Fig. 14.1

Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lower lip mucosa with characteristic ulceration

Three histologic patterns can be identified, the cribriform (“Swiss cheese”), tubular, and solid, and they may coexist in the same tumor. Unlike other high-grade malignancies, ACC has good 5-year overall survival (70–90 %) that drops dramatically at 10 years (30–70 %) and even more at 15 years (less than 50 %). Due to the tumor’s neurotropism and high possibility of skip metastasis along cranial nerves, radical surgery and wide-field radiotherapy are recommended. Often the mandible may be invaded by ACC of the lower lip, and thus a composite resection is performed. The presence of metastasis (usually to the lungs and less commonly to the cervical lymph nodes and bone) has less impact on survival than the size of the tumor (Fig. 14.2a, b). Some poor prognostic factors for ACC are tumor size greater than 4 cm, tumor present at the resection margins, and the presence of 30 % or more of the solid variant [34–48].

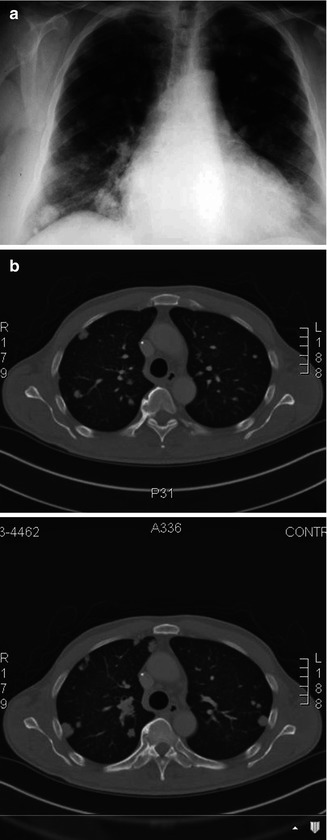

Fig. 14.2

(a) Plain chest radiograph demonstrating lung metastasis from adenoid cystic carcinoma. (b) Computer tomography demonstrating lung metastasis from adenoid cystic carcinoma

In 1983 the polymorphous low–grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) was reported under the terms lobular carcinoma and terminal duct carcinoma of the salivary glands. The specific histopathologic features, clinical presentation, and behavior segregated PLGA from other tumors. Overall PLGA is a low-grade malignancy with indolent course and low metastatic potential found almost exclusively in the minor glands, most often those in the palate. In the case series reported by Pires et al., there were 28 PLGAs (11.8 %) involving the intraoral minor salivary glands, and of those six were located in the upper lip, none were found in the lower lip [4]. Similar percentages of PLGAs among minor salivary gland malignant neoplasms can be found in the series by Jansisyanont et al., Van heerden et al., and Isaccson and Shear, where tumors represented 11.3, 15.7, and 10.5 % of all malignant cases [9, 17, 49]. Unfortunately, the specific tumor locations are not reported in the later studies.

A relatively small non-ulcerated, non-painful, firm, elevated submucosal slow-growing swelling is the common presentation. The tumor occurs in older male or female patients in their fifth to eighth decade of life. Cervical nodal involvement is reported in 10 % of the patients at the time of initial presentation. Histopathologically the tumors lack capsule and demonstrate infiltration into surrounding tissues. Difficulties in differentiating PLGA from ACC may be encountered on routine hematoxylin-eosin stains, especially due to the presence of perineural invasion in both of tumors. The perineural invasion in PLGA is no significance though and wide local excision is adequate treatment with no need for radiotherapy [45–47, 50–57].

Acinic cell adenocarcinomas most commonly (>80 %) involve the parotid, accounting for 18 % of malignant salivary tumors and 6.5 % of all salivary neoplasms. In general these are indolent neoplasms with low metastatic potential and recurrence rates, especially when they involve the minor glands. The largest series specifically on acinic cell carcinoma of the minor salivary gland is reported by Omlie et al. in 2012. The series included 21 cases; out of those 5 involved the upper lip and none in the lower lip. In another series by Triantaphilidou et al., out of 11 cases only one was found in the lip, and finally, out of 14 tumors only two were located in the upper lip in the report by Pires et al. [4, 58, 59]. Wide local excision is usually adequate, while radiation therapy is reserved for recurrences or when complete excision cannot be accomplished. Although overall rare, recurrences have been reported and successfully salvaged with additional surgery, and thus careful long-term follow-up should be employed for these patients.

14.3 Melanoma of the Lip

The first case of oral cavity mucosal melanoma was described in 1859 by Weber. The tumor was found in the palate, which remains the most common location for this malignancy to date followed by the guns [60–64]. Since the original description primary oral mucosal melanoma (OMM) represents a small percentage of tumors unlike their cutaneous counterparts and is a highly aggressive tumor. OMM represent approximately 0.2–8 % of all melanomas in the USA and Europe, but it appears this incidence differs with geographic location. In regard to oral cavity tumors, OMM represent approximately 0.26 % demonstrating the rarity of this entity [65, 66]. There is a higher male-to-female predilection (2.1–1) for OMM, and the median age of presentation is reported 20 years later than cutaneous melanoma with a mean age in the mid-50s [66–69]. The etiology of OMM remains unknown. In the 2010 American Joint Commission of Cancer staging system, mucosal melanoma of the head and neck was added as an entity with staging starting at T3 (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1

2010 AJCC staging for mucosal melanoma of the head and neck

Definition (clinical and/or pathologic presentation) | (T) Tumor stage assigned |

Mucosal disease | T3 |

Mucosal disease, but tumor involves deep soft tissue cartilage, bone, overlying skin (moderately advanced disease) | T4a |

Mucosal disease, but tumor involves brain, dura, cranial nerves (IX, X, XI, XII), masticatory space, carotid artery, prevertebral space, mediastinal structures | T4b |

(N) Nodal stage assigned | |

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | Nx |

No regional lymph node metastasis present | N0 |

Presence of regional lymph node metastasis | N1 |

(M) Metastasis stage assigned | |

No distant metastasis | M0 |

Distant metastasis present | M1 |

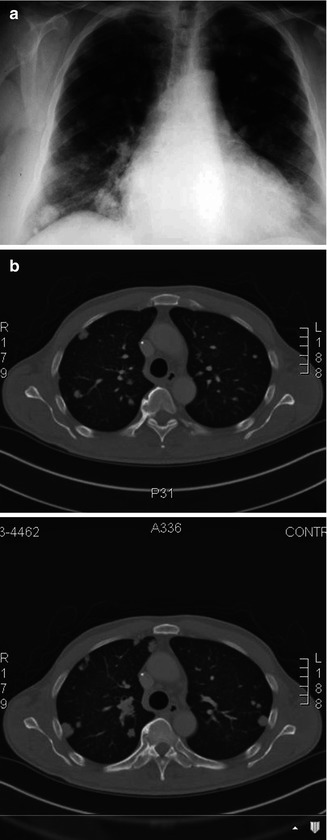

Mucosal melanoma of the lip specifically is even rarer entity with only few cases or series found in the literature [65, 70, 71]. In all series and case reports, the theme appears similar, late diagnosis advanced disease at time of presentation and poor prognosis [70–72]. Nodal involvement appears to consistently influence survival as does misdiagnosis that leads to inadequate treatment and multiple recurrences [73]. Radiographic surveillance of the head and neck with CT or MRI should be included in the work-up with particular attention to invasion or the underlying bone of the maxilla or the mandible (Fig. 14.3). Surveillance for distant metastasis should also be included in the initial work-up especially in advanced cases. Surgery is the treatment of choice for these malignancies. Aggressive wide local excision is the treatment of choice for lip tumors similar to the recommendations for the oral cavity OMM. The need for neck dissection should be considered based on the clinical and radiographic findings. Recurrences could be treated with additional surgery. Strong consideration should be given to chemotherapy with high doses of IL-2 or newer options such as vemurafenib and ipilimumab in the presence of distant metastasis for eligible patients as they appear to be the only potential chance for cure [74–77]. Retrospective studies on patients with mucosal melanomas have shown an improvement in local control with adjunct radiotherapy compared to surgery alone, but the impact to long-term survival remains unknown [78]. Unfortunately patients with mucosal melanoma develop distant metastasis and have poor prognosis despite adequate surgical resection especially when advanced stage disease is present (Fig. 14.4a, b).

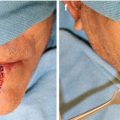

Fig. 14.3

Mucosal melanoma of the upper lip with involvement of the anterior maxilla

Fig. 14.4

(a) Computer tomography demonstrating lung metastasis from upper lip melanoma. (b) Positron emission tomography scan (PET) of the same patient demonstrating the hypermetabolic activity of the lung metastasis

14.4 Mesenchymal Malignancies

Mesenchymal origin malignant tumors are overall rare entities in the head and neck with aggressive behavior and generally poor prognosis. Only few cases from various entities are reported in the lips. The types of mesenchymal tumors reported throughout the literature include descriptions of round cell, spindle cell, and mixed cell sarcomas in addition to more specific lymphangiosarcomas or neurogenic sarcomas [79–83]. Only few cases from various entities are reported specifically in the lips. For example, out of 136 dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, a slow-growing but locally aggressive skin malignancy – that can be found in the head and neck in 12–15 % of the time – only one case was found in the lips [84]. In the oldest case series of sarcomas found in the lips reported in 1934 by Cholnocky, 20 tumors were located specifically in the lips, and the author added another four cases all located in the vermillion border. It is thus difficult based on the available literature to draw conclusions on incidence gender predilection and provide treatment recommendations for such entities. Generally speaking surgical resection with wide tumor-free margins is the generally accepted approach. Each case though requires careful review of pathology to determine the exact entity on hand and tailor treatment appropriately.

14.5 Conclusion

Although epithelial origin cancers present with the highest frequency in the lips, other types of malignancies can be commonly encountered as well. Careful review of the histopathologic findings is crucial to differentiate some of the less common pathologic entities. Appropriate oncologic work-up should include at least advanced imaging of the head and neck and it is crucial for treatment planning. Discussion in multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board to obtain input from other oncologic specialties is indicated as well especially in rare cases where specific treatment guidelines may not be readily available.

References

1.

2.

MacIntosh R (1995) Minor salivary gland tumors: types, incidence and management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am 7:573–589

3.

Carlson EO, Ord RA (2008) Tumors of the minor salivary glands. In: Carlson EO, Ord RA (eds) Textbook and color atlas of salivary gland pathology, vol 1, 1st edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Ames

4.

5.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

Potdar GG, Paymaster JC (1969) Tumors of minor salivary glands. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 28(3):310–319PubMedCrossRef

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree