsia, and for delivering macrosomic infants (>4000 g or 8 pounds 13 ounces). Additionally, the rate of cesarean delivery increases with an increasing BMI.

To avoid inadequate intake of crucial nutritional components, which can adversely affect both mother and fetus, pregnant women with a high pre-conception BMI should limit their weight gain during the course of their pregnancies. However, they should not severely restrict their caloric intake such that the nutrients required to sustain a healthy pregnancy are insufficient. Although there is considerable controversy regarding the management of pregnancy in obese women, the current guidelines call for limited maternal weight gain. Despite the presence of pre-conception obesity, severe caloric restriction during pregnancy should not be considered, as caloric restriction is linked to inadequate intake of important macro- and micronutrients. Even in severe obesity, carbohydrate recommendations are 175 g/day. Adequate consumption of calcium, iron, folate, B vitamins, and protein are particularly crucial during pregnancy, regardless of maternal weight. If caloric intake is inadequate, ingested proteins are catabolized for energy needs and are thus unavailable for maternal/fetal protein synthesis. An estimated 32 kcal/kg per day is necessary for optimal use of ingested protein. Severe restriction of caloric intake, paired with severe restriction of carbohydrate intake, can result in ketosis, which in studies of diabetic women has been shown to be detrimental for the developing fetus. Ketone bodies are concentrated in amniotic fluid and absorbed by the developing fetus. Studies have also suggested an association between ketosis and reduced uterine blood flow. The mental development of children whose mothers have had ketonuria during pregnancy has been shown to be stunted, although the direct causal link between fetal ketosis and inhibited mental development has yet to be definitively established.

Rapid, excessive weight accumulation is usually the result of fluid retention, which may indicate development of preeclampsia. Fluid retention in the absence of hypertension or proteinuria is not an indication for salt restriction or diuretic therapy, but women who retain fluid should be monitored for other signs of preeclampsia. Edema in the lower extremities is caused by the accumulation of interstitial fluid secondary to the obstruction of the pelvic veins that commonly occurs during the later stages of pregnancy. Edema can be treated by elevating the legs and wearing support hose.

Slow excessive weight accumulation during pregnancy may be caused by fat deposition. As excessive weight gain is associated with both maternal and fetal morbidities; weight gain that exceeds the recommendations appropriate for pre-conception BMI should be monitored. A careful dietary history should be taken to determine the source of excess weight gain and recommendations for dietary changes should be offered accordingly.

Adolescence

It is helpful for the healthcare team to stress the importance of good, life-long nutritional habits, as well as the nutritional changes necessary for optimal pregnancy outcomes. Young adolescents, in particular, may still be growing and may need to gain additional weight to accommodate normal growth during the 40 weeks of the average gestation.

The pattern of weight gain, as well as the total weight gain during pregnancy, has been shown to be particularly important in adolescent women. Inadequate weight gain prior to 24 weeks, even if total pregnancy weight gain is adequate, is associated with low-birth-weight deliveries in the adolescent population. Pregnant adolescents should strive for weight gain patterns similar to those recommended for women with low pre-pregnancy BMI. Adolescents need to fulfill the nutritional requirements of their own continued growth and development as well as the energy requirements of their developing fetuses. However, adolescents are more likely to consume diets that are low in micronutrients, such as iron, zinc, folate, calcium, and vitamins A, B6, and C, and higher in energy from macronutrients including total fat, saturated fat, and sugar.

Recent research on adolescents suggests that the macronutrient components of the diet are also important determinants of birth weight. Adolescents whose diets are higher in total carbohydrates seem to have lower overall risk of delivering a low-birth-weight baby or having a pre-term delivery compared to adolescents with diets lower in carbohydrates.

Laboratory Evaluation

Routine tests related to the nutritional status of pregnant women should be performed at the beginning of pregnancy and again during the second trimester. Screening for anemia by checking hemoglobin and hematocrit is recommended in the first trimester and again at 24 to 28 weeks. When these measures are low, iron stores should be assessed with serum ferritin and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) levels. The clinician must be aware of ethnic or racial differences when interpreting these laboratory studies. For example, African–American women tend to have higher levels of ferritin than Caucasian women. Patients of African–American, Southeast Asian, and Mediterranean descent are also at increased risk for having sickle cell disease, sickle cell trait, and/or thalassemia. They should be evaluated for these inherited disorders if their initial screen shows anemia in the presence of normal iron stores. Screening for gestational diabetes using a 1-hour glucose tolerance test should be done in all patients at 24 to 28 weeks gestation. Urinary screening for the presence of glucose and protein, as a screen for diabetes and renal disease, respectively, should be conducted at every visit.

Maternal Nutrient Needs: Current Recommendations

Energy and Protein

The total maternal energy requirement for a full-term pregnancy is estimated at 80,000 calories. Basal requirements can be determined based on maternal age, stature, activity level, pre-conception, BMI, and weight gain goals. During the first trimester, total energy expenditure does not change greatly and weight gain is minimal; therefore, additional energy intake is recommended only in the second and third trimesters. An additional 340 kcal/day is recommended during the second trimester and 452 kcal/day during the third trimester. Additional protein is needed during pregnancy for fetal, placental, and maternal tissue development. Protein recommendations are therefore increased from 46 g/day for an adult, non-pregnant woman to 71 g/day during all trimesters.

Vitamin and Mineral Supplementation Guidelines

Routine vitamin/mineral supplementation for women reporting appropriate dietary intake and demonstrating adequate weight gain (without edema) is not mandatory. However, most healthcare providers prescribe a prenatal vitamin and mineral supplement because many women do not consume an adequate diet to meet their increased nutritional needs during the first trimester of pregnancy, especially with regard to folic acid.

Folic Acid

Folic acid deficiency is the most common vitamin deficiency during pregnancy, and insufficient levels of folic acid are known to cause neural tube defects (NTDs) in the fetus. NTDs include defects in the formation of the fetal skull, scalp, brain tissue, spinal cord, and vertebrae. For decades, the association between low levels of folic acid and fetal NTDs has been understood. In addition, medications known to interfere with folate metabolism such as diphenylhydantoin, aminopterin, or carbamazepine cause fetal NTDs. In 1991, the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study Research Group published a study that demonstrated women with a history of a NTD in a prior pregnancy who took 4 mg of folic acid per day before pregnancy and through the 12th week of gestation experienced a 72 percent reduction in their recurrence risk of NTD. In 1992, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that all women of childbearing age take 400 µg/day of supplemental folic acid, in order to ensure adequate levels of folate are present when pregnancy occurs, whether intended or not. Because neural tube development and closure is complete by 18 to 26 days after conception, the neural tube is nearly formed by the time a woman misses her period and becomes aware she is pregnant. Thus, it is especially crucial that women planning to become pregnant consume adequate folic acid before pregnancy, and continue their supplementation during the first four weeks of pregnancy. The RDA for folate in women of childbearing age is currently 400 µg/day, and for pregnant women is 600 µg/day. Women with a history of NTD should be advised to consume 4 mg (400 µg) per day of folic acid.

Typically, the diet in the United States has lacked folate-rich food sources and patients might have been deficient in folate. For this reason, the government began a folic acid fortification program in 1997. Grain products, such as cereals, pastas, rice, and breads, are now fortified with folic acid. Good dietary sources of natural folate include dark green leafy vegetables, green beans and lima beans, orange juice, fortified cereals, yeast, mushrooms, pork, liver, and kidneys. (See Appendix F: Food Sources of Folate.)

Dietary folate is dramatically influenced by food storage and preparation; for instance, it is destroyed by boiling or canning. Folate stores are likely to be easily depleted among women who are of lower socioeconomic status, have folate-deficient diets, or are alcoholics. Additionally, evidence exists to suggest that the long-term use of oral contraceptives inhibits folate absorption and enhances folate degradation in the liver. Therefore, folate stores may be more rapidly depleted in women who have used oral contraceptives, which may lead to a higher incidence of folate deficiency in such women if they become pregnant.

Choline

While not essential because it is present in many foods and can be synthesized by the liver, choline is a popular supplement for pregnant women. Research studies in animals and a limited number of human trials have demonstrated reduced risk of NTDs with choline supplementation but an active area of interest is the possibility of reduced risk factors for schizophrenia and increased IQ.

Calcium

Calcium is needed for fetal skeletal development. Additionally, evidence has shown that calcium supplementation reduces the risk of developing gestational hypertension. Over the course of pregnancy, a single fetus requires between 25 and 30 g of calcium, which represents only 2.5 percent of total maternal stores. In the first half of pregnancy, calcium requirement is just an additional 50 mg/day above the 1000 mg/day required for non-pregnant women. Most of the additional calcium requirement during pregnancy occurs during the third trimester, during which the fetus absorbs an average of 300 mg/day. In contrast to maternal iron and folate stores, which are relatively small and therefore easily depleted, maternal calcium stores are large and are mostly stored skeletally, allowing for easy mobilization as needed.

The RDA for calcium in women aged 9 to 19 is 1300 mg/day, and in women aged 19 to 50, the RDA is 1000 mg/day. Obtaining adequate intake of dietary calcium presents no problem for women who consume at least three servings of dairy foods every day. Women who limit their intake of dairy foods because of lactose intolerance can often satisfy their daily calcium requirement by eating yogurt, cheese, calcium-rich vegetables, and products fortified with calcium, such as soymilk, orange juice, cereal, and bread. (See Appendices G and H: Food Sources of Calcium.)

If increased intake is not possible or effective, supplementation may be needed. Calcium carbonate, gluconate, lactate, or citrate may provide 500 to 600 mg/day of calcium to account for the difference between the amount of calcium required and that consumed. The tolerable upper intake for calcium during pregnancy is 2500 mg/day. The standard prenatal vitamin contains 250 mg. Multivitamins marketed to the non-pregnant population generally have less than 200 mg/serving. Calcium is thought to be absorbed in doses up to 600 mg at one time, making it unlikely that pregnant women would reach the upper tolerable limit.

Iron

Iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of maternal and infant death, pre-term delivery, and low-birth-weight babies; and has negative consequences for normal infant brain development and function. The prevalence of prenatal iron deficiency is higher in African–American women, low-income women, teenagers, women with less than a high-school education, and women who have had more than two prior pregnancies. Healthy People 2020 goals include reducing anemia among pregnant females in their third trimester from 29 to 20 percent and reducing ethnic and income disparities. WIC Programs have been successful in reducing the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy and postpartum.

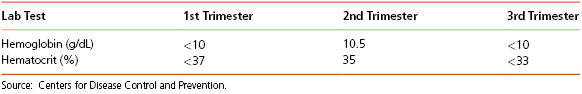

According to the CDC, screening for anemia should take place prior to pregnancy, as well as during the first, second, and third trimesters in high-risk individuals. The diagnosis of anemia by trimester is shown in Table 3-3. Since hemoglobin levels normally decline during pregnancy due to the significant increase in maternal blood volume, ferritin and MCV should be measured as diagnostic criteria, since these values remain constant. A serum ferritin level of less than 15 ng/mL warrants aggressive treatment and may require parental iron rather than oral supplementation.

Table 3-3 Diagnosis of Anemia in Pregnancy

A total iron increase of over 1000 mg is required during pregnancy. Maternal blood volume increases throughout pregnancy by 30 percent, and this increased erythropoeisis requires an additional 450 mg of iron to be delivered to the maternal marrow. The fetus and the placenta require 350 mg of iron, and approximately 250 mg of iron is lost in blood during delivery. It is difficult for many women to meet the iron requirements of pregnancy by diet alone. Healthcare providers generally recommend iron supplementation as a daily supplement of 30 mg of elemental iron in the form of simple salts, beginning around the twelfth week of pregnancy for women who have normal pre-conception hemoglobin measurements.

The RDA for iron is 27 mg/day in pregnancy and 9 mg/day for lactating women. For women who are pregnant with multiple fetuses or those with low pre-conception hemoglobin measurements, a supplement between 60 and 100 mg/day of elemental iron is recommended until hemoglobin concentrations are normal. After normalization, iron supplementation of 27 mg/day should be continued. There are various forms of ferrous salts on the market, each containing a different amount of elemental iron:

- ferrous fumarate: 106 mg elemental iron/tablet,

- ferrous sulfate: 65 mg elemental iron/tablet,

- ferrous gluconate: 28 to 36 mg iron/tablet.

Iron supplementation can have gastrointestinal side effects such as constipation, therefore a stool softener or natural laxative should be prescribed with the iron supplement. Because the degree of gastrointestinal side effects directly correlates with the amount of elemental iron ingested, changing to a lower-dose of elemental iron is very effective. For example, if a patient cannot tolerate a tablet of ferrous sulfate (containing 65 mg elemental iron), changing to ferrous gluconate (containing 28 mg elemental iron) or iron bis-glycinate (Ferrochel, Gentle Iron) (containing 27 mg elemental iron) can be effective. Because iron is best absorbed in an acidic medium, iron can be taken with a 250 mg ascorbic acid tablet or a half-glass of orange juice for optimal absorption. If a patient is also taking antacids for gastro-esophageal reflux disease, advise the patient that iron and antacids should not be taken concurrently. (See Appendix L: Food Sources of Iron.)

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin obtained largely from consuming fortified milk or juice, fish oils, and dietary supplements. It also is produced in the skin with exposure to sunlight. Vitamin D that is ingested or produced in the skin must undergo hydroxylation in the liver to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], then further hydroxylation primarily in the kidney to the physiologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. This active form supports absorption of calcium from the gut and enables normal bone mineralization and growth. During pregnancy, severe maternal vitamin D deficiency has been associated with skeletal anomalies, fractures, and congenital rickets. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy occurs commonly in certain high-risk groups, including vegetarians, women with limited sun exposure (e.g., those who reside in northern latitudes) and in women with darker skin. Although there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening all pregnant women for vitamin D deficiency, maternal serum 25(OH)D levels can be measured in women at high risk for deficiency. Although there is no consensus on an optimal serum 25(OH)D level in pregnancy, most agree that a serum level of at least 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) is needed to avoid bone loss. When vitamin D deficiency is identified during pregnancy, 1000 to 2000 international units (IU) per day of vitamin D3 is recommended. (See Appendix B: Food Sources of Vitamin D.)

Vitamin A

The RDA for vitamin A is 770 µg/day in pregnancy and 1300 µg/day during lactation. Severe vitamin A deficiency is rare in the United States and an adequate intake of vitamin A is readily available in a healthy diet. Women with lower socioeconomic status, however, may consume diets with inadequate amounts of vitamin A. Increasing dietary intake of vitamin A is possible and should be encouraged in lieu of supplementation to avoid excessive intake, which has been reported to be teratogenic, leading to spontaneous abortions and fetal malformations including microcephaly and cardiac anomalies. A safe upper limit for vitamin A intake during pregnancy has been recognized at 3000 µg/day. Over-the-counter multivitamin supplements may contain excessive doses of vitamin A and thus should be discontinued during pregnancy. Additionally, topical creams that contain retinol derivatives commonly used to treat acne should be discontinued during pregnancy and in women trying to become pregnant.

Omega 3 Fatty Acids

N-3 Fatty acids are another popular supplement used by many pregnant women, specifically docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). Some research studies have demonstrated higher IQ in babies born to supplemented mothers. Practitioners might encourage fish oil supplements in their patients who don’t consume fish.

Dietary Fiber

There are no specific recommendations for dietary fiber intake during pregnancy; however, increased intake of high-fiber foods, such as vegetables, whole grains, and fruit, is recommended for the prevention and treatment of constipation. Constipation is a common complication of pregnancy due to hormonal changes because progesterone produced in pregnancy relaxes smooth muscle in the colon and decreases peristalsis. Emphasizing adequate fluid intake is important when increasing dietary fiber. (See Appendix O: Food Sources of Dietary Fiber.)

Fluids

Pregnancy represents a unique state where circulating blood volume increases by 50 percent. Tissue fluid also increases, while blood pressure decreases in the second trimester and then returns to pre-pregnant levels near term. The dynamic changes of blood volume and blood pressure during pregnancy require substantial fluid intake in order to maintain blood flow to vital organs. Inadequate fluid intake is associated with premature uterine contractions, pre-term delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. General recommendations are to drink at least 64 ounces (1920 mL) of water per day. In areas where the water supply is suspected to contain lead, women should be encouraged to drink bottled water. Excessive lead intake may result in spontaneous abortion, decreased stature, and impaired neuro-cognitive development of the baby.

Food Contamination

Food contaminated by contact with heavy metals or pathogenic bacteria can produce devastating effects on the developing fetus, as most heavy metals are considered teratogenic. In particular, case reports of teratogenicity or embryotoxicity have been reported involving methyl mercury, lead, cadmium, nickel, and selenium. In addition, heavy metals can have neurotoxic effects on the fetus. Mercury can be removed from vegetables by peeling or washing well with soap and water. Consumption of raw fish products and highly carnivorous fish (including tuna, shark, tilefish, swordfish, and mackerel) should be limited or avoided during pregnancy. All foods should be handled in an appropriately sanitary manner to prevent bacterial contamination. All dairy foods and juices consumed during pregnancy should be pasteurized.

Listeria monocytogenes contamination results in food poisoning during and outside of pregnancy. In pregnancy, however, listeriosis can develop into a blood-borne, transplacental infection that can cause chorioamnionitis, premature labor, spontaneous abortion, or fetal demise. To avoid listeriosis, pregnant women should wash vegetables and fruits, cook meats, and avoid processed, pre-cooked meats (cold cuts) and raw cheeses (brie, blue cheese, Camembert, and Mexican caso-blanco).

Alcohol

Alcohol is a known teratogen. Excessive consumption of alcohol by pregnant women can result in fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) which manifests in such fetal deformities as microcephaly, cleft palate, and micrognathia. Heavy alcohol consumption during pregnancy is also associated with low neonatal weight, and deficiencies in B vitamins and protein. Maternal alcoholism contributes to fetal nutritional deficiencies because it inhibits maternal absorption of nutrients, and increases nutrient losses (e.g., zinc).

While it is certain that heavy maternal drinking is harmful to developing fetuses, the issue of whether a modest amount of alcohol consumption is acceptable during pregnancy remains controversial. There is no known safe level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy; therefore, it is currently recommended that alcohol intake be avoided by pregnant women and women attempting to become pregnant. According to the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, no amount of alcohol consumption can be considered safe during pregnancy. Alcohol should be avoided entirely throughout the first trimester. Although the debate remains as to whether mild-to-moderate drinking affects fetal development in the latter trimesters of pregnancy, the Council on Scientific Affairs of the American Medical Association also recommends abstinence from alcohol throughout pregnancy. The CDC recommends that clinicians identify women at risk in the preconception period and provide education and support for cessation of alcohol use.

Cigarette Smoking

Nicotine consumption during pregnancy has been consistently associated with low neonatal weight. If women who smoke become pregnant, they should be advised to discontinue cigarette use for the sake of their fetuses.

Caffeine

According to the March of Dimes, women who are pregnant or trying to become pregnant should limit their caffeine intake to no more than 200 mg/day, which is equivalent to about two 8-ounce cups of brewed coffee. During the first trimester, excessive caffeine intake is shown to increase the risk of spontaneous abortion (miscarriage). The United States Food and Drug Administration recommend that pregnant women reduce their intake of caffeine from all sources. Since caffeine is present in teas, hot cocoa, chocolate, energy drinks, coffee ice-cream, and soda, it is best to advise decaffeinated beverages for women who are pregnant or trying to become pregnant.

Exercise during Pregnancy

Many studies support the benefits of moderate exercise in women whose pregnancies are considered low risk. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, most pregnant women should participate in 30 minutes or more of moderate exercise on most, if not all, days. Safe activities include walking, swimming, dancing, and yoga. Regular physical activity improves posture, promotes muscle tone, strength, endurance, energy level, and mood, while reducing constipation, backache, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and varicose veins. It may help reduce the risk of diabetes and high blood pressure during pregnancy and help women recover faster after delivery.

Pregnant women should be advised to avoid contact sports and any activities that can cause even mild trauma to the abdomen, such as ice hockey, kickboxing, soccer, and basketball, as well as activities with a high risk for falling, such as gymnastics, horseback riding, downhill skiing, vigorous racquet sports, and scuba diving. They should be advised to drink plenty of fluids before, during, and after exercise and avoid hot tubs, saunas, and jacuzzis. Warning signs to stop exercising include vaginal bleeding, uterine contractions, decreased fetal movement, fluid leaking from the vagina, dizziness or feeling faint, increased shortness of breath, chest pain, headache, muscle weakness, and calf pain or swelling.

Common Nutrition-related Problems during Pregnancy

Discomforts of pregnancy such as nausea and vomiting, constipation, and heartburn may generally be improved by implementation of the guidelines summarized here.

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting seem to be associated with increased levels of the pregnancy hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), which doubles every 48 hours in early pregnancy and peaks at about 12 weeks gestation. Nausea is experienced by 60 percent of pregnant women and, of these, only a small percent require hospitalization for severe hyperemesis gravidarum.

Heartburn and Indigestion

Heartburn and indigestion are usually caused by gastric content reflux that results from both lower esophageal pressure and decreased motility. Limited gastric capacity, secondary to a shift of organs to accommodate the growing fetus, contributes to these symptoms in the third trimester of pregnancy. Strategies for managing heartburn or indigestion are the same as those suggested for managing nausea and shown in Table 3-4.

Table 3-4 Strategies for Managing Nausea, Vomiting, Heartburn, and Indigestion in Pregnancy

Source: Lisa Hark, PhD, RD. 2014. Used with permission.

|

Constipation

Constipation during pregnancy is associated with an increase in water reabsorption from the large intestine. In addition, smooth muscle relaxation with resultant slower gastrointestinal tract motility occurs during pregnancy. The pregnant woman often notes overall gastrointestinal discomfort, a bloated sensation, an increase in hemorrhoids and heartburn, and decreased appetite. Strategies for managing constipation during pregnancy are shown in Table 3-5.

Table 3-5 Strategies for Managing Constipation in Pregnancy

Source: Lisa Hark, PhD, RD. 2014. Used with permission.

|

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree