Local recurrence from rectal cancer is a complex problem that should be managed by a multidisciplinary team. Pelvic reirradiation and intraoperative radiation should be considered in the management of these patients. Long-term survival can be achieved in patients who undergo radical surgery with negative margins of resections. The morbidity of these procedures is high and at times may compromise quality of life. Palliative surgical procedures can be considered; however, in some cases, palliative resections may not be better than nonsurgical palliation.

Despite advances in surgical techniques and the use of chemoradiation, local recurrence is still a significant problem in the management of cancer of the rectum. Locally recurrent rectal cancer (LRRC) can be debilitating and potentially lead to a poor quality of life (QOL). In the last decade, the incidence of local recurrence after curative resection for rectal cancer has been reported to be between 5% and 17%. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 50% of the patients with LRRC will have metastatic disease, but between 30% and 50% of patients will die with local disease alone. Prognosis among patients with LRRC can be poor because the majority of these patients will not be candidates for salvage surgical resection. The median survival in untreated patients has been reported to be about 8 months. Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy increases survival to about 11 to 15 months. With aggressive multimodality therapy, for LRRC, the overall 5-year survival rate is 25% to 54%, with higher survival rates for those patients resected with negative margins. In this article, the multidisciplinary approach to the management of patients with recurrent rectal cancer is discussed.

Clinical presentation

The vast majority of local recurrences occur within the first 2 to 3 years after curative surgery. Nevertheless, local recurrence can occur after longer intervals. In fact, in patients treated with local excision with or without chemoradiation, local recurrences have been reported at intervals of more than 6 years after primary treatment. The majority of patients who develop local recurrence will be symptomatic. The most common symptoms include new onset of pelvic or perineal pain, change in bowel habits, rectal bleeding, and urinary symptoms. In patients who have undergone an abdominoperineal resection, a nonhealing wound could be a sign of locally recurrent disease.

Evaluation and imaging

For the group of patients who may be candidates for potential surgical resection, careful staging and treatment planning should be performed by a multidisciplinary team. This team includes the surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, urologist, plastic and reconstructive surgeon, radiologist, pathologist, enterostomal nurses, social workers, and at times a psychiatrist. A thorough evaluation should be performed to select patients in whom a complete surgical resection can be achieved with negative margins, because these patients will be the ones most likely to benefit. Surgical salvage procedures for LRRC include en bloc resection of adjacent organs or structures, such as total pelvic exenterations (TPE) and abdominosacral resection (AR), which are highly morbid, and thus could lead to worse quality of life for patients than symptomatic management.

A careful history and physical examination should be performed. In patients presenting with pain, the quality and characteristics of the pain are important in determining the potential for resectability. Patients with LRRC presenting with pain radiating to the back of the leg will most likely have involvement of the sciatic nerve and most likely will not be amenable to resection as opposed to patients presenting with just pelvic discomfort. It is important to elicit symptoms and signs regarding adjacent structures, such as pneumaturia, fecaluria, vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain with cramps, recurrent fever or chills, and weight loss, among others. Once a careful history has been taken, a physical examination, including rectal and vaginal examination and proctoscopy (in those patients who have had a sphincter-saving procedure), should be performed. This examination will allow evaluation for whether or not the recurrence is fixed, and may give the clinician an idea of the extent of the recurrence, such as involvement of the bladder or prostate, vagina, perineum, and on occasion metastatic disease to the groins. An effort should be made to obtain prior medical records, including operative reports, radiation therapy treatment plans and dosage given, as well as documentation regarding chemotherapy administered. As discussed later, patients with LRRC are candidates for reirradiation, and thus, prior radiotherapy records are important in planning re-treatment. At times it is difficult to evaluate patients in the office or clinic setting, and thus, an examination under anesthesia is necessary. In the authors’ practice, every effort is made to tissue document a local recurrence before embarking in the multimodality treatment of a local recurrence.

Evaluation of patients with locally recurrent rectal cancer should include

History and physical examination (obtain previous medical records, including operative reports, radiation schedule and portals, and chemotherapy schedules)

Proctoscopy

Colonoscopy

Imaging

Computerized axial tomography (CAT)

MRI

Positron emission tomography (PET)

Positron emission tomography and CAT scan (PET/CT).

Evaluation and imaging

For the group of patients who may be candidates for potential surgical resection, careful staging and treatment planning should be performed by a multidisciplinary team. This team includes the surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, urologist, plastic and reconstructive surgeon, radiologist, pathologist, enterostomal nurses, social workers, and at times a psychiatrist. A thorough evaluation should be performed to select patients in whom a complete surgical resection can be achieved with negative margins, because these patients will be the ones most likely to benefit. Surgical salvage procedures for LRRC include en bloc resection of adjacent organs or structures, such as total pelvic exenterations (TPE) and abdominosacral resection (AR), which are highly morbid, and thus could lead to worse quality of life for patients than symptomatic management.

A careful history and physical examination should be performed. In patients presenting with pain, the quality and characteristics of the pain are important in determining the potential for resectability. Patients with LRRC presenting with pain radiating to the back of the leg will most likely have involvement of the sciatic nerve and most likely will not be amenable to resection as opposed to patients presenting with just pelvic discomfort. It is important to elicit symptoms and signs regarding adjacent structures, such as pneumaturia, fecaluria, vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain with cramps, recurrent fever or chills, and weight loss, among others. Once a careful history has been taken, a physical examination, including rectal and vaginal examination and proctoscopy (in those patients who have had a sphincter-saving procedure), should be performed. This examination will allow evaluation for whether or not the recurrence is fixed, and may give the clinician an idea of the extent of the recurrence, such as involvement of the bladder or prostate, vagina, perineum, and on occasion metastatic disease to the groins. An effort should be made to obtain prior medical records, including operative reports, radiation therapy treatment plans and dosage given, as well as documentation regarding chemotherapy administered. As discussed later, patients with LRRC are candidates for reirradiation, and thus, prior radiotherapy records are important in planning re-treatment. At times it is difficult to evaluate patients in the office or clinic setting, and thus, an examination under anesthesia is necessary. In the authors’ practice, every effort is made to tissue document a local recurrence before embarking in the multimodality treatment of a local recurrence.

Evaluation of patients with locally recurrent rectal cancer should include

History and physical examination (obtain previous medical records, including operative reports, radiation schedule and portals, and chemotherapy schedules)

Proctoscopy

Colonoscopy

Imaging

Computerized axial tomography (CAT)

MRI

Positron emission tomography (PET)

Positron emission tomography and CAT scan (PET/CT).

Imaging

To adequately stage patients with LRRC, once the initial evaluation is completed, imaging studies are performed. Although some investigators have advocated endorectal ultrasound (EUS) in patients with LRRC after local excision, the authors have not been able to demonstrate its utility in routine practice. EUS can be useful to perform needle-guided biopsy of a pelvic recurrence. CAT and MRI scans should be used to evaluate patients. The authors usually start evaluating patients with a CAT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. The advantage of doing this is that not only will local disease information be provided but distant disease can be identified. A pelvic MRI provides improved ability to distinguish posttreatment changes from viable tumor in comparison to CT imaging and provides excellent detail of surrounding pelvic structures, including sacral nerve roots, major pelvic vasculature, and bone, all of which are the parameters that need to be evaluated to determine resectability. It is important to note that with both of these modalities, the extent of involvement by the LRRC may be underestimated. Although not routinely part of the initial surgical staging, positron emission tomography fused with CAT scan (PET/CT) is employed in those cases where equivocal radiographic evidence of both local and distant disease is present. PET/CT has been reported to change the management in up to 14% of patients with LRRC.

Classification of the recurrence

Several classifications have been proposed for LRRC. The purpose of these classifications has been to define the structures that the LRRC involves, assess resectability, plan the extent of resection, and compare outcomes. The Mayo Clinic classification relies on the degree of fixation of the recurrence, and encompasses the earliest type of recurrences with no fixation to advanced recurrence with 3 or more points of fixation. Wanebo and colleagues proposed a classification based on modified criteria from the TNM staging system. In this classification, recurrences are described as local/minimal (within the bowel wall) to extensive invasion of the pelvis, including bony structures and sidewall. Yamada and colleagues classified the recurrences as localized, sacral invasive, and lateral invasive types and correlated survival with each type. None of the subjects with a lateral invasive recurrence survived 5 years. The Memorial Sloan Kettering classification is based on the anatomic location of the recurrence.

In the authors’ experience, the classification of recurrences based on anatomic location is clinically most useful. In general, anastomotic (after low anterior resections and transanal excisions), inferior or perineal recurrences, and central recurrences (those involving the rectum or urogenital organs) are the most amenable to surgical salvage. Posterior recurrences are also amenable to surgical salvage when sacral involvement remains below the second sacral vertebrae (S2). Lateral recurrences are the most difficult to address because involvement of the lateral bony pelvic structures, the major blood vessels, and other lateral structures may preclude a resection with negative margins.

Surgical planning

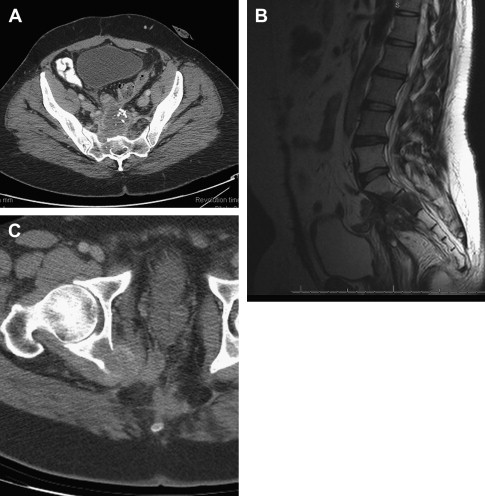

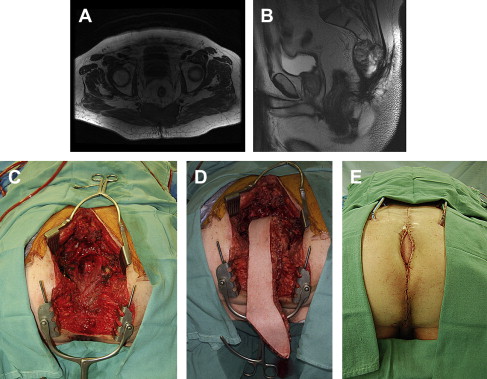

Once patients have been evaluated and the images reviewed, a thorough and frank discussion between the surgeon and patients regarding the options for treatment and the expected treatment outcomes is essential. In addition, presentation at a tumor board or a multidisciplinary conference to discuss the options of treatment is preferred. It must be understood that whenever surgery is being considered, imaging is only one part of the decision making process. Many factors need to be considered in the decision-making process, including the general status of patients, the physical findings, the available treatment options, the biology or aggressiveness of the disease, and the patients’ opinion. The following list demonstrates nonresectability criteria for locally recurrent rectal cancer. Fig. 1 illustrates 2 examples of unresectable recurrences; whereas, Fig. 2 shows a posterior recurrence and its reconstruction after an abdominosacral resection.

Preoperative criteria for nonresectability of locally recurrent rectal cancer

Anatomic

Involvement

Above S2 or sacral ala

Acetabulum

Common and external iliac arteries

Sciatic nerve or sciatic notch

Bilateral hydronephrosis (relative)

Biologic

Metastatic disease not amenable to resection

Para-aortic lymph node involvement

Patient

Poor performance status

Unacceptable surgical risks because of comorbidities

Technical

Inability to obtain a negative margin of resection.

If patients are considered to be potentially resectable with negative margins, both the surgeon and patients must understand that imaging is not perfect, and may underestimate the level of invasiveness or adherence by the recurrence. The surgeon must be prepared to remove the tumor and adjacent structures or organs adhered to the tumor. Surgical options for LRRC include local resection of the recurrence, bowel resection with primary anastomosis, abdominoperineal resection, pelvic exenteration, and abdominosacral resection.

In general, surgical resection of LRRC involves a multidisciplinary surgical team. In addition to the primary surgeon, the surgical team may include urologists, gynecologists, plastic and reconstructive surgeons, neurosurgeons, and radiation oncologists. Careful multidisciplinary planning will provide the most satisfactory results. Unfortunately, there are times where in order to intraoperatively assess resectability, the surgeon has to commit to performing the resection without knowing whether or not negative margins will be obtained. The authors’ call this the point of no return, and it is not an ideal situation because either microscopic or gross tumor will be left behind. If the procedure can be done with acceptable morbidity, it may indeed be a better situation than the potential complications resulting from trying to put back together structures that have been already severed or violated with the attendant complications and poor quality of life related to those potential complications or tumor-related issues.

Multimodality Therapy for Locally Recurrent Rectal Cancer

Surgery is the mainstay in the management of patients with LRRC. Chances of surgical salvage appear to improve according to the radicality of the primary procedure. In a series from The Netherlands, Dresen and colleagues reported that subjects who had undergone an anterior resection at the time of their primary tumor diagnosis had a 20% higher chance undergoing radical surgery for their LRRC than those subjects who had undergone an abdominoperineal resection at the time of their primary tumor surgery.

The 5-year survival after surgical salvage for LRRC has been reported to range between 18% and 58%. Morbidity has been reported to be between 21% and 82%. Wound complications have been a major source of morbidity in these patients. The incidence of major wound problems has decreased with the use of myocutaneous flaps. Perioperative mortality has been reported to be up to 8%. With advances in critical care, a multidisciplinary team approach, and specialized centers doing these procedures, mortality has decreased.

The majority of patients with local recurrence will have been treated with chemoradiation in addition to their primary tumor surgery. In those patients who have not been treated with chemoradiation, the latter needs to be considered before surgical salvage. To maximize the effects of chemoradiation, the authors usually wait 6 to 8 weeks before surgery. Valentini and colleagues reported 29% clinical downstaging after reirradiation and an 8.5% complete pathologic response in resected specimens. In that series, the overall response rate (complete response [CR] + partial response [PR]) after chemoradiation for locally recurrent rectal cancer was 44.1%. Das and colleagues reported a 3-year overall survival rate of 66% in 18 of 50 subjects who were re-treated with chemoradiation and underwent surgical resection compared with those who did not.

Patients who have been previously treated with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemoradiation can be re-treated safely with acceptable acute and late toxicity. The authors’ have reported their experience in re-treatment in 50 subjects with recurrent rectal cancer. Nearly all subjects received 150 cGy fractions twice a day for a total dose of 39 Gy and 48 of the 50 subjects received concurrent 5-fluorouracil–based chemotherapy. Two subjects developed grade 3 acute toxicity and 13 subjects (26%) developed grade 3 and 4 late toxicity. The most common acute toxicity was nausea and vomiting; whereas, the most common late toxicity was small bowel obstruction. Some subjects developed urinary complications, such as ureteral anastomotic stricture and leak, and vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas.

The goal of surgery is to remove the recurrent tumor with a negative margin. In LRRC, the incidence of R1 and R2 resections after surgical salvage has been reported to be between 40% and 58%. In the Mayo Clinic series, Hanhloser and colleagues reported on 304 subjects who underwent surgery for LRRC. Of these 304 resections, only 9% were considered extended resections (pelvic exenterations and abdominosacral resections). There were 138 subjects (45%) resected with negative margins. A statistically significant difference was reported in 5-year survival for subjects who underwent R0 resections versus those with R1 and R2 resections of 37% versus 16%, respectively. The investigators concluded that surgical margins were the most significant influence for long-term survival after salvage surgery for LRRC.

In 85 consecutive salvage resections for locally recurrent rectal cancer at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, R0 was achieved in 76% and the 5-year disease-specific survival, overall survival, and pelvic control rates were 46%, 36%, and 51%, respectively. On multivariate regression, negative predictors of overall survival included an elevated carcinoembryonic antigen level and R1 resection. Additional evaluation of biologic markers, including expression of p53, bcl-2, and ki-67, did not demonstrate associations with survival outcome.

Boyle and colleagues reported on 64 subjects who underwent surgery for LRRC. Seven of 64 subjects (11%) were found to be unresectable despite preoperative workup and imaging. Of the 57 subjects who underwent resection, 24 (42%) had R0 resection, 25 (44%) had R1 resection, and 8 (14%) had R2 resection. The morbidity in this study was 44% and the mortality was 1.6%. A total of 49% of the subjects re-recurred locally. Of these, 50% had had a R0 resection; whereas, 56% of those with re-recurrence had a R1 resection. The median survival for the 63 subjects discharged from the hospital was 33.6 months. The investigators reported that the median survival in subjects with R0 resection was statistically better than those with R1 resection.

Wanebo and colleagues reported on 53 subjects who underwent abdominosacral resections with curative intent for LRRC. In this study, only 8 subjects had positive margins of resection. The 5-year survival was 31% with a 5-year disease-free survival of 23%. The postoperative death rate was 8%, and the morbidity included 20% prolonged intubation, 34% sepsis, and 38% posterior wound or flap separation. The mean blood loss was greater than 8 L, and the total surgical time was approximately 20 hours. The investigators concluded that in well-selected patients, abdominosacral resection can be performed with acceptable morbidity and mortality.

Akasu and colleagues reported on 40 of 44 subjects who underwent abdominosacral resections with curative intent for LRRC, not involving S1 or the bony lateral pelvic sidewall, over a 17-year period. A total of 37 subjects had macroscopic curative resections, including 4 subjects who had metastatic disease resected. Contrary to Wanebo and colleagues, the procedure was performed as a 1-stage procedure and no myocutaneous flaps were used. R0 resection was obtained in 60% of the subjects. The mean operating room time was 7521 minutes and the median estimated blood loss was 3208 mL. The morbidity was 71%, including 10 subjects who required re-operation. The 5-year overall survival was reported to be 34%, with a 24% disease-free survival. Subjects with R2 resections did not survive more than 28 months after the operation. These investigators also reported that subjects with buttock pain had a worse outcome than those subjects with no pain or perineal pain. Subjects presenting with thigh or leg pain did worse than those with buttock pain. In this series, 25 of 37 (68%) subjects who underwent macroscopic curative resection recurred. Fifty-six percent recurred with local and distant disease. None of the re-recurrences were amenable to surgical salvage.

Sagar and colleagues reported on 40 subjects treated with a 2-stage abdominosacral resection for LRRC with curative intent. In 50% of the subjects, a R0 resection was achieved. The morbidity in this study was 60%, with a 30-day mortality of 2.5%. The mean disease-free interval for subjects with R0 resection was 55.6 months compared with 32.2 months for those with R1 resection. This difference was statistically significant.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree