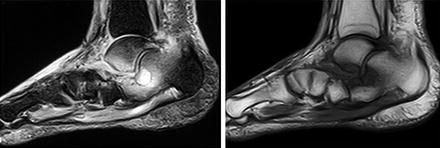

Figure 11.1

Inflammation of the foot and lower leg in the acute phase of Charcot foot (left). Residual deformity apparent in the same leg after the swelling has regressed (right)

Once the condition is suspected, the person should be referred promptly to an expert in the field and should have a plain x-ray (taken weight-bearing to exaggerate any radiological signs of loss of integrity of the skeleton of the foot). If the x-ray is normal and the disease is still suspected, the person should have an MRI of the foot as soon as possible and should remain non-weight bearing until it is done (Fig. 11.2). The MRI will highlight inflammation of both soft tissue and bone, even in the absence of overt fracture or dislocation. A CT scan may also highlight small fractures that are not apparent on a plain x-ray. It is possible that newer imaging techniques will prove to have added diagnostic value.

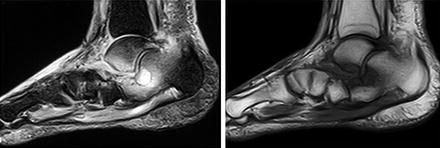

Figure 11.2

The MRI appearance of Charcot foot in the acute phase, with inflammation of the bone marrow and soft tissue being apparent as enhancement on the left (T2-weighted) image, and as suppression on the right

Treatment

There is no specific treatment that has been proved to be of benefit. Anti-inflammatory agents could theoretically limit the inflammatory process, but they have never been formally assessed in this condition. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents would also be contraindicated in people with renal disease. In the absence of any specific therapy, there is only one therapeutic option available, and that is immobilisation of the foot (called “off-loading”). Immobilisation (which should ideally be achieved with a non-removable, below knee fibreglass cast) has two aims: (1) to interrupt the cycle of persistent inflammation by splinting the foot, and (2) to protect the foot from traumatic injury at a time when the bones and joints are susceptible.

When an inflamed foot is immobilised in a fibreglass cast, the inflammation settles within days. Indeed, the inflammation and soft tissue swelling settle so quickly that the cast will usually need to be replaced within a week because it will no longer fit the foot sufficiently snugly. In cases of doubt, this rapid resolution of inflammation with immobilisation provides strong suggestive evidence supporting the diagnosis. In established disease, casts need to be changed each 1–3 weeks until the disease enters remission. This frequent change of cast also enables the foot to be frequently checked – to ensure that its condition of the foot has not deteriorated from, for example, ulceration caused by rubbing.

Casting should be continued until the Charcot process is thought to have entered remission. Remission may be judged simply by regression of the clinical signs of residual inflammation (including comparison of skin temperature on the two sides) but there are no other objective measures. Repeat MRI may give an indication of resolution of bone marrow oedema but it is expensive. Overall, casting is continued for a period of months. For reasons that are not clear, the reported duration of casting may vary from less than 6 months (reported in the USA and Denmark) to 12 months or more (reported in the UK).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree