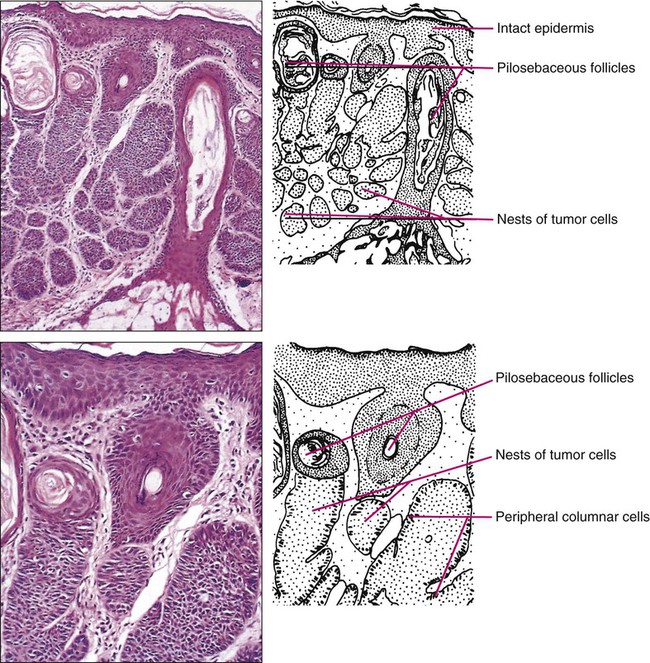

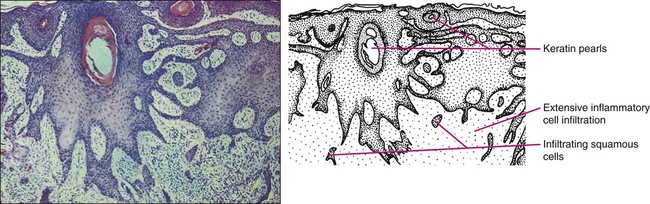

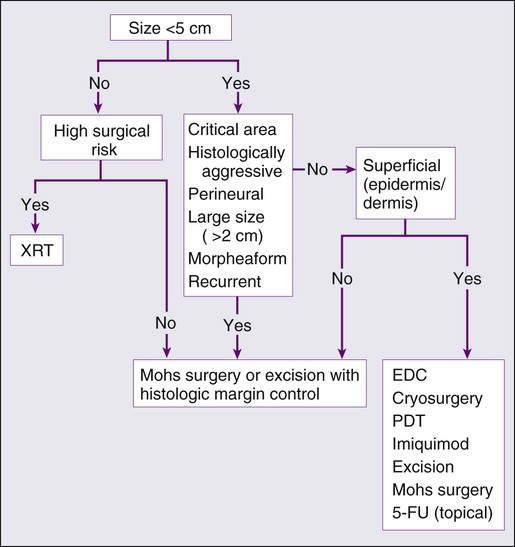

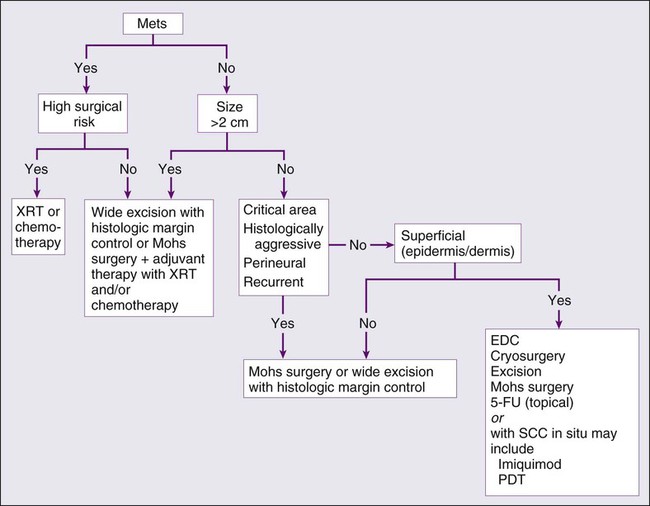

Gary S. Wood, Yaohui Gloria Xu, Juliet L. Aylward, Vladimir Spiegelman, Erin Vanness, Joyce M.C. Teng and Stephen N. Snow • More than 2 million new cases of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) occur annually in the United States, including 80% basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), 20% squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), and a few rarer types. • Incidence is increasing 2% to 3% per year. • Fifteen percent to 43% of solid organ transplant recipients will develop NMSC within 10 years. • Ultraviolet radiation from sun exposure is a major risk factor, causes mutations in key genes and explains the predilection of NMSC for sun-exposed skin. • Hedgehog signaling pathway mutations are involved in BCC pathogenesis. • p53 Mutations are involved in both SCC and BCC pathogenesis, as well as in the development of actinic keratoses, which are the precursors of SCCs. • There are several histopathologic subtypes of each NMSC. • The more infiltrative or poorly differentiated variants are more clinically aggressive (e.g., morpheaform BCC and spindle cell SCC). • TNM staging classifications exist for most types of NMSC and depend on clinical characteristics, pathological features and radiologic evaluation of the primary tumor, adjacent structures, lymph nodes, and viscera. • BCCs that are large, deep, or infiltrative may be locally aggressive and recurrent, but metastasize only rarely (<0.05%). • SCCs have a greater metastatic rate, especially those that are large, deep, have perineural invasion, or are located on the dorsal hands, lips, ears, penis, or sites of chronic infection, ulceration, or radiation. • Primary treatment for both BCCs and SCCs is surgical. Mohs surgery is preferred for ill-defined or aggressive lesions because it allows microscopic control of tumor margins. • The 5-year recurrence rate for BCC is 1% for Mohs surgery compared to 5% for other types of surgical excision. • Alternative primary therapies include various forms of physical destruction and radiation therapy. • Interferons and inducers of interferons (e.g., imiquimod) are useful in selected cases. Retinoids, hedgehog pathway agents, and difluoromethylornithine are other promising chemopreventive and adjunctive modalities. Locally Advanced and Metastatic Disease • Local recurrence is a problem for large, deep, or histologically infiltrative variants. SCCs with these features may also metastasize. The 5-year survival for patients with metastatic SCC is <50%. • The rarer forms of nonmelanoma skin cancer have a significantly more aggressive clinical course as compared with BCC and SCC. These include sebaceous carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), and cutaneous angiosarcoma. • Combinations of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy can be used for metastatic disease. • Palliation is directed mainly at managing complications such as local recurrence, destruction of adjacent structures, scarring, and loss of function. As in other malignancies, tumor suppressor genes and protooncogenes are two basic classes of genes that undergo mutations leading to skin cancer. The mutations in these genes lead to pathophysiologic changes, such as sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, and activating invasion and metastasis, described as hallmarks of cancer.1 Examples of tumor suppressor genes (whose loss of function contributes to tumor development) include the Patched (PTCH1 and PTCH2) genes involved in development of BCC, p53 involved in development of SCC, and the xeroderma pigmentosum genes involved in development of BCC, SCC, and melanoma.2–5 Protooncogenes are another class of genes whose mutations contribute to skin cancer formation. They become oncogenes after acquiring “gain-of-function” genetic alteration. These are generally growth-signaling molecules that once mutated can perpetually cause normal cells to become malignant cells by altering cellular growth. Some examples are the ras oncogene implicated in the development of SCC, and Smoothened (SMO) mutated in a subset of BCC.7–7 The role of the hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway has been well documented in vertebrate embryonic development, stem cell maintenance, and tumorigenesis (reviewed in references 8 and 9). Activation of the Hh signaling is a driving force in the development of both hereditary and sporadic cases of BCC. These tumors are the most common of all skin cancers, with an estimated 1 million new cases per year in the United States alone.10 Each of the three Hh genes—Sonic hedgehog (SHH), Desert hedgehog (DHH), Indian hedgehog (IHH)—encodes a secreted signaling peptide that binds to a membrane bound 12-span transmembrane receptor called Patched (PTCH1 or PTCH2). Binding of Hh ligand to the PTCH receptor on the target cell alleviates PTCH-mediated suppression of the 7-span transmembrane protein called Smoothened (SMO). SMO activation initiates an intracellular signal transduction cascade that ultimately activates the expression of Hh target genes. Transcriptional activation of Hh target genes in mammals occurs through the actions of three related proteins: GLI1, GLI2, and GLI3.11,12 GLI3 acts primarily as a transcriptional repressor,13 whereas GLI2 is reported to be the primary activator of Hh signaling, and GLI1 is a secondary target, downstream of GLI2, that also acts as a transcriptional activator.14 Aberrant regulation of the Hh pathway contributes to the development of many human cancers. Activating mutations of SMO or suppressing mutations of PTCH have been shown to constitutively activate the Hh signaling pathway (reviewed in reference 15). Involvement in human BCC was found through analysis of nevoid BCC kindreds (Gorlin syndrome, basal cell nevus syndrome).16 Persons with this autosomal dominant disease have odontogenic cysts, skeletal defects, palmar pits, various associated visceral tumors (medulloblastoma, meningioma, fibrosarcoma, cardiac fibroma, and ovarian fibroma), and multiple BCCs by a median age of 20 years. Early analyses mapped the defect to a tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 9q22–q31.17 This site proved to be the location of the PTCH1 gene. It was later elucidated that patients with nevoid BCC syndrome inherit one defective chromosome 9q region with loss of heterozygosity in the PTCH1 locus. Many BCCs from these patients show inactivation of the remaining PTCH1 gene through acquired somatic mutations, consistent with the view that the BCC phenotype develops once both alleles are nonfunctional. Thus, PTCH1 acts as a classic tumor suppressor gene in the skin. Mutations in PTCH1 also are common in many sporadic BCCs, as are mutations in other Hh pathway genes, including SMO, PTCH2, and SHH (reviewed in reference 18). The protein p53 is encoded by the TP53 gene on chromosome 17p and is an important regulator of cell cycle, DNA repair, and apoptosis.19 Inactivation of the p53 gene seems to play a principal role in the development of both premalignant actinic keratosis and SCC.20 SCC is the second most common skin cancer, accounting for approximately 200,000 cases per year and 2000 deaths per year.10 p53 mutations associated with SCC are usually UV induced, and many are pyrimidine alterations with CC to TT (cysteine to threonine) changes.21,22 Both the loss of the tumor suppressor ability of p53 and the ability of UV irradiation to affect induction of apoptosis by p53 are linked to SCC development.20 Mutations of TP53 have also been implicated in development of sporadic BCC.23 It seems that UV-induced alterations similar to those in SCC are involved in BCC induction. Many of the mutations are CC to TT or C to T alterations, consistent with UV damage. Mutations in the family of ras protooncogenes have been implicated in development of sporadic BCC, premalignant actinic keratosis, and sporadic SCC. They are among the most common mutations in human malignant disease.24 ras Proteins are small G-proteins responsible for transducing intracellular signaling. Activation of ras occurs only when guanosine triphosphate (GTP) is bound. The signal is attenuated by hydrolysis of GTP to guanosine diphosphate (GDP). Mutations in ras alter the rate of this hydrolysis, resulting in activated protein that constitutively activates tumor promoting Ras-Raf-MAP kinase and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways. XP is a collection of autosomal recessive disorders characterized by severe photosensitivity with the onset of cutaneous malignant lesions at a very early age. BCC, actinic keratosis, SCC, and melanoma develop during the first decade of life in persons without adequate photoprotection. Mutations in eight genes have been implicated in different XP phenotypes, which vary in severity of cutaneous neoplasia and frequency of neurologic delay.25 All XP-associated genes encode proteins that are part of a DNA repair process known as nucleotide excision repair, which responds to UV-induced DNA damage.4 These proteins recognize the damaged DNA, unwind the coiled DNA structure, and repair the damaged strand. Germline mutations in these genes result in defects in the repair process and their genomic caretaker role; however, actual tumor production is still caused by mutagenic inactivation of tumor suppressor genes such as TP53 and activation of oncogenes such as ras.26,27 Muir-Torre syndrome (MTS) is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by various sebaceous gland tumors and internal malignant lesions. The sebaceous gland tumors range from benign sebaceous adenoma to malignant sebaceous gland carcinoma, predominantly on the face. Keratoacanthoma is another cutaneous neoplasm of variable malignant potential that has been reported in as many as 20% of MTS patients.28 In initial studies of MTS families, investigators identified germline mutations in the human MSH2 gene.29,30 Subsequently, mutations in human MLH1 have also been identified in patients with MTS.31 It seems that, like other caretaker genes, human MSH2 and MLH1 encode a type of DNA-mismatch repair enzyme involved in repairing errors in DNA replication that occur naturally at a low rate. In cells that have this defect, the result is varying lengths of repetitive DNA sequences known as microsatellite instability.31 This microsatellite instability can result in functional gene mutations and has been observed in keratoacanthoma and sebaceous tumors from MTS patients.32 Dyskeratosis congenita is a progeroid disease associated with abnormalities in telomere function. The mutations in TERT, TERC, DKC1, TINF2, NHP2, TCAB1, and NOP10 may lead to shortening of telomeres resulting in premature aging, chromosomal rearrangements, and altered cell proliferation (reviewed in reference 33). The cutaneous SCC in dyskeratosis congenita patients were reported often when the patients were in their teens or twenties, with about half of the patients having SCC by the age of 50 years.34 This syndrome has a varied pattern of inheritance depending on the gene affected: DKC1—X-linked recessive; TERC and TINF2—autosomal dominant; NHP2, TCAB1 and NOP10—autosomal recessive; and TERT can be autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive. Fanconi anemia is associated with mutations in one of 15 genes involved in DNA cross-link repairs. This syndrome is characterized by early onset of a variety of hematologic and solid malignancies, including SCC.35,36 These patients have increased susceptibility to UV radiation (and other DNA–cross-linking agents), as the cells have altered ability to excise pyrimidine dimers.37 In the vast majority of cases of Fanconi anemia, there is an autosomal-recessive pattern of inheritance (with the exception of rare cases associated with mutations of FANCB where there is an X-linked recessive pattern). SCC is also a common feature in syndromes that are caused by structural abnormalities in skin, such as dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa with mutations in the gene encoding type VII collagen (COL7A1) that normally connect the basement membrane to the dermis,38,39 or junctional epidermolysis bullosa with mutations in genes encoding basic subunits of laminin 332 (LAMA3, LAMB3, and LAMC2), or COL7A1.40,41 Because melanin protects keratinocytes from UV radiation, the number of inherited disorders that affect melanin synthesis, melanosomal and lysosomal storage, and pigment granule transport are associated with predisposition to SCC. These syndromes are characterized by an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance and include oculocutaneous albinism that is usually associated with mutations in TYR, OCA2, or TYRP1 that affect melanin synthesis42,43; Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome characterized by abnormal melanosome and lysosome transport (mutations in HSP1, HSP3, HSP4, HSP5, HSP7, HSP8, and HSP9 genes)44; Chediak-Higashi syndrome, characterized by abnormal lysosome transport (mutations in LYST); Griscelli syndrome, characterized by abnormal pigment granule transport (mutations in MYO5A or RAB27A).45 In addition to mutations in the ras family described above, alterations in other genes involved in signal transduction were shown to play causative role in the development of SCC. Loss of function mutations in transforming growth factor-β receptor 1 (TGFBR1) are associated with multiple self-healing squamous epitheliomata (Ferguson-Smith syndrome),46 and mutations in EVER1 and EVER2 are associated with increased susceptibility to HPV types 5 and 8 in epidermodysplasia verruciformis.47 BCC accounts for approximately 80% of all skin cancers. The American Cancer Society reports more than 2 million cases of BCC and SCC yearly in the United States. Worldwide, the incidence for BCC varies widely, with the highest rates in Australia (>1000/100,000 person-years) and the lowest rates in parts of Africa (<1/100,000 person-years).48 In Australia, the annual incidence of BCC is slightly over 2% in males and 1% to 1.5% in females, while that of SCC is approximately 1% in males, and 0.5% to 0.8% in females (calculated from “Table 70-1. Age-Standardized Rates of NMSC in Whites per 100,000 Population from Australia, United States, and Europe [Selected Studies after 1990]” in reference 49).49 The incidence of BCC has increased over the past decades in a manner similar to the increase in melanoma. It is estimated that the incidence of NMSC is increasing 2% to 3% yearly.50 One study, conducted in New Hampshire, showed an annual increase in the incidence of SCC of approximately 10% and of BCC of approximately 5%.51 Exposure to ultraviolet radiation is the major risk factor for the development of BCC, especially severe sunburn during childhood and adolescence.52 Interestingly, the risk of BCC is significantly increased by recreational, intermittent intense exposure to the sun, whereas SCC appears to be strongly related to cumulative sun exposure.54–54 Other associated risk factors are Fitzpatrick skin types 1 and 2, red hair, freckling in childhood, family history of skin cancer, male sex, and Celtic ancestry.55 BCC is more common in lighter skinned African Americans than in darker persons.56 Immunodeficiency secondary to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or organ transplantation also is associated with increased risk of BCC.57,58 Other uncommon risk factors include exposure to arsenic,59 oral methoxsalen (psoralen) and UVA radiation,60 and ionizing radiation,61 especially among patients who have received radiation for acne. Keratin pattern and immunohistochemical results suggest the origin of BCC is the outer root sheath of the hair follicle below the isthmus.62 Recent work using genetic mouse models of BCC has shown that stem and progenitor cells are the most probable sources of BCC initiation.63 The locally invasive characteristic of BCC could be related to the presence of an abnormal hemidesmosome-anchoring fibril complex.64 Genetic abnormalities and mutations are thought to play a major role in development of BCC, especially in inherited syndromes of BCC. Patients with XP cannot repair the UV-induced DNA mutations; therefore, they are at increased risk of cutaneous carcinogenesis. Mutations in the Hh signaling pathway genes and TP53 are important in the pathogenesis of sporadic BCC and those arising in patients with the basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS) and XP.20,65–68 Patients need to be educated on self-skin examination and about protection against sun exposure. Photoprotection is essential to prevent NMSCs,69 and should begin at a young age to reduce the cumulative damage induced by the sun. Recently, chemopreventive agents for BCC have been explored, including retinoids,70 nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs,71,72 and difluoromethylornithine.73 Targeted skin-cancer screening of high risk populations is effective for early detection of BCC.74 In common nodular BCC, nodular masses of basaloid cells extend from the epidermis or outer root sheath into the dermis with surrounding connective tissue stroma (Fig. 70-1). A palisade arrangement of cells is present in the periphery. Sometimes as a result of tumor necrosis and disintegration, cystic spaces form. The surrounding stroma may retract from the tumor mass forming the typical lacunae, a sign that aids in diagnosis. In the pigmented type of BCC, large amounts of melanin are produced in the melanocytes that colonize the tumor. The many melanophages in the surrounding stroma also contribute to pigmentation. The superficial type of BCC shows multifocal small nests of basaloid tumor cells budding off the epidermis and adnexa. Morpheaform BCC is different in that strands of tumor cells are embedded in a dense fibrous tissue stroma. These strands often extend into the deeper dermis. Micronodular BCCs contain small nodules of tumor cells that invade surrounding stroma. The morpheaform and micronodular types are generally the most locally invasive variants of BCC. It is common for BCCs to show mixed histologic patterns of these various types. Even the less-invasive variants may invade deeply when located in regions of embryonic fusion planes, such as around the nose and ears. The most common location for BCC is the head and neck, especially the nose. BCC occurs on hair-bearing skin; mucosal surfaces are not involved. The major types of BCC include nodular, pigmented, superficial, and morpheaform. The typical nodular BCC is a dome-shaped, pearly papule with a telangiectatic surface and translucent rolled borders (Fig. 70-2). The surface might become ulcerated (Fig. 70-3). In darker-skinned individuals, especially African Americans, the more darkly pigmented BCCs may be misdiagnosed as seborrheic keratosis or nodular melanoma. Superficial BCC is a well-demarcated erythematous scaly plaque with elevated borders that often occurs on the trunk or extremities. It might be confused with Bowen disease or nummular eczema. The most difficult BCC to diagnose and manage is the morpheaform or sclerosing variant. This ill-defined, white, indurated plaque can be mistaken for a scar or localized patch of scleroderma, and therefore is ignored by patient and physician, with resulting wide subclinical extension. Patients with lesions clinically suspicious for BCC should undergo skin biopsy for histologic evaluation. Pertinent history is taken, such as the rate of growth, prior therapy, local neurologic symptoms, and evidence of immunosuppression, and a thorough skin examination is recommended. No formal staging system has been developed specifically for BCC, as metastasis of BCC is rare, with rates ranging from 0.003% to 0.55%.75 The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for non-eyelid skin cancer (Table 70-1) can be used for BCC as well as SCC. Regardless, it is important to stratify BCC into high-risk or low-risk lesions to guide treatment. Criteria for high-risk BCC include size greater than 2 cm, location in the midface (H zone) or ear, morpheaform or other aggressive histologic pattern, long duration, incomplete excision, perineural or perivascular involvement, and recurrent lesion.76 Table 70-1 TNM Staging System for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma From American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, Seventh Edition, 2010; and Farasat S, Yu SS, Neel VA, et al. A new American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: creation and rationale for inclusion of tumor (T) characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:1051-1059. Two-thirds of BCC recurrences occur during the first 3 years after treatment.77 The risk of development of another BCC is approximately 45% within 5 years.78 The risk of development of another NMSC is associated with the number of previous NMSCs. In an Australian study of patients with three to nine previous NMSCs, the risk of development of a new cancer was 93%.79 Patients treated for BCC need to be examined at least once a year for the first few years, preferably for 5 years after the last cancer was diagnosed. For patients with a history of multiple skin cancers, more frequent followup examinations are recommended. BCC is rarely metastatic but can be locally invasive (Fig. 70-4). Consequently, eradicating the primary tumor is the goal of therapy. Several treatment options are available, both surgical and nonsurgical. Selection depends on the tumor type, patient profile, size and location of tumor, recurrence, physician’s experience, and patient preference. Surgical modalities include Mohs micrographic surgery, surgical excision, cryosurgery, and electrodessication and curettage (EDC). Nonsurgical options include radiation therapy and photodynamic therapy.82–82 Other treatment modalities, such as immunotherapy with intralesional interferon83 and topical 5% imiquimod (Aldara),84 chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil,85 and retinoids,86 have been reported with variable success (Fig. 70-5). A systematic review of studies in which investigators reported recurrence rates of BCC after different treatment modalities showed that the mean 5-year recurrence rates after Mohs surgery and surgical excision were approximately 1% and 5.3%, respectively.87 High-risk BCC with increased risk for recurrence should be completely resected, preferably by Mohs technique or excision with margin control. Mohs surgery should be used in areas where preserving maximum tissue is important, such as eyelids, nose, and lips. It is also indicated for recurrent BCC and tumors with ill-defined clinical margins. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has developed its first appropriate use criteria (AUC) on Mohs micrographic surgery in collaboration with the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS), American Society for Mohs Surgery (ASMS), and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS). The Mohs AUC was recently published in journal of the American Academy of Dermatology88 and Dermatologic Surgery.89 If simple excision is used, the margin for excision, according to the newest National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, should be at least 4 mm for low-risk tumors, and 10 mm for high-risk tumors. If there are contraindications to surgery, or a low-risk tumor that is small and located on less-critical sites, such as the trunk, cryotherapy or EDC can be used with good outcome. Because of the less-favorable long-term cosmetic results and the possibility of secondary radiation-induced skin cancer, radiation therapy is best avoided in the care of relatively young patients. Very large or poorly controlled BCC may necessitate a coordinated approach of standard surgical excision, Mohs surgery, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy or chemotherapy.90 Targeted therapy suppressing the Hh signaling pathway at the level of SMO, or at the final effectors, GLI transcription factors, has been proven effective. GDC-0449 (Vismodegib), a synthetic oral inhibitor of SMO, is the first FDA-approved drug in this category. GDC-0449 is indicated for adults with metastatic BCC, or with locally advanced BCC that has recurred following surgery or who are not candidates for surgery, and who are not candidates for radiation.63,91 Other potential new BCC therapies include vitamin D3, which works through blocking Hh signaling, topical treatment with the RARB/RARG-selective retinoid, tazarotene,63 and molecules targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway.92 It remains to be determined whether the strategy of inhibiting Hh signaling will truly result in the eradication of BCC and why certain tumors are refractory to such treatment.63 There are many risk factors for SCC, the most important being solar radiation. The incidence of SCC is increasing especially on the head and neck area as a result of exposure to sunlight.94 SCC is thought to be correlated with recent (in the 10 years preceding diagnosis) chronic sunlight exposure95 and cumulative sun exposure.96 Phototherapy with PUVA (psoralen + ultraviolet A) increases the risk of SCC. Other risk factors for SCC include fair skin, red hair, albinism, and Celtic origin. Nonsolar risk factors include exposure to chemicals (insecticides and herbicides),97 arsenic, organic hydrocarbons, chronic thermal injury and scars, ionizing radiation, and chronic immunosuppression.98 The incidence of SCC is increased by 65 times in organ transplant patients, as compared to the tenfold increase of BCC.99 This increase of risk is correlated with the type of organ transplantation and elapsed time after transplantation. Heart and lung transplant recipients have a higher risk of NMSC than kidney transplant recipients, possibly because of more intense immunosuppression.99,100 SCCs in organ transplant patients are usually more aggressive, with an increased risk of metastases of approximately 8%, as compared to the risk of 0.5% to 5% in the general population.101 Tobacco is a risk factor for oral SCC. Viruses, especially human papillomavirus (HPV), have been linked to epithelial malignancies, including SCC. This is especially true among patients with epidermodysplasia verruciformis, who have an underlying immunodeficiency and can develop SCCs within HPV-infected warts.98 Carcinogens, such as ultraviolet radiation (UVR), certain chemicals, and viruses play a role in the pathogenesis of SCC by damaging keratinocyte DNA and other cellular contents. It is known that UVR, especially UVB, causes mutations in DNA of keratinocytes.102 Early repair of these mutations is important for the prevention of SCC. Patients with NMSC are thought to have decreased ability for DNA repair compared with controls, thus making them more susceptible to the effects of UVR.103 One example is the effect of UVR on DNA alterations in patients with XP who are genetically unable to repair these defects. UVR also causes cutaneous immunosuppression, weakening the host’s immune response against tumor cells and promoting tumor growth.104 Studies of SCCs have shown that mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene are an early event.3,105 Most of the mutations occur at dipyrimidine sequences, in the form of UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.106 The development of SCC does not occur by a simple single step, but rather through a multistage process. Conversion of susceptible keratinocytes to premalignant cells and then progression to carcinoma occurs as a result of successive genetic hits.107 In the initiation stage of carcinogenesis, there is clonal expansion of premalignant cells. The next stage is increased proliferation of premalignant cells and subsequent chromosomal aberrations. The final stage is conversion to SCC. DNA aneuploidy with a single peak was detected by flow cytometry in lesions of Bowen disease, suggesting a monoclonal proliferation of abnormal keratinocytes and a clonal basis for skin cancer.108 Aberrant expression of P-cadherin, and changes in expressions of cytokeratins and transforming growth factors, all play a role in tumor progression.109 Prevention of SCC is similar to that of BCC, that is, an emphasis on photoprotection is essential. Interestingly, one study showed that regular application of sunscreen has prolonged preventive effects on SCC but with no statistically significant benefit in reducing BCC.110 Treatment of precursor actinic keratoses with field therapy such as photodynamic therapy, topical 5- fluorouracil and imiquimod cream may reduce the number of lesions transformed into SCC. Promising chemopreventive agents for lesions in the actinic keratosis–SCC spectrum include retinoids, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, difluoromethylornithine, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a green tea catechin.111 In organ transplant recipients, systemic retinoids and reduction of immunosuppression are used as preventative means in reducing the incidence of NMSCs.100 One study showed that high-dose topical tretinoin, however, is ineffective at reducing risk of NMSCs in high-risk patients.70 A deep shave or punch biopsy that includes the base of the tumor is needed to distinguish SCC in situ from invasive SCC. Bowen disease is SCC in situ. The stratum corneum is thickened, and epidermis is hyperplastic with disordered maturation of keratinocytes. Mitotic figures, multinucleated keratinocytes, and dyskeratotic cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm are seen in the epidermis. Atypical cells can invade follicular and ductal structures. The histology of invasive SCC shows masses of epidermal cells proliferating into the dermis. Atypical squamous cells and mitotic figures are seen (Fig. 70-6). The cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei. Horn pearls, which are a result of keratinization of squamous cells, are seen. The dermis may show a marked inflammatory reaction. Spindle cell SCC is a rare variant composed of mainly spindle cells, but some squamous differentiation may be seen. Spindle cells have large vesicular nuclei and scant cytoplasm and intermingle with the collagenous stroma. Spindle cell SCC is poorly differentiated with numerous mitoses and deep invasion and requires immunohistochemistry to differentiate it from other spindle cell tumors. Another uncommon histologic variant of SCC is the acantholytic or adenoid SCC, seen more on the face and neck. There are nests of tumor cells with dyskeratotic cells and central acantholysis forming pseudoglandular structures. SCC occurs more on the head and neck area in whites, but in blacks there is no predilection for sun-exposed areas of the body.112 SCC in situ can arise de novo or from premalignant lesions, such as actinic keratosis or arsenical keratosis. In fact, in whites, the majority of SCCs arise from actinic keratoses. These can eventually spread beyond the epidermis and become invasive. Bowen disease is a SCC in situ arising de novo. If Bowen disease occurs on the glans penis or rarely vulva it is referred as erythroplasia of Queyrat. Bowen disease often appears as a well-defined single red plaque with dry surface scaling. Lesions are slow growing and asymptomatic, thus ignored by many patients. The physician might initially treat it as psoriasis or nummular eczema with no response. There is a 3% to 5% chance that Bowen disease can progress into invasive SCC.113 Clinically erythroplasia of Queyrat resembles Bowen disease, but lacks the dry superficial scale. Instead, the surface is moist and smooth. Invasive SCC can also arise from normal skin. It starts as a small, firm, dull-red nodule, which can undergo central ulceration. Sometimes if SCC arises from solar keratosis an adherent keratotic scale can be seen. If ignored, the lesion grows horizontally and vertically and may become fixed to the underlying tissue. The surface might become ulcerated with bleeding, malodorous exudate, or crust. The borders are usually elevated and firm. Occasionally a fungoid lesion without ulceration can be seen. SCC of the lower lip often arises from previously solar-damaged areas (actinic cheilitis). Initially local thickening of the vermilion border occurs that then progresses into a noduloulcerative lesion (Fig. 70-7). Persistent subungual erythema with pain and swelling should alert the physician for SCC of the nail region. This form of SCC may be confused with warts (Fig. 70-8). As mentioned earlier, SCCs can arise from chronic sinuses, scars, and chronic thermal damage. The risk of metastasis of SCC is variable, depending on the site and tumor characteristics. The deeper and larger the tumor, the higher is the chance of metastasis. Recurrent tumors are at high risk for metastasis. Lesions with perineural involvement have a 35% metastatic rate.114 Among the different histologic types, desmoplastic SCCs are more likely to metastasize.115 The risk of metastasis of SCC derived from actinic keratosis is low (0.5% to 3.7%) compared with SCC arising in radiation-induced SCC and chronic osteomyelitis (20% and 31%, respectively).118–118 High-risk areas for metastasis include tumors arising from the dorsal hands, lips, ears, and penis. For example, SCC of the lower lip has a 15% risk of metastasis.119 Bowen disease and erythroplasia of Queyrat have a low chance of metastasis, but once they become invasive, the risk of metastasis increases significantly. Evaluation for patients with SCC is similar to that of BCC, and stratification of SCC into high-risk or low-risk tumors is practical to guide treatment. However, physicians must be reminded that SCCs in general have a greater potential for recurrence and metastasis than BCCs. The first step is to estimate the peripheral and vertical extension of tumor cells. The new seventh edition of the AJCC staging system for noneyelid skin cancer, including cutaneous SCC, incorporates tumor-specific (T) staging features, such as thickness greater than 2 mm, Clark level greater than IV, perineural invasion, anatomic site, and degree of histologic differentiation (see Table 70-1).120,121 Other reported high-risk features that may result in local and distant metastasis are size greater than 2 cm, recurrent status, and immunocompromised host.122 Next, the patient should be evaluated for metastasis to the lymph nodes and other organs. Note that eyelid skin cancers are staged differently, using a separate system that is described in the section on sebaceous carcinoma. For SCC patients, closer followup intervals are recommended, such as every 3 to 6 months for the first several years, depending on the location, size, aggressiveness, and node status of the primary tumor. The exception would be small SCCs arising from actinic keratoses on sun-exposed surfaces, where the rate of metastasis is very small (0.5%). In these patients, routine followup every 6 to 12 months is all that is required. The treatment options for SCC are similar to BCC treatment, with some differences (Fig. 70-9). Destructive methods or surgical excision can treat Bowen disease effectively. When cancer cells invade hair follicles or ducts, treatment by excision is preferred. Small uncomplicated SCCs (<1 cm) in low-risk locations are frequently treated with EDC. Cryotherapy is an alternative treatment. Simple surgical excision with margin control is commonly used for smaller tumors and those on the trunk and extremities. According to the newest NCCN guidelines, the recommended margin for low-risk SCC is 4 to 6 mm, and for high-risk tumor is 10 mm, if possible.123 The excision should include the subcutaneous fat. Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice for high-risk SCCs and for tissue preservation where tissue sparing is cosmetically or functionally vital.124 Radiation can also be used as a primary choice of treatment in the elderly at high risk for surgical complications or patients with contraindications to anesthesia or surgery. Radiation can be useful to treat tumors on the eyelids, nose, ears, and lips when surgery is not practical. The disadvantages are the cost, blind margin control, and prolonged treatment duration. The cure rate for tumors larger than 2 cm is 85% to 95%.125 Radiation therapy is best avoided in treating verrucous carcinomas and younger patients because of poor long-term cosmetic results. SCCs that have arisen from ulcers, scars, and irradiated sites are better removed by margin-controlled surgery than by radiation therapy. Aggressive or deeply invasive SCCs are treated with deep surgical excision with margin control when practical. Mohs surgery may be helpful in delineating critical areas in massive tumors or tumors with ill-defined borders. SCC invading surrounding structures such as bone and cartilage must also be excised. Tumors with neural or perineural involvement that are at high risk of recurrence should be completely excised preferably with the Mohs technique. High-risk tumors may require adjuvant therapy with radiation therapy126 or chemotherapy.127,128 A recent review article summarized treatment modalities for locally advanced nonmetastatic cutaneous SCC.129 Commonly used traditional chemotherapy includes oral capecitabine and intravenous platinum-based regimens. Biological response modifiers refer to agents that augment host antitumor immune responses, examples of which include oral isotretinoin and interferons. Because in vitro studies demonstrated synergism between retinoids and interferons, these agents have been used in combination with success.130,131 Newer targeted agents are promising, including epidermal growth factor receptor antagonists, small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and proteasome inhibitors. Sentinel lymph node biopsy may be considered in patients with high-risk SCC.132,133 If lymph node metastasis has occurred, treatment is wide surgical resection of tumor with regional lymph node dissection with or without adjunctive radiation. However, elective lymph node dissection is not commonly performed in the absence of evidence for regional spread. Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are common cutaneous neoplasms that are thought to derive from the infundibular portion of hair follicles. They most often present as solitary rapidly growing, pink or flesh-colored, dome-shaped or crateriform nodules. They occur most commonly on sun-exposed areas in fair-skinned elderly individuals.134 Clinically, KAs are characterized by their spontaneous involution over several months with residual atrophic scarring and local tissue destruction.135 Although most cases of KA are solitary, subsets of individuals with multiple KAs have been described. These include the familial Ferguson-Smith type, comprising multiple KAs at an early age, and the generalized eruption of thousands of small KAs as described by Grzybowski.136 KAs frequently occur in individuals with MTS, XP, and solid-organ transplantation.137 They also occur in areas of scarring from prior trauma, thermal burns, and surgical treatment, and in association with many benign conditions such as stasis dermatitis, lichen planus, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, and discoid lupus erythematosus.134 Debate exists as to whether KAs are a distinct clinical entity or a subtype of well-differentiated SCC. Significant efforts have been made to find practical, reliable criteria to distinguish KA from SCC.138,139 Similarities include expression of oncogenetic and cell cycle–regulating proteins including p53; a subset of these tumors also share trisomy 7 anomaly.140–143 On the other hand, studies on apoptotic marker P2X7, on antiapoptotic Bcl-xL protein, on loss of heterozygosity, on expression of angiotensin type 1 receptor and of desmogleins 1 and 2, on adhesion molecules vascular cellular adhesion molecule and intercellular adhesion molecule, on telomerase activity, and on chromosomal aberrations assessed by comparative genomic hybridization suggest that KA and SCC possess distinct genetic aberrations that result in separate developmental pathways.144–152 One study localized recurrent aberrations to chromosomes 17, 19, 20, and X in one-third of the KAs studied. Recurrent aberrations on chromosomes 7, 8, 10, and 13 were characteristic of SCC, not of KA, perhaps accounting for the progressive growth and lack of regression of SCC.153 Microsatellite instability and loss of heterozygosity are seen uncommonly in KA unless associated with MTS. Because UV exposure is a key component of etiology, sun-protective clothing, sunblock use, and avoidance of UV exposure are the primary means of prevention. Timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment of chronic scarring conditions could reduce incidence in the affected population. Self skin-examination or examination by a dermatologist to identify the characteristic lesion is the only means of early detection.135 Histologically, a mature KA has a distinctive architecture characterized by a keratin-filled crater lined by a proliferating squamous epithelium with abundant pale eosinophilic “glassy” cytoplasm, epithelial lipping, and multiple keratin horn pearls with central orthokeratosis. Cytology is often indistinguishable from that of a well-differentiated cystic SCC. At the base of the tumor, islands and strands of atypical cells may invade the dermis. Frequently there is a heavy inflammatory infiltrate at the base of the lesion comprising lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils. Atypical mitoses, as well as perineural and perivascular invasion, also may be present, particularly in tumors involving the head and neck.154,155 Patients will usually describe rapid onset and growth of a firm nodule with central depression filled with keratinous crustlike material over sun-exposed sites. The lesion will involute spontaneously leaving an atrophic scar over the course of several weeks. If evaluated early, a biopsy extending into the dermis is warranted to secure the diagnosis and to assess for SCC. Palpation of regional lymph nodes is indicated if there is suspicion for SCC, a cutaneous carcinoma known to metastasize.134 Although not thought to metastasize in general, several cases of highly aggressive and metastatic KAs have been reported, leaving some to question whether these were truly KAs or rather KA-like SCCs.136 However, given reported cases of local destruction and metastatic disease, it is recommended that KAs be treated in the same manner as SCCs. Complete conservative excision or Mohs micrographic surgery is the mainstay of therapy.156 Radiotherapy, photodynamic therapy, electrodessication and curettage, systemic immunosuppressive medications, systemic retinoids, and topical and intralesional immunosuppressive and immunomodulating modalities have been reported with varying success.157–163 Patients receiving chronic immunosuppression are at significantly increased risk for development of NMSC. Additionally, they are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality as a result of development of multiple primary tumors and more aggressive subtypes of skin carcinoma. Although increased risk is associated with immunosuppression intended to treat many ailments, studies of solid organ transplant recipients offer the clearest data at this time. As available immunosuppressive drugs and care for the chronically immunosuppressed population improve, the longevity of this population also is increasing. With increased longevity, the burden of NMSC in this group has grown significantly.164 Reports on the incidence of NMSC varies in organ transplant populations studied from different parts of the world and also varies with the specific transplanted organ. Within 10 years from solid organ transplantation, 15% to 43% of recipients will develop NMSC. The highest risk is associated with heart and lung transplantation, the next with kidney transplantation, and the least with liver transplantation.164 This corresponds to the overall degree of immunosuppression required to prevent rejection of the specific organ in each population. The most significant risk factors for the development of NMSC in organ transplant recipients include advanced age, cumulative UV exposure pretransplantation, degree and duration of immunosuppression, fair skin type, diagnosis of NMSC prior to transplantation, pretransplantation disease requiring prior immunosuppression (e.g., systemic lupus), and diagnosis of lymphoma before or after transplantation.99,165 In addition to the organ transplant population, there is mounting evidence for concern regarding increased risk of NMSC in other immunosuppressed populations. There is significantly increased risk for patients with rheumatologic disease and psoriasis receiving tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, methotrexate and prednisone.166,167 Immune dysregulation from chronic lymphocytic leukemia elevates risk of aggressive SCC and subsequent mortality.168 Highly active antiretroviral therapy has dramatically increased the longevity of the HIV-infected populations and with that has evolved a significant increase in BCCs and SCCs.169 The use of thiopurines to treat inflammatory bowel disease has been shown to substantially increase the risk of SCC development.170 Appropriate dermatologic care for organ transplant recipients (and presumably others with significant chronic immunosuppression, although these guidelines are less-well established) should be based on risk stratification. All individuals should receive baseline screening and risk assessment by a dermatologist and education regarding skin cancer risk, photoprotection, and self-screening. Many transplantation centers have dermatologists with specific expertise in the care of these patients. Those determined to be at increased risk should be screened every 6 to 12 months, or more frequently if they develop multiple or aggressive skin cancers.99 Treatment of NMSC in organ transplant recipients and similarly immunosuppressed patients should be tailored to the individual’s needs. Standard modalities, including excision, electrodessication and curettage, curettage and cryotherapy, and Mohs micrographic surgery, are appropriate in most cases. Aggressive treatment of precancerous lesions with standard modalities, such as cryotherapy, topical retinoids, imiquimod, topical 5-fluorouracil, and photodynamic therapy, is beneficial. Patients with extensive photodamage amounting to areas of “field cancerization” should be identified and treated aggressively with standard modalities, then monitored closely to reduce the risk of developing numerous or aggressive tumors in these areas.100 Organ transplant recipients developing multiple new primary skin cancers (5 to 10 per year) or skin cancers with aggressive histologic subtypes despite appropriate monitoring and therapy are candidates for chemopreventive therapy. Acitretin can be used at doses from 10 to 25 mg daily with significant reduction in the number of new NMSC for many patients. Dosage is limited by side effects. Liver function, kidney function, and blood lipids must be monitored while on therapy. The chemopreventive effect of acitretin lasts only for the duration of therapy, and a rebound of SCC may occur upon discontinuation of acitretin.99,100 Revision of immunosuppression may be appropriate for patients who develop multiple or histologically aggressive NMSC. Consultation should take place between the patient and the patient’s transplant physicians regarding possible reduction of current medication or a switch to a comparable immunosuppressive agent with a better side-effect profile for skin cancer. When graft function is stable and surgical wounds have healed, sirolimus or everolimus may be considered for their antineoplastic properties. Sirolimus is associated with a significant reduction in malignancies posttransplantation. Azathioprine should be discontinued if possible because of its photocarcinogenic properties. Tacrolimus is preferable to cyclosporine as a first-line calcineurin inhibitor because of an associated lower risk of NMSC. Although triple-drug immunosuppressive therapy remains the standard treatment after organ transplantation at most centers, dual therapy and calcineurin inhibitor monotherapy have been shown to reduce NMSC without significant increase in organ rejection in patients more than 6 years posttransplantation.165 Patients with aggressive, large, recurrent, numerous or metastatic NMSC should be referred to a provider with expertise in the evaluation of their metastatic potential and management. A role for sentinel lymph node biopsy has been established in select aggressive SCC. Adjuvant radiation therapy is helpful in selected cases of SCC or BCC that are aggressive or have high-risk features. Involvement of a multidisciplinary transplant team that includes transplant physicians, dermatologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, otorhinolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons, may benefit those patients who are extensively afflicted with NMSC.165 Current efforts to improve outcomes for organ transplant recipients with nonmelanoma skin cancers are centered on modification of current immunosuppressive regimens and adaptation of immunosuppressive regimens using newer agents with more favorable side-effect profiles regarding skin cancer development, such as sirolimus and everolimus. Transplantation centers continue to investigate regimens that minimize immunosuppression at induction and later in the course of transplantation for appropriate patient candidates. For example, calcineurin monotherapy (compared to two- or three-agent regimens) was associated with a higher graft survival rate and a lower skin cancer rate in selected patients 6 to 12 years posttransplantation.171 Ongoing studies are needed to further understand appropriate strategies for optimization of graft survival weighed against the risk of carcinogenesis. Sebaceous carcinoma is a rare, potentially devastating tumor that derives from the adnexal epithelium of sebaceous glands. Principally, the tumor occurs in two different clinical scenarios: ocular sebaceous carcinoma (OSC) and extraocular sebaceous carcinoma (ESC).172,173 OSC accounts for 0.2% to 0.8% of all eyelid tumors and 1% to 1.5% of all malignant tumors of the eyelid.174 OSC affects women 1.5 times more frequently than men; however, a slight male preponderance occurs in cases of ESC.175–179 The mean age at diagnosis is 65 years (range: 40 to 60 years), but OSC has been reported in adults in their nineties and in a 3-year-old child. Sebaceous carcinoma seems to have a higher incidence in the Asian population.180–183 This tumor is associated with MTS, an autosomal-dominant disorder of mismatch repair genes characterized by sebaceous tumors (benign and malignant), as well as other visceral malignant tumors.184 Although sebaceous carcinoma with microsatellite instability has been found in several renal organ transplant recipients,184 only a subset of these tumors possess microsatellite instability. Mutations in p53 are significantly associated with sebaceous carcinoma and are independent of microsatellite instability, therefore suggesting a divergence in molecular pathogenesis.185 Epigenetic inactivation of E-cadherin, leading to loss of the membrane bound molecule, is associated with reduced disease-free survival in OSC.186 There is evidence that the chronic inflammation caused by chalazion may be causative in OSC. The unsaturated 8-carbon fatty acid oleic acid has been shown to cause dysplasia in glandular structures.172 Risk factors associated with poor prognosis include duration longer than 6 months; vascular or lymphatic involvement; orbital extension; poorly differentiated tumor morphology; multicentricity; pagetoid spread into the conjunctival epithelium, cornea, or skin; upper and lower lid involvement; and history of radiation exposure.180,187–189 In the past, 14% to 25% of patients reportedly had metastasis, most frequently involving regional nodal basins, followed by spread to the liver, lung, brain, and bones.175,177–180

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers

Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Genetics of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

Fundamental Science and Clinical Relevance

Hedgehog Signaling Pathway

p53 Mutations

ras Mutations

Mutations of Other Genes Predisposing to Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Epidemiology

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

Prevention and Early Detection

Pathology and Pathways of Spread

Clinical Manifestations/Patient Evaluation/Staging

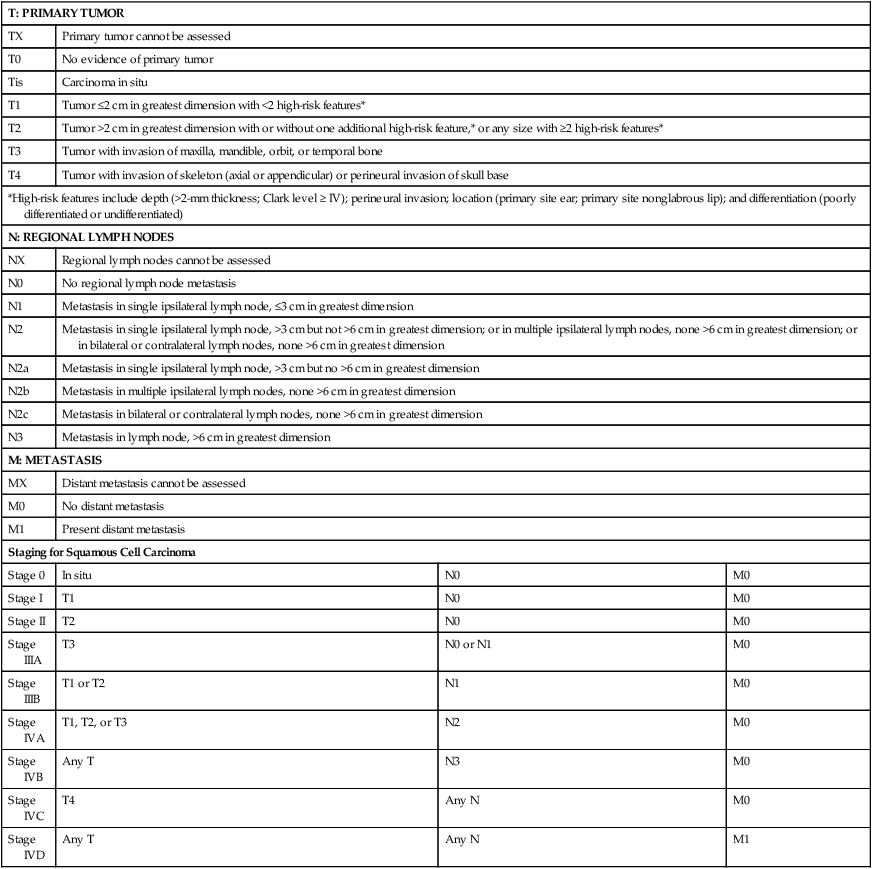

T: PRIMARY TUMOR

TX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

Tis

Carcinoma in situ

T1

Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension with <2 high-risk features*

T2

Tumor >2 cm in greatest dimension with or without one additional high-risk feature,* or any size with ≥2 high-risk features*

T3

Tumor with invasion of maxilla, mandible, orbit, or temporal bone

T4

Tumor with invasion of skeleton (axial or appendicular) or perineural invasion of skull base

*High-risk features include depth (>2-mm thickness; Clark level ≥ IV); perineural invasion; location (primary site ear; primary site nonglabrous lip); and differentiation (poorly differentiated or undifferentiated)

N: REGIONAL LYMPH NODES

NX

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0

No regional lymph node metastasis

N1

Metastasis in single ipsilateral lymph node, ≤3 cm in greatest dimension

N2

Metastasis in single ipsilateral lymph node, >3 cm but not >6 cm in greatest dimension; or in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension; or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension

N2a

Metastasis in single ipsilateral lymph node, >3 cm but no >6 cm in greatest dimension

N2b

Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension

N2c

Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension

N3

Metastasis in lymph node, >6 cm in greatest dimension

M: METASTASIS

MX

Distant metastasis cannot be assessed

M0

No distant metastasis

M1

Present distant metastasis

Staging for Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Stage 0

In situ

N0

M0

Stage I

T1

N0

M0

Stage II

T2

N0

M0

Stage IIIA

T3

N0 or N1

M0

Stage IIIB

T1 or T2

N1

M0

Stage IVA

T1, T2, or T3

N2

M0

Stage IVB

Any T

N3

M0

Stage IVC

T4

Any N

M0

Stage IVD

Any T

Any N

M1

Primary Therapy

Treatment of Locally Advanced and Metastatic Disease

Controversies/Problems/Challenges/Future Possibilities and Clinical Trials

Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Bowen Disease

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

Prevention and Early Detection

Pathology and Pathways of Spread

Clinical Manifestations/Patient Evaluation/Staging

Primary Therapy

Treatment of Locally Advanced and Metastatic Disease

Keratoacanthoma

Epidemiology

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

Prevention and Early Detection

Pathology and Pathways of Spread

Clinical Manifestations/Patient Evaluation/Staging

Primary Therapy

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer in Immunocompromised Hosts

Epidemiology

Prevention and Early Detection

Primary Therapy

Locally Advanced Disease and Palliation

Treatment of Metastatic Disease

Future Possibilities and Clinical Trials

Sebaceous Carcinoma

Epidemiology

Etiology and Biological Characteristics

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers: Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Carcinomas