Few interventions other than smoking cessation are known to be effective for cancer prevention.

Most cancer prevention studies are performed in younger populations. Caution should be used when generalizing these results to older populations.

While evidence of an association is strong, a causal link between obesity and cancer risk has not been established nor is there evidence that weight loss will reduce cancer risk.

Residential radon exposure is an overlooked environmental health risk.

The US Surgeon General estimates that within 10 years of quitting smoking the risk of lung cancer is reduced to half that of a current smoker.

Evidence regarding the benefit of screening interventions should be held to a high standard.

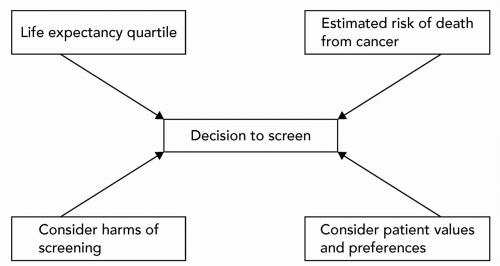

Screening in the geriatric patient requires balancing life expectancy with the anticipated benefits and risks of screening.

Randomized trials suggest that it takes at least 5 years before there is a mortality benefit from screening tests.

For most cancers, we lack clear evidence about when to stop screening.

There continue to be multiple acceptable options for colorectal cancer screening.

Despite the high mortality burden of lung and ovarian cancers, routine screening for these diseases is still not recommended.

There are roughly 10 million cancer survivors in the United States today, triple the number from 30 years ago.

Most cancer survivors are elderly.

Primary care physicians can, and should, provide routine cancer survivor care for their patients.

Most cancer surveillance regimens are fairly straightforward.

Guidelines for common cancers can help primary care physicians provide appropriate routine follow-up testing in cancer survivors.

TABLE 38.1 COMMON MALIGNANCIES IN THE GERIATRIC POPULATION (>65 Y) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

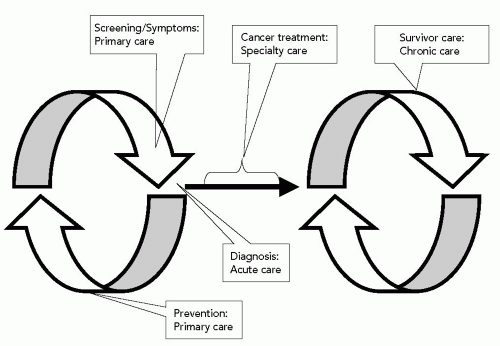

care continuum in Figure 38.1: (i) Cancer prevention services, (ii) cancer screening services, and (iii) routine care of the cancer survivor. Therefore, the section “Primary Prevention of Cancer” focuses on effective interventions that may reduce the risk of getting cancer. The section “Secondary Prevention: Screening for Cancer” presents evidence-based recommendations for prevention and screening services for common cancers, with consideration given to the appropriate use of screening in elderly populations with limited life expectancy. The section “Routine Care of the Cancer Survivor” is an acknowledgment of the relatively recent phenomenon of tremendous growth in the number of cancer survivors, most of whom are elderly. This section examines the role of the primary care physician in the care of the cancer survivor in the context of a chronic disease model and presents recommendations for routine follow-up care of survivors of common cancers.1,2

Surgeon General estimates that the risk of lung cancer is reduced to half that of a current smoker within 10 years of quitting.4 The time lag until health benefits accrue to recipients of secondhand smoke is unknown.

(Evidence Level B). However, given the higher risk of thromboembolic events and other harms or adverse effects in geriatric patients, the risks of tamoxifen use for primary prevention are likely to outweigh the expected benefits in this age-group.10 Consequently, any decision to use tamoxifen as primary breast cancer prevention in geriatric patients should not be pursued without prior consultation with an oncologist and thorough consideration of the particular patient.

TABLE 38.2 CRITERIA FOR APPROPRIATE SCREENING | |

|---|---|

|

Tumors tend to be less aggressive in older patients, so these patients are more likely to die from other comorbid conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease) rather than from cancer.

Increasing comorbidity and frailness from advancing age may make the diagnostic workup for a positive screen fraught with risk, or the rigors and side effects of definitive treatment may become unacceptable.

The potential harms of screening weigh more heavily, in view of points 1 and 2.

TABLE 38.3 RISK (PERCENTAGE) OF DYING FROM CANCER IN REMAINING LIFETIME FOR MEN AND WOMEN AT SELECTED AGES AND LIFE EXPECTANCY QUARTILESa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree