Fig. 9.1

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: stage at diagnosis

Histological Features and World Health Organization (WHO) Classification 2010

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are considered to be epithelial neoplasms with neuroendocrine differentiation. However, for many years, these tumors were defined as “carcinoid” since Siegfried Oberndorfer in 1907 coined, for the first time, the term “karzinoide” (“cancer-like”) for a tumor in the small intestine. NETs can arise in many organs, but most NETs arise from the gut or bronchopulmonary system. GEP-NETs represent a heterogeneous group of relatively uncommon neoplasms originating from the pancreas or gastrointestinal tract: gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (GI-NETs). The clinical outcome of these tumors is extremely variable, ranging from indolent disease to highly aggressive disease. Despite appreciable behavioral differences, pNETs and GINETs, are considered to belong to the same family of tumors (NETs) because they both express neuroendocrine markers.

The diagnosis of NET is based primarily on morphology and immunohistochemical expression of the general markers of neuroendocrine differentiation. Cytological features vary from round-to-ovoid cells with slightly granular cytoplasm and nuclei with dispersed chromatin (“salt and pepper”) to small or large neuroendocrine cells. The former are typical of less aggressive tumors; the latter are associated with an adverse outcome. The more common architectural features of NETs are trabecular, nested, glandular or mixed. These patterns are frequently found in less aggressive NETs, whereas aggressive NETs show irregular patterns with areas of necrosis. Among the several immunohistochemical markers of neuroendocrine differentiation available, synaptophysin (a small-vesicle-associated marker) and chromogranin (a large secretory granuleassociated marker) are considered to be more useful for the diagnosis of NETs.

The clinical behavior of NETs is related to several characteristics: anatomic location as well as the grading and stage of disease. In 2000, the WHO proposed a clinicopathological classification to stratify NETs according to malignant potential, i.e., well differentiated (benign or with uncertain malignant potential); well-differentiated (low-grade malignant); or poorly differentiated (high-grade malignant). This categorization was based on: tumor size, extent of organ-specific invasion, lymph node or distant metastases, angio-invasion, functional status, and proliferation index. This classification showed NETs arising at different anatomical sites with different biological and clinical behavior. This statement was confirmed and clearly defined by the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) that in 2006 and 2007 proposed a site-specific tumor/node/metastasis (TNM) staging system for NETs.

Moreover, ENETS proposed a histological grading system based on mitotic activity and the proliferation index that was applicable for all anatomic sites of the digestive system. The same histological grading system for NETs was adopted in 2010 by the WHO [3–14]. Therefore, at the present time, neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) of the pancreas are classified by histology based on the same criteria established for NENs arising at other sites by ENETS and WHO. Two main categories can be identified: NETs and neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC). NETs are well or moderately differentiated tumors that are divided into two grades: G1 or low-grade (mitoses <l2 per10 high power fields and/or Ki-67 labeling index ≤2%) and G2 or intermediate grade (mitoses of 2.20 per 10 high power fields and/or Ki-67 labeling index of 3–20%). NECs are poorly differentiated tumors (mitoses <20 per 10 high power fields and/or Ki-67 labeling index <20%). NECs are highly aggressive tumors that rapidly metastasize, whereas NETs can present with indolent or highly malignant behavior (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1

Grading system for neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas by the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) and World Health Organization (WHO)

ENETS/WHO Grade | Mitotic Count (10 HPF) | Ki-67 Index (%) | Clinical Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

Low (G1) | <2 | ≤2 | Variable |

Intermediate (G2) | 2–20 | 3–20 | Variable |

High (G3) | >20 | >20 | Highly aggressive |

However, other cutoff values have been proposed as prognostic indicators. For p-NETs, it has been demonstrated to be a Ki-67 index >5% (15). Although several cutoff values have been proposed, two parallel systems for the staging of p-NETs are available, i.e., the staging system by the ENETS and the WHO. These systems are different given the fact that, although they use the same TNM terminology, they refer to different extents of disease. This can lead to confusion and limits the possibility of comparing the results of clinical trials (Table 9.2). Recently, a large international cohort study compared the accuracy and the usefulness of the TNM staging systems set by ENETS and WHO in a series of 1,072 NENs of the pancreas. This study demonstrated that the ENETS TNM staging system was more accurate and superior in performance than that set by the WHO TNM staging system [16].

Table 9.2

Comparison of the definition for the T category in the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) and World Health Organization (WHO) Tumor/Node/Metastasis (TNM) staging systems

T1 | Confined to the pancreas, <2 cm | Confined to the pancreas, <2 cm |

|---|---|---|

T2 | Confined to the pancreas, 2–4 cm | Confined to the pancreas, >2 cm |

T3 | Confined to the pancreas, >4 cm, or invasion of duodenum or bile duct | Tumor extends beyond the pancreas |

T4 | Invasion of adjacent organs or major vessels | Tumor involves the celiac axis or superior mesenteric artery |

Treatment

The management of pNETs requires a multidisciplinary approach. Moreover, given the rarity of these tumors, patients should be treated at highly specialized centers. A recent analysis showed a significant difference in survival between two population based-studies (Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program (SEER) and National Cancer Data Base (NCDB)) and two institutional databases of centers with experience in the treatment of NETs. Among stage- IV patients, 5-year survival rates were 15% and 19% in the SEER and NCDB vs 55% and 57% in the two institutional databases, respectively (Table 9.3). It seems reasonable to suggest that this significant difference in survival could be due to the better care of patients treated in specialized centers [17]. Resection remains the mainstay for the treatment of early-stage disease and hepatic metastasis in selected cases. Medical treatment has a key role in the manage- ment of advanced-stage pNETs, allowing symptom control and tumor-mass reduction.

Table 9.3

Discrepancies in the survival of patients with neuroendocrine tumors across studies

TNM Stage | Institutional Analysis (US) | Population Database (SEER) |

|---|---|---|

I | 100% | 62% |

II | 88% | − |

III | 85% | 53% |

IV | 57% | 20% |

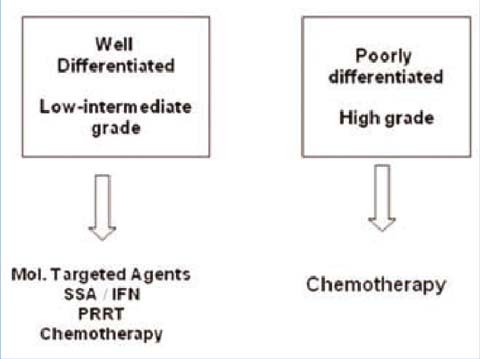

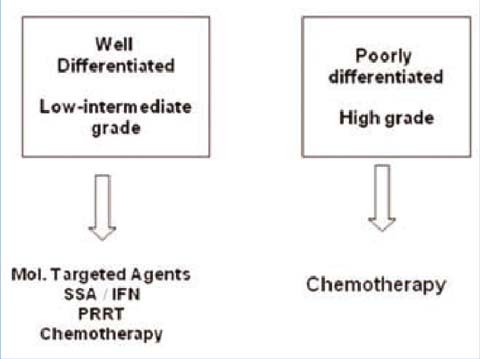

Non-surgical therapeutic approaches include medical treatments, interventional radiology methods and radiotherapy. Medical approaches are represented by chemotherapy (CT), molecular-targeted agents (everolimus and sunitinib), hormonal therapy (somatostatin analogs (SSAs)) and immunomodulating agents (interferon (INF)). Interventional radiology methods include: radiofrequency ablation, transarterial chemoembolization, transarterial radioembolization and nuclear medicine methods (e.g., polypeptide radionuclide receptor therapy (PPRT)). External beam radiotherapy has a palliative role, especially in the treatment of bone metastasis (Fig. 9.2).

Fig. 9.2

WHO classification 2010 and treatment options

SSAs and INF

The neuropeptide somatostatin is one of the major regulatory peptides in the central nervous system and digestive tract. Somatostatin acts by inhibiting the secretion of various hormones and peptides. For this reason, SSAs remain the mainstay of treatment of symptomatic GEP-NETs. Due to their short half-life (<2 min), native SSAs are not currently used. Nevertheless, the SSAs long-acting octreotide and lanreotide autogel are characterized by long-acting formulations which allow monthly administration. Long-acting octreotide and lanreotide autogel bind mainly to the somastostatin receptor subtypes 2 (SSTR2) and 5 (SSTR5) and provide symptomatic as well as biochemical responses in ≤75% of patients [18]. Recently, pasireotide (a SSA with high affinity for all types of SSTRs) was approved for acromegaly treatment. Although early data suggest that this drug is effective in patients affected by NETs not responsive to currently available SSAs, the treatment of NETs with pasireotide is restricted in clinical trials [19]. SSAs are safe, well-tolerated and easy to use. In retrospective experiences, SSAs provided a 5% partial response (PR) and 50% stable disease (SD).

Rinke et al. randomized 85 treatment-naive patients with metastatic well differentiated tumors in the midgut to receive placebo or octreotide LAR 30 mg monthly until tumor progression. The primary endpoints were time to progression (TTP) and response rate (RR). The study was designed for the enrollment of 162 patients in 18 academic centers in Germany, but it was stopped early after the enrollment of 85 patients (43 received octreotide LAR 30 mg and 42 received placebo) due to the results of the interim analysis. In fact, median TTP was 15.6 months in the octreotide LAR group vs 5.9 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio (HR) 0.34; 95% confidence interval (CI), 20–0.59; p=0.000072) [20]. The authors demonstrated, in a preplanned subgroup analysis, that patients with low (0% to 10%) liver involvement and resected primary tumor benefited most from the treatment (HR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.08–0.40; and HR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.07–0.36, respectively). This prospective trial suggested an anti-tumor activity of SSAs in patients with well-differentiated midgut tumors. There is no prospective evidence supporting the anti-tumor activity of SSAs in pNETs but, in our opinion, the first-line treatment of patients affected by wellor moderately differentiated, low proliferating pNETs should consist of SSAs rather then chemotherapy. The Study of Lanreotide Autogel in Non-functioning Entero-pancreatic Endocrine Tumors (CLARINET) is an ongoing randomized trial which aims to define this issue. In this study, patients with G1 and G2 nonfunctioning pNETs and midgut NETs are randomized to lanreotide autogel (120 mg) monthly or to placebo. The primary endpoint is TTP. The enrolment is complete and data are expected within the next months.

INFα monotherapy has revealed similar efficacy to SSAs for controlling symptoms and inducing biochemical responses (80% of patients). Nevertheless, INFα has a different tolerability profile, with more frequent high-grade toxicity, such as flu-like syndrome, fatigue, weight loss, polyneuropathy, myositis, thrombocytopenia, anemia, leukopenia and hepatotoxicity as well as other side effects [21]. There is evidence that combination therapy (interferon alpha plus SSAs) does not increase RR but leads to a significantly lower risk of progression compared with SSAs alone [22].

Chemotherapy

The role of chemotherapy in the treatment of pNET is controversial. Based on retrospective studies, systemic chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide is the standard of care for poorly differentiated NECs with Ki-67 >20% (Fig. 9.1). This platinum-based combination provides a high RR, but the prognosis of this group of patients is poor (median survival, ≈20 months) [23, 24]. The recently published NORDIC NEC study retrospectively analyzed 305 patients affected by metastatic GI-NECs or unknown primary tumor with gastrointestinal metastases [25]. In this large retrospective study, patients with Ki-67 <55% were less responsive to platinum-based chemotherapy but survived longer than patients with Ki-67 >55%. The authors concluded that Ki-67 <55% represents a favorable prognostic factor and a negative predictive factor for the efficacy of platinum- based chemotherapy. Therefore, different from the present WHO classification, we should not consider GI-NECs as a single disease.

Several studies suggest that pNETs are responsive to chemotherapy (Tables 9.4 and 9.5).

Table 9.4

Chemotherapy in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: randomized clinical trials

Regimen | Tumor Type | N | RR % | TTP months | OS months | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Streptozocin/5FU streprozocin/cyfaxan | Mixed carcinoid and pancreas | 42 | 33 | – | – | Moertel et al., 1979 |

47 | 26 | – | – | |||

Adriamicina/streprozocin/5FU | Mixed | 86 | 21 | 6 | 12 | Engstrom et al., 1984 |

86 | 22 | 7 | 16 | |||

Streptozocin/ doxorubicin vs streprozocin/5FU | Pancreas only | 36 | 69* | 20* | 26.4* | Moertel et al., 1992 |

33 | 45 | 6.9 | 16.8 | |||

Streptozocin/5FU vs doxorubicina/5FU | Mixed carcinoid and pancreas | 88 | 16 | 5.3 | 24.3* | Sun et al., 2005 |

88 | 15.9 | 4.5 | 15.7 |

Table 9.5

Chemotherapy in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: selected non-randomized trials

Regimen | Tumor Type | N | RR % | TTP mo | OS mo | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5FU/doxorubicin/CDDP | Mixed | 74 | 15 | – | – | Rougier et al. [56] |

Carboplatin | Mixed | 42 | 5 | – | – | Saltz et al. [57] |

DTIC/5FU/epirubicina | Mixed | 38 | 18 | 5 | – | Di Bartolomeo et al. [58] |

5FU/DTIC | Mixed | 82 | 24 | 21 | 38 | Bajetta et al. [59] |

Capecitabine/oxaliplatin | Mixed | 40 | 28 | 18 | 32 | Bajetta et al. [60] |

Temozolomide/thalidomide | Mixed | 79 | 25 | 13.5 | – | Kulke et al. [32] |

Temozolomide | Mixed | 36 | 14 | 7 | 16 | Ekeblad et al. [31] |

Temozolomide/capecitabine | Pancreas | 30 | 70 | 18.0 | – | Strosberg et al. [33] |

Streptozotocin is an alkylating agent that has been studied in combination with 5-Fluorouracil (5FU) and doxorubicin in well-differentiated NETs. Notably, randomized trials comparing first-line chemotherapy vs best supportive care (BSC) are lacking. In a randomized trial, streptozotocin plus doxorubicin compared with streptozotocin plus 5FU significantly improved the RR (69% vs 45%), progression-free survival (PFS) (20 months vs 6.9 months) and OS (26 months vs 18 months) [26]. On the basis of these results, streptozotocin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of pNETs. Nevertheless, the authors of this trial used non-standard criteria for response evaluation, and assessed biochemical response rather than objective tumor response as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria. Moreover, in two retrospective analyses, streptozotocin plus doxorubicin showed mild anti-tumor activity with a RR of 10% [27, 28]. Dacarbazine monotherapy has been evaluated in a Phase II study enrolling 50 patients with pNETs. In this trial, dacarbazine provided a RR of 34% and OS of 19.3 months [29]. Nevertheless, due to its toxicity profile, dacarbazine is not frequently used in the treatment of pNETs. Temozolomide is an alkylating agent developed as an oral and less toxic alternative to dacarbazine [30]. In a retrospective analysis, Ekeblad et al. evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of temozolamide monotherapy in advanced NETs. The RR was 14% and SD was noted in 53% with a global disease control rate (DCR) of 67% [31]. The median TTP was 7 months. With respect to RR, 1 patient among the 14 affected by GI-NETs and 5 patients among the 11 affected by pNETs showed a radiological response. This observation supports the fact that well-differentiated pNETs are more responsive to systemic chemotherapy than NETs arising from the stomach, small intestine and large intestine. Temozolamide has been studied in patients affected by advanced NETs in combination with different anti-cancer drugs such as thalidomide, capecitabine and bevacizumab. In a Phase II trial, 41 patients affected by well-differentiated NETs were treated with a temozolamide plus thalidomide combination. In this trial, the authors observed a 45% RR (including 1 complete response (CR)) among the 11 patients affected by pNET [32]. The capecitabine and temozolamide combination is also effective in pNETs. In a single-institution retrospective experience, 30 patients with unresectable/metastatic pNETs were treated with capecitabine and temozolamide. The authors observed a RR of 59% and a CR in 6% [33].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree