17 Neoadjuvant Therapy

Historical Perspective

Development of Systemic Treatment

Historically, the treatment of choice for breast cancer was a surgical one. William Stewart Halsted,1 at the time the head of surgery at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, suggested that breast cancer is a highly localized disease that can be cured by a radical local therapy. Unfortunately, radical surgeries did not prevent subsequent recurrences and breast cancer-related deaths. Schinzinger2 and Sir George Beatson3 proposed in the 19th century a relation between the removal of the ovaries and the regression of advanced breast cancer, suggesting a systemic component. Only decades later the idea of administration of systemic treatment during the early stages of the disease was introduced.4 The paradigm of breast cancer as a systemic disease was pushed forward by Bernhard Fisher who proposed that breast cancer metastasizes unpredictably and would be best treated with conservative local treatment and systemic therapy. With his colleagues at the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) he initiated innovative breast cancer trials starting in 1957.

| AC | doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide |

| CMF | cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil |

| CVAP | cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisone |

| FEC | 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide |

| NX | vinorelbine and capecitabine |

| TAC | docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide |

| VACP | vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone |

| VbMF | vinblastine, methotrexate with calcium leucovorin rescue, and fluorouracil |

Adjuvant systemic therapy is now administered to almost every woman with breast cancer and may include endocrine manipulations, chemotherapy, biologic therapy, or a combination. The most recent Oxford Overview of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Cooperative Group (EBCTCG), designed to summarize the benefits and toxicities of adjuvant chemotherapy was published in 2000 and included data from 102 clinical trials with 53,353 participants.5 The addition of any type of adjuvant chemotherapy reduces the risk of breast cancer recurrence and mortality rate by 22% and 15%, respectively, and reduces all-cause mortality rate by 13%. Anthracycline-based regimens provide additional benefit compared with the traditional cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5fluorouracil (CMF)-containing regimens. Women who received anthracycline-based regimens had a reduction in annual odds of breast cancer recurrence by 11% and all-cause death by 15% compared with those who received CMF-like regimens. More recently, taxanes have been added to anthracycline-based therapy in combination or a sequential manner and have further improved disease-free and overall survival.6

Chemotherapy has been traditionally used after the completion of breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy. Neoadjuvant therapy, also designated preoperative or primary chemotherapy, has been used for more than three decades to treat women with locally advanced breast cancer. Based on the success of adjuvant chemotherapy and the promising experiences with neoadjuvant therapy in older women or those with advanced disease, the neoadjuvant approach reached the center of interest for women with primary operable breast cancer. In these women, the initial goal was to improve overall survival based on the hypothesis that the administration of chemotherapy prior to the locoregional therapy could eradicate micrometastasis. Local control was a secondary objective that was recognized as a result of impressive tumor regression in some cases.7

Indications for Systemic Therapy

Before recommending the administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to women with primary operable disease, it is crucial to determine that chemotherapy is indeed indicated. Several organizations and international panels, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and the expert panel of St. Gallen, Switzerland, have been convened to create consensus recommendations regarding adjuvant systemic treatment for early breast cancer. Risk groups for recurrence are defined using prognostic factors, such as tumor size, grade, vascular invasion or age, as well as estrogen receptor (ER) and HER2 status. In the most recent St. Gallen symposium, three large categories of breast tumors were proposed including highly endocrine responsive, endocrine-nonresponsive and incompletely endocrine-responsive. Whereas nonresponsive disease is characterized by the absence of steroid receptors, differentiation between endocrine-responsive (ideally highly ER and progesterone receptor [PR]-positive) and incompletely endocrine-responsive is defined by the degree of ER and PR positivity. Furthermore, three risk categories were defined in St. Gallen: low, intermediate, and high. Depending on the risk categories and the endocrine responsiveness, endocrine therapy or chemo therapy alone or in combination is recommended.8 Overall, when a woman presents with clinical stage II or III breast cancer for which chemotherapy would be recommended as part of the multidisciplinary treatment, there may be advantages in the consideration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in some cases.

Objectives of Neoadjuvant Treatment

The emphasis of neoadjuvant therapy was initially the improvement of surgical options to obtain better local control in patients with locally advanced breast cancer. The therapy was designated induction chemotherapy and prospective studies confirmed that patients with inoperable locally advanced breast cancer who responded to the therapy could subsequently have a mastectomy. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women with primary operable disease was first investigated to improve disease-free or overall survival. In contrast to the primary aim of preoperative therapy in patients with locally advanced disease, the goal of multidisciplinary treatment in patients with operable breast cancer is to obtain freedom from disease.9

Over a dozen studies compared the same chemotherapy in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings. Mauri and colleagues10 performed a meta-analysis that included data from nine studies comparing adjuvant with neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a total of 3946 patients. The primary outcomes of the analysis were death, disease progression, distant disease recurrence, and locoregional disease recurrence. The investigators reported that neoadjuvant therapy was equivalent to adjuvant treatment in terms of survival and overall disease progression. The response to chemotherapy and the ability to perform breast conservation were prognostic indicators for 5-year disease-free survival and overall survival.11

Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy did not improve disease-free and overall survival compared with adjuvant treatment, the rate of breast-conserving therapy has been consistently superior.12 In the Mauri meta-analysis, seven trials reported that neoadjuvant therapy was associated with a higher rate of breast conservation, whereas one trial was associated with a borderline difference, and three other studies revealed no difference.10 However, there was a considerably high variability across these trials, which enrolled patients between 1983 and 1999. The studies included different treatment regimens, and surgery was not mandated in all of the trials after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

The first large preoperative trial was conducted by the NSABP. NSABP B-18 trial enrolled 1523 patients who were randomly assigned to four cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC) every 3 weeks before or after the definitive surgery. Compared with the adjuvant treatment group, 12% more lumpectomies were performed in the preoperative group.13 The European Cooperative Trial in Operable breast cancer (ECTO), randomized 1355 patients to four cycles of doxorubicin and paclitaxel followed by four cycles of CMF and found that breast preservation was feasible in 65% versus 34% (P < .001) for the administration of the therapy pre- and postoperatively, respectively.14

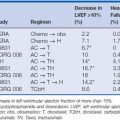

Other potential benefits of neoadjuvant chemotherapy have been proposed (Table 17-1). When chemotherapy is administered in the adjuvant setting, the effectiveness for an individual patient cannot be determined. In contrast, the response to neoadjuvant therapy may be appreciated after as few as one or two cycles. The early response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy can identify patients with a high probability of achieving a pathologic complete response (pCR)15 and thus serve as a predictor for pCR. Indeed, achieving a pCR correlated with improved disease-free survival and overall survival compared with those experiencing a partial or no response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy.16 Whereas overall survival (70% and 69%, respectively) and disease-free survival (55% and 53%, respectively) did not differ between the preoperative and the postoperative treatment group, a statistically significant improvement in survival rate occurred for patients who achieved a pCR compared with those with residual invasive tumor at the time of operation (85% versus 73% alive at 9 years).

Table 17-1 Potential Advantages and Disadvantages of Neoadjuvant Therapy

| Advantages |

| Disadvantages |

IHC, immunohistochemistry; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography.

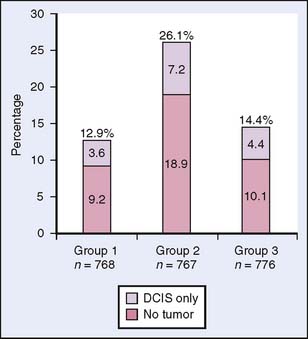

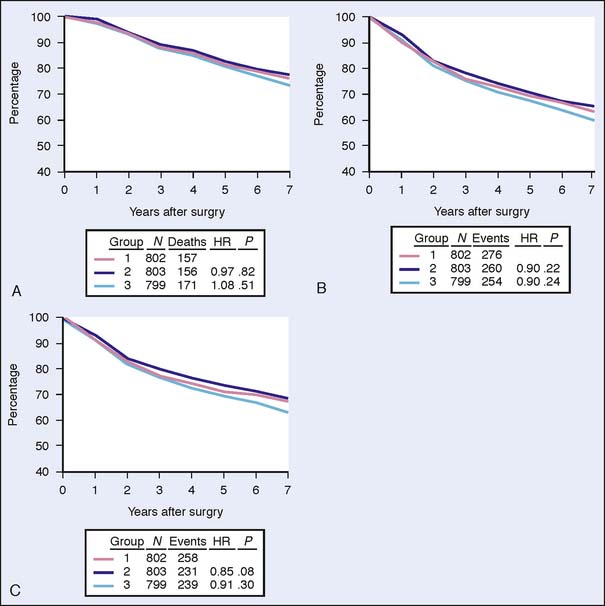

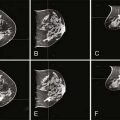

The results of the NSABP B-18 trial concerning pCR were confirmed by NSABP B-27.17 The NSABP B-27 trial was designed to evaluate the effects of adding docetaxel to AC preoperative treatment on response rate, disease-free survival, and overall survival. The 2411 participating patients were randomized to either AC followed by surgery (Group 1), AC followed by docetaxel and surgery (Group 2) or AC fol lowed by surgery and adjuvant docetaxel (Group 3). Although the addition of docetaxel had no statistically significant effect on disease-free survival and overall survival, the pCR rate increased from 13.7% to 26.1% (P < .001). Furthermore, the proportion of patients with negative nodes following neoadjuvant therapy was higher with the addition of docetaxel to AC compared with patients who received AC alone (50.8% versus 58.2%, respectively; P < .001). The B-27 trial results confirmed that response to chemotherapy is a significant predictive factor for disease-free survival and overall survival in individual patients. In addition, the rate of local relapses in this study was even lower when docetaxel was added to preoperative AC in the neoadjuvant group compared with relapse in the adjuvant group17 (Figs. 17-1 and 17-2).

Another important goal is to use neoadjuvant therapy as an in vivo sensitivity marker for tumor response. Assessment of tumor response is directly possible by clinical means and imaging as well as by biochemical measurements. It has been suggested that the primary tumor can be used as a monitor for treatment of micrometastasis. pCR after neoadjuvant therapy could thenbe a surrogate marker for the eradication of residual micrometastasis.9 Another hypothesis is that drug resistance may be minimized with early exposure to systemic therapy.18

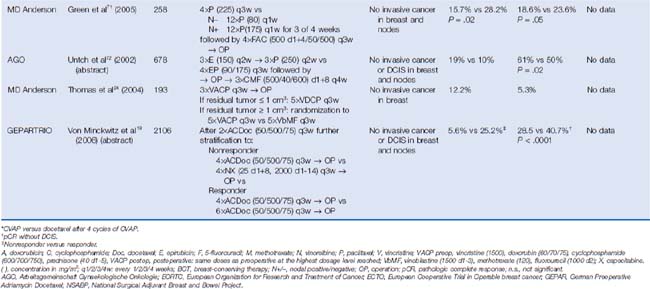

One model is to use early evaluation of response (e.g., following two cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy) to discriminate between patients with sensitive versus resistant tumors. The German Preoperative Adriamycin Docetaxel (GEPAR)TRIO trial randomized 2106 patients to two cycles of docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (TAC).15 Patients whose tumors responded were treated with another four or six cycles of TAC. Those whose tumor did not respond to the initial two cycles of TAC received either four additional cycles of TAC or a non–cross-resistant chemotherapy regimen with vinorelbine and capecitabine (NX). Whereas the pCR rate was 17.9% overall, patients responding to TAC reached a pCR rate of 22.9% compared with nonresponders treated with TAC (pCR rate 7.3%) or NX (pCR rate 3.1%). It is not yet clear whether a change in regimen might provide a survival benefit, because the data of the phase III trial are not sufficiently mature.19 However, an early response after two to three cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy was predictive of pCR, which is by itself an important indicator of long-term outcome in earlier studies.20

Another model uses the presurgical period for short-term administration of novel agents to evaluate biomarker modulation or to study mechanism of action. Finally, the use of new imaging methods and the ability to obtain serial tissue biopsies may assist in evaluating the treatment effects and make neoadjuvant therapy an attractive model to study mechanism of action of standard and novel therapies.

At the same time, the neoadjuvant approach may have potential disadvantages. One major concern was that an increased rate of breast conservation may be associated with higher locoregional recurrence rates. Particular attention must be given to women initially scheduled for mastectomy who were subsequently candidates for breast conservation following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Indeed, it has been demonstrated in NSABP B-18 that ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence rate was higher in women who were downstaged to a lumpectomy (15.4%) compared with those who were candidates for a lumpectomy before chemotherapy (9.9%).16

In the GEPARDUO Trial, 913 patients were treated preoperatively with either 8-week dose-dense doxorubicin and docetaxel or 24-week AC followed by docetaxel. The published details of the surgical procedures of 607 patients, including the retrospective collection and central review of surgical and pathologic reports, revealed that 70% of the patients were treated with breast conservation; however, 21.1% required reexcision (12.4%) or a mastectomy (8.7%).21

The Mauri meta-analysis reported a statistically significant higher risk for recurrence after neoadjuvant therapy.10 However, this effect was greater in trials in which patients received only radiation therapy without surgical removal of the primary tumor following the neoadjuvant systemic treatment, a strategy that is not recommended. As in primary surgery, negative margins are critical after preoperative therapy.

Neoadjuvant Treatment

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Initial studies of neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared the same chemotherapy regimen given in the preoperative with that given in the postoperative setting. Although a difference in survival was not observed, these preoperative trials established that neoadjuvant chemotherapy is equivalent to the postoperative therapy in terms of efficacy.9

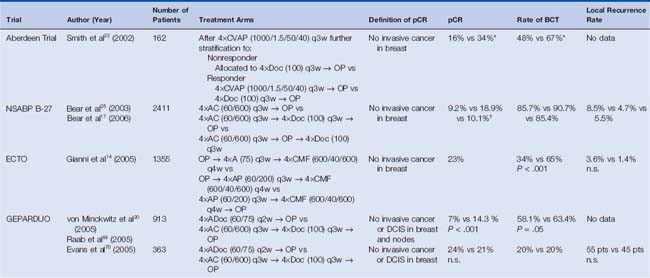

Early trials included CMF-like and anthracycline-based regimens and more recent trials have also included taxanes. The Aberdeen trial was the first study incorporating a taxane.22 The 162 randomized patients received four cycles of an anthracycline-containing regimen (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisone, CVAP) and were then— depending on their response to therapy—further stratified to either four cycles of docetaxel (nonresponder) or to another four cycles of CVAP versus four cycles of docetaxel (responder). The addition of docetaxel to the treatment of the responders was associated with an improved pCR rate of 34% compared with 16% with CVAP. With a 65-month follow-up, an impressive survival benefit could be demonstrated in the Aberdeen study in women who received a taxane in addition to anthracycline-based regimen.23 The Aberdeen trial results suggested that the implementation of a non–cross-resistant agent might improve the outcome for patients regardless of response to the initial therapy. MD Anderson Cancer Center investigators performed a similar study that included 190 patients treated with three cycles of vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone (VACP). After surgery, women were assigned according to the pathologic tumor size. Patients with a residual tumor smaller than 1 cm3 received five additional cycles of the preoperative regimen, whereas patients with a residual tumor larger than 1 cm3 were stratified to a non–crossresistant therapy consisting of vinblastine, methotrexate with calcium leucovorin rescue, and fluorouracil (VbMF).24 The pCR rate after VACP was relatively small (12.2%). The difference between the two postoperative treatment regimens in terms of relapse-free survival and overall survival did not reach statistical significance; however, the sample size was small. Given the small sample size in studies reported to date, it is too early to state whether responders or nonresponders have more benefit when crossing to a nonresistant regimen.9 These observations provided inspiration to a number of large prospective trials, such as the GEPARTRIO trial.

The largest neoadjuvant trial that incorporated a taxane was the NSABP B-27, and its results were concordant with the results of the Aberdeen trial with a larger number of patients and a different anthracycline-containing regimen (AC.)25 Different chemotherapy regimens have been administered in the neoadjuvant setting including sequential, concurrent, and both sequential and concurrent delivery of substances. The International Expert Panel reviewed the available data and recommended that, once a decision is made, all chemotherapy should be administered before surgery and that the preoperative regimen should include anthracyclines and taxanes26 (Table 17-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree