Multidimensional Patient Assessment

Cameron J. Muir

Mary Wheeler

Jennifer Carlson

Nancy W. Littlefield

Introduction/Background

From the earliest times in medicine, there has been a significant emphasis on the relief of suffering. As Hippocrates said: “I will use treatment to help the sick” … and “to help, or at least to do no harm” (1). From the time of Hippocrates (approximately 500 bc) through the 19th century, the focus of health care has been on the relief of suffering associated with injury and disease. However, during the last half of the 19th century, the 20th century, and into the 21st century, health care has been largely focused on disease and has inadequately addressed care for the person. As a result, the disease has been treated, although the suffering that the patient is experiencing is often left unaddressed. It has only been during the past 25 years, that there has been a resurgence of the ethic of palliative care. This resurgence is most likely due to recognition of the limits of the current curative model of care: although we have become more proficient at staving off death, it will still occur 100% of the time (2). It is through a skilled multidimensional patient assessment (MDPA) that the various elements of suffering can be identified and addressed from diagnosis of a cancer, through treatment and into remission, or at disease progression, and on until death.

In this chapter, we will review the components of a multidimensional patient screening and assessment, which is often also referred to by the patient/family as “holistic or whole person” care. Particular emphasis will be placed on the role of an interdisciplinary team (IDT), and a distinction will be made between the traditional “medical model” and the interdisciplinary “biopsychosocial-spiritual model” of care, which is so well modeled in the field of hospice and palliative care. The different components of the MDPA will then be described with particular emphasis on knowing how and when to integrate other disciplines’ skills and assistance.

Interdisciplinary Assessment

There is a growing appreciation that a patients’ experience of their advanced illness is complex: from physical symptoms, to coping, finance, caregiver burden, social/family changes, and spirited concerns. And furthermore, that no one person—regardless of their professional discipline—will be able to manage all of these issues (3, 4, 5). In fact, attempts to do so may result in either harm to the health care provider through exhaustive efforts to deal with everything “myself” leading to stress and burnout (6, 7); or harm to the patient and family, because the health care provider either completely misses an issue due to lack of skill in that area, or by trying to do something that they are not adequately trained to do.

Each health care discipline has expertise and skills in providing care to the patient and family and in identifying their specific needs, and clarifying goals of treatment within a holistic framework. One might ask: “What discipline is most appropriate for performing an initial assessment?” Although there is little data to support an answer to this question, there is some anecdotal evidence from evaluation of the systems currently in place and what seems to work. There are two predominant models of care provided in health care: the traditional “medical” model, and the interdisciplinary/palliative care model. There are significant differences between the two models of care (8, 9).

The traditional medical model is the predominant model of health care and can be characterized as disease focused with the physician as the leader. Physicians run most ambulatory clinics that see patients with “problem lists” and “chief complaints”; a history is taken, and then a physical examination is performed. Based upon clinical findings, patients undergo diagnostic testing in an attempt to reveal a diagnosis for which some form of therapy is instituted to cure or at least improve the disease. This model often fails to take two critical elements into account: the nonphysical needs of the patient and family, and the fact that the vast majority of medical diseases in the 21st century are chronic, often progressive diseases that ultimately cannot be cured, only palliated. In the medical model, the primary mode of communication between health care providers is often the written chart note, with the involvement of other medical specialists, as well as other professional disciplines; this system is often haphazard and uncoordinated.

The interdisciplinary/palliative care model is team driven with the focus of care being the patient and family, rather than the disease (10, 11). Table 46.1 provides an overview of the discipline-specific components of a typical interdisciplinary assessment. Interdisciplinary care recognizes that the discipline that often spends the greatest amount of time with a patient and family is usually the nurse, and the nurse is also equipped with the broadest assessment skills. The nursing assessment in palliative care, whether performed in a unit, or in an ambulatory or community setting, is of paramount importance.

The nurse coordinates the plan of care for the patient and family as well as the IDT, which can include physicians, social workers, and pastoral caregivers among others (12). The nurse should have good physical assessment skills, a strong knowledge of current innovations in pain and symptom management, as well as astute psychological and spiritual

evaluation strategies to ensure the plan of care is congruent with the goals of the patient and family. The nurse is often in a position to develop the strongest therapeutic relationship with the patient and family.

evaluation strategies to ensure the plan of care is congruent with the goals of the patient and family. The nurse is often in a position to develop the strongest therapeutic relationship with the patient and family.

Table 46.1 Components of the Interdisciplinary Team Assessment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The nurse works with the patient and family using skilled compassion and concern; empowering the patient to exercise control in decision making where possible, which can only enhance the patient’s sense of control. The nurse continually reassesses the patient and family’s goals, treatment preferences, coping abilities, and support needs. The nurse is the conduit for information, critical assessments, and evaluation of the patient and family goals within the IDT. The physician can provide expertise about the disease, treatment options, risks and benefits, likely outcomes, and symptom management interventions. In addition, they can help to anticipate critical decisions, and guide and support the patient and family through the process. In order to assess patient and family coping, and identify individual strengths and community resources a social worker is essential to the team. In addition, they are also most adept to evaluating and negotiating financial and insurance resources. Pastoral care can be invaluable in helping to understand the patient’s spiritual strengths and concerns, and assist the patient and family in maintaining/reframing hope and establish meaning in the setting of advanced disease.

A key element of interdisciplinary palliative care is a strong emphasis on coordination of care. This is most commonly achieved through team meetings, where different disciplines verbally communicate each of their assessments in order to synthesize a comprehensive care plan that will meet the patient and family needs. For an IDT to be most effective, candid communication between team members is vital.

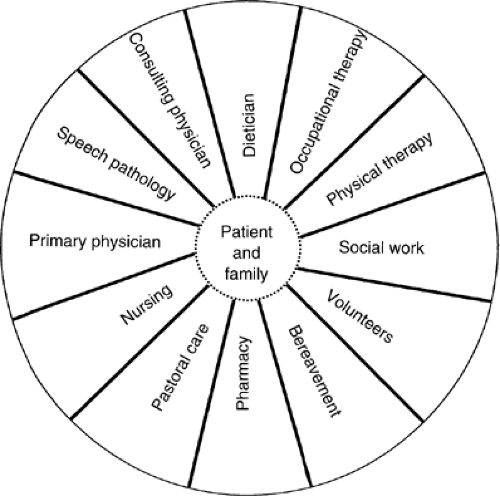

The distinction between interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary practice is critical. In the traditional multidisciplinary team, care of the patient is directed by the physician (Fig. 46.1). Many other members of the health care team may be involved in the delivery of care; however, efforts are often uncoordinated and fragmented.

The primary mode of communication between disciplines is the medical chart (25). The result is often ineffective communication between professions, lack of accountability, and a tendency for each discipline to independently develop their own patient care goals. To contrast, in an interdisciplinary model, leadership is shared and communication between team members is collaborative (13).

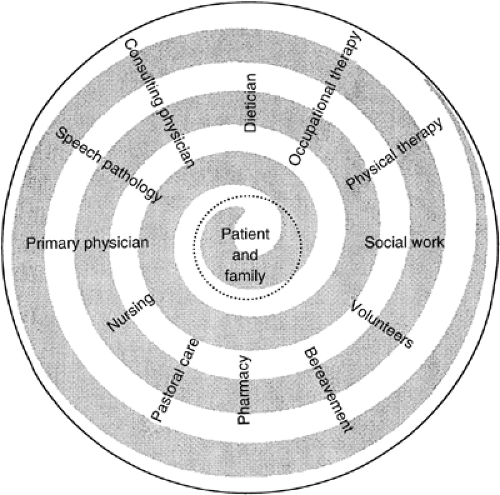

Although individual health care providers may have discipline-specific goals as part of the plan of care, it is

essential that the team remains focused on the patient-driven goals; communication between team members will be more effective if the focus of team interaction remains on the patient and family. Maintaining this focus is more successful when the team allows time to discuss the challenges individual professionals are facing in association with the patient and family, and if the team regularly reviews the plan of care. This model allows for team members to directly interact with the patient and family, and to provide consultation to one another, in order to achieve the goals identified by the patient and family (Fig. 46.2). Therefore, the sum (from the patient’s point of view) is greater than the individual parts (16,17).

essential that the team remains focused on the patient-driven goals; communication between team members will be more effective if the focus of team interaction remains on the patient and family. Maintaining this focus is more successful when the team allows time to discuss the challenges individual professionals are facing in association with the patient and family, and if the team regularly reviews the plan of care. This model allows for team members to directly interact with the patient and family, and to provide consultation to one another, in order to achieve the goals identified by the patient and family (Fig. 46.2). Therefore, the sum (from the patient’s point of view) is greater than the individual parts (16,17).

Interdisciplinary Communication and Collaboration

The most elegant of assessment will not benefit the patient, the family, or the IDT unless the information is communicated to all that need to know. Collaborative communication has been defined as working together cooperatively, sharing responsibility for problem solving, conflict management, decision making, communication and coordination (14). Open communication is linked with positive attitudes toward work, increased job satisfaction, increased job performance, increased job retention (15), decreasing cost of care (16). However, clinicians receive little education about how to effectively communicate with each other (21).

We communicate to team members what we feel is important. Physicians and nurses often use knowledge from the biomedical model of health and illness in assessment (18), and social workers often use the biopsychosocial-spiritual perspective (19). Nurses’ communication is narrative and descriptive, whereas the physicians’ communication is problem or need focused (17). Interruptions and distractions can negatively affect the process and contribute to clinicians forgetting to share pertinent information (17). There may be so much information that it is difficult to determine what is critical (17). Deficient communication creates conditions for acrimony, frustration, distrust, and can lead to inferior care and increased risk of error (20). Issues that impede effective communication include multiple service providers and a lack of standardized documentation (21).

Nursing and physician communication has been studied more than other interactions between the members of the IDT. Physicians state that they recognize the importance of nursing knowledge, but do not necessarily make use of it (18). Nurses complain that there is not enough information and physicians complain that there is too much information (21). Different disciplines require and use different information to provide optimal care (25).

The patient record serves as the most consistent source of patient specific health care data. It is where numerous clinicians go to find valid and reliable information. It also serves as the legal record for patient care (17). Verbal communication is less structured than written, but may be the primary way that information is transmitted (17). When choosing what to communicate, the situation, background, assessment, recommendations (SBAR) model may be used. Communicating information using this model provides the following:

Information about the patient’s current situation

A context for the patient’s current situation

An assessment of the current problem

A recommendation that addresses the patient’s needs

In addition to what is said, how it is said impacts collaboration. Verbal communication styles are important, and studies show that health care can be improved by using an attentive style of communication. These desired behaviors are not new and can be taught. It is recommended to avoid a contentious style, which is argumentative and challenging or a dominant style, which doesn’t allow others to participate (16). Descriptions of some of the communication styles are presented in Table 46.2.

Table 46.2 Communication Styles | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The IDT may be comprised of members of different generations. The Silent Generation was born between 1922 and 1942, the Baby Boomers were born between 1943 and 1960, Generation X was born between 1961 and 1980, and Generation Y was born in 1981 and later. Communication styles between generations may be different. If your team communicates using an electronic medical record, members of the Silent Generation and Baby Boomers may need more training and a different type of training than Generations X and Y (22). Health care professionals can anticipate that computers and related technology will become essential as a vital communication tool (27).

Tips to improve communication are not unique to end-of-life care. Table 46.3 can be seen for specific recommendations. Members of the IDT share the same goal of providing excellent care. Our challenge is to make the most of all interactions, utilizing the best knowledge and abilities of all team members that lead to positive patient outcomes (28)

Components of a Multidimensional Patient Assessment

There are a number of sources describing elements of a multidimensional patient assessment (2).

History of Illness and Treatment Responses

The initial elements of the MDPA parallel that of the traditional medical model. The assessment begins with an illness history that begins with determination of the primary

diagnosis and course of treatment. In addition, attention should be paid to assessing the therapies that have been utilized and not only their impact on the disease, but also their impact on the patient’s symptoms from the disease, and what therapies have exacerbated or ameliorated these symptoms (28). One must also elicit information about other illnesses and therapies that the patient has that may be important contributors to suffering and complicate subsequent therapies. One should have information on the extent/stage of disease, and familiarity with the diagnostic testing that confirmed the extent of disease.

diagnosis and course of treatment. In addition, attention should be paid to assessing the therapies that have been utilized and not only their impact on the disease, but also their impact on the patient’s symptoms from the disease, and what therapies have exacerbated or ameliorated these symptoms (28). One must also elicit information about other illnesses and therapies that the patient has that may be important contributors to suffering and complicate subsequent therapies. One should have information on the extent/stage of disease, and familiarity with the diagnostic testing that confirmed the extent of disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree