Nonpharmacologic Management of Pain

Gayle L. Byker

Dona Leskuski

Arecent meta-analysis revealed that 64% of patients with cancer experience pain (1). Medications are currently the mainstay of treatment for cancer pain. Despite internationally accepted guidelines for the medical treatment of cancer pain, the fact remains that patients’ symptoms are often inadequately treated (2). In 1986, the World Health Organization developed an analgesic ladder that makes recommendations for the appropriate and effective treatment of cancer pain with the use of nonopioid and opioid analgesic medications in addition to adjuvant medications based on pain intensity and the escalating severity of pain. While this ladder has been the subject of some debate, the concept of a guideline-based approach that emphasizes pharmacologic management of cancer pain has not.

Another approach has been growing in popularity in recent years, namely, nonpharmacologic management of pain as an adjunct or a complement to traditional medication-based treatment. Nonpharmacologic therapies are widely used among cancer patients (3,4,5). In 2001, the American Cancer Society and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network published cancer pain control guidelines for patients and families that recommend nonpharmacologic modalities for cancer pain as an adjunct to medications (6). The American Pain Society has also developed guidelines for cancer pain management that emphasize the combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities (7).

Numerous nonpharmacologic modalities are employed for the treatment of cancer pain, more than could be adequately described in the context of this chapter. Further, many of these modalities lack a rigorous evidence base for their efficacy (8). Most of the studies that have been performed to date are small and biased. Like conventional medications, nonpharmacologic treatments carry with them the risk of side effects and adverse reactions and should be subject to the same standard of clinical scrutiny.

This chapter focuses on the most widely used and accepted nonpharmacologic interventions for cancer pain. Particular attention will be paid to those modalities for which there is an empirical evidence of efficacy in treating cancer-related pain. Broadly, these modalities fall under the categories of psychosocial and physiatric interventions. Psychosocial interventions can be further conceptualized as self-regulatory approaches, psychoeducation, and cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs). More commonly used physiatric approaches fall under the categories of nociceptive modulation and restoration of normal biomechanics. Finally, the chapter highlights promising new directions in the field of nonpharmacologic cancer pain management.

RATIONALE FOR NONPHARMACOLOGIC INTERVENTIONS

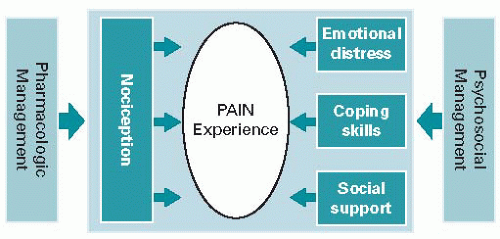

In his Treatise of Man published in 1664, French philosopher René Descartes described the “pain pathway” as a simple matter of a single neural thread relaying information about a stimulus in the body to the brain (9). Cancer pain specialists now believe the experience of pain to be far more complex. Melzack’s neuromatrix theory broadens the concept of a single neural thread to include a neural network that integrates input from somatosensory, limbic, and thalamocortical systems (10,11). The complex experience of pain is therefore understood to reflect the activity of numerous brain inputs. It is thought to be the result of information relayed to the brain not only from peripheral nociception but also from other aspects of sensorimotor, cognitive, and emotional processing (12) (Figure 3.1).

There is a broad and expanding volume of literature on the psychosocial factors that influence the experience of pain. First, psychological distress is known to directly impact the experience of pain (13). Specifically, studies have shown that depression, anxiety, anger, and mood disturbances are correlated with higher levels of perceived cancer-related pain (13,14). Conversely, patients with higher levels of social support report lower levels of cancer pain intensity (15,16).

Additionally, there are numerous coping styles that have been shown to influence the experience of pain. Self-efficacy is the belief that one has the capability to achieve a desired outcome, such as coping with pain. One study revealed that

self-efficacy is a significant predictor of the development of pain during bone marrow transplantation (17). Passive coping is another psychosocial factor that influences the perceptions of pain. This coping mechanism is characterized by helplessness and uses strategies that relinquish control of pain to others or allow other areas of life to be adversely affected by pain (18). The use of this maladaptive method of coping has been shown to increase the experience of cancer-related pain (19).

self-efficacy is a significant predictor of the development of pain during bone marrow transplantation (17). Passive coping is another psychosocial factor that influences the perceptions of pain. This coping mechanism is characterized by helplessness and uses strategies that relinquish control of pain to others or allow other areas of life to be adversely affected by pain (18). The use of this maladaptive method of coping has been shown to increase the experience of cancer-related pain (19).

Figure 3.1. The complex experience of pain. (Adapted from Breitbart W, Gibson C. Psychiatric aspects of cancer pain management. Primary Psychiatry 2007;14:81-91.) |

Of the various forms of coping that have been studied, pain catastrophizing has proven to be one of the most consistent predictors of pain and disability (20). This method of coping refers to a negative response style characterized by a tendency to ruminate on aspects of the pain experience, to exaggerate the threat value of pain, and to adopt a helpless orientation toward pain (21). A study of 70 patients with gastrointestinal cancer showed that caregivers of patients who catastrophized rated the patient as having significantly more pain and engaging in more pain behaviors than patients who did not engage in catastrophizing (22).

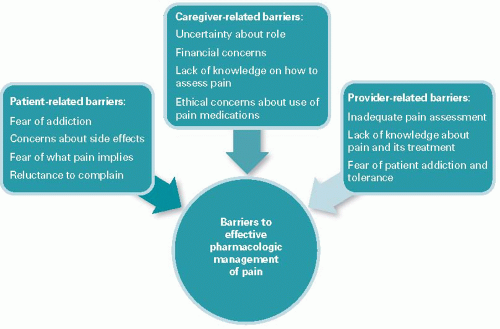

Other important psychosocial factors contributing to the pain experience are the beliefs and attitudes of patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers that function as barriers to effective pharmacologic pain management. Patient-related barriers include fear of addiction, concern about side effects, fear of what pain implies, and reluctance to complain or distract their physicians (23,24). Barriers experienced by caregivers include uncertainty about their role in pain management, financial concerns, lack of knowledge of how to assess pain, and ethical concerns about the use of pain medications (25,26). Healthcare provider-related barriers include inadequate pain assessment, inadequate knowledge about pain and its treatment, and fear of patient addiction and tolerance (27) (Figure 3.2).

Clearly, the experience of pain is affected not only by direct injury to tissue but also by cognitive, emotional, and psychosocial contributions. It stands to reason, therefore, that a pain management approach that includes therapies to address these various dimensions of suffering will more effectively treat the whole patient with cancer who is experiencing pain.

PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTIONS FOR CANCER PAIN

Psychosocial interventions have been shown to lead to improved pain control in patients with cancer-related pain (28). There are several psychosocial approaches that have strong or promising empirical evidence to support their efficacy in treating such patients. These approaches can be grouped into three broad categories: self-regulatory approaches, psychoeducation, and CBTs. All of these modalities can be used safely and effectively in combination with pharmacologic approaches to cancer-related pain treatment.

Self-regulatory Approaches

Relaxation

Relaxation is the central theme running through many self-regulatory techniques employed for pain management in patients with cancer. Relaxation therapies, techniques, and training will be referenced frequently in subsequent sections of this chapter as important components of most

self-regulatory approaches, including biofeedback, hypnosis, and CBT. Relaxation focuses on the identification of sources of tension within the mind and body, followed by the practice of systematic methods such as deep or diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and visualization or imagery to reduce tension and alter the perception of physical pain (29). It may improve pain symptoms by reducing the physical tension and emotional stressors and by facilitating the ability to become comfortable, rest, and fall asleep (30). Relaxation has been shown to be effective for chronic pain management of a variety of noncancer illnesses, including migraine (31), musculoskeletal pain (32), and low back pain (33).

self-regulatory approaches, including biofeedback, hypnosis, and CBT. Relaxation focuses on the identification of sources of tension within the mind and body, followed by the practice of systematic methods such as deep or diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and visualization or imagery to reduce tension and alter the perception of physical pain (29). It may improve pain symptoms by reducing the physical tension and emotional stressors and by facilitating the ability to become comfortable, rest, and fall asleep (30). Relaxation has been shown to be effective for chronic pain management of a variety of noncancer illnesses, including migraine (31), musculoskeletal pain (32), and low back pain (33).

Studies have repeatedly found relaxation to be one of the most frequently used complementary therapies by cancer survivors (34). A controlled study in hospitalized oncology patients performed in the 1990s examined the efficacy of relaxation techniques involving deep breathing, muscle relaxation, and imagery compared with no relaxation (35). Results showed a significant reduction in subjective pain ratings and in nonopiate, as-needed analgesic intake. Previous studies also support the use of relaxation in the context of hypnosis and imagery as effective adjunctive pain interventions in terminally ill cancer patients (36).

Although the implications for relaxation in treating cancer-related pain are promising, the data remain inconsistent. A recent review found that pain was the primary focus of four efficacy trials of relaxation in cancer patients, with beneficial effects demonstrated in three (30). Samples included inpatients and outpatients with cancer-related pain as well as women with early-stage breast cancer. One study randomized 58 women with breast cancer to practice progressive muscle relaxation or receive massage therapy for 30-minute sessions 3 times a week for 5 weeks (37). The control group received standard treatment. Pain assessments were completed after the first and last sessions. Both the progressive muscle relaxation group and the massage group had significantly lower pain scores after the first and last sessions compared with the standard treatment group.

A second study randomized 57 patients taking opiates for chronic cancer-related pain to relaxation, distraction, positive mood interventions, or wait-list control (38). Patients in the three intervention groups were given audiotapes describing the cognitive-behavioral techniques and written instructions on practicing regularly at home. Patients who practiced relaxation and distraction reported significantly lower pain intensity immediately after listening to the cognitive-behavioral tapes as compared with the control group. The pain reduction was not long-lasting, however, with no significant difference in pain intensity or pain interference found between groups 2 weeks after the intervention.

A third smaller study examined pain in patients with advanced cancer (39). Twenty-four patients were randomized to receive either six electromyography biofeedback-assisted relaxation sessions over a 4-week period or conventional care. They found that relaxation training supplemented with electromyography biofeedback was effective in reducing cancer-related pain in patients with advanced cancer. They postulated that this pain reduction is achieved through attenuation of physiologic arousal.

The earliest of the four studies, however, found no significant differences in pain between daily relaxation and distraction alone in patients undergoing surgical skin cancer resection (40). Forty-nine patients with skin cancer were randomly assigned to practice relaxation techniques 20 minutes per day prior to surgical excision versus reading a book for 20 minutes a day. There was no significant difference in pain scores between the two groups either before or after skin cancer removal surgery.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is a process for monitoring physiologic functions such as breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure and then altering that function, most commonly through relaxation therapy. Instrumentation is used to measure and relay information to the patient regarding their vital signs, electroencephalography or brain waves, electromyography or muscle tension, and peripheral skin temperature. Over time and with the guidance of a trained practitioner, the patient learns to control these physiologic functions without the need for instrumentation in order to improve symptoms including pain (41).

A National Institutes of Health Technology Assessment Panel recognized the benefits of biofeedback for the treatment of chronic pain in 1996 (42). Since then a number of studies have shown biofeedback to be effective in the treatment of specific pain syndromes. Biofeedback has been shown to help reduce chronic low back pain, joint pain, headache, and procedural pain (43). A recent large meta-analysis of 94 trials studying biofeedback for migraine and tension headaches found medium to large effect size for all types of biofeedback that remained stable for an average of 15 months (44,45).

A review of the use of mind-body interventions for chronic pain in older adults found that these modalities are feasible and likely safe in older patients (46). Another examination of the use of biofeedback for chronic pain in older adults found ample evidence that older adults respond well to behavioral interventions such as biofeedback (47). Comparisons of older versus younger patients reveal that older patients are as capable as younger patients of readily acquiring the physiologic self-regulation skills taught in biofeedback-assisted relaxation training. In fact, one study comparing 58 older and 59 younger patients found that older participants achieved increases in skin temperature and decreases in respiration rate that were similar to those of younger participants, using the same training protocol and an equal number of training sessions (47). Older patients also reported a significantly greater decrease in current and maximum pain scores compared with their younger counterparts.

The body of evidence supporting biofeedback specifically for the treatment of cancer-related pain is still small. A randomized controlled trial referenced earlier in this chapter studied the effect of electromyography biofeedback-assisted

relaxation in cancer-related pain in patients with advanced cancer (39). Results showed that patients in the treatment arm had significantly lower pain intensity scores than those receiving conventional care. Patients receiving biofeedback had a pain score reduction of 2.29 points from baseline on the 0 to 10 Brief Pain Inventory scale, which was statistically significant when compared with the control group. Sixty-seven percent of patients in the study groups reported a reduction of at least 30% in pain intensity from baseline and 50% obtained a reduction of at least 50% in pain intensity from baseline. In contrast, patients in the control arm reported an average increase of 14% in pain intensity from baseline.

relaxation in cancer-related pain in patients with advanced cancer (39). Results showed that patients in the treatment arm had significantly lower pain intensity scores than those receiving conventional care. Patients receiving biofeedback had a pain score reduction of 2.29 points from baseline on the 0 to 10 Brief Pain Inventory scale, which was statistically significant when compared with the control group. Sixty-seven percent of patients in the study groups reported a reduction of at least 30% in pain intensity from baseline and 50% obtained a reduction of at least 50% in pain intensity from baseline. In contrast, patients in the control arm reported an average increase of 14% in pain intensity from baseline.

An earlier analysis of the biofeedback literature suggested that the improvement in pain with biofeedback is confounded by the use of relation techniques in order to achieve the desired alterations of physiologic functions (48). In fact, relaxation techniques are usually an integral component of biofeedback training, and whether biofeedback can independently improve pain without relaxation may be difficult to examine.

Hypnosis and Imagery

Hypnosis is the induction of a deeply relaxed state, with increased suggestibility and suspension of critical faculties (49). Once in this state of heightened and focused concentration, known as a hypnotic trance, patients can be given therapeutic suggestions to change their perception of pain (14). One study demonstrated that the hypnotic effects on postsurgical pain are mediated in part by response expectancies and emotional distress (50). The efficacy of hypnosis has been well established for procedural pain (51,52), anticipatory nausea and vomiting (53), and various types of chronic pain (54,55,56).

Hypnosis for cancer-related pain has also become the subject of considerable research. A study published in 1983 by Spiegel and Bloom randomized 58 patients with metastatic breast cancer to group therapy with or without imagery-guided hypnosis and found that women receiving hypnosis experienced significantly less pain sensation and suffering than the control group (57). There was no difference in pain frequency or duration. In two studies in the early 1990s, Syrjala et al. found that hypnosis with guided imagery improved mucositis pain associated with bone marrow transplantation (36,58). Additionally, the National Institutes of Health Technology Assessment Panel found a strong evidence for hypnosis in alleviating cancer-related pain (42).

Hypnosis and imagery have an established role in the management of acute procedural pain in patients with cancer, particularly in pediatric patients. Liossi et al. examined venipuncture-induced pain in children with cancer in the age group of 6 to 16 (59). Forty-five pediatric patients were randomized to receive local anesthetic, local anesthetic plus hypnosis, or local anesthetic plus attention. Patients receiving local anesthetic plus hypnosis reported significantly less procedure-related pain and demonstrated less behavioral distress during the procedure than patients in the other two groups. The same group of researchers performed two trials examining hypnosis in pediatric cancer patients undergoing lumbar puncture for hematologic malignancies and obtained similar results (60,61).

In a study of adult patients with cancer, Montgomery et al. randomized 200 women undergoing excisional breast biopsy or lumpectomy to a 15-minute presurgical hypnosis session with a psychologist versus nondirective empathic listening prior to surgery (62). On a scale of 0 to 100, women in the hypnosis group reported significantly less pain intensity (mean of 22.43 versus 47.83), less pain unpleasantness (mean of 21.19 versus 39.05), and less discomfort (mean of 23.01 versus 43.20) compared with control. Hypnosis patients also required significantly less propofol and lidocaine than patients who did not receive hypnosis.

Elkins et al. conducted a prospective randomized study of 39 patients with advanced stage cancer and malignant bone disease (63). Patients were randomized to receive either supportive attention or weekly hypnosis sessions followed by instructions and audiotapes for self-hypnosis. All participants received four individual sessions and rated their pain pre- and post-session. Patients who received the hypnosis intervention demonstrated a significant decrease in pain compared with those receiving supportive attention. There was a significant reduction in post-session pain by the second session which remained significant across all remaining sessions.

Overall, hypnosis is effective in alleviating pain in patients with cancer, particularly those undergoing brief procedures and bone marrow transplantation. When practiced by experienced hypnotherapists, hypnosis can serve an important role in the nonpharmacologic management of cancer pain.

Psychoeducation

Education programs are among the most common methods of addressing barriers to cancer pain management (64). This intervention, which is intended to improve knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain and analgesia, has been extensively researched (65). Pain education is provided to patients, their caregivers, or both and consists of a variety of methods, including didactic or coaching sessions, role modeling, and audio, video, and written material. In a series of papers, de Wit et al. reported on the effectiveness of a tailored pain education program, which included education about basic principles of pain and pain treatment, instruction in the use of a pain diary, instruction in simple nonpharmacologic pain management techniques, as well as encouragement to contact healthcare providers to talk about the pain experience (66,67,68,69).

Patient Education

There is a substantial body of literature in the area of patient education for cancer-related pain. A recent meta-analysis quantified the benefit of patient-based educational interventions in the management of cancer pain (70). Twenty-one controlled trials (19 randomized) totaling 3,501 patients were examined, with 15 included in the meta-analysis. Compared with usual care or control, educational interventions reduced average pain intensity by more than 1 point on a 0 to 10 scale

and reduced worst pain intensity by just under 1 point. There was no significant benefit of education on reducing interference with daily activities.

and reduced worst pain intensity by just under 1 point. There was no significant benefit of education on reducing interference with daily activities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree