Introduction

All societies that have had access to psychoactive drugs have used them. There are multiple positive aspects of psychoactive drug use, from creating positive mood states, to stress and pain relief, to increasing social bonding, to simple preservation of health (for much of human history it was safer to drink locally available wine or beer than locally available water). Psychoactive drug use also has many negative aspects, from impairing psychological and social functioning, to disinhibition and release of aggression, to inebriation and accidents, to causing infections and fatal diseases, and to fatal overdose. The potential positive and negative consequences of psychoactive drug use have led to many different social mechanisms for regulating access to and use of psychoactive drugs, from incorporating drug use into religious rituals, to informal social norms, and to civil and criminal laws.

The “Harm Reduction” framework is the most recently developed framework for regulating psychoactive drug use, and we would argue, the most appropriate framework for use in large, complex societies in which patterns of drug use, and the individual and societal adverse consequences of use can change very rapidly.

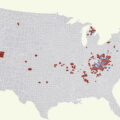

Much of harm reduction theory and practice was developed in Western Europe and Australia [ ], but as this book focuses on the current opioid epidemic in the United States, this chapter will also focus on harm reduction in the United States. There are three aspects of the US situation that have greatly influenced the course of harm reduction in this country. First is the sheer size of the psychoactive drug use in the United States. Recent estimates are that there are 6.2 million persons in the United States with illicit drug use disorders [ ]. The large size of the US drug using population creates the potential for enormous profits to be a made from importing or manufacturing illicit drugs, and from diverting drugs from medical sources. With this large demand, eliminating supply is simply not possible. Second is the great extent to which interracial and interethnic conflict has been incorporated into drug policies in the United States. A full examination of the relationships between drug use and racial/ethnic conflicts in the United States is beyond the scope of this chapter, but we would note several aspects of US culture that have been of great importance to drug use and drug policies in the country. Many of the original European colonists belonged to religious groups who held extremely negative views of drug use, considering drugs to be products of the devil and drug use to be inherently sinful [ ]. Slavery in the United States was developed in part to create very large-scale production of a psychoactive drug (nicotine in tobacco) [ ]. Prohibition of alcohol in the United States in 1918 was a product of cultural conflict between rural/small city dominated by Protestants and urban areas dominated by Catholic immigrants. The bars and saloons portrayed as dens of evil that ruined family life were in particular associated with German immigrants, and Prohibition was passed at the end of World War I. Third, the United States is a federal system, with state and local governments having great but not complete authority in the area of public health. Thus, state and local governments have often implemented harm reduction programs despite intense opposition at the federal level (for example, implementation of needle/syringe exchange programs). Many states, however, are dependent upon the federal government for the funding of their public health programs, so that opposition to harm reduction at the federal level can also be quite effective.

What harm reduction is not

There have been several attempts to define and characterize harm reduction with many common elements but without a definitive consensus [ , ]. This is not surprising given the rapid development of the framework over the last several decades. We believe that, as a starting point for understanding the current state of harm reduction in the United States, with respect to policy and direct services, it is helpful to begin with consideration of what harm reduction is not. In our assessment, there is probably more agreement on what harm reduction is not rather than on what harm reduction is (at any given historical moment).

First, harm reduction is clearly not an ethnocentric condemnation of people who use certain types of drugs. This is specifically relevant in the context of illicit versus licit drugs. Legality typically creates a framework for moral judgment about a person based on the psychoactive drugs they choose to consume (for example, the use of alcohol or cigarettes vs. heroin in the United States). Harm reduction does not make this global distinction, but rather considers individual drugs and individual routes of administration in terms of the potential harms to be addressed. As noted above, there are long traditions of drug use in many different cultures. Drug use that is new to a dominant cultural group and associated with minority groups within the society has often been moralistically condemned, with heavy criminal penalties imposed on active use and possession. Examples include the use of opium by Chinese immigrants [ , ], use of marijuana by Mexicans [ ], and, more recently, use of crack cocaine by African-Americans all in the United States [ ]. The imposition of extremely heavy penalties for possession of drugs as well as quality of life crimes often associated with dependence (panhandling, etc.) was often in the name of fear of more serious crimes associated with drug use and which incorporated overt racism. This has led to mass incarceration in the United States which has widely been condemned as racist and stands, in some ways, in opposition to how the United States has treated the recent opioid epidemic which has largely affected white, working class individuals.

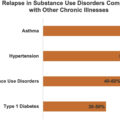

A second point is the desired outcomes of substance use treatment. Harm reduction does not insist that abstinence is the only acceptable outcome for the treatment of substance use disorders. Harm reduction includes the use of psychoactive medications during treatment. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT), particularly methadone and buprenorphine, and the use of psychiatric medications are not only acceptable components of the harm reduction approach to treatment of substance use disorders but can lead to important improvements in physical and mental health and overall quality of life [ ].

Third, harm reduction is not confined to illicit drugs. Indeed, addressing licit drug use is an increasingly important aspect of harm reduction. In recent years, with the increase in the number of people who are becoming addicted to prescription opioids, harm reduction organizations have had to expand their services and outreach methods to work with communities where the primary drug problem has become the misuse of prescription opioids.

Fourth, harm reduction does not include unlimited commercial exploitation of psychoactive drugs. With their ability to generate dependence, both licit and illicit psychoactive drugs can be extremely profitable. Harm reduction recognizes the need for limitations on the distribution and marketing of drugs. In the United States, harm reduction organizations have been some of the biggest proponents for reform of prescribing practices for opioids and stricter regulation on how pharmaceutical companies market their drugs to healthcare providers and patients [ ].

Finally, harm reduction does not expect to create a perfect world. It is not a vision of a drug-free world, in which no one uses psychoactive drugs, nor it is a vision in which everyone who uses drugs does so in a harm-free manner. Harm reduction necessarily involves trade-offs between different forms and quantities of individual and societal harms associated with the many varieties of psychoactive drug use.

Positive principles of harm reduction

The harm reduction perspective emphasizes the need to base policy on research, rather than on stereotypes of drug users, both illicit and licit users. There have been hundreds of studies of the major harm reduction interventions—MAT for opioid use disorders, syringe services programs (distribution of new syringes, cookers, cotton, smoking pipes, and other drug use paraphernalia) to reduce transmission of HIV, and antiretroviral treatment for HIV infection—and there is a strong scientific consensus that they can be very effective [ , ]. The current status of the research is that the benefits of harm reduction programs are sufficiently well established that it would be unethical to withhold these programs from a “control group” in future research. It is important to note, however, that harm reduction programs are not likely to be effective if they are poorly implemented. The programs need to treat people who use drugs with dignity and respect, and they need to be implemented on a large, public health scale.

The research has also shown that harm reduction programs do not lead to increases in illicit drug use. Indeed the US opioid epidemic, with its large increases in people who use drugs (PWUD), has been particularly severe in the areas of the county that historically have had the least amount of harm reduction services, such as Appalachia [ ].

Harm reduction incorporates a human rights approach to health. Health and healthcare are seen as basic human rights, and that all persons receiving health-related services should be treated with dignity and respect. Harm reduction aims to preserve the importance of individual rights while providing adequate treatment for persons with psychoactive drug use problems. Most importantly, harm reduction has led to a growing recognition that adverse consequences of nonmedical drug use (such as HIV transmission) can be reduced without increasing illicit drug use. It thus acts as a wholistic view of “health” and what it means to have a substance use disorder.

Harm reduction is a collaborative process, involving persons who use drugs in both policy formulation and in implementing programs (such as peer harm reduction programs). Peers can assist in providing comprehensive and accurate information on how to use drugs safely, while delivering harm reduction supplies to drug users. Peers are also often nonjudgmental, an important aspect of fostering relationships with drug users, who are often stigmatized. Further, within harm reduction, people who use drugs are seen as members of the community, and the health of the community as a whole depends upon maintaining the health of persons who use drugs.

Finally, harm reduction is constantly evolving. Patterns of drug use and the individual and societal harms change continually and often rapidly; one of the most recent changes in drug use patterns has been the recent increase in opiate and fentanyl use in the United States [ ]. Some problems associated with drug use have been reduced to minimal levels, but other problems require continuous efforts and new problems can rapidly arise. For example, combined prevention (including needle/syringe exchange programs, MAT, and antiretroviral treatment for HIV positive persons) has effectively ended the HIV epidemic among persons who inject drugs (PWID) in New York City [ ]. However, HCV incidence among PWID is still unacceptably high in New York City, approximately 19.5/100 for those injecting for 6 years or less, which will likely end up being one of the next drivers of change in harm reduction theory [ ].

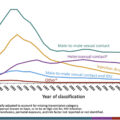

As noted throughout this book, the current opioid epidemic in the United States is the latest public health crisis associated with psychoactive drug use. Before considering how harm reduction may be applied to this current public health crisis, it will be useful to consider the back and forth between drug use epidemics, harm-increasing responses to the epidemics, and resistance to harm reduction responses to the epidemics over the last century. The following historical timeline includes both “Harm-Increasing” (HI) events and “Harm Reducing” (HR) events, and a few “To Be Determined (TBD)” events. The TBD events are events that in our assessment have not yet reached a final equilibrium for increasing versus decreasing harm. The psychedelic revolution of the 1960s included a massive increase in drug use, which included positive experiences for many users, severely negative experiences for some users, and clearly inequitable law enforcement/incarceration for racial/minority groups in the United States. Societal assessment of psychedelic drugs, including marijuana, has continued, however, with increasing valuation of the possible medical uses and nonmedical uses of these drugs. The development of electronic cigarettes not only has the potential for reducing the severe harms associated with conventional cigarette use and of assisting some cigarette users to stop but also has the potential to create nicotine addiction in many youth. The eventual harms/positives balance for these developments many depend upon the societal mechanisms for regulating their use more than the intrinsic properties of the drugs themselves.

Historical timeline of harm reducing and harm-increasing events in the United States

- •

Late 1800s to early 1900s : Gradual transition of opioid use from medical prescription to illicit activities. (HI)

- •

January 23, 1912 : The International Opium Convention is held at the Hague, becoming the first international drug control treaty signed into law. (HI)

- •

Late 1910s to early 1920s : Morphine maintenance clinics in multiple US cities. Shreveport, LA best known of these clinics. (HR)

- •

1914 : Harrison Act outlawing narcotic drugs. (HR)

- •

1914 : Cocaine made illegal. (HI)

- •

1918 : Prohibition begins. Great increase in organized crime. (HI)

- •

1930 : Creation of the federal Bureau of Narcotics, headed by Harry Anslinger. (HI)

- •

1933 : Prohibition ends. Some criminal organizations move into distribution of heroin and cocaine. (HR, but some HI)

- •

1945 : With end of World War II, increased importation of heroin into the United States, through the French Connection. (HI)

- •

1964 : Surgeon General’s report on the health risks of smoking. (HR)

- •

Mid 1960s : Development of methadone maintenance treatment for heroin addiction. (HR)

- •

Late 1960 through 1970s : Psychedelic drug revolution, including increased use of marijuana. (TBS)

- •

1970s and 1980s : Increased use of heroin and cocaine. (HI)

- •

Early 1970s : Original “War on Drugs,” but including large expansion of methadone maintenance treatment programs. (HI, but some HR)

- •

Late 1970s : Rapid transmission of HIV among PWID in the northeast United States. (HI)

- •

1980 : Mothers Against Drunk Driving founded. Currently has chapters in all US states. (HR)

- •

1981 : AIDS outbreak first observed among PWID. (HI)

- •

Mid-1980s : Outreach HIV education programs implemented for PWID. (HR)

- •

Mid-1980 and 1990s : Crack cocaine epidemic, violence associated with distribution of crack, increased “War on Drugs” with severe penalties for possession and sale of crack. Spread of HIV through unsafe sex associated with crack use. (HI)

- •

1988 : First syringe exchange in United States in Tacoma, WA. Founding of North American Syringe Exchange Network. (HR)

- •

Late 1980s to present : Continued expansion of syringe exchange programs in the United States, currently there are approximately 400 syringe exchange programs in the country. (HR)

- •

1988 : Initial ban on use of federal funds for supporting syringe exchange operations. (HI)

- •

1989–93 : US National Commission on AIDS advocates for legal access to sterile injection equipment and increased treatment for substance use disorders. Inclusion of PWUD as a protected class in the Americans with Disabilities Act. (HR)

- •

Early to late 1990s : Accumulation of evidence supporting effectiveness of syringe exchange programs. Increase in numbers of programs in the United States. (HR)

- •

1996 : Development of combined antiretroviral treatments for HIV infection. (HR)

- •

2000 onward : Implementation of public health scale “combined prevention and care” (syringe service programs, leading to “ending HIV epidemics” in many high-income settings). (HR)

- •

2000 onward : Increase bans on smoking in public places. (HR)

- •

2002 : FDA approval of buprenorphine for the treatment of addiction. (HR)

- •

2000 onward : Opioid epidemic in United States, with overprescription of opioid analgesics, with transitions to injecting and to heroin use. Syringe exchange programs and MAT expand but with local resistance in many areas. (HI)

- •

Mid-2000s : Development and commercialization of electronic cigarettes, widespread use by teens in mid-2010s. (TBD)

- •

January 2001 : Distribution of naloxone for reversing opioid overdoses at Chicago Recovery Alliance for all staff, volunteers, and participants, gradually spreading in United States. (HR)

- •

2011 : Discovery of direct acting antiretrovirals (DAAs) for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection.

- •

2012 onward : Medical marijuana and recreational marijuana laws adopted in many states. (HR)

- •

2013–16 : HIV outbreak among PWID in Scott County, IN. (HI)

- •

January 2016 : Lifting of ban on use of federal funds to support syringe exchange programs, though federal funds cannot be used for purchase of syringes. (HR)

- •

2016 onward : Widespread distribution of fentanyl in illicit drug distribution. (HR)

- •

2016 onward : Consideration of and planning for safer injection facilities, but federal opposition has prevented implementation. (HR)

- •

2017 : Declaration of opioid epidemic as a public health emergency. (HR)

- •

2019 : “First Step” Act to reform drug laws—reduce criminal penalties for drug possession. (HR)

This historical timeline clearly demonstrates that the history of drug use and harm reduction in the United States has not been a simple or linear process. Events that have increased drug use harms have alternated with events that have promoted harm reduction. Harm reducing activities have often followed harm-increasing events, though often with considerable time between the harm augmentation event and a harm reduction response. We do believe, however, that the overall trend is toward increased harm reduction as a result of greater scientific understanding of drug use disorders and which interventions actually reduce drug-related harms, as well as the growing acceptance of health as a human right.

Harm reduction and the current opioid epidemic

The conceptual analyses of what harm reduction is not and what harm reduction is can provide an overall framework for applying harm reduction to the current opioid epidemic. The historical timeline lists development of specific harm reduction interventions for which there are strong evidence bases and should be utilized in addressing the current epidemic. We would note the following interventions are likely to have the greatest positive impact within the United States:

- 1.

Outreach to persons who use drugs to provide factual information about hazards of specific forms of drug use, to develop trusting communications between health workers and persons who use drugs, and to provide information on how to obtain services for drug-related problems

- 2.

Syringe service programs, that include syringe exchange and the most other health and social services as feasible

- 3.

MAT for opioid use disorders

- 4.

Distribution of naloxone to reverse opioid overdose

- 5.

Safer injection facilities to prevent fatal drug overdoses and transmission of HIV and HCV, and to provide referrals to substance use treatment when these become practical in the United States [ ]

There is sufficient evidence to recommend against:

- 6.

Incarceration of people for possession of small quantities of currently illicit drugs

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we would recommend:

- 7.

Community education to reduce stigmatization of drug use

The current opioid epidemic in the United States is a severe and multifaceted challenge to public health. Harm reduction provides multiple tools for addressing this epidemic, but the epidemic is likely to change over time, creating a need for vigilance and a likely need for developing new harm reduction interventions.

Tips for clinicians

In this chapter, we have discussed harm reduction as a set of public policies and public health interventions that recognize the innate desires of human beings to use various psychoactive drugs and that medical and social science can be used to minimize the individual and societal harms often associated with psychoactive drug use. Harm reduction can also be a critical component of healthcare provide/patient relationships. We thus would like to conclude this chapter with suggested guidance for infectious disease healthcare providers when working with persons who use drugs:

- 1.

Open, nonstigmatizing conversations about drug use so as to better understand individual health risks and offer appropriate, patient-centered interventions. Understand that not all individuals are ready for abstinence, but that any harm reduction can improve health outcomes.

- 2.

Encourage use of sterile syringes if persons inject drugs. Prescribe syringes, if individuals live in a state where laws require prescriptions and permit prescribing of syringes. Discuss the importance of not sharing cookers, cotton, pipes, and other drug using paraphernalia, in addition to syringes to prevent acquisition of infectious diseases, particularly HCV.

- 3.

Provide buprenorphine treatment so that you can treat both infectious diseases and opioid use disorders in same setting. Refer and link patients to other buprenorphine providers or methadone if not available in your clinical setting.

- 4.

Know local community-based organizations, such as syringe exchange programs, that aid in drug user health and refer and link patients to these groups.

- 5.

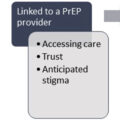

Offer PrEP to PWID, particularly if PWID are concurrently having nonprotected sex.

- 6.

Treat HCV-positive sexual and drug using partners together, to prevent reinfection of the social unit.

- 7.

Prescribe Naloxone to prevent opioid overdose.

- 8.

Believe in the right to life even for people who use drugs.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree