Nursing Home Care: Introduction

The focus of this chapter is the clinical care of nursing home residents. Some of the basic demographic and economic aspects of nursing home care are discussed in Chapters 2 and 15. Ethical issues relevant to nursing home care and palliative care are discussed in Chapters 17 and 18, respectively. Many older people who would have otherwise been in nursing homes are now residing in assisted living facilities or in their own homes. Management of older people with multiple medical problems and geriatric conditions in this setting is challenging. Chapter 15 and the Suggested Readings at the end of this chapter provide more information on this level of care.

The poor quality of care provided in many nursing homes has been recognized for decades (Institute of Medicine, 2000). Since the Institute of Medicine issued its critical report in 1986 (Institute of Medicine, 1986) and the mandating of the Resident Assessment Instrument in 1987, the overall quality of care has improved. More recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has instituted several changes that are designed to improve the quality of nursing home care. These include the Nursing Home Compare website (http://www.medicare.gov/nhcompare/home.asp), which shows consumers (and nursing homes) how individual homes perform on surveys and specific quality indicators; the new federal survey process employing the Quality Indicator Survey (QIS; http://www.cms.gov); the Five-Star rating system (http://www.Medicare.gov); and the new requirement in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act that all nursing homes must have a Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement (QAPI) program. Because older people who are typically in nursing homes suffer from multiple underlying diseases, good medical care is especially important. Despite the logistical, economic, and attitudinal barriers that can foster inadequate medical care in the nursing home, many straightforward principles and strategies can improve the quality of medical care for nursing home residents. Fundamental to achieving these improvements is a clear perspective on the goals of nursing home care, which differ in many respects from the goals of medical care in other settings and patient populations.

The Goals of Nursing Home Care

The modern nursing home serves multiple roles. Table 16–1 lists the key goals of nursing home care. While the prevention, identification, and treatment of chronic, subacute, and acute medical conditions are important, most of these goals focus on the functional independence, autonomy, quality of life, comfort, and dignity of the residents. Physicians and other clinicians who care for nursing home residents must consider these goals while the more traditional goals of medical care are being addressed.

|

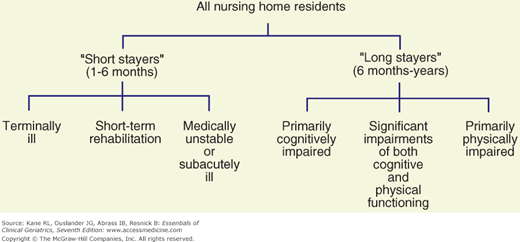

The heterogeneity of the nursing home population results in a diversity of goals for nursing home care. Nursing home residents can be subgrouped into six basic types (Fig. 16-1). While it is not always possible or desirable to isolate these different types of residents geographically, and although residents often overlap or change between the types described, subgrouping nursing home residents in this manner will help the clinician and interdisciplinary team to focus the care-planning process on the most critical and realistic goals for individual residents.

The underlying social contract implied by nursing home admission is quite different for each of these groups. In some cases, access to treatment takes precedence over the living environment; in other circumstances, the environment may be the most critical element of care. Those admitted to a nursing home with the intent of active treatment and discharge home may be willing to accept a living situation akin to that of a hospital in the expectation that the benefit they receive from treatment will offset any discomfort or inconvenience. For terminally ill persons under the hospice model, the living environment is made as flexible and supportive as possible. Efforts are directed toward making these patients comfortable and permitting them to enjoy, to the extent possible, their last days. For the other groups in the middle of this distribution, attention to both making their living situation comfortable and active primary care are important. Ideally, a nursing home should be able to provide what the name implies: active nursing (and medical care) and a homelike environment.

Clinical Aspects of Care for Nursing Home Residents

In addition to the different goals for care in the nursing home, several factors make the assessment and treatment of nursing home residents different from those in other settings (Table 16–2). Many of these factors relate to the process of care. A fundamental difference in nursing home care compared to care in other settings is that medical evaluation and treatment must be complemented by an assessment and care-planning process involving staff from multiple disciplines. The integral involvement of nurses’ aides in the development and implementation of care plans is crucial to high-quality nursing home care. Data on medical conditions and their treatment are integrated with assessments of the functional, mental, and behavioral status of the resident in order to develop a comprehensive database and individualized plan of care.

|

Several factors complicate medical evaluation and clinical decision making for nursing home residents. Unless the physician has cared for the resident before nursing home admission, it may be difficult to obtain a comprehensive medical database. Residents may be unable to relate their medical histories accurately or to describe their symptoms, and medical records are frequently unavailable or incomplete, especially for residents who have been transferred between nursing homes and acute-care hospitals. When acute changes in status occur, initial assessments are often performed by nursing home staff with limited skills and are transmitted to physicians by telephone. Even when the diagnoses are known or strongly suspected, many diagnostic and therapeutic procedures among nursing home residents are associated with an unacceptably high risk–benefit ratio. For example, an imaging study may require sedation with its attendant risks; nitrates and other cardiovascular drugs may precipitate syncope or disabling falls in frail ambulatory residents with baseline postural hypotension; and adequate control of blood sugar may be extremely difficult to achieve without a high risk for hypoglycemia among cognitively impaired diabetic residents with marginal or fluctuating nutritional intake, who may not recognize or complain of hypoglycemic symptoms.

Further compounding these difficulties is the inability of many nursing home residents to participate effectively in important decisions regarding their medical care. Their previously expressed wishes are often not known, and an appropriate or legal surrogate decision maker has often not been appointed. These issues are discussed further later in this chapter and in Chapter 17.

Table 16–3 lists the most commonly encountered clinical disorders in the nursing home population. They represent a broad spectrum of chronic medical illnesses; neurological, psychiatric, and behavioral disorders; and problems that are especially prevalent in frail older adults (eg, incontinence, falls, nutritional disorders, chronic pain syndromes). Although the incidence of iatrogenic illnesses has not been systematically studied in nursing homes, it is likely to be as high as or higher than that in acute-care hospitals. The management of many of the conditions listed in Table 16–3 is discussed in some detail in other chapters of this text.

Medical conditions Congestive heart failure Degenerative joint disease Diabetes mellitus Gastrointestinal disorders Reflux esophagitis Constipation Diarrhea Conjunctivitis Gastroenteritis Kidney disease (chronic kidney disease, renal failure) Lung disease (chronic obstructive, emphysema, asthma) Malignancies Neuropsychiatric conditions Dementia Behavioral disorders associated with dementia Wandering Agitation Aggression Depression Neurological disorders other than dementia Stroke Parkinsonism Multiple sclerosis Brain or spinal cord injury Pain: musculoskeletal conditions, neuropathies, malignancy Geriatric conditions and syndromes Delirium Incontinence Gait disturbances, instability, falls Malnutrition, feeding difficulties, dehydration Pressure sores Insomnia Functional disabilities necessitating rehabilitation Stroke Hip fracture Joint replacement Amputation Iatrogenic disorders Adverse drug reactions Falls Nosocomial infections Induced disabilities Restraints and immobility, catheters, unnecessary help with basic activities of daily living Palliative care and end-of-life care |

Process of Care in the Nursing Home

The process of care in nursing homes is strongly influenced by numerous state and federal regulations, the highly interdisciplinary nature of nursing home residents’ problems, and the training and skills of the staff that delivers most of the hands-on care. Federal rules and regulations contained in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA 1987) and implemented in 1991 place heavy emphasis on assessment and care planning as a means of achieving the highest practicable level of functioning for each resident and the use of the Resident Assessment Instrument (http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/MDS30RAIManual.html). The Minimum Data Set (MDS), recently updated to version 3.0, is the foundation of clinical assessment and care planning for individual residents. In addition to the MDS, each resident or responsible health-care agent should be assisted in articulating the goal for the patient’s nursing home care (ie, short-term rehabilitation of medical and nursing management with the goal of returning home; long-term care of chronic conditions; or palliative or hospice care). Detailed guidance for state and federal surveyors has been developed for several clinical care areas, such as unnecessary drugs and urinary incontinence. Failure to adhere to the clinical recommendations contained in the regulations and related surveyor guidance can result in citations and, in some instances, financial penalties for the nursing home. Failure to appropriately manage medical conditions in the nursing home puts the facility and physician at risk for lawsuits (Stevenson and Studdert, 2003).

Physician involvement in nursing home care and the nature of medical assessment and treatment offered to nursing home residents are often limited by logistic and economic factors. Few physicians have offices based either inside the nursing home or in close proximity to the facility. Many physicians who do visit nursing homes care for relatively small numbers of residents, often in several different facilities. Many nursing homes, therefore, have numerous physicians who make rounds once or twice per month, who are not generally present to evaluate acute changes in resident status, and who attempt to assess these changes over the telephone. Increasingly, practice patterns are shifting to a model of physician–nurse practitioner practice teams caring for large numbers of residents in several nursing homes. Such physician–nurse practitioner teams have been shown to improve care and reduce hospitalization rates (Burl et al., 1998; Reuben et al., 1999; Kane et al., 2003; Konetzka, Spector, and Limcangco, 2008). Many nursing homes do not have ready availability of laboratory, radiological, and pharmacy services with the capability of rapid response, further compounding the logistics of evaluating and treating acute changes in medical status. Thus, nursing home residents are often sent to hospital emergency rooms, where they are evaluated by personnel who are generally not familiar with their baseline status and who frequently lack training and interest in the care of frail and dependent elderly patients.

Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement policies also dictate certain patterns of nursing home care. While physicians are required to visit nursing home residents only every 30 to 60 days, many residents require more frequent evaluation and monitoring of treatment—especially with the shorter acute-care hospital stays brought about by the prospective payment system. Many of these visits can be made by a nurse practitioner or physician assistant. While Medicare reimbursement for physician visits in nursing homes has improved, reimbursement for a routine visit is sometimes inadequate for the time that is required to provide good medical care in the nursing home, including travel to and from the facility; assessment and treatment planning for residents with multiple problems; communication with members of the interdisciplinary team and the resident’s family; and proper documentation in the medical record. Activities often essential to good care in the nursing home, such as attending interdisciplinary conferences, family meetings, complex assessments of decision-making capacity, and counseling residents and surrogate decision makers on treatment plans in the event of terminal illness, are generally not reimbursable at all. Medicare intermediaries sometimes restrict reimbursement for rehabilitative services for residents not covered under Part A skilled care, thus limiting the treatment options for many residents. Although Medicaid programs vary considerably, many provide minimal coverage for ancillary services that are critical for optimum medical care and may restrict reimbursement for several types of drugs that may be especially helpful for nursing home residents.

Amid these logistic and economic constraints, expectations for the care of nursing home residents are high. Table 16–4 outlines the various types of assessment generally recommended for the optimal care of nursing home residents. Physicians are responsible for completing an initial assessment within 1 week of admission and for arranging for monthly visits thereafter for the next 90 days. More frequent visits are generally necessary for residents admitted on a Medicare Part A skilled nursing benefit. Registered nurses assess new residents as soon as they are admitted and on a daily basis, and they generally summarize the status of each resident weekly. The nationally mandated MDS must be completed within 14 days of admission and updated when a major change in status occurs; several sections must be routinely updated on a quarterly basis. The MDS is intended to assist nursing home staff in identifying important clinical problems that need further evaluation, management, and monitoring. It is also used as the basis for calculating daily reimbursement rates for residents on the Medicare Part A skilled benefit by generating a resource utilization group (RUG) that reflects case mix and needed staffing levels (a number of states also use the version of the RUGS for Medicaid payments) and as the basis for calculating various quality measures, including those on the Nursing Home Compare website and those used for the Five-Star rating system.

Type of assessment | Timing | Major objectives | Important aspects |

|---|---|---|---|

Medical initial | Within 72 h to 1 week after admission | Verify medical diagnoses Medication reconciliation Document baseline physical findings, mental and functional status, vital signs, and skin condition Attempt to identify potentially remediable, previously unrecognized medical conditions Get to know the resident and family (if this is a new resident) Establish goals for the admission and a medical treatment plan | A thorough review of medical records and physical examinations is necessary Relevant medical diagnoses and baseline findings should be clearly and concisely documented in the patient’s record Medication lists should be carefully reviewed and only essential medications continued Request for specific types of assessment and input from other disciplines should be made A database should be established (see example in Fig. 16-2) |

Periodic | Monthly or every other month | Monitor progress of active medical conditions Update medical orders Communicate with patient and nursing home staff |