World Health Organization classification for myeloproliferative neoplasms 2008

Chronic myelogenous leukemia

Polycythemia vera

Essential thrombocythemia

Primary myelofibrosis

Chronic neutrophilic leukemia

Chronic eosinophilic leukemia, not otherwise specified

Hypereosinophilic syndrome

Mast cell disease

MPN, unclassifiable

Over the past two centuries our understanding of myeloproliferative neoplasms has evolved from their original clinical and hematopathological observations to an increasing appreciation of the molecular mechanisms underpinning the neoplastic process and their interplay with clinical phenotype and therapy. The disorders including chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), PV, and PMF were all identified as clinical and pathological entities in the nineteenth century. ET was delineated later by Epstein and Goedel in 1934, post-PV MF was described by Hirsch in 1935, and so during the first half of the twentieth century the inter-relationship between these disorders began to be defined. Dameshek however was the first author to formally articulate the idea of a common ‘myeloproliferative’ heritage in his landmark publication of 1951 stating: “It is possible that… ‘myeloproliferative disorders’ – are all… variable manifestations of proliferative activity of the bone marrow cells, perhaps due to a hitherto undiscovered stimulus” [3]. Dameshek thus importantly postulated not only the possibility of transition between these disorders, but more interestingly a common primary mechanism for all MPNs. Dameshek’s proposal of a common underlying pathology began to bear fruition during the 1980s with growing evidence that tyrosine kinase (TK) activity provided the molecular mechanism for CML which is not formally discussed further in this chapter.

An acquired point mutation in the JAK 2 (JAK2 V617F) gene occurs in most patients with PV and almost half of those with ET or PMF and less prevalent mutations have been described in exon 12 of JAK2 and the transmembrane domain of the thrombopoietin receptor cMPL as well as others [4]. The JAK2 V617F mutation disrupts the secondary structure of the pseudokinase domain and then enables constitutive, cytokine-independent activation of signal transduction pathways, enhancing cell proliferation. The functional consequences of the mutations effecting exon 9 of CALR are not yet clear and they are beginning to be integrated into diagnostics. This has revolutionized the investigation and diagnosis of these conditions and has been incorporated into standard diagnostic pathways in a rational manner [5]. There have only been four large clinical trials, ECLAP [6], PT1 [7] and the COMFORT studies [8, 9] in these conditions to date, these have enabled hematologists to refine evidence-based management further, while current clinical trials focus upon novel agents used alone and in combination [10]. Each of the three commonest entities will now be considered in turn.

Polycythemia Vera

Clinical Features and Epidemiology

PV or Vasquez disease is characterized by raised red cell mass (erythrocytosis) usually but not always in combination with thrombocytosis and/or neutrophilia; pruritus, gout and splenomegaly are classical clinical features. The median age at presentation of PV is 55–60 years. Clinical events include arterial and to a lesser extent venous thromboses often at atypical sites (e.g. abdominal venous thrombosis) or rarely bleeding. Over 10–15 years, myelofibrosis occurs in 10–15 % and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 5–10 % of patients with this disease and as demonstrated in the ECLAP study AML is more common in patients who are older (over 65 years), treated with drugs known to increase this risk such as alkylating agents, and smokers [11].

A packed cell volume (PCV or hematocrit) persistently greater than 0.52 in a male, or 0.48 in a female, should trigger investigation, however there is a wide differential diagnosis of potential causes of an erythrocytosis as summarised in Table 6.2. Assessment of patients suspected of an erythocytosis should include a thorough history and examination, full blood count/film, haematinics, renal/liver profile, urate, JAK2 V617F screen, urinalysis and chest X-ray (especially for smokers). In the absence of an obvious secondary cause and no detectable JAK2 V617F mutation, a red cell mass may be required to identify an absolute erythrocytosis (i.e. a truly raised red cell count). Additional tests include serum erythropoietin level (suppressed in PV), bone marrow biopsy, screening for mutations in exon 12 of JAK2, truncated erythropoietin receptor, proline dehydroxylase abnormalities, abdominal ultrasound, sleep studies and screening for a high-affinity haemoglobin. The diagnostic criteria for PV are shown in Table 6.3.

Table 6.2

Causes of an erythrocytosis

Causes of absolute erythrocytosis |

Primary (abnormality within RBCs) |

Congenital |

Truncated erythropoietin receptor |

Acquired |

Polycythemia vera |

Secondary (abnormality outside RBCs) |

Congenital |

Inherited high erythropoietin levels |

Abnormal hemoglobin with increased oxygen affinity |

Reduced 2,3-diphosphoglycerate |

Mutation in von Hippel–Lindau gene |

Mutations in proline dehydroxylase genes |

Acquired (increased erythropoietin) |

Conditions causing low oxygen levels – high altitude, chronic lung disease, some congenital heart diseases |

Renal disease – tumours (hypernephroma), cysts (usually benign), hydronephrosis, following kidney transplantation |

Liver disease – hepatoma, cirrhosis, hepatitis |

Tumours – bronchial cancer, fibroids in the uterus, cerebellar haemangiomata |

Endocrine abnormalities – Cushing’s syndrome, phaeochromocytoma |

Idiopathic (undefined primary or secondary) |

May resolve or pathology may be masked initially |

Causes of apparent erythrocytosis |

Normal variant |

Early absolute erythrocytosis |

Obesity, fluid loss, diuretics, smoking, hypertension, alcohol, renal disease, psychological stress |

Table 6.3

Diagnostic criteria for the MPNs

Worldwide estimates of the incidence of PV vary greatly, with the incidence thought to be between 2 and 2.8 per 100,000, with a slightly higher male preponderance.

One of the largest studies of a cohort of PV patients, the European Collaboration on Low-dose Aspirin in PV (ECLAP) over a median period of 2.8 years, revealed that the mortality of patients with PV was 2.1 times higher that of the standard population, with cardiovascular complications playing a significant role [11]. A predominance of arterial events and non-hemorrhagic cerebral vascular events was noted. Abdominal venous thrombosis such as Budd-Chiari syndrome, and obstruction of the portal, mesenteric and splenic systems have often been seen in patients with PV. A previous history of thrombotic events and a rising age are felt to independently increase the risk of further thrombotic events in this sub-group of individuals. These results were corroborated by the results of the ECLAP study whereby those over the age of 65 years and with a prior history of a thrombotic event were noted to have the highest risk of cardiac complications.

Leucocytosis appears to be another independent risk factor, whereby individuals with a WCC >15 × 109 are at a higher risk of vascular events. This has been attributed to endothelial and platelet activation, leading to acceleration of arteriosclerosis [12]. Hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking and diabetes are independently associated with atherosclerosis, and in the context of their presence in patients with PV should be managed aggressively [13].

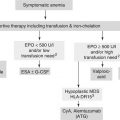

Management and Prognosis of PV

The risk of vascular events in treated PV patients remains raised at approximately 1.6 times normal despite optimal modern management [11]. Transformation to either Myelofibrosis or AML following PV are treated as per myelofibrosis (see below) or usually supportively, as the outlook is extremely poor; stem cell transplantation is an option in a minority of suitably fit patients who transform. Reversible factors for cardiovascular disease should be managed aggressively and low-dose aspirin considered unless contraindicated, e.g. active or previous peptic ulcer disease, prominent bleeding symptoms and presence of acquired von Willebrand’s disease. The European Collaboration on Low-dose Aspirin in PV (ECLAP) study found low-dose aspirin was effective in reducing the number of thrombotic events as well as micro vascular symptoms such as erythromelagia which is associated with the spontaneous aggregation of platelets. Treatment includes repeated venesection or cytoreductive therapy to keep the PCV below 0.45 in males, and females, and in some patients the platelets less than 400 × 109/l. The target for venesection was recently confirmed in a prospective study [14].

Cytoreduction is clearly indicated if patients are intolerant of venesection or indeed if they develop thrombocytosis, symptomatic splenomegaly or a thrombosis [13]. Hydroxyurea (or hydroxycarbamide, HC) is the cytoreductive drug of first choice. Concern that it might increase the risk of leukemia is not proven but the use of phosphorus-32 (P32) or busulfan is restricted because of their well-defined leukemogenic potential. Interferon alpha (IFN) is a non-leukemogenic alternative and recent data suggest that pegylated IFN may reduce JAK2 V617F levels, potentially eradicating the abnormal clone. Intermittent busulphan or P32 can be used in the very frail, in whom regular out-patient visits are not practical or compliance is an issue, bearing in mind their leukemogenic potential. Investigational agents include JAK inhibitors and Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors which are currently being assessed in clinical trial. A current trial is directly comparing IFN and HC.

Therapuetic Options and Considerations for the Elderly Patient with PV

Therapeutic options in managing elderly patients with PV is dependent on the use of the appropriate agent, taking into consideration the phase of the disease, age of the patient as well as their ability to tolerate or comply with therapy. Treatment affects overall survival, with those that remain untreated having an average survival of 18 months, with thrombotic events being the predominant cause of morbidity and mortality. Those who are treated have on average a median survival of 10–15 years.

The aim of cytoreduction in PV is to minimise the overall risk of thrombotic events, control disease-related symptoms and reduce the risk of disease progression. The needs of older patients are often different from those of younger patients. In particular, the impact of reduced physiological reserve as well as multiple-morbidities needs to be taken into account. Elderly patients commonly have multiple pathologies leading to polypharmacy, in addition to altered pharmacokinetics as well as pharmacodynamics. In this sub-group of patients, optimisation of their existing therapies, looking into their ability to tolerate various available therapies, and optimisation of their ability with compliance of therapy needs careful forethought. In such scenarios, a dedicated review by the elderly care team with close liaison with the treating hematologist can play a vital role in optimisation of drug use amongst this high-risk group.

Essential Thrombocythemia

Clinical Features and Epidemiology of ET

ET is characterized by a persistent thrombocytosis and recent WHO criteria suggest patients with platelets persistently over 450 × 109/l merit investigation (see also Table 6.3) [2]. Clinical features are very similar to PV. Microvascular events are said to predominate here including erythromelalgia (asymmetric erythema, congestion and burning pain in the hands and feet) which may progress to ischaemia and gangrene, migrainous-like headaches and transient ischaemic attacks. The long-term risk of myelofibrosis and leukemia is perhaps lower than that with PV. ET is perhaps one of the most common myeloproliferative neoplasms and is thought to have an annual incidence of between 1 and 2.5 per 100,000 individuals according to the WHO. It is often identified as an incidental finding. It is predominantly diagnosed in patients between 50 and 60 years, with what appears to be an even distribution between both male and females though in younger patients there is a female preponderance [15].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree