Nipple Disorders

The nipple can be affected by a variety of inflammatory and neoplastic conditions that affect the skin, cutaneous appendages, and subcutaneous tissue elsewhere in the body. In addition, accessory (supernumerary) nipples may be found anywhere along the milk lines, which in embryonic life extend from the axilla to the groin. These accessory nipples consist microscopically of normal nipple components, including lactiferous ducts and smooth muscle, and may also contain mammary glandular tissue in the deep dermis.

The remainder of this chapter will focus on the most clinically important disorders of the nipple. Normal anatomy and histology of the nipple is discussed in Chapter 1.

SQUAMOUS METAPLASIA OF LACTIFEROUS DUCTS (SMOLD)

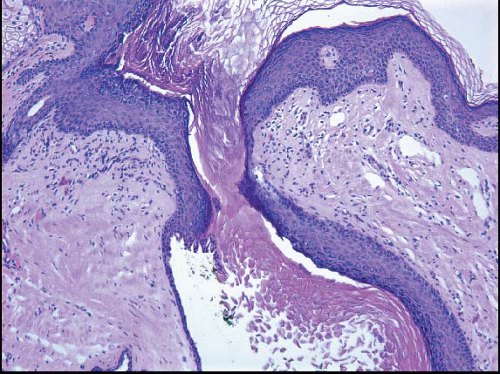

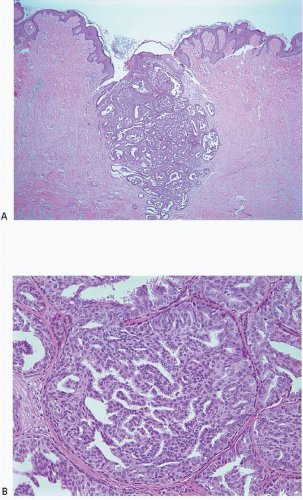

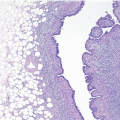

The keratinizing squamous epithelium of the skin normally invaginates into the nipple duct orifices for approximately 1 to 2 mm (Fig. 15.1, e-Fig. 15.1). However, if this epithelium extends more deeply into a nipple duct, keratin may accumulate, filling and obstructing the duct and creating a lesion analogous to an epidermal inclusion cyst. Rupture of the duct will result in the extrusion of keratinaceous debris into the stroma, eliciting a foreign body giant cell inflammatory reaction. Secondary bacterial colonization and infection may occur. This condition, known as SMOLD (also known as Zuska disease and recurrent subareolar abscess), presents as a red and painful mass near the nipple that may be interpreted clinically to be an abscess.1 It may occur at any age and is highly associated with a history of smoking. Antibiotic therapy and/or incision and drainage procedures are generally ineffective. Treatment requires complete excision of the affected duct or ducts, with

wedge resection of the nipple. Failure to adequately excise the area may result in multiple recurrences or formation of a fistulous tract.1,2

wedge resection of the nipple. Failure to adequately excise the area may result in multiple recurrences or formation of a fistulous tract.1,2

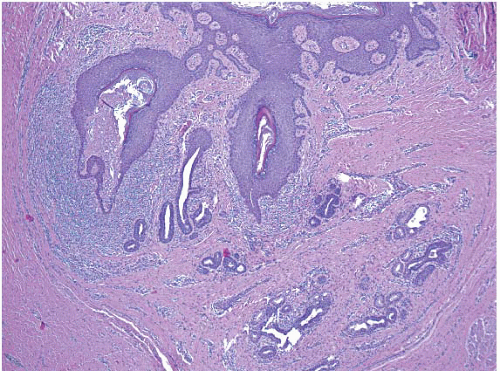

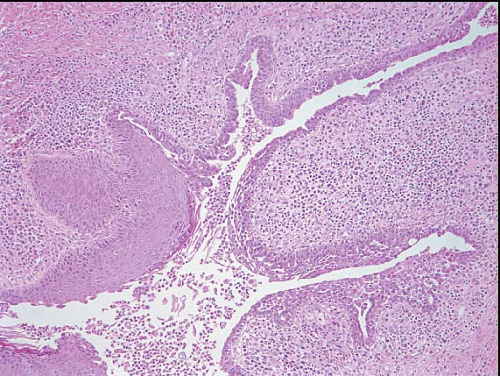

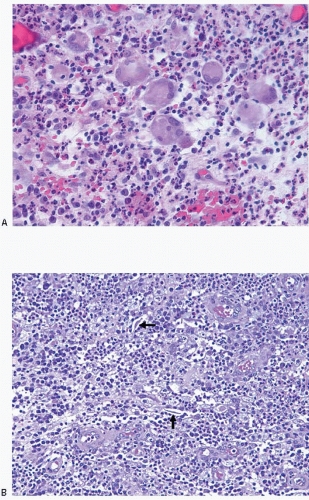

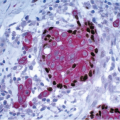

The initial surgical procedure in patients with SMOLD is often incision and drainage of a presumptive abscess. Specimens from this type of procedure typically consist of fragments of subareolar breast tissue, with or without subcutaneous tissue and/or skin, and show a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and foreign body giant cell reaction. Areas of abscess formation may be present. The findings of inflammation and foreign body giant cell reaction are not specific. However, in the appropriate clinical context, these findings should raise the suspicion of SMOLD and should prompt careful histologic evaluation for the presence of keratinaceous debris within the inflammatory infiltrate and for ducts with squamous metaplasia and/or intraluminal keratin, which are the defining features of this disorder. Diagnostic features of SMOLD are more often seen in subsequent excision specimens than in specimens from incision and drainage procedures because more tissue is available for histologic examination (Figs. 15.2, 15.3 and 15.4, e-Figs. 15.2, 15.3, 15.4 and 15.5). The key features of SMOLD are summarized in Table 15.1.

TABLE 15.1 Key Features of Squamous Metaplasia of Lactiferous Ducts | |

|---|---|

|

NIPPLE ADENOMA

Nipple adenoma is a relatively uncommon entity that may be mistaken for carcinoma. The condition has also been called florid papillomatosis of the nipple, florid adenomatosis, subareolar duct papillomatosis, and erosive adenomatosis. It is most common in the fifth to six decades, but may be seen in women of any age and also occurs in men. Patients present with soreness, ulceration, and swelling of the nipple and occasionally with discharge; the clinical presentation may simulate Paget disease.3,4

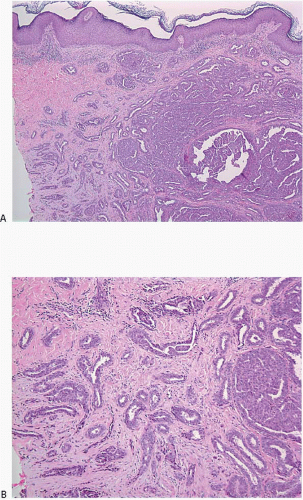

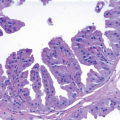

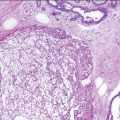

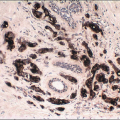

The gross appearance is usually that of an ill-defined, firm nodule. Microscopically, nipple adenomas have a wide range of histologic appearances. In general, these lesions are characterized by a relatively circumscribed proliferation of benign glands and ducts in a variably fibrotic stroma (Fig. 15.5, e-Fig. 15.6). The glands may grow in an adenosis-like pattern characterized by a proliferation of relatively simple glands or they may be expanded and distorted by prominent papillary hyperplasia and/or usual ductal hyperplasia. The hyperplasia sometimes has gynecomastoid features, and foci of necrosis may be seen (Figs. 15.6, 15.7 and 15.8, e-Figs. 15.7, 15.8, 15.9 and 15.10). Apocrine metaplasia or squamous metaplasia may be present. Stromal sclerosis around glands or in association with papillary intraductal hyperplasia may result in epithelial entrapment and distortion and a pseudoinfiltrative pattern. However, as with other benign lesions, the glands and ducts of nipple adenomas are surrounded by a myoepithelial cell layer. Rosen and Caicco4 described three distinct growth patterns of nipple adenoma: adenosis, papillomatosis, and sclerosing papillomatosis. However, these are often mixed and do not appear to have any prognostic significance. Of note, glandular epithelium may extend onto the surface of the nipple, replacing the squamous epithelium and producing clinically an erythematous, eroded appearance that may be mistaken for Paget disease (Fig. 15.9, e-Fig. 15.11). The key histologic features of nipple adenoma are summarized in Table 15.2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree