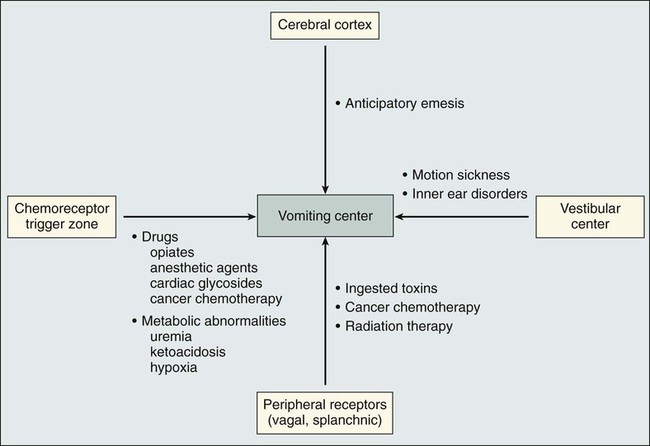

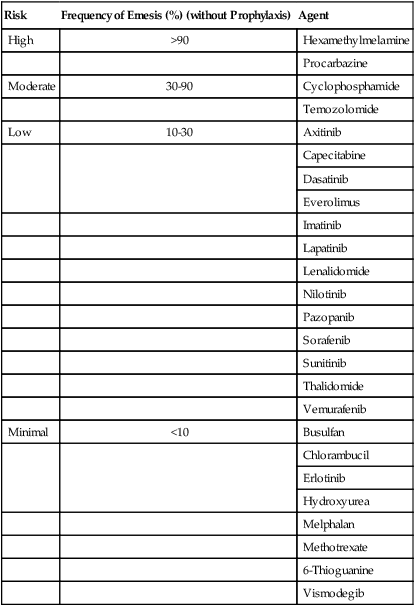

• Most common chemotherapy-associated toxicities • More frequent and severe with repetitive doses of chemotherapy • Significant impact on quality of life and can influence patient compliance with treatment • Acute nausea and vomiting often mediated by activation of serotonin type 3 receptors in the gastrointestinal tract • Mechanism of delayed nausea and vomiting (more than 24 hours after chemotherapy) unknown • Risk factors, including type of chemotherapy (drugs, doses, schedule), age, sex, and prior alcohol use should be assessed before treatment • Episodes of vomiting should be recorded (number, duration, and time to onset); severity of nausea can be graded with a visual analog scale • Optimal treatment provides complete control of acute nausea and vomiting in the majority of patients receiving chemotherapy; only 15% of patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy regimens have severe nausea and vomiting • Treatment of delayed nausea and vomiting has improved with the introduction of aprepitant and palonosetron; this complication can now be completely controlled in two thirds of patients Nausea and vomiting are common adverse effects associated with systemic chemotherapy and are among the adverse effects most feared by patients.1,2 Although these complications of treatment are usually self-limiting and are seldom life-threatening, the deleterious effects on nutritional status and quality of life can be substantial. Many recently introduced therapeutic antibodies and oral agents have less potential to produce nausea and vomiting. However, combination chemotherapy continues to be the cornerstone of treatment for many types of cancer, ensuring that antiemetic therapy will continue to be an integral aspect of supportive care. Antiemetic therapy has improved dramatically during the past 20 years. With optimum treatment, most patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy do not experience any nausea or vomiting during the 24 hours after treatment.3–11 However, delayed symptoms are more common and are often underestimated by treating physicians and nurses.12 Accurate assessment of delayed nausea and emesis is essential in providing maximal intervention with recently available agents. The pioneering work of Borison and Wang13 more than 50 years ago provided the basis for understanding the vomiting reflex. In studies using ablative techniques and electrical stimulation with microelectrodes (primarily in decerebrate cats), these investigators proposed the existence of two distinct sites in the brainstem believed to be critical for the control of emesis. The first of the sites, the so-called vomiting center, was thought to be located in the lateral reticular formation of the medulla. Electrical stimulation of this site triggered the vomiting reflex, whereas ablation prevented the vomiting induced by a variety of stimuli. The vomiting center was thought to be located adjacent to the other structures involved in the coordination of vomiting, including the respiratory, vasomotor, and salivary centers, and cranial nerves VIII and X. More recent studies have suggested that the “vomiting center” is actually not anatomically discrete but that the initiation of the vomiting reflex is controlled by a complex system of networks located in the brainstem, including the parvocellular reticular formation, the Bötzinger complex, and the nucleus tractus solitarius.14,15 The networks in this area coordinate complex patterns of motor activity such as the vomiting reflex and are more accurately described as “central pattern generators.” Although these concepts have been retained and are integral to the current understanding of the vomiting reflex, several other important components have also been recognized. Input from the gastrointestinal tract, predominantly through afferent vagal fibers, is critical in initiating the vomiting reflex after ingestion of noxious substances.16 Incoming vagal afferents connect with the vomiting center directly; an intact CTZ is not essential when vomiting is initiated by this mechanism. It is now known that in addition to ingested substances, some blood-borne substances, including chemotherapeutic agents, can trigger the vomiting reflex through activation of the vagal afferent mechanism. Two additional components of this complex system involve the vestibular apparatus and the higher brainstem and cortical structures. The vestibular system is involved primarily in initiating the vomiting reflex in persons with motion sickness. Input from higher cortical centers seems to be critical in a variety of conditions, including anticipatory emesis seen in patients who have previously experienced chemotherapy-induced emesis. The various components of the vomiting reflex are illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 42-1, along with the clinical situations in which they are operative. Given the complexity of this system, it is not surprising that different pharmacologic approaches are necessary to control vomiting of different etiologies. Improved understanding of the neurochemistry of the emetic reflex has been important in developing antiemetic agents with new mechanisms of action. The initial focus of such investigation was the area postrema, where receptors for a large number of neuroactive agents have been identified.19–19 Many of these neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine, histamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and substance P) are in themselves emetogenic agents. The development of pharmacologic agents that block specific sets of receptors (e.g., dopamine and neurokinin-1 [NK1]) has resulted in the identification of valuable antiemetic drugs, and it is likely that continued efforts in this area will yield additional valuable agents in the future. In addition to neurotransmitters located in the CTZ, type 3 serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine 3 [5-HT3]) receptors are present in large quantities on vagal and splanchnic afferents within the gastrointestinal tract.20 These peripheral receptors are pivotal in the initiation of the acute nausea and vomiting caused by cisplatin and other strongly emetogenic chemotherapeutic agents; inhibition of this pathway by specific 5-HT3 receptor antagonists results in highly effective antiemetic therapy.21 Acute nausea and vomiting after the administration of chemotherapy occur within 24 hours after the chemotherapy dose. The nausea and vomiting are the most severe during this phase, hence the emphasis on therapeutic intervention at this stage. With most chemotherapeutic agents, acute nausea and vomiting begin 1 to 2 hours after intravenous (IV) administration. This delay in onset argues against a direct effect at the CTZ, which would be expected to produce emesis within minutes of IV drug administration. A peripherally mediated vomiting reflex, probably serotonin release from small intestinal mucosa, offers a better explanation of the delayed onset of emesis.22 The onset of nausea and vomiting after the IV administration of cyclophosphamide is delayed even longer than with other agents, typically occurring 9 to 18 hours after administration of the drug.23 The mechanism of cyclophosphamide-induced nausea and vomiting is unclear; the difference in the time of onset suggests that the mechanism might differ from that of other agents. Delayed nausea and vomiting occur 24 or more hours after administration of chemotherapy. Although the severity is decreased in comparison with acute nausea and vomiting, the course can be more protracted, resulting in significant difficulties with hydration, nutrition, and performance status. Delayed emesis is most severe and frequent after administration of high-dose cisplatin; most patients treated with this drug experience some degree of delayed emesis, with onset most frequently occurring 24 to 72 hours after chemotherapy.24 In some patients, onset can occur as late as 4 to 5 days after treatment and can persist for several days. Patients who have poor control of acute nausea and vomiting are more likely to experience delayed nausea and vomiting as well; however, delayed emesis can occur among patients who have complete emetic control during the first 24 hours after administration of chemotherapy. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting often occur among patients who have experienced poor control of emesis during previous courses of chemotherapy.25 The onset can occur before or during administration of chemotherapy. Because this response is conditioned, certain associations with chemotherapy administration, such as the hospital environment or the oncologist’s office, might trigger the onset of emesis. Multiple clinical factors that are important in determining the incidence and severity of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting have been identified. These factors include the type of chemotherapy administered, certain patient characteristics, and the antiemetic regimen used (Box 42-1). A four-level classification of IV antineoplastic agents (high, moderate, low, and minimal) is widely accepted and is used to produce recommendations for antiemetic therapy.26,27 Table 42-1 summarizes the emetogenic potential of commonly used IV antineoplastic agents. Drugs in the high-risk category produce emesis in more than 90% of patients and require maximum antiemetic prophylaxis, whereas drugs with minimum risk produce emesis in fewer than 10% of patients and require no routine prophylaxis. The drugs that cause emesis most frequently also cause the most severe emesis. Emesis is most severe during the first 8 hours after onset, but with strongly emetogenic drugs, patients are often ill throughout the 24-hour period after administration. Table 42-1 Emetogenic Potential of Commonly Used Intravenous Antineoplastic Agents Adapted from Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, et al. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol 2010;21(Suppl. 5):v232–43. Oral agents are increasingly common in the treatment of cancer. Most of these agents have a lower risk of emesis than agents administered intravenously. However, antiemetic therapy can be problematic because of the chronic administration schedules of most oral agents; with prolonged administration, even low-level nausea can become a significant problem. The emetogenic risk of commonly used oral agents is summarized in Table 42-2. In general, the estimates of risk are based on the risk during an entire course of therapy, rather than a single dose. Because nausea or emesis can first occur several days of dosing, it is likely that this problem has been underreported for some of the oral agents. Table 42-2 Emetogenic Potential of Commonly Used Oral Antineoplastic Agents Adapted from Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, et al. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol 2010;21(Suppl. 5):v232–43.

Nausea and Vomiting

Introduction

Physiology of the Vomiting Reflex

Clinical Features of Chemotherapy-Induced Emesis

Clinical Syndromes

Acute Nausea and Vomiting

Delayed Nausea and Vomiting

Anticipatory Nausea and Vomiting

Prognostic Factors

Chemotherapeutic Agents

Risk

Frequency of Emesis (%) (without Prophylaxis)

Agent

High

>90

Carmustine

Cisplatin

Cyclophosphamide ≥1500 mg/m2

Dacarbazine

Mechlorethamine

Streptozocin

Moderate

30-90

Alemtuzumab

Arsenic trioxide

Azacitidine

Bendamustine

Carboplatin

Clofarabine

Cyclophosphamide <1500 mg/m2

Cytarabine ≥1 g/m2

Doxorubicin

Epirubicin

Eribulin

Idarubicin

Ifosfamide

Irinotecan

Melphalan ≥50 mg/m2

Methotrexate ≥250 mg/m2

Mitoxantrone

Oxaliplatin

Low

10-30

Bortezomib

Cabazitaxel

Cytarabine <1 g/m2

Cetuximab

Docetaxel

Doxorubicin (liposomal)

Etoposide

5-Fluorouracil

Gemcitabine

Yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan

Ixabepilone

Methotrexate <250 mg/m2

Mitomycin

Paclitaxel

Panitumumab

Pemetrexed

Temsirolimus

Topotecan

Tositumomab/iodine-131 tositumomab

Minimal

<10

Asparaginase

Bevacizumab

Bleomycin

Cladribine

Fludarabine

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin

Ofatumumab

Pentostatin

Rituximab

Trastuzumab

Vinblastine

Vincristine

Vinorelbine

Risk

Frequency of Emesis (%) (without Prophylaxis)

Agent

High

>90

Hexamethylmelamine

Procarbazine

Moderate

30-90

Cyclophosphamide

Temozolomide

Low

10-30

Axitinib

Capecitabine

Dasatinib

Everolimus

Imatinib

Lapatinib

Lenalidomide

Nilotinib

Pazopanib

Sorafenib

Sunitinib

Thalidomide

Vemurafenib

Minimal

<10

Busulfan

Chlorambucil

Erlotinib

Hydroxyurea

Melphalan

Methotrexate

6-Thioguanine

Vismodegib

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nausea and Vomiting