Fig. 6.1

Expected emotions and reactions for the SCCHN patient

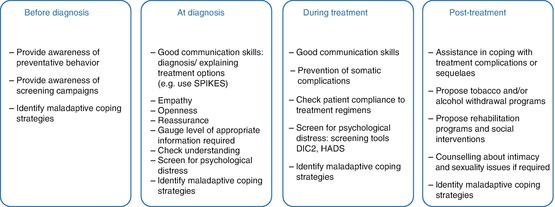

Fig. 6.2

Recommended actions for the healthcare professional. DIC2 Distress Inventory for Cancer version 2, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, SCCHN squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, QoL quality of life (From Reich et al. [21], reproduced with permission)

Do MDT Meetings Impact on Diagnosis, Treatment Decision, and Outcome?

It seems self-evident that the variety of specialist team members with their combined knowledge and expertise will improve decision-making and therefore ultimately patient management and outcome. Although that is very likely so, evidence for that has not been easy to demonstrate because, as outlined above, over time cancer care is changing, there is improvement in staging and diagnosis, and more effective treatments become available. These aspects are, of course, confounding factors in retrospective studies where one looked at whether the introduction of MDT meetings had any impact on outcome (so-called “before and after” studies). Prades et al. undertook a literature search in the Medline database for peer-reviewed articles (partly retrospective, partly prospective) published between November 2005 and June 2012 that examined multidisciplinary clinical practice and organization in cancer care [22]. MDTs resulted in better clinical and process outcomes for cancer patients with evidence of improved survival among colorectal, head and neck, breast, esophageal, and lung cancer patients in this study period. However, unfortunately the two studies in that survey that concerned HNC were both retrospective [23, 24].

Friedland et al. [23] analyzed the outcomes of 726 cases of primary HNC patients managed between 1996 and 2008, including 395 patients managed in a multidisciplinary clinic or team setting and 331 managed outside of an MDT by individual disciplines. Data were collected from the Hospital Based Cancer Registry (HBCR) and a database within the Head and Neck Cancer Clinic of the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, Australia. The MDT patients were younger by about 2 years of age on average (p = 0.046), which is a potential source of bias. On the other hand, patients seen in the multidisciplinary clinic were more likely to have advanced disease (p < 0.001). The authors reported a better outcome for the patients in the MDT group (for all patients with stage I–IV a hazard ratio [HR] of 0.79, p = 0.024), but this was mainly due to a different outcome in the stage IV patients (HR = 0.69, p = 0.004). There was no difference observed in stage I–III, although the numbers in each of these stages were too small to provide statistical power. Over time there was an increasing incidence in the use of CCRT (2.1 % in 1996 and 42.5 % in 2008; test for trend p < 0.001) and at the same time a decline in the use of radiotherapy alone (27.1 % in 1996 and 15 % in 2008; test for trend p < 0.001). Patients in the multidisciplinary clinic were significantly less likely to receive radiotherapy alone for positive nodes or surgery alone for their cancer and positive nodes. The MDT group used significantly more CCRT (p = 0.004) and the non-MDT group significantly more radiotherapy alone (p = 0.002).

Wang et al. [24] reported on a study performed in Taiwan, where the incidence of oral cavity cancer is very high (about 60 % of all HNC). They used for their study the National Health Database (2004–2008) and applied matching based on propensity of receiving MDT care. After the propensity score matching, 3099 MDT care participants and 6198 non-MDT care participants were included in the study. The relative risk of death was lower with MDT care than for those without MDT care (HR = 0.84; 95 % CI 0.78–0.90, p < 0.001). The effect of MDT care was stronger for older patients.

In two prospective studies, treatment plan changed in about one third of cases after MDT. The first study was performed at the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery of the University of North Carolina Hospital in North Carolina, in the USA, and concerned 120 new patients (84 with malignant, 36 with benign tumors) whose clinical findings were presented for review at the MDT meeting between December 2009 and February 2010 [25]. Approximately 27 % (32/120) had some change in either tumor diagnosis or treatment plan due to the input from the multidisciplinary tumor board. Three (9 %) of these 32 patients had changes in both diagnosis and treatment, 19/32 (59 %) had a change in their treatment plan without a change in diagnosis, and 10/32 (31 %) had a change in diagnosis without a change in treatment. Approximately 7 % of patients required further diagnostic workup before definitive treatment planning. The second study was executed at the Sydney Head and Neck Cancer Institute at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, a tertiary care hospital in Central Sydney, Australia [26]. One hundred seventy-two patients with head and neck tumors (160 malignant, 12 benign) were discussed in 39 meetings over the period from December 2011 until October 2012. The proposed management plans were documented before the MDT meeting, and the MDT meeting recommendations and potential changes to the initial plan were recorded after the meeting. The changes were categorized as major or minor: changes were considered major when they concerned a change in treatment modality, while changes were considered minor when they comprised alterations in the extent of a chosen modality, the addition of diagnostic tools or research decisions. Compliance with MDT recommendation was evaluated after completion of treatment. Of the 172 patients, 52 (30 %) had management changes, 35 (67 %) of which were considered major and 12 (33 %) considered minor. Interestingly, a significant association was found between the frequency of changes in treatment plan and the referring consultant’s specialty (more likely in case referrals by medical oncologists or radiation oncologists than by surgical oncologists), the initial treatment plan (when the treatment plan did not include surgery) and the histological tumor source (least likely in case of mucosal tumors). The recommendations of the MDT meeting were followed in 132 (84 %) of the 158 patients on which data were available. Of the 26 cases where the treatment plan was not followed, a more aggressive plan was chosen by the treating physician in 50 %, in 40 % it was less aggressive, and in 10 % the modality changed (surgery replacing RT or vice versa). Reasons for this noncompliance were variable: unexpected findings in the surgical specimen, patient preference, and/or change in functional status between the MDT meeting and the actual start of the treatment. Given the complex and mutilating nature of SCCHN treatments and the advanced age and frequent comorbidities in HNC patients, the authors considered the compliance to the recommendations in this study high (84 % overall, 70 % for patients with changes). On the other hand, still worrisome is the fact than in 15 % of cases the treatment agreed upon was not carried out.

A disadvantage of MDT meetings that sometimes has been mentioned by some authors is that this might potentially lead to delay in starting treatment [26]. However, this will be particularly the case when the interval between MDT meetings are long. In most institutions, MDT meetings take place at weekly intervals. However, the point is well taken. It is very well known that treatment delay is associated with a less favorable outcome [27, 28]. A recently performed systematic review with meta-analysis of ten studies showed that the estimated relative risk (RR) of mortality related to any diagnostic delay (either patient or professional delay) was 1.34 (95 % CI, 1.12–1.61) [29]. Therefore, studies that investigate how to reduce time intervals are of interest. One such initiative was taken by the Danish group and showed that a fast-track program through logistic changes, employment of a full-time case manager, strengthening the multidisciplinary tumor board, and giving higher priority to HNC patients (by introducing a hotline for referrals, having prebooked slots in the outpatient clinic, having faster pathology reports and imaging procedures), the overall time from first suspicion of cancer until treatment start could be reduced from 57 calendar days to 29 calendar days [30].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree