Chromogranin A is a large protein that is produced by all cells deriving from the neural crest. The function of chromogranin A is not known, but it is produced in very significant quantities by NET cells regardless of their secretory status.

5-HIAA is the main metabolite of serotonin. The 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA is raised in 70% of patients with midgut carcinoid and some patients with foregut carcinoid. Urinary excretion of 5-HIAA may be affected by certain foods and drugs if they are taken just before collection of the urine sample (Box 32.1). Tachykinins (neurokinin A and B) are raised in midgut carcinoids.

Specific endocrine tests should be requested depending on which syndrome is suspected.

Suspected insulinoma

In patients presenting with acute hypoglycaemia, serum should be taken quickly for blood glucose, insulin and C-peptide levels prior to giving glucose. Low C-peptide and high insulin levels indicate exogenous insulin. High C-peptide and insulin levels indicate endogenous insulin, for example either stimulated by surreptitious sulphonylurea ingestion or released by an insulinoma.

Patients with a history suggestive of hypogly-caemic episodes should be investigated with a 72-hour fast, allowing unlimited non-caloric fluids.

Elevated plasma insulin and C-peptide levels in the presence of hypoglycaemia (laboratory glucose < 2.2 mmol/L) are diagnostic. A plasma glucose level of less than 2.2 mmol/L is achieved by 48 hours of fasting for over 95% of insulinomas. If no hypoglycaemia is achieved by the end of the fast, the sensitivity can be further increased by exercising the patient for 15 minutes. The fast is terminated after the exercise period, or prior to this if hypoglycaemia is achieved (but only after samples for insulin and C-peptide have been taken).

Patients with ‘factitious hypoglycaemia’ (due to exogenous insulin) do not have elevated C-peptide levels. All patients should also have simultaneous urine samples for sulphonylurea analysis, which must be shown to be negative for the diagnosis of insulinoma.

The differential diagnosis of fasting hypoglycae-mia in summarized in Box 32. 2.

A rare cause of fasting hypoglycaemia is the secretion of an incompletely processed form of insulin-like growth factor 2 (‘big-IGF-2’) by mesen-chymal tumours. These patients have suppressed insulin levels, low IGF-1 and a raised ratio of IGF-2 to IGF-1.

Suspected gastrinomas

Investigations for suspected gastrinomas include fasting gastrin level (raised basal serum gastrin) and gastric secretion studies (high gastric acid secretion).

To measure gastrin in a patient with a suspected gastrinoma, the patient must be off proton pump inhibitors for at least 2 weeks and off histamine 2-blockers for at least 3 days. Caution, however, is required if the clinical likelihood of a gastrinoma is high since there is a high risk of peptic ulcer perforation when medical therapy is stopped for the gastrin test. Even on proton pump inhibitors, very high gastrin levels (> 250 pmol/L) are indicative of gastrinoma, and repeat testing off therapy should not be recommended.

Differential diagnoses, which include atrophic gastritis, hypercalcaemia and renal impairment, may be excluded by measuring basal acid output. Spontaneous basal acid outputs of 20–25 mmol per hour are almost diagnostic and over 10 mmol per hour are suggestive. If the test results are equivocal, the secretin test is helpful: a rise in gastrin of more than 100 pmol/L (instead of the normal fall) in response to intravenous secretin has a sensitivity of 80–85% for gastrinoma.

Imaging

The optimum imaging modality depends on whether it is to be used for detecting disease in a patient suspected of a NET or for assessing the extent of disease in a known case.

For detecting the primary tumour, a multimo-dality approach is best and may include computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, soma-tostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS), endoscopic ultrasound (for pancreatic NETs, with a 94% sensitivity for detecting insulinomas) and visceral angiography (helpful for subcentimetre tumours, where a tumour blush is seen) plus calcium stimulation (see below). For assessing secondaries, SRS is the most sensitive modality. When a primary tumour has been resected, SRS may be indicated for follow-up. SRS has a sensitivity of up to 90% and a specificity of 80% (excluding insulinomas), and has a sensitivity of 10–50% for insulinomas.

With pancreatic tumours, the surgeon requires as much information as possible regarding location.

Selective angiography with secretagogue injection into the main pancreatic arteries allows angiographic and biochemical localization. In this procedure, the main pancreatic arteries (gastroduodenal, superior mesenteric, inferior pancreatico-duodenal, splenic) are cannulated separately and examined for a ‘tumour blush’.

Calcium (acting as a secretagogue) is injected into each of these arteries individually, and venous samples are collected from the hepatic vein for biochemical analysis of the suspected hypersecreted hormone (e.g. gastrin, insulin). In the presence of a tumour, the hormone levels double after 30 seconds, whereas the normal effect is a reduction in levels. The hepatic artery is always cannulated at the end of the procedure. A rise in hormone levels detectable in the hepatic vein after calcium injection into the hepatic artery is diagnostic of liver metastases.

Treatment

All cases must be discussed and managed within a multidisciplinary team. The choice of treatment depends on the symptoms, stage of disease, degree of uptake of radionuclide and histological features of the tumour.

Surgery is the only curative treatment for NETs and should be offered to patients who are fit and have limited disease (i.e. primary tumour with or without positive regional lymph nodes).

For patients who are not fit for surgery, the aim of treatment is to improve and maintain an optimal quality of life. Treatment choices for non-resectable disease include somatostatin analogues, chemotherapy, radionuclides and ablation therapies. External beam radiotherapy may relieve bone pain from metastases.

Surgical treatment

Conduct of surgery is dependent on the method of presentation and stage of disease. Surgery should only be undertaken in specialist units. Patients presenting with suspected appendicitis, intestinal obstruction or other gastrointestinal emergencies are likely to require resections sufficient to correct the immediate problem. Once definitive histopathology has been obtained, a further more radical resection may have to be considered.

Where abdominal surgery is undertaken and long-term treatment with somatostatin analogues is likely, cholecystectomy should be considered (see the side-effects of somatostatin analogues, below). Surgery also has a place in palliation when tumour bulk is too extensive for curative resections.

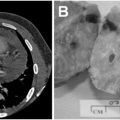

Liver metastases

Surgery should also be considered in those with liver metastases and potentially resectable disease. Cryosurgery, where a cryoprobe is inserted surgically into each metastasis, causing tumour necrosis, has been used in the palliation of liver metastases. Liver transplantation has been performed in selected patients with numerous liver metastases, with survival of about 50% after 1 year.

Preparation

A potential carcinoid crisis should be prevented by the intravenous infusion of octreotide at a dose of 50μg per hour for 12 hours prior to and at least 48 hours after surgery. It is also important to avoid drugs that release histamine or activate the sympathetic nervous system. Other prophylactic measures for other NETs include glucose infusion for insulinomas, and proton pump inhibitors and intravenous octreotide for gastrinomas.

Medical treatment

Medical treatment has to be initiated for symptom control until curative surgical treatment is performed, or if surgery is not indicated. Box 32.3 summarizes the medical treatments for the various hypersecretion syndromes.

Somatostatin analogues

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree