The guiding principles of nipple-sparing mastectomy (complete removal of the breast from its skin and reconstructing without changing the appearance of the breast) are based on patient safety followed by oncologic safety. Recent advances have also taken into account cosmetic outcome. The ultimate in cosmetic outcome after mastectomy with reconstruction includes preservation of the nipple-areola complex, called a nipple-sparing mastectomy. The evidence-based transition and transformation to nipple-sparing mastectomy from both an oncologic standpoint and a cosmetic perspective are outlined in this article.

Key points

- •

All new surgical techniques need to first be evaluated for safety and efficacy.

- •

Nipple-sparing mastectomy is technically feasible but challenging.

- •

On short-term follow-up, nipple-sparing mastectomy is oncologically safe.

- •

Impact on sensation, body image, and quality of life are yet to be fully determined.

Historical perspective

The surgical management of breast cancer has changed dramatically over the years.

- •

1600 bc : oldest recorded history (a scroll) comes from ancient Egypt and stated that there was no treatment of breast cancer.

- •

∼400 bc : Hippocrates also recommended no surgical management for breast cancer, because it would certainly only hasten the patient’s death.

- •

First century ad : Greek physician, Leonides, performed the first operative management of breast cancer, called the escharotomy method.

- ○

A hot poker made repeated incisions, burning the entire breast off the chest wall. Most women died of surgical infection.

- ○

- •

100 years later: Galen is credited with the first surgical cure for breast cancer.

- •

Renaissance era: new surgical instruments were being created. Without anesthesia or antisepsis, the goal was to remove the breast swiftly.

- ○

The Guillotine method: amputation of the breast with a large sharp knife without reapproximating the skin. Most women died of exsanguination or subsequent infection.

- ○

- •

Eighteenth century: birth of the nipple-sparing mastectomy.

- ○

A surgeon, Jean Louis Petit, advocated leaving all the skin not involved with tumor including the nipple-areola disk during the procedure and, in essence, described the concept of the nipple-sparing mastectomy.

- ○

His beliefs and methods were not adopted.

- ○

- •

Late nineteenth century to mid-twentieth century: the Halsted era

- ○

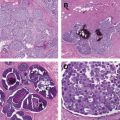

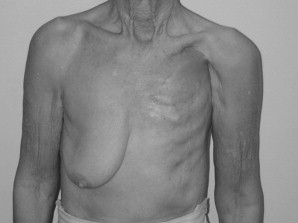

Halsted described the exact technique to perform a radical mastectomy. Operative mortality decreased but the operation was disfiguring ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1

The Halsted radical mastectomy.

- ○

He had 2 advantages: the advent of anesthesia and antisepsis.

- ○

The initial operation: complete removal of the breast with all the overlying skin (a skin graft for coverage of the chest wall) and removal of level I to III axillary lymph nodes and the pectoralis major and minor muscles.

- ○

Later operation: the additional removal of the latissimus dorsi, supscapularis, teres minor, and serratus muscles.

- ○

The Halsted radical mastectomy became the primary treatment of breast cancer for the next 70 years. During that era, a surgeon-pathologist (Hagensen) at Columbia University noted that the more radical the operation became, the survival rates from breast cancer did not likewise increase.

- ○

This observation was also noted by European colleagues (Veronesi); this opened the door to consideration of a less radical operation.

- ○

In 1948, Patey and Dyson introduced the concept of the modified radical mastectomy; a modified radical mastectomy includes removal of the entire breast, level I to III lymph nodes, and the necessary skin (including nipple-areola disk) to allow primary closure flat against the chest wall, with minimal redundancy of skin. No muscles would be removed.

- ○

Historical perspective

The surgical management of breast cancer has changed dramatically over the years.

- •

1600 bc : oldest recorded history (a scroll) comes from ancient Egypt and stated that there was no treatment of breast cancer.

- •

∼400 bc : Hippocrates also recommended no surgical management for breast cancer, because it would certainly only hasten the patient’s death.

- •

First century ad : Greek physician, Leonides, performed the first operative management of breast cancer, called the escharotomy method.

- ○

A hot poker made repeated incisions, burning the entire breast off the chest wall. Most women died of surgical infection.

- ○

- •

100 years later: Galen is credited with the first surgical cure for breast cancer.

- •

Renaissance era: new surgical instruments were being created. Without anesthesia or antisepsis, the goal was to remove the breast swiftly.

- ○

The Guillotine method: amputation of the breast with a large sharp knife without reapproximating the skin. Most women died of exsanguination or subsequent infection.

- ○

- •

Eighteenth century: birth of the nipple-sparing mastectomy.

- ○

A surgeon, Jean Louis Petit, advocated leaving all the skin not involved with tumor including the nipple-areola disk during the procedure and, in essence, described the concept of the nipple-sparing mastectomy.

- ○

His beliefs and methods were not adopted.

- ○

- •

Late nineteenth century to mid-twentieth century: the Halsted era

- ○

Halsted described the exact technique to perform a radical mastectomy. Operative mortality decreased but the operation was disfiguring ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1

The Halsted radical mastectomy.

- ○

He had 2 advantages: the advent of anesthesia and antisepsis.

- ○

The initial operation: complete removal of the breast with all the overlying skin (a skin graft for coverage of the chest wall) and removal of level I to III axillary lymph nodes and the pectoralis major and minor muscles.

- ○

Later operation: the additional removal of the latissimus dorsi, supscapularis, teres minor, and serratus muscles.

- ○

The Halsted radical mastectomy became the primary treatment of breast cancer for the next 70 years. During that era, a surgeon-pathologist (Hagensen) at Columbia University noted that the more radical the operation became, the survival rates from breast cancer did not likewise increase.

- ○

This observation was also noted by European colleagues (Veronesi); this opened the door to consideration of a less radical operation.

- ○

In 1948, Patey and Dyson introduced the concept of the modified radical mastectomy; a modified radical mastectomy includes removal of the entire breast, level I to III lymph nodes, and the necessary skin (including nipple-areola disk) to allow primary closure flat against the chest wall, with minimal redundancy of skin. No muscles would be removed.

- ○

Birth of breast reconstruction and subcutaneous mastectomy

In the 1950s, silicone gel implants came on the scene. Women with breast cancer were not offered immediate reconstruction for 2 reasons:

- •

Development of a recurrence or distant disease, mostly likely within 3 years of a woman’s cancer diagnosis. The woman would be declared a survivor before any breast reconstruction was performed.

- •

The techniques of immediate reconstruction after mastectomy were still in their infancy. If the woman lived with all the imperfections of a mastectomy without reconstruction for a significant period, she would be more appreciative of any reconstructive outcome.

Early experience with immediate breast reconstruction came from women having subcutaneous mastectomies for benign disease. A subcutaneous mastectomy was performed using, most commonly, an inframammary incision, with removal of most of the breast tissue, leaving a rim of normal breast tissue on the undersurface of the native breast skin, especially subareolar. No skin was removed, including the nipple areolar disk, akin to a nipple-sparing mastectomy. Thick mastectomy flaps (>10 mm) were raised, leaving a cushion of tissue anterior to the implant and beneath the skin. This cushion maintained skin viability and created a more natural feel to the reconstruction. Because this operation was for benign disease, the oncologic safety was not questioned.

By the 1970s, the modified radical mastectomy was gaining traction and women demanded immediate reconstruction. Plastic surgeons had some native breast skin, albeit thinner than a subcutaneous mastectomy, to provide coverage over the implant. However, it was quickly learned that there was a high risk of implant exposure from wound dehiscence. The implant was too heavy for the delicate mastectomy skin. As a result, tissue expanders were developed ( Fig. 2 ).

Tissue expanders are placed beneath the pectoralis major muscles at the time of mastectomy. They are slowly inflated with saline over time, stretching the pectoralis major muscle until the intended breast size is achieved. The rate of expansion is adjusted per patient based on skin integrity and patient tolerance. The expanders are subsequently exchanged for a permanent, more natural appearing, implant a few months later as an outpatient. The nipple can be reconstructed at a third operation a minimum of 6 weeks later.

Cosmetic importance of the nipple-areola complex

Plastic surgeons recognized that the nipple-areola complex defines a breast as a breast and therefore defined a reconstructed breast mound. Reconstruction is performed using skin from the local area or donated from the groin area. Alternatively, the nipple-areola disk could be harvested at the time of mastectomy, with banking of the nipple in the patient‘s groin as a full-thickness skin graft and later replacing it on the reconstructed breast ( Fig. 3 ). Attempts to maintain the nipple in a tissue bank for future reimplantation resulted in poor viability of the preserved nipple-areola disk. However, whether banking in the groin or the biorepository, concerns about transplanting cancer contained within the preserved nipple started to appear in the literature ; thus, this practice fell out of favor. Focus shifted back to improving the techniques of nipple reconstruction and investigating the psychological importance of having recreation of a nipple on a reconstructed breast mound.

Autologous tissue flap reconstruction and skin-sparing mastectomy

In the 1980s, new methods of breast reconstruction were being developed, namely autologous tissue transfers. These modalities (latissimus dorsi and transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous flaps) offered an alternative to expander/implant reconstruction and provided the ability to create a larger breast mound size, with ptosis if needed ( Figs. 4 and 5 ).

In 1984, Toth and Lappert introduced the concept of the skin-sparing mastectomy.

- •

A skin-sparing mastectomy removes the entire breast and provides access to the axilla for lymph node removal, but preserves a minimum of 80% of the native breast skin, but always removes the nipple-areola complex. By preserving the maximal amount of breast skin, the breast surgeon provides the patient with an envelope that is the same size, color, contour, and ptosis as her original breast. These investigators also recommended avoiding incisions in the upper part of the breast, which could affect cosmesis ( Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6

Common incision used for a skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction.

- •

Initial concerns regarding the oncologic safety of preserving additional skin were quelled by studies proving the technical feasibility and low local recurrence rate. With all types of mastectomy, if the undersurface of the remaining native breast skin and the anterior surface of the pectoralis major muscles is scraped, approximately 1 g of normal breast epithelial cells could be identified. Thus, the local recurrence rates were no different between skin-sparing and non–skin-sparing mastectomy.

- •

Skin-sparing mastectomies are standard of practice.

Nipple areolar preservation or reconstruction

Aside from Petit in the eighteenth century, preserving the nipple-areola complex went against surgical dogma. Several studies (1970–1990) reported unsuspected nipple involvement in 6% to 58% of mastectomy specimens. All studies took a cylinder of tissue encompassing the nipple-areola complex and the tissue up to 20 mm deep to it ( Table 1 ).

| Author, Year | Number of Specimens | Nipple Involvement (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Smith, 1976 | 541 | 12 |

| Parry, 1977 | 200 | 8 |

| Andersen, 1979 | 40 | 50 |

| Lagios, 1979 | 149 | 30 |

| Wertheim, 1980 | 1000 | 23 |

| Quinn, 1981 | 45 | 25 |

| Morimoto, 1985 | 141 | 31 |

| Luttges, 1987 | 166 | 38 |

| Santini, 1989 | 1291 | 12 |

| Menon, 1989 | 33 | 58 |

| Verma, 1997 | 26 | 0 |

| Vyas, 1998 | 140 | 16 |

| Laronga, 1999 | 286 | 6 |

In current practice, 20 mm of tissue is not left on the nipple flap during a nipple-sparing mastectomy, but rather, it is the same as the rest of the flap (ie, 3–5 mm). Using a 5-mm zone behind the nipple-areola complex as the definition for involvement of the nipple with a true occult second cancer, the incidence would be lower (<5%). Despite this knowledge, many surgeons still were not comfortable with the prospect of sparing the nipple and thus relied on the plastic surgeon to create a nipple.

Although there are many techniques to recreate a nipple, they all fall into 1 of 3 groups.

- •

The first method is called composite grafting, which entails borrowing tissue from a distant source (contralateral normal nipple, cartilage graft from the ear, skin from the groin area), use of various acellular dermal matrices, or use of fillers that can be injected/placed under the breast skin.

- •

The second approach uses local in situ breast skin flaps to recreate a projecting nipple with primary closure of the donor site.

- •

The final option, referred to as a skate flap, is a similar recreation of the nipple with local breast skin but rather than closing the donor site primarily, it uses a skin graft to cover the area that was borrowed from. Typically, this procedure manifests itself as a round graft mimicking an areolar disk.

Despite numerous advances in nipple reconstruction, loss of projection, diminished color variation, and asymmetry continued to plague the plastic surgeon.

Birth of the areola-sparing mastectomy

In the late 1990s, surgeons began exploring the option of areola-sparing mastectomy. The areola disk is a skin appendage and not breast tissue. Therefore, it cannot make a de novo breast cancer. Akin to skin-sparing mastectomy, the technique needed to be defined and more specifically, what the areola disk would be used for. The 2 options were:

- •

Leave the areola disk in situ and create a nipple using donor skin from the autologous tissue transfer

- •

Use the areola disk to create a nipple, and then later, tattoo the areola disk around the newly created nipple

The areola made a natural appearing nipple and did a better job maintaining its projection than recreating a nipple using the donor skin, especially if the donor skin was used at the initial reconstruction operation ( Fig. 7 A, B ). On the down side, the color tones and pigmentation within the areola are typically variegated and highly individual, defying exact match by even the most skillful tattoo artist (see Fig. 7 C).