7 Nutrition and Lifestyle

Introduction

In an interesting study published in 2005, patients with cancer (including over 450 patients with breast cancer) were asked why they thought they had developed cancer.1 Researchers concluded that respondents typically underestimated the importance of behavioral factors that are known to be associated with increased cancer risk, such as obesity and physical inactivity, while overestimating the importance of stress and environmental pollution. The authors stressed that patient education, particularly regarding modifiable risk factors, is paramount. This chapter aims to educate the clinician to be able to educate the patient about which potentially modifiable nutrition and lifestyle factors do or do not place her at increased risk of breast cancer.

Over the last two decades, possible associations among nutrition, lifestyle, and cancer risk have garnered more public attention and press. In 2007, an international committee of experts (World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research [WCRF/AICR]) provided a summary of scientific evidence on the effect of nutrition on cancer up to the mid-1980s. The report estimated that up to one third of cancer incidence worldwide was preventable by healthy eating, weight control, and appropriate physical activity.2 Studies of families in Scandinavian countries have suggested that environmental factors may be responsible for up to 80% of breast cancer risk.3 Also supporting the association between environmental factors and risk of cancer is the fact that rates of breast cancer vary tremendously from country to country, and areas with similar lifestyles (e.g., North America and Western Europe) tend to have similar rates of breast cancer. Furthermore, when women emigrate from a country with a low rate of breast cancer to a country with higher breast cancer incidence, the immigrant’s risk of breast cancer rises to mirror that of her adopted country.4 Moreover, risk continues to rise for second and later generations of immigrants.

Diet

Fruit and Vegetable Intake

Based on a review of data published through the mid-1980s, the 2007 WCRF/AICR report2 concluded that a high consumption of fruits and vegetables probably decreases the risk of breast cancer. Studies analyzed since that time have not been as definitive, however.5 In general, retrospective studies are more likely to show an association, whereas prospective studies are not likely to show such an association. For example, in 2001, Smith-Warner and associates6 pooled data from eight prospective cohort studies and found no evidence of a protective effect for fruit and vegetable intake. The study group chose to analyze cohort studies rather than case-control studies to minimize effects of recall bias and included only studies with at least 200 cases as well as excellent dietary recording/analysis techniques. Studies included not only overall fruit and vegetable intake but also specific groups of fruits and vegetables and individual food items. The pooled studies included 7377 incident invasive breast cancer cases occurring among 351,825 women whose diets were analyzed at baseline. In addition to not finding associations between overall fruit and vegetable intake and breast cancer, subanalysis did not find such associations for green leafy vegetables, 8 botanical groups, or 17 specific fruits and vegetables.

Highlighting the idea that case-control studies likely overestimate associations owing to recall bias, a meta-analysis published in 2003 found a slight protective effect of fruit and vegetable intake in 15 case-control studies but no association in 10 prospective cohort studies.7

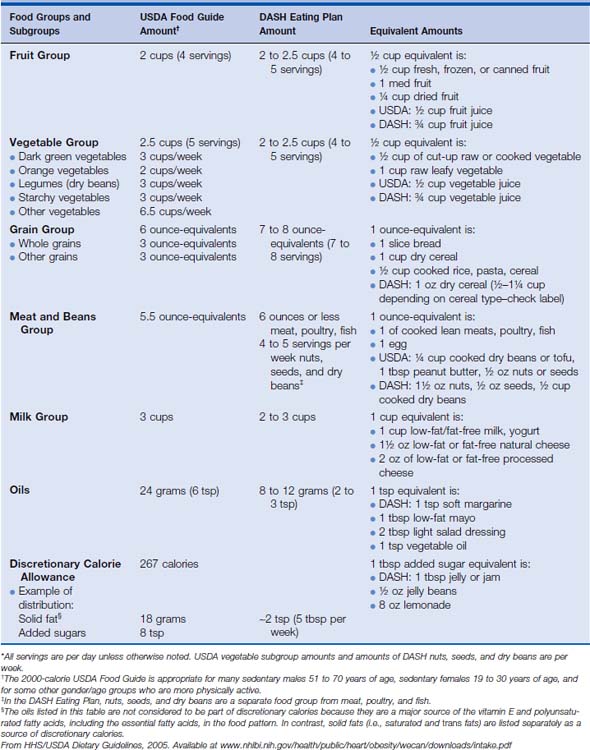

A large prospective study, the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), followed up 285,526 women between ages 25 and 70 years who were recruited from eight European countries. Participants completed a dietary questionnaire at enrollment (1992-1998) and were followed up for development of cancer until 2002 (mean follow-up 5.4 years). The authors acknowledge that the study period thus far is short, but so far associations between fruit or vegetable intake and breast cancer risk have not been seen.8 Nevertheless, maintaining a healthy lifestyle includes eating a good balance of various foods each day. Sample recommended diets are shown in Table 7-1.

Table 7-1 Sample USDA Food Guide and the DASH Eating Plan at the 2000-Calorie Level* (Amounts of various food groups that are recommended each day or each week in the USDA Food Guide and in the DASH Eating Plan (amounts are daily unless otherwise specified) at the 2000-calorie level. Also identified are equivalent amounts for different food choices in each group. To follow either eating pattern, food choices over time should provide these amounts of food from each group on average.)

Glycemic Load

The glycemic index is a value given to specific foods to enable comparison of the relative impact that ingesting each food will have on blood glucose level. Foods with a high glycemic index raise the blood glucose proportionally higher than foods with a lower glycemic index (Table 7-2). It has been theorized that high consumption of foods with a high glycemic index may predispose to the development of cancer because cells with a high metabolic activity are preferential users of glucose. Also, foods with a high glycemic index may contribute to higher insulin levels; insulin has been shown to act as a growth factor and perhaps promotes tumor growth. Epidemiologic studies have shown a very small but statistically significant link between diabetes and risk of breast cancer; patients with type 2 diabetes show elevated blood glucose and insulin levels.9

Table 7-2 Glycemic Index by Glycemic Load

| Low GI | Medium GI | High GI |

|---|---|---|

| Low GL | ||

| Medium GL | ||

| High GL | ||

First number in parentheses is glycemic load, second is glycemic index.

GL: Low = 1–10, Med = 11–19, High = 20+

GI: Low = 1–55, Med = 56–69, High = 70–100

Available at: www.mendosa.com/common_foods.htm

From Revised International Table of Glycemic Index (GI) and Glycemic Load (GL). Am J Clin Nutrition July 2002.

One relatively large cohort study compared women with breast cancer with age-matched women without breast cancer and interviewed all subjects about intake of foods with a high glycemic index. The study enrolled 2569 women with breast cancer; controls were 2588 hospitalized women with unrelated conditions. Compared with women with the lowest intake and adjusting for other risk factors (age, body mass index [BMI], total calorie intake), women with the highest intake of desserts or sugars had multivariate odds ratio [OR] of 1.19 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02-1.39).10

Saturated Fat

Animal studies have shown saturated fat to be a promoter of mammary carcinogenesis, controlling for total caloric intake. In addition, in many studies high dietary fat intake has been linked to higher serum levels of estradiol.11

Some epidemiologic studies have linked fat intake to an increased incidence of breast cancer, but again case-control and prospective cohort studies have yielded conflicting results. In 2003, Boyd and associates4 combined case-control with cohort studies examining this relationship and estimated a 19% overall increased risk of breast cancer for the highest versus the lowest levels of saturated fat intake. However, when these studies were separated and analyzed according to study types, neither an analysis of the case-control studies nor an analysis of the cohort studies was able to show a significant correlation.4

The Women’s Health Initiative study, best known for concluding that routine use of postmenopausal hormonal replacement therapy is unwarranted, also investigated the intervention of a low-fat diet on the risk of development of breast cancer.12 Over 48,800 women ages 50 to 79 at the start of the trial were put on a low-fat diet (with an aim of 20% of calories from fat) or were asked to continue their regular diet. The group assigned to the low-fat diet lowered their fat intake to 24% by the end of the first year, but this number rose to 29% by the end of the sixth year. Still, this was much less than the approximately 37% fat diet that both groups began with and that the normal diet group continued with. There was no statistically significant difference in development of breast cancer between the two groups, although there was a trend toward benefit. A 9% decrease in risk of breast cancer was seen for the low-fat group, but it was not statistically significant. It is interesting that there was a suggestion of a dose-response relationship, since women who had the highest fat intake at the start of the study and who reduced fat intake the most saw the greatest reduction in risk.

Decreasing dietary fat intake may have more of a benefit in prevention of secondary breast cancer. The Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study randomized 2437 women with early-stage, treated breast cancer in a prospective manner to a dietary intervention group (n = 975) or control group (n = 1462).13 Women in the treatment group lowered their mean daily fat intake at 12 months to 33.3 g compared with 51.3 g in the control group. The intervention group also had a statistically significant mean 6-pound weight loss during the study period. After a median 5 years of follow-up, local, regional, distant, or ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence or new contralateral breast cancer had been reported in 9.8% of women in the dietary intervention group and in 12.4% of women in the control group, giving a statistically significant 0.76 relative risk (RR) of recurrence for the intervention group.13

Dairy Products

Eating low-fat dairy products may protect a woman from developing breast cancer, although the reasons this is so are not well elucidated. A prospective observational study, the Nurses– Health Study, followed up over 88,000 pre- and postmenopausal women and recorded dietary information at time of enrollment (1980) and every 4 years until the study’s completion in 1994.14 For premenopausal women, the study found an inverse association between breast cancer risk and intake of low-fat dairy products, calcium (owing mainly to dairy intake rather than supplement use), vitamin D (owing mainly to supplement use and not dairy intake), and lactose. The risk reduction comparing highest (>1 serving/day) and lowest ≤3 servings/month) intake categories were 0.68 (95% CI 0.55-0.86) for low-fat dairy foods and 0.72 (95% CI 0.56-0.91) for skim or low-fat milk. Risk reduction was also seen with dairy calcium (>800 mg/day versus ≤200 mg/day; RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.48-0.98), total vitamin D (>500 IU/day versus ≤150 IU/day; RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.55-0.94), and lactose (quintile 5 versus quintile 1; RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.54-0.86). No association was seen for any of these dietary factors with postmenopausal breast cancer risk, however.14

A nutrition cohort was begun in 1992 as a subset of a population followed up by the American Cancer Society, in which the Cancer Prevention Study II did find an inverse relationship between dietary calcium and breast cancer for postmenopausal women.15 Over 68,500 postmenopausal women completed a dietary survey after enrollment (1992-1993) and were surveyed in 2001 for breast cancer status. Data were controlled for weight gain, hormone replacement therapy use, and other lifestyle factors. Analysis showed that women who consumed the most dietary calcium (>1250 mg/day) had a 20% lower risk of postmenopausal breast cancer compared with those in the lowest category of intake (<500 mg/day; RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.67-0.95; ptrend 0.02), but supplemental calcium did not change this risk. Neither dietary vitamin D intake nor supplementation with vitamin D was associated with decreased risk of breast cancer development overall, although the development of estrogen receptor-positive tumors was lower in the group with the most vitamin D intake (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.59-0.93; ptrend 0.006).15

Soy Foods

Biologic Plausibility

Perhaps the most controversial area of nutrition is defining the relation of soy foods to risk of breast cancer development and growth. Soy foods are among the most potent food sources of isoflavones, compounds that are chemically very similar to estrogens. This fact, along with the epidemiologic data showing that Asian women, with a much higher per-capita consumption of soy foods, have a lower incidence of breast cancer than do women who do not eat an Asian diet, has intrigued scientists. A conference (sponsored by the soy industry) was convened in 2005 to review research on the subject of soy and breast cancer risk.16 Researchers noted that soy isoflavones have been shown in some in vitro and animal studies to stimulate growth of breast cancer cell lines, yet isoflavones, by a nonhormonal mechanism, have also been shown to inhibit tumor growth.

Observational Studies

A case-control study of breast cancer among Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino women in Los Angeles County quantified intake of soy during adolescence and adult life. Controlling for other risks for breast cancer, researchers interviewed 501 breast cancer patients and 594 control subjects. The authors described a significant inverse association between soy intake during adolescence and adult life and the development of breast cancer, with consumption of soy during adolescence appearing to confer the greatest reduction in risk. They found that women who reported soy intake at least once per week during adolescence showed a statistically significant reduced risk of breast cancer. There was also a significant trend of decreasing risk with increasing soy intake during adult life. Subjects who were high soy consumers during both adolescence and adulthood showed the lowest risk (OR 0. 53, 95% CI 0.36-0.78) compared with those who were low consumers during both periods of their lives.17

A larger case-control study of non-Asian Americans, also in California and during the same time period, did not find an association between phytoestrogen consumption and breast cancer risk. Interviews were conducted with 1326 subjects and 1657 controls. Usual intake of specific phytoestrogenic compounds was assessed via a food frequency questionnaire and a nutrient database. In this study, phytoestrogen intake was not associated with breast cancer risk (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.80, 1.3 for the highest versus lowest quartile). Subgroup analysis did not differ.18

A meta-analysis of 18 studies from 1978 to 2004 concluded that intake of soy may have a small protective effect against development of breast cancer, but the study urged caution in interpreting the results since the studies did not show a dose-response pattern and most had significant methodologic issues as well. Among all women, high soy intake was modestly associated with reduced breast cancer risk (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75-0.99).19

Fish Consumption

Omega-3 fatty acids have been noted in vitro and in animal studies to inhibit breast cancer cell growth, but case-control and cohort epidemiologic studies matching dietary fish intake–the biggest dietary source of omega-3 fatty acids–with breast cancer risk have yielded inconsistent results. As part of the EPIC study, 310,671 women between 25 and 70 years old completed a dietary survey at enrollment and then were followed up for an average of 6.4 years for the development of breast cancer. Though criticized for the short follow-up period, this study showed no association between fish intake and cancer development.20

Vitamins, Minerals, and Other Supplements

Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid)

Vitamin C is a strong antioxidant that provides reducing potential for biochemical reactions, especially those using iron or copper. Vitamin C is of interest in cancer prevention because it theoretically blocks or prevents some processes that may lead to carcinogenesis. Although epidemiologic reviews show increased cancer in vitamin C-deficient populations and animals, controlled trials of supplementation for cancer prevention have failed to show a definitive link. Vitamin C is a water-soluble vitamin; excess intake is excreted by the kidneys and may be associated with renal stones or diarrhea. A 1990 meta-analysis of 12 case-control studies investigated the link between dietary vitamin C intake and breast cancer risk and found a statistically significant inverse relationship.21 However, further case-control studies as well as prospective studies, including some studies in which supplemental vitamin C was taken long term and at high doses, have failed to show a consistent association.22

Vitamin A and Carotenoids

Vitamin A–either from animal sources as preformed vitamin A (retinol and retinyl esters) or from plant sources as carotenoids converted into retinal–is involved with cell proliferation and differentiation, making it an attractive target of investigation in cancer research. Vitamin A has antioxidant properties as well. The Nurse’s Health Studies and other case-control studies23–25 have found inconsistent relationships between vitamin A intake and breast cancer risk. Though of short duration, the Women’s Health Study randomized, in a double-blind fashion, almost 40,000 women to beta-carotene or placebo for 2 years, with 2 more years of follow-up, and did not find a decrease in risk of breast cancer. There is some suggestion that vitamin A may be protective among smokers and that vitamin A may reduce the chance that a breast cancer is estrogen receptor-negative; however, studies are not definitive.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree