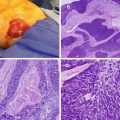

Fig. 3.1

Pathophysiology of DCIS and LCIS

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ

DCIS represents approximately 20 % of all newly diagnosed breast cancers. Risk factors for DCIS are similar to invasive breast cancer and include family history of breast cancer, increased breast density, obesity, and nulliparity or late age at first live birth. Like invasive breast cancer, DCIS is also a component of the inherited breast-ovarian cancer syndrome defined by mutations in the BRCA genes; mutation rates are low and similar to those for invasive breast cancer (about 5 % of all cases). Similar to invasive breast cancer, DCIS tends to occur at a younger age in women with inherited BRCA mutations [3, 4]. The average age of diagnosis is between 54 and 56, with the majority of cases found in postmenopausal women. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for women diagnosed from 1984 to 1989, the risk of death from breast cancer in women with DCIS is low, estimated at 1.9 % within 10 years, and is most commonly related to an invasive recurrence in the breast [5].

Pathophysiology

DCIS is the proliferation of abnormal ductal epithelial cells that are limited to and have not invaded beyond the basement membrane. DCIS is considered a precursor of invasive carcinoma, but does not fully express the malignant phenotype. The progression to invasive breast cancer is not obligatory and cannot be reliably predicted. It is also critically important to keep in mind that the distinction between low-grade DCIS and atypical duct hyperplasia (ADH) can be difficult, even for experienced pathologists, and some have advocated a more conservative approach to these “borderline” lesions [6, 7].

Classification of DCIS into histopathological subtypes facilitates prognostication and management decisions [8]. Conventional histologic patterns include comedo, solid, cribriform, papillary, and micro-papillary. Grading of low, intermediate, and high is also assigned based on nuclear features including nuclear size, shape, chromatin texture, and mitotic activity. While papillary and cribriform patterns often have low nuclear grade, comedo tumors generally have high nuclear grade. Comedo lesions have a solid growth pattern and central necrosis with calcifications and are associated with an increased risk of local recurrence and invasion [9].

Pathologists should examine tissue specimens excised for DCIS thoroughly to exclude small foci of invasive disease. The size and overall extent of the DCIS should be reported along with the margin width – distance to the resection margin. Nuclear grade, distance to the closest margin, and extent of margin involvement should also be examined and reported. Testing the specimen for estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) is done routinely to guide management decisions. However, it is generally better to wait until the definitive resection to test for ER and PR rather than testing needle biopsy material, since any invasive component, if present, should be assessed preferentially.

Diagnosis

Ninety percent of DCIS lesions are identified radiographically by the presence of microcalcifications. Less common presentations include a palpable mass, mammographic mass, Paget’s disease of the nipple, or bloody nipple discharge. Mammographic patterns that represent DCIS include punctate, linear, or branching calcifications reflecting a ductal orientation [9, 10]. All patients with newly diagnosed DCIS should have diagnostic mammographic views with magnification to fully assess morphology and extent of calcifications. Diagnosis should usually be confirmed by stereotactic core biopsy, which allows for surgical planning. When stereotactic biopsy is not possible because of depth, breast tissue that is too thin or implants, wire-localized excisional biopsy can be substituted. However, this practice should be the exception, with needle biopsy being preferred.

Silverstein and colleagues devised a prognostic index that correlated the risk of local recurrence with several pathologic features [11]. Features originally included size, margin, and grade but now also include patient age (Table 3.1). Although this index was reported to be able to identify patients with such a low risk of recurrence that they might not need radiation, other studies indicate that most DCIS patients benefit from irradiation after breast-conserving surgery (see below).

Table 3.1

Van Nuys prognostic index

Score | Size | Margin | Pathological classification | Age (yrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | <15 mm | >10 mm | Non-high-grade lesion w/o comedo necrosis (nuclear grade 1 or 2) | >60 |

2 | 16–40 mm | 1–9 mm | Non-high-grade lesion w/ comedo necrosis (nuclear grade 1 or 2) | 40–60 |

3 | >41 mm | <1 mm | All high-grade lesion w/ or w/o necrosis (nuclear grade 3) | <40 |

Treatment

Therapeutic strategies to manage DCIS include surgery, radiation therapy, and adjuvant endocrine therapy, with the goal of preventing the development of recurrence, especially with invasive cancer. In the past, DCIS was treated with total or even modified radical mastectomy, but subsequent trials have suggested that breast-conserving surgery is safe for DCIS and that removal of lymph nodes is not beneficial. Mastectomy affords a cure rate of approximately 98 %, with local recurrence rates at approximately 1 % [12]. Mastectomy is still appropriate for some patients with large tumors (>4 cm, depending on breast size), multicentric lesions (meaning DCIS in more than one quadrant of the breast; however, this is now being challenged), inability to obtain negative margins despite multiple attempts, recurrence after breast conservation (particularly with prior radiation therapy; however, recent trials are examining the role of repeat BCT in this setting), lack of access to a radiation facility, risk of noncompliance, or patient preference. Approximately 96 % of recurrences occur in the same quadrant, implicating the presence of residual disease as the underlying cause. Women treated with mastectomy for DCIS are good candidates for immediate breast reconstruction with implants or autologous flaps, since lymph node involvement and need for radiation are unlikely.

Although mastectomy is effective, it is more aggressive than most women with DCIS require. Breast-conserving therapy (BCT) – wide excision with negative margins followed by radiation – is associated with less morbidity compared to mastectomy but has a higher risk of local recurrence. National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol B-17 (NSABP B-17) randomized 818 women with DCIS to excision alone versus excision followed by radiation. There was a reduction in the incidence of invasive ipsilateral recurrences from 21.1 % to 8.1 % when radiation was added, but no difference in the overall survival (86 % vs. 87 %) at 12 years. There was also a reduction in noninvasive recurrence from 18.3 to 8.9 %. At 8 years follow-up, the risk of contralateral invasive breast cancer (3.5 %) was similar to the rate in the ipsilateral (3.9 %) breasts treated with lumpectomy and irradiation [12]. At 15 years, ipsilateral invasive recurrence was also reduced with the addition of radiation compared to excision alone (8.9 % vs. 19.4 %) [13]. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) examined similar randomized groups (excision alone vs. excision followed by radiotherapy) in 1,111 women with DCIS detected mammographically which were <5 cm. Adequate lumpectomy, as in B-17, was defined by negative margins, meaning “no tumor on ink.” Recurrence rates at 10 years for excision alone were significantly higher than for those treated with excision followed by radiation (26 % vs. 10 %). Like NASBP B-17, disease-free and overall survival was similar in the two groups [14]. These data supported the recommendation for all patients receiving breast-conserving surgery for DCIS to receive postoperative radiation. Re-excision(s) or mastectomy may be required to obtain negative margins. A negative margin – an absence of tumor at the inked surface of the specimen – is considered a minimum requirement. A margin width of 1–2 mm is usually sufficient for women who undergo radiation therapy. A wider margin, ideally 10 mm if achievable, is preferred for women considering breast-conserving surgery alone. Obtaining wider margins of excision and whether this can obviate the need for radiation is a current area of controversy [13, 15–17]. The original analysis which derived the Van Nuys Prognostic Index suggested that women with a lower score may have a low risk for recurrence and therefore not require radiation. Subsequent attempts to validate and replicate this analysis have not been consistent [18, 19]. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 5194 (ECOG) also examined excision without radiation in women with DCIS. Limitations for the extent of DCIS were established for low/intermediate and high-grade lesions, and all excised specimens had a minimum surgical margin of 3 mm. Tamoxifen was allowed but not required following surgery. After a median follow-up of 6.7 years, the 5-year rate of local recurrence was 6.1 % for low/intermediate grade lesions and 15.3 % for high-grade lesions. While longer follow-up is necessary, the study suggests that carefully selected patients treated with breast-conserving surgery without radiation had low rates of local recurrence [20]. To date there is no clinical or pathologic feature that reliably predicts that excision without radiation will have no local failure, and ideal nomograms to assist in this evaluation are still to be determined [21]. Preliminary data from ECOG 5194 suggest that a gene expression profile analysis may provide further assistance in the identification of a subset of patients who may have a low enough risk of recurrence after excision that they may not have a benefit from adjuvant radiation [22]. Although this DCIS score can predict risk of recurrence without radiation, it does not truly predict the benefit or lack of benefit from the addition of radiation.

The incidence of lymph node involvement in women with DCIS is 1–2 % and likely related to a missed focus of invasion in excised specimens. Retrospective analysis of NSABP B-17 and B-24 suggests that sentinel lymph node biopsy would generally have a low yield and is unnecessary. Even when apparent cancer cells are found in axillary lymph nodes of patients who are not found to have any evidence of invasion in the breast primary, the overall outcomes of these patients do not appear to be different from other DCIS patients. There may be as much as a 20 % chance of finding an invasive cancer within an excision specimen after an initial needle biopsy diagnosis of DCIS (i.e., upstaging). The decision to perform a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) may be patient-driven in order to avoid a second operation. Relative indications to perform SLNB in patients with DCIS include those undergoing mastectomy (because of difficulty with subsequent SLNB) and risk factors for invasion such as palpability, comedo morphology, necrosis, or recurrent disease.

Adjuvant Systemic Therapy

It was the observation in patients with invasive disease that tamoxifen – a mixed estrogen agonist/antagonist – decreased contralateral breast cancer and ipsilateral recurrence that made it attractive for use in DCIS. Between 1991 and 1994 the NSABP trial B-24 randomized 1,804 women with DCIS treated with excision and radiation to either tamoxifen or placebo for 5 years. The ipsilateral breast recurrence rates for women less than age 50 were 33.3/1000 versus 20.8/1000 with placebo and tamoxifen, respectively, and for women 50 and older were 13/1000 with placebo versus 10.2/1000 with tamoxifen. At 5 years, the incidence of either subsequent invasive or noninvasive breast cancer in either breast was reduced by 37 %; the incidence of invasive breast cancer in either breast was reduced from 7.2 % to 4.1 % with tamoxifen. Nevertheless, tamoxifen had no effect on overall survival. Among women with ER-positive disease, there was a significant reduction in any breast cancer event, while in women with ER-negative disease, there appeared to be only a trend toward reduction [23, 24]. The use of aromatase inhibitors for DCIS is currently under study. For example, the NSABP B-35 trial compares tamoxifen with anastrozole for women with DCIS treated with lumpectomy + irradiation.

Lobular Carcinoma In Situ

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) is a predictor for increased risk of development of invasive breast cancer but is neither a premalignant lesion nor an anatomic marker for the site of invasive disease. The risk is conferred to both the ipsilateral and contralateral breasts. It is usually found incidentally on biopsy that is performed for another lesion. The mean age of diagnosis in many series is between 44 and 46, and more than 80 % of cases are found in premenopausal women. Because of the absence of mammographic or clinical presentation, the true incidence of LCIS is unknown. The SEER database reports the incidence as 3.19 per 100,000 women [25].

Pathophysiology

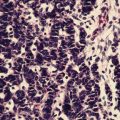

LCIS is a noninvasive abnormal proliferation of cells in the terminal duct and lobule of the breast (see Fig. 3.1). The growth of cells within the acini of the lobule often has pagetoid extension into the ducts. E-cadherin staining is used to differentiate cells of ductal and lobular origin. The immunohistochemical stain is strongly present in the membrane of DCIS specimens but is absent in LCIS [26]. Two subtypes of LCIS have been described: classic and pleomorphic (discussed below). Classic LCIS has smaller nucleoli and less frequent mitotic figures compared to pleomorphic.

The presence of LCIS is considered a risk factor for subsequent invasive cancer. Although the risk of developing invasive lobular carcinoma is higher than for the general population, the majority of women with LCIS who develop cancer develop ductal carcinoma. The time to the development of invasive cancer is generally in the range of 10–15 years [9]. In one series, after a 10-year follow-up of 4853 cases of LCIS, 7.1 % developed invasive cancer with an equal frequency of cancer occurring in both breasts [27]. The lifelong risk of developing an invasive cancer is estimated to be 1 % per year and the relative risk two-fold compared to women without LCIS. [28].

Treatment

The management of LCIS discovered on core needle biopsy is controversial. Several series between 1999 and 2008 report an underestimation of malignancy after comparing core needle biopsies with excised specimens ranging from 0 to 50 %, with an overall underestimation of malignancy of 27 %[29]. Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines suggest excision for all patients diagnosed with LCIS on core needle biopsy [30].

When LCIS is diagnosed or found in isolation on excisional biopsy, no further surgical intervention is required. Unlike DCIS, clear margins are not required and ipsilateral mastectomy and radiation are not indicated. There is no role for axillary lymph node biopsy or dissection in the absence of invasive disease. Local recurrences following excision, as seen with DCIS, are uncommon. If invasive carcinoma is detected in the excision specimen, then appropriate staging and treatment strategies should be initiated.

Women with LCIS should be counseled on the increased but still relatively low risk of ipsilateral or contralateral breast cancer, and the alternatives of observation, chemoprevention, and prophylactic mastectomy should be discussed. In the absence of other risk factors (family history, BRCA mutation, personal history of breast cancer), prophylactic mastectomy should be considered a drastic measure and only used if patients insist. To date there are no randomized efficacy trials comparing observation to prophylactic mastectomy. If the observation alternative is elected, careful surveillance should be continued indefinitely. Current guidelines recommend a history and physical exam every 6–12 months and annual screening mammography. LCIS places a patient at intermediate risk, and according to current guidelines, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not indicated for surveillance in the absence of a strong family history [30].

Chemoprevention

In the NSABP P-1 trial 13,338 high-risk women (6 % had LCIS) were randomized to receive tamoxifen or placebo for 5 years. The risk of invasive breast cancer was reduced from 42.5/1,000 to 24.8/1,000 with tamoxifen at 7 years. For noninvasive breast cancer, the risk reduction was from 15.8/1,000 to 10.2/1,000. The rate of development of breast cancer in the tamoxifen group was 6 versus 12 in the placebo group per 1,000 women [31]. Although there were not a large number of LCIS patients in the P-1 trial, the proportional reduction in breast cancers with tamoxifen for this subset was even greater than for the trial as a whole.

Raloxifene, another selective estrogen receptor modulator, has also been evaluated in postmenopausal high-risk women, including those with LCIS. In the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial, over 19,000 patients (9 % had LCIS) were randomized to compare tamoxifen with raloxifene. The trial demonstrated that both agents were equally effective in reducing the incidence of invasive breast cancer. Among women with a history of LCIS, both drugs were equally effective at reducing the incidence of invasive breast cancer. Tamoxifen had reduced the incidence of DCIS and LCIS by half. Raloxifene was not quite as effective as tamoxifen against noninvasive cancer but had fewer serious side effects [32].

Pleomorphic LCIS

PLCIS is distinguished as an aggressive subtype of LCIS with larger nuclei and increased pleomorphism and is often associated with microcalcifications and central necrosis. Many of these features overlap with DCIS, making distinction difficult. Surgical excision with negative margins is recommended, but no evidence supports wide margins or radiation for this lesion [29]. Some authors recommend treating PLCIS like DCIS.

Phyllodes Tumors

Phyllodes tumors are rare breast lesions made up of stromal and epithelial components. The tumor was first described in 1838 by Johannes Muller who originally named it cystosarcoma phyllodes. For the sake of uniformity of histologic and biologic variants, the World Health Organization recommended in 1982 that the range of lesions fall under the heading of phyllodes tumors. These lesions account for <0.5 % of all breast tumors with a median age of 40–45 [33, 34]. The majority of patients present because of a palpable breast lump that is firm, mobile, and smooth. The tumor varies in size, but in one large series of 106 patients, over 70 % were less than 5 cm at the time of diagnosis [35].

Pathophysiology

Phyllodes tumors are histologically graded into benign, borderline, or malignant tumors based on characteristic features. Some authors have noted that there is not a clear correlation between histology and clinical outcome [33, 36]. All three classifications of phyllodes recur locally, but only borderline and malignant tumors metastasize [33]. Approximately 25 % of phyllodes tumors are malignant but only about 17–22 % metastasize. The most common reported sites of metastases are in the lung, soft tissue, bone, and pleura. Histologic examination of metastases shows greater resemblance to sarcomas [33, 34].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree