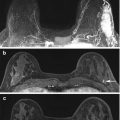

Fig. 3.1

High risk family history patient with normal mammograms. A suspicious 10 mm well-circumscribed rounded enhancing mass in the right upper inner quadrant on post-contrast subtraction images (white arrow) (a) with a morphological correlate on T2 (white arrow) (b). Histology confirms grade 2 invasive ductal carcinoma

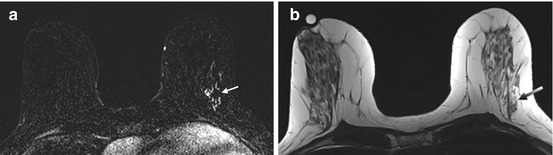

Fig. 3.2

BRCA1 positive patient with normal mammograms. An indeterminate area of segmental stippled enhancement in the lateral aspect of the left breast on post-contrast subtraction images (white arrow) (a) with no morphological correlate on T2 (gray arrow) (b). Histology confirms high-grade DCIS

The MRI report should include a management plan. This should indicate if a MR-directed ultrasound +/− biopsy is required and whether an MRI biopsy would be feasible if the ultrasound is normal. The lesions that do raise concern are a new mass lesion ≥5 mm or new isolated area of enhancement ≥10 mm in breasts which otherwise demonstrate minimal enhancement [39]. Careful directed ultrasound will identify about 60 % of these lesions, particularly if there is a mass. Lesions not seen on ultrasound should have an MRI biopsy with clip placement. Facilities that perform MRI should be able to perform MRI biopsy or have an established pattern of referral to a site that can perform these procedures.

3.6 Limitations of MRI Screening

MRI is more expensive and less readily available in comparison to mammography and ultrasound. It also requires the use of an intravenous gadolinium-based contrast agent that may not be suitable for patients with renal disease. MRI may not be feasible for certain women such as those with pacemakers, aneurysm clips or claustrophobia [44]. It is important that patients are appropriately counselled and aware of the methods and frequency of screening investigations, benefits and risks including the possibility of false-positive and false-negative studies with the development of interval cancers.

The increased sensitivity of screening with MRI should be considered with evidence suggesting a 3–5 fold higher risk of patient recall for investigation of false-positive results [45]. Biopsies that do not yield malignancy are considered false-positive results and a disadvantage of MRI screening as this generates unnecessary patient anxiety and has its associated costs in time and money. In the UK MARIBS study, the recall rate was 3.9 % for mammography and 10.7 % for MRI with an overall recall rate of 12.7 % combining both techniques. Overall, there were 8.5 recalls and 0.21 benign surgical biopsies per cancer detected. Therefore, although the absolute recall rate is high, taking into account the high annual risk of cancer in this group at high familial risk, the recall and intervention rate per cancer detected are similar to that found in screening the normal population [46].

In the United States, a multicentre study prospectively evaluated the biopsy rates, positive predictive value and cancer yield of screening mammography, ultrasound and MRI in asymptomatic women who were identified as genetically at high risk including BRCA1/2 carriers or women with at least a 20 % probability of carrying the gene [47]. Findings on MRI prompted biopsy in 8.2 %, while mammography and ultrasound prompted biopsy in 2.3 % of patients. The positive predictive value of biopsies performed as a result of MRI was 43 % with a diagnostic yield of 3.5 % in comparison to 1.2 % for mammography and 0.6 % for ultrasound. This study demonstrated that although screening MRI had a higher biopsy rate, it did help to detect more cancers than either mammography or ultrasound. This suggests that MRI is potentially cost-effective for screening younger women at very high risk of breast cancer, but less cost-effective for screening populations with a wider risk or wider age distribution.

False-negative results can occur when the MRI is reported as normal and fails to diagnose a cancer that is already present. This may be due to a suboptimal study causing difficulties in interpretation due to inadequate contrast agent administration, poor fat suppression or movement artefact. Lesion size and location can also affect accuracy of interpretation with difficulties arising when the abnormality is small (<5 mm) or if the lesion is located close to the boundary of the field of view [48]. In some cases, the lesion may be missed or misinterpreted by the reader [49].

3.7 Conclusion

Standardised high quality MRI examinations achieving a high sensitivity, in addition to available evidence of the efficacy of MRI screening, have allowed expert opinion to support MRI as a screening test in higher risk women who have been appropriately assessed in a specialist clinic. It is different from mammographic screening where the stronger evidence allows it to be applied to a whole population. Women who are choosing between risk-reducing mastectomy and screening should be counselled that although the sensitivity of MRI in combination with mammography is excellent, it will always be less than 100 %. In addition, some very small tumours will already be incurable at the time of detection. Women who opt for screening should be willing to accept the risk of a false negative result as well as the extra investigations generated by a false positive examination. Ideally in the future, personalised screening based on accurate risk assessment and the increased availability and speed of gene testing in specialised family history clinics will facilitate the development of a tailored screening programme. This may require more intensive screening strategies in some younger women, although the cost benefit of this in terms of increased surveillance, recalls for further work-up and economics would have to be considered.

References

1.

Prevalence and penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population-based series of breast cancer cases. Anglian Breast Cancer Study Group. Br J Cancer. 2000;83(10):1301–8.

2.

3.

Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, Narod S, Goldgar D, Devilee P, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(3):676–89.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

4.

Evans DG, Shenton A, Woodward E, Lalloo F, Howell A, Maher ER. Penetrance estimates for BRCA1 and BRCA2 based on genetic testing in a clinical cancer genetics service setting: risks of breast/ovarian cancer quoted should reflect the cancer burden in the family. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:155.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Irwig L, Houssami N, Armstrong B, Glasziou P. Evaluating new screening tests for breast cancer. BMJ. 2006;332(7543):678–9.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

10.

Banks E, Reeves G, Beral V, Bull D, Crossley B, Simmonds M, et al. Influence of personal characteristics of individual women on sensitivity and specificity of mammography in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 2004;329(7464):477.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree