Nonpharmacologic Management of Pain

Francis J. Keefe

Amy P. Abernethy

Laura S. Porter

Lisa C. Campbell

Pain is a prevalent and significant problem for persons with cancer. At present, medications are the mainstay of cancer pain management. Despite the fact that medications help many patients with cancer manage pain, there continue to be many patients in whom cancer pain is not effectively managed. Population-based studies demonstrated that in 1969, 66% of patients with cancer complained of pain; in 1987, 72% reported the symptom; and in 1995, 88% reported pain and 66% reported “very distressing” pain (1, 2). In response, cancer pain management guidelines have been developed, recommending varying therapeutic building blocks. In 1986, the World Health Organization developed an analgesic ladder to guide the use of pharmacotherapy on the basis of the severity of cancer pain that involved the use of nonopioid and opioid medications with or without adjuvants for escalating severity of pain. Although the validity of the analgesic ladder has been questioned, the basic notion of a guideline-based approach emphasizing medication management has not. More recently, the American Pain Society (APS) developed a cancer pain management guideline that emphasizes pharmacologic strategies and recommends combining these with nonpharmacologic strategies (3).

A wide array of nonpharmacologic interventions is currently being used in the management of cancer pain. A comprehensive review of all of these interventions is not possible in the context of the current chapter. Furthermore, many of these interventions have not been tested in rigorous clinical trials, making a critical analysis of their efficacy difficult, if not impossible.

To illustrate the potential utility of nonpharmacologic interventions for cancer pain, this chapter focuses on a subset of these interventions that are becoming widely used and for which there exists an empirical basis: psychosocial interventions. This chapter is divided into three sections. In the first section, we review the rationale for psychosocial interventions. In the second section, we briefly describe several widely used interventions [psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), hypnosis and imagery, and caregiver-assisted approaches] and critically evaluate their efficacy on the basis of randomized clinical trials. In the final section, we highlight important issues related to the use of psychosocial interventions in cancer pain management.

Rationale for Psychosocial Interventions

Traditionally, cancer pain management has been based on a biomedical model of pain. The chief tenet of this model is that pain is a sensation or symptom due to underlying tissue damage or injury. In cancer, pain can be caused by the tumor itself; tissue damage related to treatments such as surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy; cancer-related infections; immobility; or diagnostic procedures. The biomedical model maintains that pain is most effectively treated by identifying the underlying tissue damage and correcting it.

Clinical observations and research, however, indicate that the traditional biomedical model has limitations. First, the amount of pain that a patient with cancer reports does not correlate well with underlying tissue damage. Some patients with minimal evidence of tissue damage report having excruciating pain, whereas others with considerable tissue damage report little or no pain. Second, even in patients who report the same level of pain, the level of pain-related disability can vary enormously, with some patients becoming much more disabled by their pain than others. Finally, treatments designed to eliminate the underlying cause of cancer pain (e.g., removal of a tumor) often fail to abolish or significantly reduce pain.

Because of these limitations, cancer pain specialists have looked at newer and more complex theories of pain to direct their pain management efforts. Typical of these newer theories is Melzack’s neuromatrix theory (4). This theory maintains that pain is a complex and dynamic experience that has sensory, affective, and cognitive dimensions, which are served by underlying somatosensory, limbic, and thalamocortical systems. A key tenet of this theory is that there is a neural network in the brain that integrates multiple inputs to produce pain. The complexity of pain, therefore, reflects the activity of multiple brain inputs (i.e., sensory, cognitive and emotional inputs, and inputs from intrinsic neural inhibitory and stress regulation systems).

The neuromatrix theory has important implications for cancer pain management. First, this theory and the theory it evolved from, Melzack and Wall’s gate control theory (5), provide a conceptual rationale for broadening the focus

of assessment efforts to include consideration of cognitive, emotional, social, and cultural factors that can influence cancer pain and disability. Second, by emphasizing the effects of cognition and emotion on pain, this theory has stimulated more widespread use of psychotropic medications (e.g., antidepressants) in cancer pain management. Finally, this theory has highlighted the potential utility of psychosocial interventions in enhancing pain control.

of assessment efforts to include consideration of cognitive, emotional, social, and cultural factors that can influence cancer pain and disability. Second, by emphasizing the effects of cognition and emotion on pain, this theory has stimulated more widespread use of psychotropic medications (e.g., antidepressants) in cancer pain management. Finally, this theory has highlighted the potential utility of psychosocial interventions in enhancing pain control.

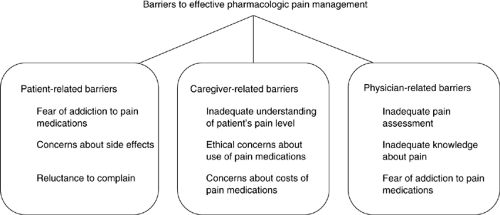

Over the last 20 years, converging lines of evidence have identified important domains of psychosocial factors that can influence the cancer pain experience (6, 7). One important domain is made up of the beliefs and attitudes of the patient, caregiver, and physician that function as barriers to effective pharmacologic pain management. Patient-related barriers include concerns about analgesics, fear of addiction, concerns about side effects, fear of the implication of pain, and reluctance to complain (8). Caregiver-related barriers include an unclear role, cost concerns, inadequate understanding of the patient’s pain level, and personal ethical concerns about the use of pain medications (9, 10). Doctor-related barriers include inadequate pain assessment, inadequate knowledge about pain, fear of tolerance, and fear of addiction (11, 12, 13). (Fig. 5.1)).

Psychological distress is a second important domain. There is evidence that patients who have high levels of psychological distress experience significantly higher levels of cancer pain than those who report low levels of psychological distress (6). In particular, studies have shown that depression, anxiety, anger, and overall high levels of mood disturbance are linked to the experience of more severe cancer pain (6).

Self-efficacy or the belief that one has a capability to achieve a desired outcome, for example, pain control, is a third important domain. Syrjala and Chapko (14) reported that pretreatment self-efficacy was a significant predictor of the development of pain during bone marrow transplantation therapy. Keefe et al. (15) found that caregivers of patients with cancer who reported high personal self-efficacy with regard to their ability to help their patient partner manage cancer pain at the end of life had much lower levels of caregiver strain and negative mood and increased positive mood, and their patient-partners reported that they were more energetic, spent less time in bed, and had overall higher levels of physical well-being.

Pain catastrophizing, the fourth domain, has been defined as “an individual’s tendency to focus on and exaggerate the threat value of painful stimuli and negatively evaluate one’s own ability to deal with pain” (16). Of the various forms of pain coping that have been studied, pain catastrophizing has proven to be one of the most consistent predictors of pain and disability (17). In a study of patients with gastrointestinal cancer, we found that patients who engaged in pain catastrophizing reported much higher levels of pain and pain behavior (18).

Social support is a fifth important domain that can influence the pain experience. A review of the literature on social support and cancer pain found that patients who reported high levels of social support experienced much lower levels of pain (6). Indices of social support such as resilience of the social network, level of social activities, and social functioning were all found to be related to decreased pain.

A final important domain that can influence cancer pain is the existential domain. Pain can be a constant reminder of the cancer; persistent or progressive pain a harbinger of advancing disease (19). Hence, progressive pain may imply worsening disease and incite a whirlwind of existential concerns such as “why me?” Conversely, finding meaning in the cancer experience may include reevaluation of the disease and its pain as positive, answering “why me?” by making sense of the disease on a more spiritual or existential level (20). Reappraisal and finding meaning is critical in the coping process. Psychological approaches to pain control can also support the process of finding meaning in and relief from existential suffering.

Psychosocial Interventions for Cancer Pain

Evidence that psychological factors can exacerbate pain associated with cancer has heightened interest in the role of psychosocial interventions in cancer pain management. We recently conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral therapies for cancer pain management and found that these interventions generally led to improved pain control, with an overall effect size of 0.232 [confidence interval (CI) = 0.072–0.392] suggesting that these interventions, as a group, are beneficial as adjuvants in the cancer pain treatment plan (21).

Psychosocial interventions that have been empirically tested can be grouped into four broad categories: cancer pain psychoeducation, CBT, hypnosis and imagery, and caregiver-assisted approaches. An advantage of all of these approaches

is that they can be combined with other cancer pain therapies, taking an “adjuvant” role.

is that they can be combined with other cancer pain therapies, taking an “adjuvant” role.

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducational interventions in pain management were developed in response to the recognition that many patients lack basic knowledge about pain and its management and have misconceptions, particularly about pain medication, that constitute barriers to adequate pain relief. Psychoeducation is probably the most widely used psychosocial intervention in pain management and serves as a natural complement to medical interventions. Several components are commonly included in psychoeducational interventions, such as education about basic principles of pain, instructions for monitoring pain (e.g., keeping a pain diary), guidelines for when to contact health care providers, and recommendations for how to communicate with health care providers about pain. The interventions are typically delivered by nurses who are specially trained for this purpose and are supplemented with videotapes and/or written materials. Interventions can also be tailored to individual patients by including an assessment phase in which the individual learning needs of patients are identified through interviews or questionnaires (22, 23).

The effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions has been demonstrated in a number of recent randomized clinical trials. In a series of papers, De Wit et al. (22, 24, 25, 26). reported on the effectiveness of a tailored Pain Education Program (PEP), which included education about basic principles of pain and pain treatment (given in an oral format supplemented with an audiotape and brochure), instruction in how to report pain in a pain diary, and instruction in simple nonpharmacologic pain management techniques (i.e., cold, heat, relaxation, and massage), as well as encouragement to contact health care providers to talk about the pain experience. The intervention was delivered by a nurse in one 30–60-minute face-to-face session along with two brief (5–15 minute) phone calls during the week after discharge. Results showed that patients who received the PEP intervention had significant increases in pain knowledge and decreases in pain intensity compared to patients who were randomized to standard care. However, pain relief was primarily restricted to the group of patients with better functioning at baseline, indicating that this brief intervention may not be adequate for patients with more complex pain problems.

A randomized controlled trial conducted by Oliver et al. (27) tested the effects of a single-session education and coaching intervention in patients with cancer experiencing at least moderate levels of pain. The intervention was individualized and primarily addressed misconceptions about pain treatment and encouraged communication with health care providers about pain control. Patients receiving this intervention reported significant improvements in average pain severity as compared to controls who received standardized education on controlling cancer pain.

Two studies have tested psychoeducational interventions among hospitalized patients with cancer in Taiwan. The first study (28) randomly assigned patients to receive either a pain education intervention or standard care. Patients in the pain education intervention received a booklet addressing beliefs and concerns about reporting pain and using analgesics that are common among Taiwanese patients with cancer, including fatalism, fear of addiction, the desire to be a “good patient” by not complaining about pain, fear of distracting one’s physician from treating the disease, concern that increasing pain signifies disease progression, and concerns about side effects of analgesics. A research assistant spent 30–40 minutes reviewing the content of the booklet with the patient and answering questions. Compared to patients in the control group, patients receiving the pain education intervention demonstrated significant improvements in self-reported barriers to pain management and medication adherence. However, group differences in pain intensity and pain interference were not significant.

The pain education intervention tested in the second study (29) consisted of a booklet that included information on how to prevent or manage side effects of pain medication, an introduction to psychosocial pain interventions, ways to assess and monitor pain intensity, ways to communicate pain problems to health care professionals, and information on common misconceptions about using analgesics. Results indicated that the pain education intervention was effective in reducing pain intensity, negative beliefs about opioids, pain endurance beliefs, and pain catastrophizing, and in increasing a sense of control over pain.

Miaskowski et al. (23) conducted a randomized clinical trial of a self-care intervention in patients with oncologic disorders who had pain from bone metastases. The intervention, PRO-SELF, involved three home visits and three telephone contacts by a nurse and included tailored educational content on pain management and nurse counseling on pain and side effect management, use of a weekly pillbox, and communication with health care providers about unrelieved pain and the need for a change in analgesic prescriptions. Results indicated that patients receiving the intervention had significant reductions in pain intensity and were more likely to have the most appropriate type of analgesic prescription as compared to controls.

A patient- and caregiver-focused cancer pain education strategy was studied in a large randomized controlled trial involving palliative care patients with advanced illness in Australia; >90% of patients had cancer. In this study, the intervention focused on overcoming patient and caregiver barriers to better pain management (e.g., concerns about addiction and side effects, fears that pain implies progressive cancer) in an effort to improve receptiveness to critical information about pain control in the palliative care setting (e.g., round-the-clock dosing, early treatment of constipation, and use of nonpharmacologic interventions). An educational outreach visiting format was used. Patients requiring a caregiver at baseline and randomized to the patient- and caregiver-focused intervention had significantly better performance status than those who did not receive the intervention. This improvement was across their entire time in the palliative care phase of their illness (mean 5 months), a very difficult time in the illness trajectory to modify function. Reports of pain were not significantly improved, and this is still being explored.

Table 5.1 Cognitive-Behavioral Pain Management Protocol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A recent study targeting underserved African American and Hispanic patients with cancer found less promising results (30). The intervention used in this study consisted of a culturally specific video and a booklet on pain management. Patients and their family members watched the video, which addressed misconceptions about pain treatment and the importance of reporting pain and insisting on pain relief, and then met with a research nurse who answered questions and emphasized the importance of reporting pain to the health care team. Contrary to expectations, the intervention did not affect pain intensity, pain interference, quality of life, or functional status. The authors speculate that a more intensive education program involving both physicians and patients may be needed for underserved minority patients.

Despite some negative results, the overall pattern of findings suggests that psychoeducational interventions are efficacious in helping patients with cancer manage pain. The interventions that have been tested tend to be brief; although this may be adequate for some patients, others—including medically underserved patients and those with low education and/or complex pain problems—may require more intensive and

multifaceted approaches. Specific features of the interventions, including at what point in the illness trajectory they are delivered, where (inpatient vs. outpatient, home vs. clinic), and by whom, have yet to be evaluated.

multifaceted approaches. Specific features of the interventions, including at what point in the illness trajectory they are delivered, where (inpatient vs. outpatient, home vs. clinic), and by whom, have yet to be evaluated.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree