Neoadjuvant chemoradiation (CRT) is considered one of the preferred treatment strategies for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. This strategy may lead to significant tumor regression, ultimately leading to a complete pathologic response in up to 42% of patients. Assessment of tumor response following CRT and before radical surgery may identify patients with a complete clinical response who could possibly be managed nonoperatively with strict follow-up (watch-and-wait strategy). The present article deals with critical issues regarding appropriate selection of patients for this approach.

Key points

- •

If you are considering a watch-and-wait policy for patients with a complete clinical response (cCR), you should consider treating cT2N0 low rectal tumors with neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

- •

The best tool to assess cCR is digital rectal examination and endoscopy. Endoscopic biopsy results may be misleading.

- •

Radiological imaging does not diagnose cCR; it just confirms it. In the absence of cCR, do not look for radiological evidence to support nonoperative management.

- •

Local excision (full excisional biopsy) is a good tool to assess primary tumor response in patients with near cCR and radiological imaging showing ycT0-2N0.

Introduction

Rectal cancer management has become increasingly complex over the last few decades. The widespread use of neoadjuvant therapies has introduced a new variable, tumor response, which may dramatically change the ultimate surgical decision from radical surgery to local excision, transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), or even no surgery at all. In this setting, surgeons have to consider many aspects of the disease before deciding on a definitive treatment approach.

Introduction

Rectal cancer management has become increasingly complex over the last few decades. The widespread use of neoadjuvant therapies has introduced a new variable, tumor response, which may dramatically change the ultimate surgical decision from radical surgery to local excision, transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), or even no surgery at all. In this setting, surgeons have to consider many aspects of the disease before deciding on a definitive treatment approach.

Indications for neoadjuvant therapy

Classic indications for neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer are mostly derived from randomized controlled studies that showed a local control benefit among patients with cT3-4 or cN+ tumors treated with radiation or chemoradiation (CRT), followed by radical surgery. However, recent updates with a longer follow-up of these same cohorts suggest that the benefits in local disease control following neoadjuvant CRT and radical surgery are marginal or even outweighed by treatment-related toxicities. Therefore, except for circumferential margin positivity, local control is not expected to be significantly increased with the use of neoadjuvant CRT provided appropriate total mesorectal excision is performed, even for cT3 or cN+ disease ( Box 1 ).

- •

Increased rates of second primary cancers

- •

Small-bowel obstruction

- •

Chronic abdominal pain

On the other hand, neoadjuvant radiation alone, CRT, or even chemotherapy alone may lead to significant tumor regression resulting in

- •

Downsizing (significant changes in tumor size)

- •

Downstaging (depth of penetration)

- •

Nodal sterilization

- •

Pathologic complete response (pCR)

Not only does this latter group of patients with pCR have improved oncological outcomes but also the opportunity of being spared from radical surgery and its associated immediate morbidity, mortality, functional disorders, and need for stomas.

The problem is that if you give neoadjuvant therapy only for advanced stage disease, very few patients will develop a complete tumor response (up to 24%). However, neoadjuvant therapy may be extremely useful for the selection of those patients who may avoid a radical operation and, thus, may be used more effectively if more widely adopted to include patients with earlier disease stages. If earlier disease stages are offered this treatment strategy (including cT2N0), complete response may develop more frequently, reaching up to 44% of patients, and would allow more patients to benefit from avoiding radical surgery and associated morbidities.

In a recent study of patients with cT2N0 rectal cancer undergoing CRT followed by full-thickness local excision (FTLE), pCR in the primary tumor (ypT0) was observed in 44% of patients, suggesting that a significant proportion of these patients with an earlier disease stage may benefit the most from neoadjuvant CRT.

Types of neoadjuvant therapy

Considering neoadjuvant therapy will be used for the purpose of tailoring surgical therapy for patients based on the tumor response, strategies associated with significant tumor regression are preferred. Therefore, combined association of chemotherapy and radiation (ie, long-course with hyperfractionated radiation therapy (RT) doses) has been shown to result in greater tumor regression rates and an increased chance of a complete response. In contrast, short-course RT alone may only lead to significant tumor regression if longer intervals between RT completion and assessment of the response are allowed. The standard days to 1-week interval will lead to virtually no chance of developing a pCR.

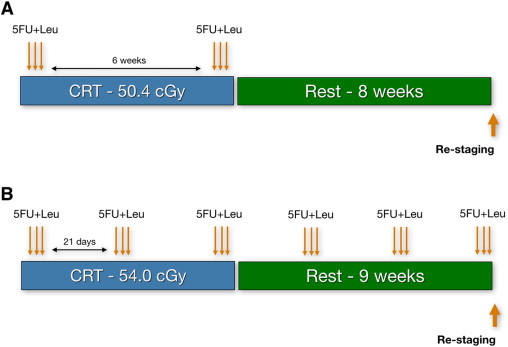

Finally, even though most studies have dealt with radiation or CRT therapies in the neoadjuvant setting, there is a suggestion that chemotherapy alone could provide similar outcomes in terms of rates of pathologic response and, therefore, sparing patients from potentially unnecessary radiation-related toxicities. In fact, a regimen with radiation and an increased number of cycles of chemotherapy has resulted in surprisingly high rates of complete tumor regression (51% complete clinical response [cCR]). It has been the authors’ practice to offer patients this extended CRT regimen, especially considering that the chances of having a complete response are higher ( Fig. 1 ).

Assessing tumor response

Why?

The rationale for assessing the tumor response after neoadjuvant therapy is to define the final treatment strategy based on the current status of the tumor, that is, after therapy.

In a significant proportion of patients undergoing neoadjuvant CRT, complete tumor regression may develop. The problem is that most of the time radical surgery is required to appropriately confirm the presence of a pCR. In an effort to spare patients from potentially unnecessary surgery, colorectal surgeons have attempted to assess the tumor response in order to estimate the pathologic response by clinical, endoscopic, and radiological means.

In this setting, the term cCR has been used for patients with no clinical evidence of residual cancer after neoadjuvant therapy.

It has been suggested that patients with cCR ( using very stringent criteria ) might be offered no immediate radical surgery. Instead, a strict surveillance program, also know as the watch-and-wait strategy , with frequent visits to the colorectal surgeon and the use of multiple staging modalities could possibly provide a safe follow-up. Initial studies trying to estimate the accuracy of clinical assessment in predicting pCR were disappointing. However, more recent studies have shown that clinical assessment can accurately detect pCR when stringent criteria are used.

When?

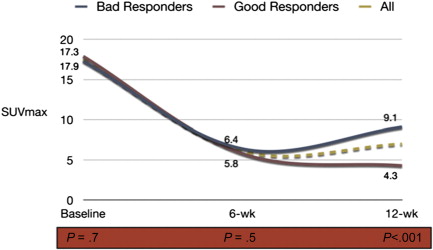

Intervals between CRT completion and the assessment of response may also be relevant. Studies suggest that longer intervals are associated with higher pCR rates. Initially 2 weeks was used, then 6 weeks, and now intervals as long as 12 weeks are considered. There are ongoing randomized studies to address these issues that will provide us further information on the ideal interval between CRT and the assessment of response. There is a chance, however, that intervals will need to be tailored or individualized for each patient, as tumors may respond differently as a function of time to treatment. In a recent study using sequential PET/computed tomography (CT) imaging, patients showed a significant decrease in tumor metabolism between baseline and 6 weeks from standard CRT, estimated by maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax) values. However, between 6 and 12 weeks there were 2 subgroups of tumor metabolism profiles. Although half of the patients developed a further decrease in standard uptake value (SUV) between 6 and 12 weeks, the remaining half developed an increase in SUV, suggesting tumor repopulation ( Fig. 2 ). It will be interesting to see these metabolism profiles after newer and more intensive CRT regimens.

It has been the authors’ practice since 1991, from the beginning of their experience with CRT for distal rectal cancer, to assess the tumor response at least 8 weeks from CRT completion. More recently, however, longer intervals (up to 12 weeks) have been used for most patients.

How?

Response assessment always begins with the characterization of symptoms. Symptomatic patients rarely have complete tumor regression, even though this feature has very low specificity. Digital rectal examination (DRE) is perhaps one of the most relevant tools in tumor response assessment. There is currently no single diagnostic tool that can replace the information given by DRE. Frequently, irregularities of the rectal wall are better felt than seen and should be considered as highly suspicious for residual cancer. No patient is considered for a nonoperative approach in the presence of rectal wall irregularities, mass, ulceration, or stenosis. A cCR is defined as the absence of any irregularity of the rectal wall. The area can be thickened and firm; but to be considered a cCR, the surface has to be regular and smooth.

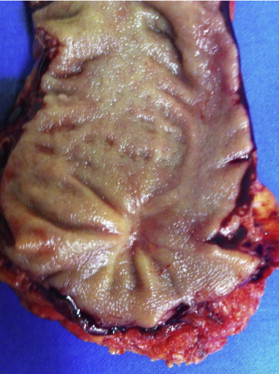

Endoscopic assessment is also very important ( Box 2 ). The presence of any ulceration or mucosal irregularity missed on DRE should prompt additional investigations and usually rules out a cCR ( Fig. 3 ). During flexible or rigid proctoscopy, biopsies are frequently considered for the assessment of response. However, the results of endoscopic biopsies should be interpreted with caution ( Box 3 ).

- •

No residual mass, ulceration or stenosis

- •

Whitening of the mucosa

- •

Telangiectasias

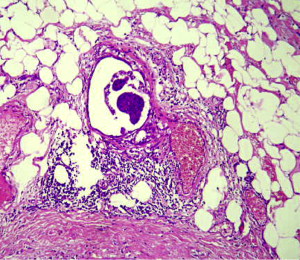

A recent study analyzed the presence of residual cancer among different layers of the rectal wall. Curiously, the presence of cancer cells within deeper layers of the rectum was frequently observed among tumors without cancer at the mucosal level. Therefore, endoscopic mucosal biopsies would lead to false-negative results in a significant amount of these patients. In a review of patients with significant tumor regression after neoadjuvant CRT managed by surgical resection, preoperative biopsies showed a negative predictive value of endoscopic biopsies was as low as 21%. If there is clinical evidence (DRE and endoscopic) of a cCR, forceps biopsies should be interpreted with caution because a negative biopsy cannot rule out microscopic residual cancer.

Local excision of the tumor site

For patients with small residual lesions, the authors usually offer a FTLE, preferably with the use of TEM as a diagnostic procedure ( [CR] )

- •

Small lesions (≤3 cm)

- •

Low lesions, otherwise candidate for abdominal-perineal excision (APE) or a coloanal intersphincteric resection

- •

No evidence of mesorectal dissemination by imaging studies

It has been the authors’ policy to offer strict follow-up to patients with a final pathologic specimen showing ypT0 after this diagnostic FTLE because the risk of lymph node metastases among these patients has been shown to be very low in the setting of neoadjuvant CRT and long intervals (≥8 weeks). This finding is already true for unselected patients with ypT0, whereby the risk of nodal metastases is well less than 10% and in most cases less than 5%. However, with the significant improvements in radiological imaging, particularly with high-resolution magnetic resonance (MR) with the use of diffusion-weighted series and lymphotropic agents, the selection of patients with ycT0N0 is expected to further improve ( Box 4 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree