Fig. 2.1

A superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with a characteristic raised, “pearly” appearance is depicted (a, yellow circle, c). A locally advanced infiltrative BCC is shown on the left shoulder/neck area (b). While this advanced lesion has low metastatic potential, it was infiltrative into the underlying muscle and along the spinal accessory nerve

Table 2.1

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas (7th edition)

Primary tumor (T)* | |

|---|---|

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

T1 | Tumor ≤ 2 cm in greatest dimension with less than two high-risk features** |

T2 | Tumor > 2 cm in greatest dimension or tumor any size with two or more high-risk features** |

T3 | Tumor with invasion of maxilla, mandible, orbit, or temporal bone |

T4 | Tumor with invasion of skeleton (axial or appendicular) or perineural invasion of skull base |

* Excludes cSCC of the eyelid | |

* High-risk features for the primary tumor (T) staging | |

Depth/invasion | >2 mm thickness |

Clark level ≥ IV | |

Perineural invasion | |

Anatomic location | Primary site ear |

Primary site hair-bearing lip | |

Differentiation | Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated |

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

|---|---|

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph nodes metastases |

N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, ≤3 cm in greatest dimension |

N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, >3 cm ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none > 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none > 6 cm in greatest diameter |

N2a | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, >3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N2b | Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none > 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N2c | Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none > 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node, >6 cm in greatest dimension |

Distant metastasis (M) | |

|---|---|

M0 | No distant metastasis |

M1 | Distant metastasis |

Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Group | T | N | M |

Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

Stage II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

Stage III | T3 | N0 | M0 |

T1-T3 | N1 | M0 | |

Stage IV | T1-T3 | N2 | M0 |

Any T | N3 | M0 | |

T4 | Any N | M0 | |

Any T | Any N | M1 | |

Surgical Considerations

A detailed clinical examination is paramount, and most BCC can be diagnosed by their appearance. A skin biopsy is usually performed to provide histologic confirmation of the diagnosis. Shave biopsies, punch biopsies, and excisional biopsies can be used for the diagnosis of BCC.

Surgical options for BCCs at low risk for recurrence include conventional surgical excision, Mohs surgery, and electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C). Typically, surgical excision of the BCC is the preferred option and can often be performed under local anesthesia. Generally, surgical excision of the trunk, extremity, or small facial BCCs of the head or neck with anywhere from 1 to 10 mm margins has been associated with 5-year cure rates exceeding 95 %; therefore, 3–5 mm surgical margins are commonly used for the excision of these lesions [8]. Infiltrative/morpheaform lesions may require wider (5–10 mm) margins due to their indistinct borders. Mohs surgery is usually reserved for lesions that exhibit features associated with an increased risk for recurrence and for locations in which tissue sparing is of great value due to cosmetic or functional concerns. When standard surgical excision is performed, all extremity lesions should be removed in a longitudinal fashion. While a longitudinal incision of the extremity may not be the most cosmetic, it allows for an easier re-excision if the lesion recurs and also disrupts less lymphatic tissue so that lymphedema is minimized (See Chap. 1, Fig. 2.2). The concept of longitudinal excisions of the extremities is critical for all NMSCs and should be considered the standard. Cryosurgery may be used for small superficial lesions, but for larger nodules, its use is infrequent. With proper lesion selection and operator skill/experience, ED&C is capable of achieving a high cure rate.

Fig. 2.2

A superficial squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is noted with a typical raised, scaly/crusty appearance (a, yellow circle) in the background of multiple actinic keratosis (scaly, red patches) or possibly SCC in situ. An advanced SCC of the left hand/forearm demonstrated rapid growth and nodal and visceral metastases (b). This local disease was not responsive to systemic treatment, and despite the presence of metastatic disease, surgery was required in the form of an amputation for palliation of pain, bleeding, and infection. (c) A neglected SCC of the right scalp was completely excised with clear margins (c: Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

Other Treatments

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a nonsurgical treatment option for superficial BCCs. The three components of PDT are a light source; exogenous photosensitizer, such as aminolevulinic acid or methyl-aminolevulinic acid; and oxygen. Excellent response rates have been reported for this modality in selected BCC.

The superficial nature of early BCCs allows for effective topical treatments of these lesions. Options for topical therapy include 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and imiquimod. 5-FU is a pyrimidine analogue that induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Extensive experience with topical 5-FU indicates that this treatment should be restricted to superficial BCCs in non-critical locations. Imiquimod 5 % cream is an immune response modifier that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of superficial BCCs in low-risk sites. Topical agents require active patient participation and close practitioner surveillance to prevent BCC progression and/or recurrence. All nonresponding lesions should be biopsied for persistent or recurrent disease. Radiation therapy (RT) is utilized as a primary modality in patients who are poor surgical candidates. As an adjuvant therapy, radiation therapy can achieve good results with excellent cosmetic results if applied appropriately especially in patients with high risk of recurrence. A randomized study in 347 patients receiving either surgery or RT as primary treatment of BCC found RT to result in higher recurrence rates than surgery alone (7.5 % vs 0.7 %) [9]. For multiple recurrent BCC that have failed to be cleared by surgical excisions, RT is often a useful option, particularly for microscopically involved margins.

Advances in the understanding of the molecular mechanisms that lead to BCC formation has led to the FDA recently approving a novel agent Vismodegib, a first-in-class Hedgehog pathway inhibitor. This agent can be used for refractory locally advanced BCCs that have failed all other options or for the rare metastatic BCC patient. While this treatment is currently quite expensive, the results can be significant in clearing the tumors. Multiple side effects have been reported with this agent which may limit its use in certain patients.

Close follow-up is required following treatment to diagnose both local recurrences and new skin cancers and to assess posttreatment outcomes. Most dermatologists recommend reevaluation every 3–6 months for the first year following treatment and then every 6–12 months thereafter. About 30–50 % of patients may develop another NMSC within 5 years. Therefore, close skin surveillance is mandatory.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common type of NMSC, accounting for approximately 20 % of all NMSC cases. SCCs can arise de novo, but unlike BCCs, SCCs often arise from precursor lesions that show partial-thickness epidermal dysplasia, such as actinic keratosis (AK). AK presents as slightly scaly papules with ill-defined borders, on sun-exposed skin. Seborrheic keratosis is tan to dark brown stuck-on appearing benign, warty growths located anywhere on the body. The rate of malignant transformation from AK to SCC is estimated to range from 0.025 % to 16 % per year for an individual lesion [10]. Intraepithelial SCC or carcinoma in situ is believed to be the next step in the progression to invasive SCC. Risk factors for developing SCC include sun exposure, radiation, chronic inflammation, immunosuppression, and virally induced.

SCC typically develops on areas that are commonly exposed to the sun, including the head and neck, scalp, face, dorsum of hand, shoulder, and chest. The majority of these lesions occur on the head and neck areas. SCCs appear as ill-defined keratotic papules and nodules which may be ulcerated. They can be reddish brown, erythematous, or flesh colored. Occasionally, cutaneous horns from hyperkeratosis may be seen, and bleeding can occur with SCC. A typical SCC in the background of extensive AK is compared to a locally advanced SCC as depicted in Fig. 2.2a, b. Histologically, they show nests of atypical keratinocytes with dermal invasion. In situ lesions, also known as Bowen’s disease, are characterized by full-thickness atypical epidermal involvement. Histologic grading is divided into well, moderately, or poorly differentiated. Poorly differentiated lesions have a higher recurrence (28.6 % versus 13.6 %) and metastatic rate (32.8 % versus 9.2 %) compared to well-differentiated lesions [11].

Clinical workup includes a complete history and physical examination, with emphasis on full skin and regional lymph node examinations. Patients may have concurrent cancer located in various sites, and individuals with SCC may be at increased risk of developing BCC and/or melanoma.

A skin biopsy is performed, making sure to obtain full-thickness sample down to the deep reticular dermis. Punch biopsies are simple to perform in the clinic under local anesthesia and yield good full-thickness samples for pathologic evaluation (Fig. 2.3). Imaging studies are rarely necessary and typically reserved only for locally advanced or clinically detected metastatic lesions.

Fig. 2.3

A standard punch biopsy is depicted. The skin lesion is prepped with alcohol, anesthetized with 1 % lidocaine, and a punch biopsy is performed to obtain a full-thickness specimen for further pathologic analysis. An absorbable suture or steri-strip can be placed for re-approximation of the skin (Illustrator-Karen Howard; Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

The presence of palpable lymph nodes identified by clinical examination or imaging studies should prompt a fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis. Regional nodal involvement significantly increases the risk of recurrence and mortality and is often associated with other histologic findings including lymphovascular invasion, poor differentiation, and perineural invasion (Fig. 2.4a, b). A fine-needle aspiration or core biopsy is generally sufficient for pathologic diagnosis, and excisional biopsies are discouraged as they may confound future definitive surgical interventions. Fortunately, the rate of lymph node metastasis from cutaneous SCC is estimated to only be 0.1 % for early lesions, but increases with more advanced lesions.

Fig. 2.4

Advanced metastatic lymph nodes to the axillary (a) and groin (b) lymph node basins. As depicted, these lesions are locally destructive and are prone to necrosis, infection, and significant disability. Extensive surgical resection is required often with the need for soft tissue coverage for closure and adjuvant radiation therapy to improve regional control (a: Courtesy of Quyen D. Chu, MD, MBA, FACS)

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging classification for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is listed in Table 2.1 [7].

Surgical Considerations

Surgical excision with at least 4–6 mm margins is the standard of care for small, low-risk squamous cell cancers and is the current recommendation in the NCCN guidelines. Zitelli and colleagues reported that for SCC less than 2 cm in diameter, a 4 mm clinical margin of surgical specimen yielded a complete removal with negative margins with a 95 % confidence interval [12]. Postoperative margin assessment should be performed, and re-excision is indicated for positive margins.

Mohs surgery is an excellent surgical technique for high-risk SCC and those in cosmetically sensitive areas. A meta-analysis reported a 5-year disease-free survival rate after Mohs surgery of 97 % for SCC [11]. Another surgical option is excision with compete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment using intraoperative frozen sections or delayed closure/skin grafting with a detailed postoperative margin assessment.

Curettage and electrodesiccation is a process of scraping away tumor tissue then denaturing the area. Up to three cycles can be performed in one session. Overall 5-year cure rate reported for low-risk SCC is 96 % [13]. Three caveats are underscored in the NCCN guidelines: (1) this technique should not be used to treat areas with hair growth due to tumor extending down the follicular structures; (2) if the subcutaneous layer is reached during the course of curettage, surgical excision should be used instead; and (3) biopsy samples should be taken at the time of curettage to analyze for high-risk pathologic features.

The current NCCN recommendations for low-risk SCC are surgical excision with 4–6 mm margins with primary closure, skin graft, or healing by secondary intention, curettage with electrodessication, or radiotherapy for nonsurgical candidates. For high-risk SCC, or those in cosmetically sensitive areas, Mohs surgery or resection with intraoperative frozen sections or radiotherapy is indicated. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) for the evaluation of occult nodal metastatic disease can be performed and may allow for more accurate staging in high-risk feature patients. Criteria to perform an SLNB for SCC are not standardized but often include high-risk features of the primary tumor (size >2 cm, poorly differentiated, evidence of perineural or lymphatic invasion) [14]. Positive sentinel lymph node biopsies should be followed by imaging for complete staging and then completion lymphadenectomy in the absence of distant metastatic disease.

If suspicious lymph nodes are seen clinically or by imaging, FNA or core biopsy is indicated. If the lymph nodes return positive for SCC, regional lymph node dissection is recommended. Those with multiple nodes involved should be considered for adjuvant radiotherapy as multiple studies have shown decreased locoregional recurrence and improved 5-year disease-free survival with this modality [15]. Surgical interventions for widely metastatic SCC are limited to palliative procedures to control bleeding, infection, and/or pain when systemic therapy and/or radiation therapy fails. Although exceedingly uncommon, amputation for uncontrolled tumor is a potential option in advanced SCC arising in the extremities.

Other Treatments

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a nonsurgical treatment option for actinic keratosis and superficial SCC. Although superficial BCC is most responsive to PDT, there has been some success with SCC. In a retrospective study of 35 superficial SCC defined as carcinoma confined to the papillary dermis, complete response rate was reported to be 54 %. However, projected disease-free rate at 36 months after treatment was only 8 % [16]. A few case reports and series report a high recurrence rate, up to 52 %, for SCC in situ and even higher, 82 %, for invasive SCC lesions [17]. Therefore, PDT is not a recommended treatment modality for invasive SCC tumors.

Topical 5-FU applied twice daily or once daily under occlusion for 1.5–2 months has been reported to have a 54–85 % cure rate for intraepithelial SCC. Less intense regimen reduces the clearance rate to only 27–56 % [18]. Imiquimod stimulates the innate immune response by activating cytokines that ultimately induces interferon-gamma release by T cells. Use of imiquimod for SCC is limited. A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial showed 73 % of SCC in situ lesions that achieved clearance after 16 weeks of imiquimod therapy [19]. Current evidence supports the use of topical imiquimod in poor surgical low-risk candidates with SCC in situ lesions.

Diclofenac is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that inhibits cyclooxygenase 2 (COX 2) and thereby reduces the production of prostaglandins. COX 2 enzymes are believed to be upregulated in NMSC lesions. Thus far, topical diclofenac 3 % gel has been approved only for the treatment of actinic keratosis.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is an extracellular signaling receptor in the tyrosine kinase receptor family. Activation of this receptor by various ligands stimulates keratinocyte proliferation. It has been shown that advanced SCC lesions contain EGFR mutation causing overexpression in 43–73 % of cases [20]. Cetuximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against EGFR. It is currently approved for treatment of recurrent or metastatic SCC of the head and neck. A study comparing radiotherapy alone versus cetuximab combined with radiotherapy showed improved locoregional control and overall survival rate in those that received cetuximab [21]. Erlotinib and gefitinib, which disrupt the intracellular signaling cascade after EGFR is activated, are being investigated for use in cutaneous SCC.

External beam radiation therapy can function both as a primary treatment, especially for advanced head and neck SCC in poor surgical candidates or as adjuvant therapy after surgical excision. A meta-analysis reported a 5-year recurrence rate of 10 % after radiotherapy on patients with high-risk primary SCC [11].

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy that arises in the dermoepidermal junction. It commonly affects elderly Caucasians and was originally described by Toker in 1972 as trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Other names include Toker tumor, primary small cell carcinoma of the skin, primary cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor, and malignant trichodiscoma. Although rare, MCC incidence rates are increasing rapidly. The tumor often appears as an asymptomatic erythematous nodule and may resemble a basal cell carcinoma, a common misdiagnosis both clinically and histologically (Fig. 2.5). The pathogenesis of MCC is controversial. One thought is it arises from Merkel cells, which are part of the amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation system located in the basal layer of the epidermis and hair follicles. Another hypothesis is that MCCs originate from immature stem cells that acquire neuroendocrine features during malignant transformation.

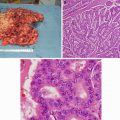

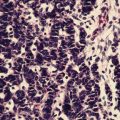

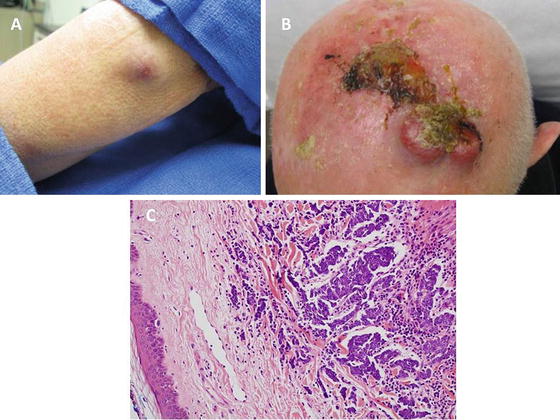

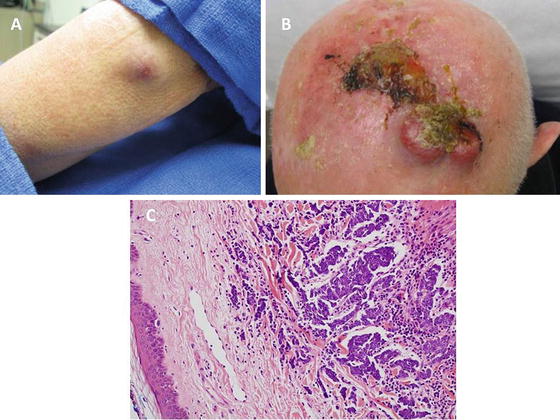

Fig. 2.5

A typical Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is shown on the extremity as an erythematous nodule that exhibited a rapid growth phase (a). MCC can be locally aggressive and has a high potential for recurrence and metastasis (b). Adjuvant radiation therapy following the wide excision of MCC has proven benefit in reducing the local recurrence rate for advanced lesions. (c) Photomicrograph depicting clusters of neoplastic cells within the dermis having the finely granular chromatin pattern characteristic of Merkel cell carcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin X 200) (c: Courtesy of Barry DeYoung, MD, Wake Forest School of Medicine)

MCCs can be characterized by AEIOU features: Asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, Expanding rapidly, Immune suppression, Older than 50 years, and Ultraviolet-exposed site on a person with fair skin [22]. In a SEER data review of 1,034 patients, MCC was more common in males and patients geographically located in sun-exposed climates; 94 % were Caucasian, 76 % were older than 65 years (median 75), and 48 % occurred on the head [23]. MCC has been shown to be more common in immunosuppressed populations such as solid organ transplant recipients and HIV patients. Accordingly, MCC can be aggressive and should be considered to have a high lethal potential with an estimated 1 in 3 patients succumbing to the disease. Of the patients for which MCC is the cause of mortality, half of the patients will die within 4 years of the initial diagnosis.

In 2008, Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) was discovered and found to be integrated into the host genome of over 80 % of patients with MCC, and this association has been validated by multiple other studies [24]. An increased incidence of MCCs was found in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who are relatively immunosuppressed and have a high rate of MCV detected in their MCC tumors [22].

When MCC is suspected, a punch biopsy or full-thickness biopsy should be performed. There are three main histologic patterns: (1) solid type- most common type, composed of irregular groups of tumor cells interconnected by strands of connective tissue; (2) trabecular type- well-defined cords of cells that form invading columns or cords; and (3) diffuse type- exhibits poor cohesion and a lymphoma-like diffuse type of growth. The pathologic diagnosis is difficult due to its similarity to small round blue cell tumors (small cell carcinoma of the lung, cutaneous large cell lymphoma, neuroblastoma, metastatic carcinoid, amelanotic melanoma, sweat gland carcinoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and Ewing sarcoma). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining should be confirmed by immunohistochemistry (IHC). CK-20 is both sensitive and specific for MCC with a positivity in 89–100 % cases, and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) is consistently negative in MCC [25].

Histologic features that may have prognostic significance include: tumor thickness, presence of lymphovascular invasion, and tumor growth pattern. The AJCC lists site-specific prognostic factors: measured thickness (depth), tumor base transection status, profound immune suppression, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the primary tumor, growth pattern of primary tumor, size of tumor nests in regional lymph nodes, clinical status of regional lymph nodes, regional lymph nodes pathologic extracapsular extension, isolated tumor cells in regional lymph node(s) [7]. The majority of patients die from distant metastases involving liver, bone, lung, brain, or distant lymph nodes. Tumors greater than 2 cm in diameter at the time of diagnosis have been shown to have a negative influence on survival.

Surgical Considerations

MCC has a propensity for local recurrence and regional lymph node metastases. Diagnosis is typically made with a skin biopsy after a complete skin and lymph node examination. In 2010, the AJCC published the new staging system for MCC, which is based on primary tumor size and nodal status. The primary lesion should be examined for satellite lesions or dermal seeding and the extent of disease assessed. If lymph nodes are clinically involved, fine-needle aspiration or core biopsy should be performed with consideration of open biopsy if negative. Diagnostic imaging such as CT, MRI, and/or PET/CT should be performed to evaluate disease extent and rule out distant visceral metastases particularly when signs or symptoms of metastatic disease warrant further investigation.

Surgical management continues to be the primary treatment for clinically localized MCCs. Wide local excision with 1–2 cm margins to investing fascia and SLNB are the current recommendations for early stage cancers. In one study, an average margin width of 1.1 cm had a low (8 %) recurrence rate if negative, and a decreased local recurrence rate was not associated with a margin of more than 1 cm [26]. In areas of difficult margins, Mohs micrographic surgery may be an additional option. Primary radiation therapy has also been used successfully in selected patients.

SLNB, although not clearly proven to impact survival, is recommended. The techniques performed are similar to melanoma. Sentinel lymph nodes should be assessed using IHC for more effective metastatic identification, including CK-20 staining. A low rate of lymph node metastases from primary tumors <1 cm has been observed, but the low risk has not been clearly reproducible, and omitting the SLNB procedure for smaller tumors does not appear to be widely accepted. If lymph nodes are clinically positive, FNA or core biopsy should be performed for confirmation followed by either complete lymphadenectomy and/or radiation therapy (RT) for regional control.

Other Treatments

MCC is radiosensitive, and therefore RT is often used adjunctly for locoregional disease control. In an extensive review of the literature, a decreased local recurrence of 10.5 % with RT versus 52.6 % without was found [27]. SEER data review of patients stage I–III had an increased overall survival when treated with surgery plus radiation compared with patients treated with surgery alone. Adjuvant radiation was a component of therapy in 40 % of the surgical cases, and the median survival for those patients receiving adjuvant RT was 63 months compared with 45 months for those treated without. The use of RT was associated with an improved survival for patients with all sizes of tumors, but the improvement was particularly prominent for primary lesions larger than 2 cm [28]. However, not all studies have found an increased survival benefit. NCCN guidelines recommend a total radiation dose of 50–56 Gy in patients with clinically negative margins who are considered to be at significant risk for residual subclinical disease at the resection site.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree